Rewarding University Professors: a Performance-Based Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition of Facutly and Types of Appointments

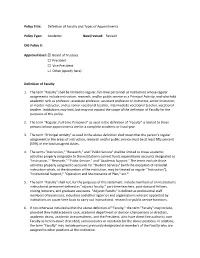

Policy Title: Definition of Faculty and Types of Appointments Policy Type: Academic New/revised: Revised Old Policy #: Approval level: ☒ Board of Trustees ☐ President ☐ Vice President ☐ Other (specify here) Definition of Faculty 1. The term "Faculty" shall be limited to regular, full-time personnel at institutions whose regular assignments include instruction, research, and/or public service as a Principal Activity, and who hold academic rank as professor, associate professor, assistant professor or instructor, senior instructor, or master instructor, and as senior vocational teacher, intermediate vocational teacher, vocational teacher. Institutions may limit, but may not expand the scope of the definition of Faculty for the purposes of this policy. 2. The term "Regular, Full-time Personnel" as used in the definition of "Faculty" is limited to those persons whose appointments are for a complete academic or fiscal year. 3. The term "Principal Activity" as used in the above definition shall mean that the person's regular assignment in the areas of instruction, research and/or public service must be at least fifty percent (50%) of the total assigned duties. 4. The terms "Instruction," "Research," and "Public Service" shall be limited to those academic activities properly assignable to the institution's current funds expenditures accounts designated as "Instruction," "Research," "Public Service," and "Academic Support." The terms exclude those activities properly assigned to accounts for "Student Services" (with the exception of remedial instruction which, at the discretion of the institution, may be treated as regular "Instruction"), "Institutional Support," "Operation and Maintenance of Plan," etc.* 5. The term "Faculty" shall not, for the purposes of this statement, include members of an institution's instructional personnel defined as "adjunct faculty," part-time teachers, post-doctoral fellows, visiting lecturers, and graduate assistants. -

Managing Academic Staff in Changing University Systems: International Trends and Comparisons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 586 HE 032 364 AUTHOR Farnham, David, Ed. TITLE Managing Academic Staff in Changing University Systems: International Trends and Comparisons. INSTITUTION Society for Research into Higher Education, Ltd., London (England). ISBN ISBN-0-335-19961-5 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 376p. AVAILABLE FROM Open University Press, 325 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106. Web site: <http://www.openup.co.uk>. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Faculty; Cross Cultural Studies; *Educational Administration; *Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; *Higher Education; Human Resources; Legislation; Public Policy; Teacher Salaries; Teaching (Occupation); Universities ABSTRACT This collection of 17 essays focuses on how faculty are employed, rewarded, and managed at universities in developed and developing nations. The essays, which include an introduction, 10 essays discussing European practices, two that focus on Canada and the United States, three which focus on Australia, Japan, and Malaysia, and a concluding chapter are: (1)"Managing Universities and Regulating Academic Labour Markets" (David Farnham); (2) "Belgium: Diverging Professions in Twin Communities" (Jef C. Verhoeven and Ilse Beuselinck); (3) "Finland: Searching for Performance and Flexibility" (Turo Virtanen); (4) "France: A Centrally-Driven Profession" (June Burnham); (5) "Germany: A Dual Academy" (Tassilo Herrschel); (6) "Ireland: A Two-Tier Structure" (Thomas N. Garavan, Patrick Gunnigle, and Michael Morley); (7) "Italy: A Corporation Controlling a System in Collapse" (William Brierley); (8) "The Netherlands: Reshaping the Employment Relationship" (Egbert de Weert); (9) "Spain: Old Elite or New Meritocracy?" (Salavador Parrado-Diez); (10) "Sweden: Professional Diversity in an Egalitarian System" (Berit Askling); (11) "The United Kingdom: End of the Donnish Dominion?" (David Farnham); (12) "Canada: Neo-Conservative Challenges to Faculty and Their Unions" (Donald C. -

Curriculum Vitae

Laurent SALOFF-COSTE November 2019 Curriculum vitae Born April 16, 1958 in Paris, France. Education 1976 Baccalaur´eatC, Paris. 1976-78 Math´ematiquessup´erieureset sp´eciales,Paris. 1978-80 Ma^ıtrisede Math´ematiquesPures, Universit´eParis VI. 1981 Agr´egationde Math´ematiques. 1983 Th`esede 3`emecycle supervised by N. Varopoulos, Universit´eParis VI: \Op´erateurspseudo-diff´erentiels sur un corps local". 1989 Doctorat d'Etat,´ Universit´eParis VI: \Analyse harmonique et analyse r´eellesur les groupes". Academic Positions 1981-85 Professeur agr´eg´e(High school teacher). 1985-88 Professeur agr´eg´eat Universit´eParis VI (Lecturer). 1988-1993 Charg´ede recherche, C.N.R.S., at Universit´eParis VI. 1990-91 Visiting scholar, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, joint fellowship from N.S.F. and C.N.R.S.. 1993-2005 Directeur de recherche, C.N.R.S., at Universit´ePaul Sabatier, Toulouse, France. 1998| Professor of Mathematics, Cornell University, NY, USA. 2009-2015 Chair, Department of Mathematics, Cornell University, NY, USA. 2017| Abram R. Bullis Professor of Mathematics, Cornell University, NY, USA. Awards and distinctions Rollo Davidson Award, 1994 Guggenheim Fellow, 2006-07 Fellow of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics (2011) Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2011) Fellow of the American Mathematical Society (2012-inaugural class) 1 External funding 1995{1997 Principal investigator, NATO Collaborative Research Grant 950686 ($8000), Analysis and Geometry of Finite Markov Chains (with Persi Diaconis). 1997{1998 Renewal of Nato Collaborative Research Grant 950686 ($5500) 1999-2001 NSF Grant DMS-9802855, Analysis and geometry of certain Markov chains and processes. 2001-2006 NSF Grant DMS-0102126, Analysis and geometry of Markov chains and diffusion processes. -

Academic Careers and the Valuation of Academics. a Discursive

High Educ DOI 10.1007/s10734-017-0117-1 Academic careers and the valuation of academics. A discursive perspective on status categories and academic salaries in France as compared to the U.S., Germany and Great Britain Johannes Angermuller1,2 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Academic careers are social processes which involve many members of large populations over long periods of time. This paper outlines a discursive perspective which looks into how academics are categorized in academic systems. From a discursive view, academic careers are organized by categories which can define who academics are (subjectivation) and what they are worth (valuation). The question of this paper is what institutional categorizations such as status and salaries can tell us about academic subject positions and their valuation. By comparing formal status systems and salary scales in France with those in the U.S., Great Britain and Germany, this paper reveals the constraints of institutional categorization systems on academic careers. Special attention is given to the French system of status categories which is relatively homogeneous and restricts the competitive valuation of academics between institutions. The comparison shows that academic systems such as the U.S. which are charac- terized by a high level of heterogeneity typically present more negotiation opportunities for the valuation of academics. From a discursive perspective, institutional categories, therefore, can reflect the ways in which academics are valuated in the inter-institutional job market, by national bureaucracies or in professional oligarchies. Keywords Academic status . Social categories .Academic careers in Germany.France .UK and U. -

Insights from a Survey-Based Analysis of the Academic Job Market

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/796466; this version posted October 9, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Insights from a survey-based analysis of the academic job market Jason D. Fernandes1†, Sarvenaz Sarabipour2†, Christopher T. Smith3, Natalie M. Niemi4, Nafisa M. Jadavji5, Ariangela J. Kozik6, Alex S. Holehouse7, Vikas Pejaver8, Orsolya Symmons9, Alexandre W. Bisson Filho10, Amanda Haage11* 1Department of Biomolecular Engineering, University of California, Santa Cruz, California, United States 2Institute for Computational Medicine & Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States 3Office of Postdoctoral Affairs, North Carolina State University Graduate School, Raleigh, North Carolina, United States 4Morgridge Institute for Research, Madison, Wisconsin, United States; Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States 5Department of Biomedical Sciences, Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona, United States 6Division of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States 7Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biophysics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, United States 8Department of Biomedical Informatics & Medical -

Industry Vs. Academic Research Positions

Academia vs Industry: Choose Your Own Adventure A.J. Brush, Microsoft Lisa Wu Wills, Duke University Thanks to previous presenters of this topic! A.J. Brush Education: • University of Washington, Ph.D. 2002 • Williams College, BA 1996 Career • Microsoft: Microsoft Research for 12 years, 4 years on Cortana product • Research areas: HCI, Ubicomp, Family and Fun • Kids: Colin (19), Ryan (16) • Hobbies: Exercise, Reading, Travel Lisa Wu Wills Education • Columbia University, Ph.D. 2014 • University of Michigan Ann Arbor, M.S. • University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, B.S. Career (reverse chronologically) • Assistant Professor at Duke University, Postdoctoral Researcher @ UC Berkeley, Researcher @Intel Labs, back to school for Ph.D., Computer Architect @Intel (Xeon Phi, Knights product line) • Research areas: Computer Architecture, HardWare Accelerators, Big Data Analytics, Healthcare Fun • Travel, Art Museums, Performance Arts, Cooking, Beach A vs. B: So Simple, Right? Academia Industry/Government/Lab could be: could be: • Engineer • Professor at a research- • Research manager oriented school teaching- oriented school • Research Scientist • Technical or Managerial • Research associate Leadership Academic administration • Consulting • Start-up All Choices are Valid! • Do what you love • If you don’t love what you’re doing, do something else • A Ph.D. gives you that option • Take ownership of what you do now and what you want to do next (your career is what you make of it) Aspire to be happy - not ‘stereotypical' What is Important to You? -

The Status of Higher Education Teaching Personnel in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States

The Status of Higher Education Teaching Personnel in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States Report Prepared for Education International by David Robinson Associate Executive Director Canadian Association of University Teachers March 2006 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ii 1. Summary and Overview 1 2. Australia 14 3. Canada 26 4. New Zealand 36 5. United Kingdom 44 6. United States 52 i Acknowledgements The following people provided valuable assistance for this project: Lindsay Albert, Verda Cook, Rex Costanza, Stephen Court, John Curtis, Darrell Drury, Larry Dufay, Larry Gold, John Hollingsworth, Helen Kelly, Jay Kubler, Andrew Nette, and Craig Smith. Any errors or omissions, however, are solely the responsibility of the author. ii 1. Summary and Overview This study examines recent trends in the salaries, working conditions, and rights of academic staff in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It begins by providing a summary and overview of some of the major trends across the nations under study. This is followed by more detailed analyses of the status of faculty in each country. The main findings of the study include the following: In most countries, public funding for higher education has declined sharply over the past decade. While modest increases in spending are now being recorded in several countries, higher education institutions are nevertheless more dependent today upon private financing than at any time in the recent past. Such funding comes primarily in the form of tuition fees and private research contracts. Increased accountability and performance assessments are subjecting academic staff to more and more intrusive bureaucratic control and oversight. -

Handbook of Academic Titles

Handbook of Academic Titles by Michael I. Shamos, Ph.D., J.D. Distinguished Career Professor School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Visiting Professor, The University of Hong Kong [email protected] There are over 3,300 accredited colleges and universities in the United States. These institutions have conferred on their academic faculties and staff a bewildering array of titles and designations. The titles can be confusing and their significance is often misunderstood. Some titles imply that the holder has tenure, while others do not. Some suggest a concentration in research rather than teaching, while others convey that the incumbent is primarily engaged in activities outside of an academic institution. In addition, a menagerie of prefixes and modifiers are used to indicate rank and other status information. Adding to the complexity of the problem is the fact that the same title may have different meanings at different institutions. The purpose of this handbook is to provide a thorough glossary explaining the significance of most titles in use in the United States today. Copyright © 2011 Michael I. Shamos Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 Academic Titles and Related Terminology ............................................................ 5 Title Prefixes and Suffixes ................................................................................ 176 Faculties .......................................................................................................... -

WJC Standards and Procedures for Faculty Rank (Rev. May 27, 2021)

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION____________________________________________________________ 3 PREAMBLE ________________________________________________________________ 3 DEFINING SCHOLARSHIP AT WILLIAM JAMES COLLEGE ___________________ 4 Instructor ________________________________________________________________ 5 Senior Instructor __________________________________________________________ 5 Assistant Professor ________________________________________________________ 5 Associate Professor ________________________________________________________ 6 Professor of Practice _______________________________________________________ 7 Professor ________________________________________________________________ 8 Adjunct Faculty ______________________________________________________________ 9 Lecturer _________________________________________________________________ 9 Senior Lecturer ___________________________________________________________ 9 Clinical Faculty ______________________________________________________________ 9 Clinical Instructor _________________________________________________________ 9 Senior Clinical Instructor____________________________________________________ 9 Faculty Emeriti/ae ___________________________________________________________ 10 Visiting Scholar _____________________________________________________________ 10 CRITERIA FOR APPOINTMENT AND PROMOTION __________________________ 10 Steps for Creating a Promotions Profile _________________________________________ 10 Areas of Excellence _______________________________________________________ -

Fact Sheet 2019

FACT SHEET 2019 OVERVIEW UW APS 40.1 defines academic personnel as faculty, librarians, residents and fellows, postdoctoral scholars, and academic staff. This Fact Sheet, created annually by the Office of Academic Personnel (OAP), focuses on data about tenure, without tenure by reason of funding, and research professorial tracks, and full-time, promotion-eligible lecturer titles. In addition the international scholars data represents all individuals on OAP-sponsored J-1 or H-1B visas. Overall, the data in this report represents the population as of October 31, 2019. For digital versions of this report and others, visit ap.washington.edu. FACULTY STATISTICS BY RANK AND TITLE American Pacific Multiple Declined Did Not Total Female Male Asian Black Hispanic White Indian Islander Race to Disclose Participate Professorial 4251 1791 2460 16 727 89 193 4 2826 67 55 274 Professor 1841 625 1216 3 245 26 55 1 1419 19 10 63 Associate Professor 1348 602 746 7 247 32 71 1 854 30 20 86 Assistant Professor 1062 564 498 6 235 31 67 2 553 18 25 125 Instructional 473 274 199 1 55 8 25 0 343 11 10 20 Principal Lecturer 54 34 20 0 4 0 3 0 47 0 0 0 Senior Lecturer 230 130 100 0 30 5 13 0 166 8 3 5 Lecturer 189 110 79 1 21 3 9 0 130 3 7 15 Total 4724 2065 2659 17 782 97 218 4 3169 78 65 294 PROFESSORIAL TRACK BY RANK INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON OAP-SPONSORED VISAS Tenure WOT Research ChinaChina SouthSout hKorea Korea Professorial Faculty 2114 1866 271 IndiaIndia Professor 1114 635 92 JapanJapan Scholars by Visa Associate Professor 586 667 95 CanadaCanada H-1 -

Tenure and Pay Structures in Canadian Universities. Research Monographs in Higher Education, Number 4

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 317 HE 032 887 AUTHOR Hum, Derek TITLE Tenure and Pay Structures in Canadian Universities. Research Monographs in Higher Education, Number 4. INSTITUTION Manitoba Univ., Winnipeg. Centre for Higher Education Research and Development. ISBN ISBN-1-896732-20-8 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 95p. AVAILABLE FROM Centre for Higher Education Research and Development, University of Manitoba, 220 Sinnott Building, 70 Dysart Road, Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3T 2N2. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Career Ladders; College Faculty; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Incentives; Institutional Administration; Personnel Selection; Promotion (Occupational); Student Motivation; Teacher Employment Benefits; *Teacher Salaries; *Tenure; Tenured Faculty; Unions IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Germany ABSTRACT This monograph examines tenure and pay structures in Canadian universities, focusing on hiring, tenure, promotion, salaries, and termination; and examining the employment relationship from both economic and managerial perspectives. After briefly reviewing the concept of tenure, the discussion moves to career hierarchies and pay structures, including career ladders (hiring, tenure, and promotion), and wage structures (underpayment and overpayment of professors), which are examined from an employment contract perspective. The next sections focus on unique features of tenure (e.g., why so many candidates are hired for a single competitive tenure position or why those denied tenure must be asked to leave) and propose several alternative routes to tenure. Other topics considered are whether standards differ for universities with a more egalitarian philosophy, and the rationale for tenure as a way of protecting faculty. A brief section looks outside the Canadian system to examine the German system of hiring professors. -

The Gender Dimension the Expert Panel on Women in University Research

STRENGTHENING CANADA’S RESEARCH CAPACITY: THE GENDER DIMENSION The Expert Panel on Women in University Research Science Advice in the Public Interest STRENGTHENING CANADA’S RESEARCH CAPACITY: THE GENDER DIMENSION The Expert Panel on Women in University Research ii Strengthening Canada’s Research Capacity: The Gender Dimension THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Suite 1401, Ottawa, ON Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Governors of the Council of Canadian Academies. Board members are drawn from the Royal Society of Canada (RSC), the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE), and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the Council for their special competencies and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from the Minister of Industry. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, the Expert Panel on Women in University Research, and do not necessarily represent the views of their organizations of affiliation or employment. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Strengthening Canada's research capacity [electronic resource] : the gender dimension / The Expert Panel on Women in University Research. Issued also in French under title: Renforcer la capacité de recherche au Canada. Includes bibliographical references and index. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Issued also in print format. ISBN 978-1-926558-50-9 1.