179 CHAPTER 7 HIGH RISE and ITS OPPONENTS High Rise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Program Choices

MY PROGRAM CHOICES Term 1: 4th January to 27th March 2021 Name: ______________________________________ DSA Community Solutions site: Taren Point Thank you for choosing to purchase a place in one of our quality programs. We offer a variety of group based and individualised programs in our centre and community locations. There are four terms per year. You will have the opportunity to make a new program selection each term. To change your program choices or to make a new program selection within the term, please contact your Service Manager. Here is a summary of the programs you can select, including costs, program locations, what you need to wear or bring with you each day. To secure a place in your chosen program, please submit this signed form at the earliest. These are the DSA Programs I choose to participate in. Live Signature: ______________________________ life the way you choose For more information call Georgina Campbell, Service Manager on 0490 305 390 1300 372 121 [email protected] www.dsa.org.au Time Activity Cost Yes Mondays All day* Manly Ferry Opal Card Morning Bowling at Mascot $7 per week Pet Therapy @ the Centre $10 per week Afternoon CrossFit Gym Class $10 per week Floral arrangement class $7 per week Tuesdays All day* Laser Tag/Bowling @ Fox Studios $8-week/Opal card Morning Beach fitness @ Wanda No cost Tennis at Sylvania Waters $5 Afternoon The Weeklies music practice at the Centre No cost Art/Theatre Workshop @ the Centre $20 per week Wednesdays All day* Swimming & Water Park @ Sutherland Leisure Centre $7 per week Morning Flip Out @ Taren Point $10 per week Cook for my family (bring Tupperware container) $10 per week Afternoon Basketball @ Wanda No cost Disco @ the Centre No cost • All full day programs start and finish at Primal Joe’s Cafe near Cronulla Train station, and all travel is by public trans- port. -

Peter Hooper 15 Cremorne Road CREMORNE POINT NSW 2090 D365/19 AB7 (CIS)

Original signed by Robyn Pearson on 9/3/2020 Date determined: 6/3/2020 Date operates: 9/3/2020 Date lapses: 9/3/2025 Peter Hooper 15 Cremorne Road CREMORNE POINT NSW 2090 D365/19 AB7 (CIS) ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND ASSESSMENT ACT, 1979 AS AMENDED NOTICE OF DETERMINATION – Approval Development Application Number: 365/19 15 Cremorne Road, Cremorne Point Land to which this applies: Lot No.: 32, DP: 4389 Applicant: Peter Hooper Proposal: Alterations and additions to a dwelling. Subject to the provisions of Section 4.17 of the Determination of Development Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, Application: approval has been granted subject to conditions in the notice of determination. Date of Determination: 6 March 2020 The development application has been assessed against the relevant planning instruments and policies, in particular the North Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2013 and the North Sydney Development Control Plan 2013, and generally found to be satisfactory. There would be no unreasonable overshadowing, view loss, privacy loss and/or excessive bulk and scale as a Reason for approval: result of the proposal given that the works, subject to conditions to retain significant fabric and reduce glazing, are mostly sympathetic with the character of the heritage item. While the works to move the kitchen to the eastern room will necessitate alterations to primary rooms and some loss of original internal fabric, the works, however are considered acceptable on balance given that the significance of the heritage item primarily lies in fabric unaffected by these changes. RE: 15 CREMORNE ROAD, CREMORNE POINT DEVELOPMENT CONSENT NO. 365/19 Page 2 of 25 It is considered that the works to enhance resident amenity would only have minimal intrusive impact on the heritage item known as ‘Toxteth’, with the significant internal and external original fabric substantially intact, subject to conditions. -

2019–20 Waverley Council Annual Report

WAVERLEY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2019–20 Waverley Council 3 CONTENTS Preface 04 Part 3: Meeting our Additional Mayor's Message 05 Statutory Requirements 96 General Manager's Message 07 Amount of rates and charges written off during the year 97 Our Response to COVID-19 and its impact on the Operational Plan and Budget 09 Mayoral and Councillor fees, expenses and facilities 97 Part 1: Waverley Council Overview 11 Councillor induction training and Our Community Vision 12 ongoing professional development 98 Our Local Government Area (LGA) Map 13 General Manager and Senior Waverley - Our Local Government Area 14 Staff Remuneration 98 The Elected Council 16 Overseas visit by Council staff 98 Advisory Committees 17 Report on Infrastructure Assets 99 Our Mayor and Councillors 18 Government Information Our Organisation 22 (Public Access) 102 Our Planning Framework 23 Public Interest Disclosures 105 External bodies exercising Compliance with the Companion Waverley Council functions 25 Animals Act and Regulation 106 Partnerships and Cooperation 26 Amount incurred in legal proceedings 107 Our Financial Snapshot 27 Progress against Equal Employment Performance Ratios 29 Opportunity (EEO) Management Plan 111 Awards received 33 Progress report - Disability Grants and Donations awarded 34 Inclusion Action Plan 2019–20 118 Grants received 38 Swimming pool inspections 127 Sponsorships received 39 Works undertaken on private land 127 Recovery and threat abatement plans 127 Part 2: Delivery Program Environmental Upgrade Agreements 127 Achievements 40 Voluntary -

BE Prizes 2009.Xlsx

UNSW Built Environment Prizes 2009 The UNSW Built Environment is grateful for the generous support of the members of our diverse community who share their passion for both the design professions and education by creating prizes which acknowledge the outstanding work of our students each year. The recipients will be presented with their prize and certificate, by representatives of the donors of the prize, at an event to be held later in 2010. UNSW Built Environment Prize Name Winner 2009 Amount Reason for Prize Prize Description The Dean’s List was established to celebrate the academic achievements of our high performing undergraduate For the highest weighted students. Every semester, undergraduate students who Matthew Ritson average mark amongst all have achieved a Weighted Average Mark of 80 over in The Dean's Award $250 Shawna NG undergraduate programs in that semester (and undertaken at least 18 Units of Credit) each semester ‐ one and two are placed on the Dean’s List. Additionally, the student with the highest WAM for each semester is awarded the Dean’s Award. Architecture Prize Name Winner 2009 Amount Reason for Prize Prize Description Morton Herman (1907‐1983) architect, architectural historian and architectural conservationist lectured primarily in architectural history from 1945 until the late For the best performance in 1960s. He received the award of Member of the Order of The Morton Herman Memorial Alexander Redzic Studies of Historic Structures $500 Australia in 1979 being referred to as the 'father of Prize Isaac Williams in the Bachelor of architectural history and conservation in this country'. Architectural Studies Program This prize was established by Philip Cox AO who made a significant contribution to Herman's welfare towards the end of his life. -

Cremorne Point Flyer

What makes Cremorne Point Significant? - Location Map find out a little about the Point’s wonderful architecture and why the area has been designated as a conservation area by the Council.* Who Cares For The Bush? - what is Bushcare? See what local residents have been able to achieve. Learn about bush regeneration and how to become involved. * For further information on the Point’s architectural features pick up a North Sydney Heritage Leaflet (No. 29) entitled The Heart of Cremorne Point from the Stanton Library or by Cremorne phoning the Library on 9936 8400. Point Access by Public Transport Ferry from Circular Quay Wharf No. 4 to Cremorne Point Wharf. Bus from either Foreshore Wynyard or Northern Beaches Line, change buses at Neutral Bay Junction and catch the Cremorne Wharf bus No. 225 at Hayes and Walk Lower Wycombe Streets, Neutral Bay. Access by Private Transport Turn off the main thoroughfare, Military Road, into Murdoch Street and then directly into Cremorne Reserve is a foreshore reserve Milson Road. Parking is limited. that stretches from Shell Cove, Toilets are located in the picnic area at the end of Cremorne around to Mosman Bay. the Point, not far from the main trackhead sign. It offers an amazing diversity of natural For further enquiries please contact the Bushcare Officer on 9936 8252. and historical features along with unrivalled views of Sydney Harbour. Illustration Acknowledgement: Mo Orkiszewski Cremorne Point Foreshore Walk The Story of Cremorne Point North Sydney Council and the Department of Start from Bogota Avenue Urban Affairs and Planning Greenspace A Wisp of Sydney Sandstone Bushland - an Program have developed an interpretive self insight to the local native fauna and flora of guided walking tour that allows you to delve into Cremorne Point. -

North Shore Houses Project

NORTH SHORE HOUSES, State Library of New South Wales Generously supported by the Upper North Architects Network (SPUN), Australian Institute of Architects. Compiled by John Johnson Arranged alphabetically by architect. Augustus Aley Allen & Jack Architects (Russell Jack) Allen, Jack & Cottier (Russell Jack) Sydney Ancher Adrian Ashton Arthur Baldwinson Arthur Baldwinson (Baldwinson & Booth) John Brogan Hugh Buhrich Neville Gruzman Albert Hanson Edward Jeaffreson Jackson Richard Leplastrier Gerard McDonnell D.T. Morrow and Gordon Glen Murcutt Nixon & Adam (John Shedden Adam) Pettit, Sevitt & Partners Exhibition Houses Ross Brothers (Herbert Ernest Ross and Colin John Ross) Ernest A Scott (Green & Scott) Harry Seidler Harry and Penelope Seidler Douglas Snelling John Sulman War Service Homes Commission Leslie Wilkinson Wilson & Neave (William Hardy Wilson) Architect: Augustus Aley ‘Villa Maria’ (House for Augustus Aley), 1920 8 Yosefa Avenue, Warrawee Architect Augustus Aley (1883-1968) built 4 houses in Yosefa Avenue, Warrawee (Nos. 7, 8, 9, 11) two of which were constructed for himself. He and wife Beatrice (1885?-1978) moved into Villa Maria in 1920 and developed a fine garden. In 1929 they moved to a new house, Santos, at 11 Yosefa Ave. “Mr Aley, the architect, and incidentally the owner, has planned both house and garden with the utmost care, so that each should combine to make a delightful whole. The irregular shape and sloping nature of the ground presented many difficulties, but at the same time abounded with possibilities, of which he has taken full advantage. The most important thing, in a house of this sort, and indeed in any house, is aspect, and here it is just right. -

Temporary Works Site: Anzac Park, Cammeray

Community Update July 2018 Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link Temporary works site: Anzac Park, Cammeray Warringah Road Frenchs Forest Western Harbour Tunnel Warringah Road Some minor works to improveFrenchs Forestreference design and there will and Beaches Link is a major drainage will be requiredForestville at be extensive community and transport infrastructure project Brookvale Anzac Park. stakeholderWakehurst Parkway engagement over that makes it easier, faster and the comingAllambie months. Heights The works will be relatively Forestvilleminor, safer to get around Sydney. We now want to hear what Brookvale short-term, and will be on the Wakehurst Parkway Killarney Heights you think about the proposed As Sydney continues to grow, our eastern side of the park, near the Allambie Heights transport challenge also increasesLindfield Warringah Freeway – away from reference design. and congestion impacts our Roseville the War Memorial and Anzac ParkKillarney Your Heights feedbackNorth will help us further economy. Public School. Balgowlah refine the design beforee we seek Castle Cove ridg B tion nt via r e Condamine St Lindfield u D While the NSW Government actively planning approval. B k e There will be minimal impacts to e r C manages Sydney’s daily traffic Middle Cove theRoseville park, and no impact to the ThereMiddle will be furtherNorth extensive Chatswood Harbour Balgowlah demands and major new public school, War Memorial or private community engagement once the Sydney Road Balgowlah e CastleCastlecrag Cove ridg transport initiatives are underway, B ation nt evi property. Environmental Impact Statementr D Condamine St u k B e it’s clear that even more must e r Lane Cove Tunnel is onSeaforth public display. -

The National Trust and the Heritage of Sydney Harbour Cameron Logan

The National Trust and the Heritage of Sydney Harbour cameron logan Campaigns to preserve the legacy of the past in Australian cities have been Cameron Logan is Senior Lecturer and particularly focused on the protection of natural landscapes and public open the Director of Heritage Conservation space. From campaigns to protect Perth’s Kings Park and the Green Bans of the in the Faculty of Architecture, Design Builders Labourers Federation in New South Wales to contemporary controversies and Planning at the University of such as the Perth waterfront redevelopment, Melbourne’s East West Link, and Sydney, 553 Wilkinson Building, G04, new development at Middle Harbour in Sydney’s Mosman, heritage activists have viewed the protection and restoration of ‘natural’ vistas, open spaces and ‘scenic University of Sydney, NSW 2006, landscapes’ as a vital part of the effort to preserve the historic identity of urban Australia. places. The protection of such landscapes has been a vital aspect of establishing Telephone: +61–2–8627–0306 a positive conception of the environment as a source of both urban and national Email: [email protected] identity. Drawing predominantly on the records of the National Trust of Australia (NSW), this paper examines the formation and early history of the Australian National Trust, in particular its efforts to preserve and restore the landscapes of Sydney Harbour. It then uses that history as a basis for examining the debate surrounding the landscape reconstruction project that forms part of Sydney’s KEY WORDS highly contested Barangaroo development. Landscape Heritage n recent decades there has been a steady professionalisation and specialisation History Iof heritage assessment, architectural conservation and heritage management Sydney as well as a gradual extension of government powers to regulate land use. -

Baden & Daniela Moore 82 Cremorne Road

Original signed by Robyn Pearson on 5/6/2019 Date determined: 5/6/2019 Deferred commencement Date: 5/6/2019 Date lapses: 5/6/2020 Baden & Daniela Moore 82 Cremorne Road CREMORNE POINT NSW 2090 D343/18 MS3 (CIS) ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND ASSESSMENT ACT, 1979 AS AMENDED NOTICE OF DETERMINATION – Deferred Commencement Issued under Section 4.18 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (“the Act”). Clause 100 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulation 2000 (“the Regulation”) Development Application Number: 343/18 82 Cremorne Road, Cremorne Point Land to which this applies: Lot No.: 1, DP: 913026 Applicant: Baden & Daniela Moore Partial demolition of existing dwelling house and garage, and construction of a three storey rear addition with two Proposal: vehicle garage, swimming pool and associated landscaping. The development application was considered by the North Sydney Local Planning Panel (NSLPP) on 5 Determination of Development June 2019. Subject to the provisions of Section 4.17 of Application: the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, “Deferred Commencement” consent has been granted, subject to the conditions in this notice of determination. Date of Determination: 5 June 2019 The Panel is satisfied that the height exceedance is acceptable in the circumstances subject to the Deferred Commencement Conditions (as amended) and does not result in any unreasonable environmental impacts including satisfying the principle of view sharing. The Panel notes that from a heritage point of view, the Reason for Deferred existing cottage and roof will be retained and the siting of Commencement: the dwelling requires any alterations and additions to be sited towards the laneway. -

Cremorne Point to Taronga Zoo

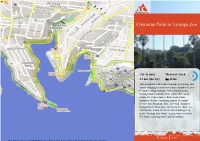

Cremorne Point to Taronga Zoo 1 hr 45 mins Moderate track 3 4.2 km One way 218m This delightful walk from Cremorne to Taronga Zoo enjoys stunning harbour views and a number of sites to explore along bushland and suburban tracks. Starting from Cremorne ferry wharf, there is an option for a closer look at Robertsons Point lighthouse before continuing around Cremorne Reserve into Mosmans Bay. The walk continues through Little Sirius Bay, and offers the chance to visit historic Camp Curlew before finishing at the scenic Taronga Zoo wharf. A great way to enjoy a few hours exploring this beautiful harbour. 44m 1m Cremorne Reserve Maps, text & images are copyright wildwalks.com | Thanks to OSM, NASA and others for data used to generate some map layers. Cremorne Point Ferry Wharf Before You walk Grade Cremorne Point Ferry Wharf marks the first stop on the Mosman Bushwalking is fun and a wonderful way to enjoy our natural places. This walk has been graded using the AS 2156.1-2001. The overall Ferry Service. The wharf is home to Sophie's Place cafe, serving Sometimes things go bad, with a bit of planning you can increase grade of the walk is dertermined by the highest classification along coffee, food and drinks. A public phone, public toilets and a your chance of having an ejoyable and safer walk. the whole track. children's playground can all be found within 100m of this wharf. Before setting off on your walk check More info. 1) Weather Forecast (BOM Metropolitan District) 3 Grade 3/6 2) Fire Dangers (Greater Sydney Region, unknown) Moderate track Sophies Lookout 3) Park Alerts () 4) Research the walk to check your party has the skills, fitness and This unofficial lookout takes in sweeping views across Sydney Length 4.2 km One way Harbour, over top of Cremorne Point Wharf and 'Sophie's Place' equipment required 5) Agree to stay as a group and not leave anyone to walk solo cafe. -

AN AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURAL SAGA This Draft Summary Clarifies A

AN AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURAL SAGA This draft summary clarifies a 60 year political saga in Australian architectural politics, beginning with the arrival in Sydney of Harry Seidler in 1948 and continuing via his widow Penelope and her supporters after Seidler’s death in 2006. The angle for this version of the saga focuses on architectural politics around author Davina Jackson’s corruptly failed PhD thesis on Seidler’s main early rival in Sydney, Douglas Snelling. An earlier version of this text has been submitted to the Victorian Ombudsman, the NSW Board of Architects, and other relevant government agencies. It also has been circulated to key leaders of Australia’s architectural culture (including Michael Bryce at the Governor General’s Office) – with no questioning of the facts or interpretations. Three lawyers have seen this text and while one advises ‘this saga is so shocking it can never be officially admitted’, the facts have been so comprehensively recorded, circulated and witnessed, there is no realistic potential for the Seidlers, or other named protagonists, to deny their roles either. ......... In the age of the leak and the blog, of evidence extraction and link discovery, truths will either out or be outed, later if not sooner. This is something I would bring to the attention of every diplomat, politician and corporate leader: The future, eventually, will find you out. The future, wielding unimaginable tools of transparency, will have its way with you. In the end, you will be seen to have done that which you did. —William Gibson. 2003. ‘The Road to Oceania’ in The New York Times, June. -

A Swarm of Fish

A Swarm of Fish information and connections are provided by Gevork Hartoonian, Philip Drew, Philip Goad, Richard Blythe, Hannah Lewi, Stephen Neille, Elizabeth Musgrave, Tom Heneghan, and Peter Wilson, the authors featured in this catalogue. Claudia Perren All inspiration from Europe, America, and Asia acknowledged, Australian archi- tects did, however, develop an independent expression of modernism. Standards Modernism, born in Europe, underwent a long process of maturation before reach- and methods of modernism such as light construction, innovative use of new mate- Glenn Murcutt, Douglas ing Australia, arriving on fertile soil. The climate in Australia seems to demand an rials, pilotis, prefabricated elements simplifying production and assembly,the open Murcutt House, Belrose, architecture which, according to the principles of modernism, is based on light, air, plan, and the Frankfurt kitchen have been adopted by them, adapting these to the New South Wales, 1972 and sun. But not exclusively. The exhibition Living the Modern–Australian Australian lifestyle—be it single-family residences or in residential skyscrapers Architecture presents the development of modern architecture in Australia, specific (Aaron Bolot, Pottspoint, 1951; Frederick Romberg, Stanhill Flats, Melbourne, 1950; in terms of culture, location, and climate, by displaying its residential architecture. Douglas Forsyth Adams, The Chilterns, Rose Bay, 1954; Harry Seidler, Horizon The spotlight is set upon twenty-five architects who have adopted, utilized, trans- Apartments, Darlinghurst, 1999). Modernism in Australia is a widely strewn phe- formed, interpreted, and altered aspects of modernism in the last fifteen years. nomenon, not a peculiarity limited to social housing or to interested designers and Thus, for the first time, this exhibition provides a portrait of the significantly inter- architects.