A Study of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (Roscas) in Toronto’S Inner Suburbs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visions of the Future

WALTER GORDON SYMPOSIUM 2019 Canada 2050: Visions of the Future Presented with the generous support of WALTER GORDON SYMPOSIUM 2019 #wgs2019 Canada 2050: Visions of the Future Acknowledgement of Traditional Lands We would like to acknowledge this sacred land upon which the University of Toronto operates. It has been a site of human activity for over 15,000 years. In this time, it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Tkaronto–the place in the water where the trees are standing–is in the Dish-With-One-Spoon territory. The Dish-With-One-Spoon is a treaty between the Anishinaabe, Mississaugas, and Haudenosaunee that binds them to share and protect the land. As with other traditional agreements between the First Peoples of this area, the treaty is marked with a wampum belt. Subsequent Indigenous Nations and peoples, Europeans and all newcomers, have been invited into this treaty alongside the original stewards of this land in the spirit of peace, friendship, and respect. Today, the meeting place of Toronto is still home to many Indigenous peoples from across Turtle Island and we are grateful for the opportunity to live, work, and play in this community. 1 WALTER GORDON SYMPOSIUM 2019 #wgs2019 Canada 2050: Visions of the Future A Note from the Organizing Committee We would like to thank you for your interest in the 2019 Walter Gordon Symposium. We hope you are as excited as we are to hear from the amazing journalists, academics, and thought leaders here today who have graciously agreed to share their knowledge and ideas on a number of important topics related to this year’s theme: Canada 2050: Visions of the Future. -

Downloadable Data Sets Are Available Online

2016 ONTARIO ECONOMIC OUTLOOK AND FISCAL REVIEWBUILDING ONTARIO UP FOR EVERYONE 2016 ONTARIO ECONOMIC OUTLOOK AND FISCAL REVIEW ISSN 1483-5967 (PRINT) ISSN 1496-2829 (PDF /HTML) © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016 The Honourable CHARLES SOUSA Minister of Finance Background Papers PERSPECTIVES ÉCONOMIQUES ET REVUE FINANCIÈRE DE L’ontARIO 2016 PERSPECTIVES ÉCONOMIQUES ET REVUE FINANCIÈRE DE L’ontARIO BUILDING ONTARIO UP FOR EVERYONE 2016 ONTARIO ECONOMIC OUTLOOK AND FISCAL REVIEW The Honourable CHARLES SOUSA Minister of Finance Background Papers For general inquiries regarding the Building Ontario Up for Everyone — 2016 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Background Papers, please call: Toll-free English & French inquiries: 1-800-337-7222 Teletypewriter (TTY): 1-800-263-7776 For electronic copies of this document, visit our website at ontario.ca/fallupdate © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016 ISSN 1483-5967 (Print) ISSN 1496-2829 (PDF/HTML) Ce document est disponible en français sous le titre : Favoriser l’essor de l’Ontario pour tous — Perspectives économiques et revue financière de l’Ontario 2016, Documents d’information Foreword Foreword Introduction Like most jurisdictions around the world, Ontario was affected by the global economic recession that began in 2008. But instead of cutting jobs and services, we created a plan to build Ontario up. We chose to improve our schools, strengthen health care and invest in modern infrastructure. We chose to support our business community so it can rise to meet the challenges of a technology‐ driven, competitive global economy. Our plan is working. Ontario’s economy has continued to grow in an uncertain global environment. -

Rethinking Municipal Finance for the New Economy

MOWAT RESEARCH #187 | MARCH 2019 Rethinking Municipal Finance for the New Economy BY SUNIL JOHAL, KIRAN ALWANI, JORDANN THIRGOOD & PETER SPIRO Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank those who participated in this research project as interviewees for generously sharing their time, expertise and perspectives. Special thanks to Enid Slack and Reuven Shlozberg for their critical review and contributions, and Elaine Stam for her design work on this report. All content and any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Mowat Centre would like to thank the Region of Peel for commissioning and providing financial support for this report, as well as the regional staff for their helpful contributions. The content, conclusions and recommendations expressed in the report are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Region. Authors SUNIL JOHAL JORDANN THIRGOOD Policy Director Policy Associate Sunil is frequently invited to speak about the future of work, After joining Mowat in 2015, Jordann contributed to a variety technology and social policy at conferences in Canada and of projects on fiscal federalism, the sharing economy, and abroad. He has contributed expert commentary and advice the impact of technological innovation on Canada’s labour on regulatory and policy issues to a range of organizations market and social programs. Prior to this, she spent two and media outlets, including the G-20, World Economic years working in the financial sector and ran a pro bono Forum, Brookings Institution, The Globe and Mail, The policy consulting firm for non-profit organizations in the GTA. Toronto Star, CBC Radio and Television, CTV News, The Jordann holds a Master of Public Policy degree from the Guardian, Maclean’s, The Ottawa Citizen, Policy Options, TVO University of Toronto, and an Honours degree in International and the OECD. -

York University Board of Governors Notice of Meeting

York University Board of Governors Notice of Meeting Friday, 13 December 2019, 12:00 to 3:00 pm 5th Floor Kaneff Tower, Keele Campus PAGE I. CLOSED SESSION II. OPEN SESSION – 12:45pm approximately Chair’s Items (P. Tsaparis) 12:45 pm Report on Items Decided in the Closed Session Consent Agenda Approval Executive Committee (P. Tsaparis) Action Taken On Behalf of the Board .......................................................................... 1 President’s Items (R. Lenton) 12:55 pm MAS -3 update (material to be posted separately) Markham Centre Campus update Kudos Report............................................................................................................... 2 Academic Resources Committee (B. White) 1:10 pm President’s Report on Appointments, Tenure and Promotion (For approval) .............. 5 Establishment of the Faculty of Urban and Environmental Change (For approval) ..... 8 External Relations Committee (F. Accinelli) 1:25 pm Points of Pride ......................................................................................................... 79 Board Engagement Plan ........................................................................................... 80 Finance and Audit Committee (W. Hatanaka) 1:30 pm Capital Projects (For approval) • Washroom Renewal, Phase 1: Project Budget ................................................... 82 • Classroom Renewal, Phase 1: Project Budget ..................................................... 84 • Glendon Window Replacement: Project Budget ................................................ -

Mowat Centre ANNUAL REPORT 2011 – 2012 2 Mowat Centre

MOWAT CENTRE ANNUAL REPORT 2011 – 2012 2 Mowat Centre DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE his report represents a milestone for the Mowat TCentre. It is our first annual report and its production signifies a more mature phase of our existence. As Mowat completes its third year, we are focused on sustaining our reputation and consolidating our growth. We are moving from our initial start-up phase, where our focus was producing and commu- nicating high quality applied public policy research, were identified in our report. We expect that this is- to the next stage of our organizational life. sue will continue to be a focus of public debate and further reforms will be forthcoming and the Mowat Within this new phase we will maintain our com- Centre will continue to deepen its expertise on mitment to quality and impact while investing issues relating to income security, unemployment more time and resources toward the profession- insurance, labour market training and the unique alization and development of our organization in ways these play out in different regions across the a manner that will support our growth over the country. medium- and long-term. Our research on voter equality has had an even The past three years have laid a strong foundation greater impact on policy debate, with many of our on which to build. The next challenge for Mowat is recommendations finding their way into new fed- to build on our organizational successes in order eral legislation. The work from the Mowat team has to ensure that we can withstand changes in leader- had a measurable impact on Canada’s move toward ship, personnel, governments and policy cycles – representation-by-population, and as federally- whenever they arise. -

Regional Differences in Ontario

MOWAT RESEARCH #184 | FEBRUARY 2019 confederation of tomorrow 2.0 Portraits 2017 Regional Differences in Ontario BY KIRAN ALWANI & ANDREW PARKIN Acknowledgements The Mowat Centre would like to thank a number of colleagues who provided advice on the methodology and the questionnaire, including The Portraits 2017 survey was conducted with Heather Marshall and Lucas Marshall (Mission Research), Keith Neuman support from Alain-G. Gagnon, holder of the Canada (Environics Institute), Alain-G. Gagnon (Université du Québec à Montréal), Research Chair in Quebec and Canadian Studies Bob Wolfe (School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University), Claire Durand and director at the Centre d’analyse politique: Constitution et Fédéralisme, based at UQAM. (Université de Montréal), and Peter Loewen (School of Public Policy and Governance, University of Toronto). The authors would also like to thank Khuong Truong, Brad Seward and Deepti Kapadia for conducting additional data analysis for this report, as well as Elaine Stam and Reuven Shlozberg for their roles in producing this report. Finally, we would like to thank the report’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. Authors KIRAN ALWANI ANDREW PARKIN Policy Associate Director Kiran joined the Mowat Centre in October 2017, and has Andrew Parkin is the Director of the Mowat Centre. since contributed to a variety of social and economic policy Andrew has previously held a variety of positions projects. Previously, she has worked in a range of research including Director General of the Council of Ministers of and policy analysis roles, including with the Asia Pacific Education Canada (CMEC), Associate Executive Director Foundation of Canada, the Canada-ASEAN Business and Director of Research and Program Development Council, and the Conference Board of Canada. -

Read Spring/Summer 2015 Newsletter

Spring/Summer Newsletter 2015 Members of the MPP Class of 2015 pose for a group photo at June 12's Convocation Reception. Director's Message Welcome to the late spring/early summer version of our newsletter and happy Canada Day! It has been an exciting and busy semester at SPPG and I'm delighted to provide you with this update on the School's activities. Earlier this year, SPPG's Founding Director Mark Stabile announced that he would be stepping down as Director of the School after eight wonderful years. On behalf of the entire SPPG community, I would like to thank Mark for his leadership and for the incredible contributions he has made to the School as Founding Director. In honour of his steadfast leadership, mentorship, and advocacy on behalf of the School, the Mark Stabile Founding Director Fund has been established to annually award an outstanding SPPG student for demonstrated excellence in a student leadership initiative. We humbly request that you consider donatingto the Fund. It is a great opportunity to both honour Professor Stabile's contributions to the School, as well as support the SPPG community's vibrant student leadership. By the time you read this newsletter, our first-year Master of Public Policy students will have begun their internships. These positions are at all levels of government, as well as non-profit organizations, think tanks, and private companies. The internships provide a valuable complement to our students' classroom learning and allow them to further develop their professional skills. I would like to thank all of our internship partners for making available these valuable opportunities to our students and I wish our students well in their new roles. -

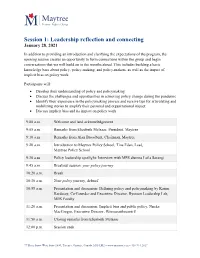

Session 1: Leadership Reflection and Connecting January 28, 2021

Session 1: Leadership reflection and connecting January 28, 2021 In addition to providing an introduction and clarifying the expectations of the program, the opening session creates an opportunity to form connections within the group and begin conversations that we will build on in the months ahead. This includes building a basic knowledge base about policy, policy-making, and policy-makers, as well as the impact of implicit bias on policy work. Participants will: • Develop their understanding of policy and policymaking • Discuss the challenges and opportunities in achieving policy change during the pandemic • Identify their experience in the policymaking process and receive tips for articulating and mobilizing stories to amplify their personal and organizational impact • Discuss implicit bias and its impact on policy work 9:00 a.m. Welcome and land acknowledgement 9:05 a.m. Remarks from Elizabeth McIsaac, President, Maytree 9:10 a.m. Remarks from Alan Broadbent, Chairman, Maytree 9:20 a.m. Introduction to Maytree Policy School, Tina Edan, Lead, Maytree Policy School 9:30 a.m. Policy leadership spotlight: Interview with MPS alumna Leila Sarangi 9:45 a.m. Breakout session: your policy journey 10:20 a.m. Break 10:30 a.m. Your policy journey, debrief 10:55 a.m. Presentation and discussion: Defining policy and policymaking by Karim Bardeesy, Co-Founder and Executive Director, Ryerson Leadership Lab, MPS Faculty 11:20 a.m. Presentation and discussion: Implicit bias and public policy, Nneka MacGregor, Executive Director, WomenatthecentrE 11:50 a.m. Closing remarks from Elizabeth McIsaac 12:00 p.m. Session ends 77 Bloor Street West, Suite 1600, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 1M2 • www.maytree.com • 416-944-2627 Speaker bios Alan Broadbent, Chairman, Maytree Alan Broadbent is Chairman and Founder of Maytree, and Chairman and CEO of Avana Capital Corporation. -

P. E. (Penny Elizabeth) BRYDEN

P. E. (Penny Elizabeth) BRYDEN Education: 1970 - 1983 Primary and secondary schools: Waterloo, Ontario. 1987 B.A. Honours History, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario 1988 M.A., York University, North York, Ontario. 1994 Ph.D., York University, North York, Ontario. Fields of specialization: Canadian history American history Canadian government and politics Dissertation: “Liberal Politics and Social Policy in the Pearson Era, 1957 -1968” Supervisor: J. L. Granatstein Employment: 2013- Full Professor, University of Victoria 2005-2013 Associate Professor with tenure, University of Victoria 2000-2005 Associate Professor with tenure, Mount Allison University 1999-2003 Head of Department of History and Canadian Studies, Mount Allison University 1994-2000 Assistant Professor, Mount Allison University, Sackville, New Brunswick (tenure-track, 1995) 1993-1994 McCain Post-Doctoral Fellow in the Arts, Mount Allison University, Sackville, New Brunswick Publications: Books: ‘A Justifiable Obsession’: Conservative Ontario’s Relations with Ottawa, 1943-1985 Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013. (edited with Colin Coates, Maureen Lux, Lynne Marks, Marcel Martel and Daniel Samson) Visions: The Canadian History Modules Project Toronto: Nelson, 2011. Individual modules edited by P. E. Bryden: 2 Confederation: What Kind of Country Are We To Have? (pp. 1-48); The Great War: Leaders, Followers and Record-Keepers (pp. 1-48); Protest, Parties and Politics Between the Wars, 1919-1939 (pp. 1-48) The Great Depression in Canada: How Did People Cope? (pp. 1-48) Constitutional Negotiations in Late 20th Century Canada: Will We Survive? (pp. 1-48) (edited with Dimitry Anastakis) Framing Canadian Federalism Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009. (edited with Michael J. Tucker and Raymond B. -

Policy Transformation in Canada: Is the Past Prologue?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hughes Tuohy, Carolyn (Ed.); Borwein, Sophie (Ed.); Loewen, Peter John (Ed.); Potter, Andrew (Ed.) Book — Published Version Policy transformation in Canada: Is the past prologue? Provided in Cooperation with: University of Toronto Press Suggested Citation: Hughes Tuohy, Carolyn (Ed.); Borwein, Sophie (Ed.); Loewen, Peter John (Ed.); Potter, Andrew (Ed.) (2019) : Policy transformation in Canada: Is the past prologue?, ISBN 978-1-4875-2324-4, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, http://hdl.handle.net/1807/94443 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/213907 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu POLICY TRANSFORMATION IN CANADA Is the Past Prologue? Canada’s centennial anniversary in 1967 coincided with a period of transformative public policymaking. -

PPG1000: GOVERNANCE and INSTITUTIONS School of Public Policy and Governance University of Toronto Fall 2015

PPG1000: GOVERNANCE AND INSTITUTIONS School of Public Policy and Governance University of Toronto Fall 2015 Section L0101 Section L0102 Wednesday 2-4 Wednesday 2-4 CG 160 CG 361 Prof. Phil Triadafilopoulos Prof. Linda White [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: Monday 1-2, or by appt. Office Hours: Wednesday 1-2, or by appt. Office Location: Canadiana 61B Office Location: Canadiana 319 Telephone: 416-978-7035 Telephone: 416-978-2857 Section L0103 Section L0104 Wednesday 2-4 Monday 12-2 UC 314 CG 160 Prof. Gabriel Eidelman Prof. Phil Triadafilopoulos [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 1-2, or by appt. Office Hours: Monday 2-3, or by appt. Office Location: Canadiana 61F Office Location: Canadiana 61B Telephone: 416-978-7035 This course is intended to provide foundational knowledge of key governance structures and political institutions at the federal, provincial, and municipal levels in Canada. Together, we examine the Constitution, the Westminster parliamentary system, federalism, and the courts. We consider emerging challenges to existing institutions, including the rise of cities, demands for self-government among Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples, and the transition from government to governance, and conclude by reflecting on the quality of Canada’s democratic institutions in comparative perspective. The course is designed as a discussion-intensive seminar. Students are expected to complete each week’s required readings in advance, attend every class, and contribute -

HOW OTTAWA SPENDS 2017-2018 CANADA @150 1 How Ottawa Spends

EDITED BY KATHERINE A. H. GRAHAM AND ALLAN M. MASLOVE HOW OTTAWA SPENDS 2017-2018 CANADA @150 1 How Ottawa Spends CONTENTS Preface ..........................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER 1 - Introduction: Canada @150 Katherine A. H. Graham & Allan M. Maslove .............................................................................4 POLICY BRIEFS CHAPTER 2 - A Post Secondary Education Dialogue for Canada Allan Tupper & Robert Harmsen .............................................................................................. 20 CHAPTER 3 - Overhauling NAFTA: Implications for Canadian Trade Policy Natalia Boliari ............................................................................................................................32 CHAPTER 4 - Science and innovation policy for Canada’s next 150 years Peter WB Phillips, Graeme Jobe, Adity Das Gupta, Sarah Juma, Paul Trujillo Jacome, Samuel Kanyoro Karba, Achint Rastogi & Michael Horvath ................46 CHAPTER 5 - Predictably Unpredictable: The Problem with Equalization from a Provincial Budgeting Perspective Erich Hartmann .........................................................................................................................59 CHAPTER 6 - The Politics of Intergovernmental Transfers in Canada Andrew Seto & Christopher Stoney ...........................................................................................69 CHAPTER 7 - Investing in Indigenous Youth Employment