The Chariot Drawn by Birds Deserves Some Comment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Against Thebes1

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 4:2 2018 Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri General Editors Guido Avezzù (Executive Editor), Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editor Francesco Lupi. Editorial Staff Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, Maria Serena Marchesi, Antonietta Provenza, Savina Stevanato. Layout Editor Alex Zanutto. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Daniela Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2018 SKENÈ Published in December 2018 All rights reserved. ISSN 2421-4353 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. SKENÈ Theatre and Drama Studies http://www.skenejournal.it [email protected] Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) Contents Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson Eric Nicholson – Introduction 5 Anton Bierl – The mise en scène of Kingship and Power in 19 Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes: Ritual Performativity or Goos, Cledonomancy, and Catharsis Alessandro Grilli – The Semiotic Basis of Politics 55 in Seven Against Thebes Robert S. -

The Shield As Pedagogical Tool in Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes

АНТИЧНОЕ ВОСПИТАНИЕ ВОИНА ЧЕРЕЗ ПРИЗМУ АРХЕОЛОГИИ, ФИЛОЛОГИИ И ИСТОРИИ ПЕДАГОГИКИ THE SHIELD AS PEDAGOGICAL TOOL IN AESCHYLUS’ SEVEN AGAINST THEBES* Victoria K. PICHUGINA The article analyzes the descriptions of warriors in Aeschylus’s tragedy Seven against Thebes that are given in the “shield scene” and determines the pedagogical dimension of this tragedy. Aeschylus pays special attention to the decoration of the shields of the com- manders who attacked Thebes, relying on two different ways of dec- orating the shields that Homer describes in The Iliad. According to George Henry Chase’s terminology, in Homer, Achilles’ shield can be called “a decorative” shield, and Agamemnon’s shield is referred to as “a terrible” shield. Aeschylus turns the description of the shield decoration of the commanders attacking Thebes into a core element of the plot in Seven against Thebes, maximizing the connection be- tween the image on the shield and the shield-bearer. He created an elaborate system of “terrible” and “decorative” shields (Aesch. Sept. 375-676), as well as of the shields that cannot be categorized as “ter- rible” and “decorative” (Aesch. Sept. 19; 43; 91; 100; 160). The analysis of this system made it possible to put forward and prove three hypothetical assumptions: 1) In Aeschylus, Eteocles demands from the Thebans to win or die, focusing on the fact that the city cre- ated a special educational space for them and raised them as shield- bearers. His patriotic speeches and, later, his judgments expressed in the “shield scene” demonstrate a desire to justify and then test the educational concept “ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς” (“either with it, or upon it”) (Plut. -

ELEGY 397 ( ); K. Strecker, “Leoninische Hexameter Und

ELEGY 397 (); K. Strecker, “Leoninische Hexameter und speare, Two Gentlemen of Verona) can be recommended Pentameter in . Jahrhundert,” Neues Archiv für ältere to a would-be seducer. T is composite understanding deutsche Geschichtskunde (); C. M. Bowra, Early of the genre, however, is never fully worked out and Greek Elegists, d ed. (); P. F r i e d l ä n d e r , Epigram- gradually fades. mata: Greek Inscriptions in Verse from the Beginnings to T e most important cl. models for the later devel. of the Persian Wars ( ); M. Platnauer, Latin Elegiac Verse elegy are *pastoral: the lament for Daphnis (who died (); L. P. Wilkinson, Golden Latin Artistry ( ); of love) by T eocritus, the elegy for Adonis attributed T. G. Rosenmeyer, “Elegiac and Elegos,” California to Bion, the elegy on Bion attributed to Moschus, and Studies in Classical Antiquity (); D. Ross, Style another lament for Daphnis in the fi fth *eclogue of and Tradition in Catullus ( ); M. L. West, Studies in Virgil. All are stylized and mythic, with hints of ritual; Greek Elegy and Iambus ( ); A.W.H. Adkins, Poetic the fi rst three are punctuated by incantatory *refrains. Craft in the Early Greek Elegists ( ); R. M. Marina T e elegies on Daphnis are staged performances within Sáez, La métrica de los epigramas de Marcial (). an otherwise casual setting. Nonhuman elements of the T.V.F. BROGAN; A. T. COLE pastoral world are enlisted in the mourning: nymphs, satyrs, the landscape itself. In Virgil, the song of grief is E L E G I A C S T A N Z A , elegiac quatrain, heroic qua- paired with one celebrating the dead man’s apotheosis; train. -

Morpho-Phonology and the Greek Glides

Morpho-phonology and the Greek glides In the Greek phonological literature there have been many attempts to uncover the factors regulating hiatus (i.e. vocalic sequences) and synizesis (i.e. glide formation) in Modern Greek (Kazazis 1968, Warburton 1976, Setatos 1974, Nyman 1981, Deligiorgis 1987, Malikouti-Drachman & Drachman 1990). There is a cross-linguistic tendency to avoid hiatus, as shown for example in Casali (1997), but in Modern Greek, hiatus is avoided only in some cases. These two processes, hiatus and synizesis, are seen as two opposing forces in Greek phonology yielding either words with vocalic sequences such as [io] ~ [iu], [ia] in (2) or words where a vowel turns into a glide to avoid hiatus as in [i] ~ [ju], [ja] in (1). Synizesis is also compounded by strengthening or hardening in some cases (1a-d) resulting in the fricativization of the glides. While both classes of words in (1) and (2) involve neuter nouns, it is only the former class that involves [i]~[j] alternations between the nominative singular form and the rest. The data below thus give us two types of contrast: i) an [i]~[j] alternation between the nominative singular and the rest in (1) and ii) a [j]~[i] contrast between the genitive and plural forms of (1) versus those of (2). In the latter class hiatus is tolerated. NOM. SING GEN. SING NOM. PLURAL GLOSS (1) a. po. ði po. ðʝú po. ðʝa foot b. ðo.ka.ri ðo.ka.rʝú ðo.ka.rʝa girder c. ko.lo.ci.θi ko.lo.ci.θç ú ko.lo.ci.θça pumpkin d. -

Quantitative Metathesis in Ancient Greek

Quantitative Metathesis in Ancient Greek Anita Brown Bryn Mawr College December 2017 Abstract This paper explores the phenomenon known as 'quantitative metathesis' in Ancient Greek. Historically this change, an apparent metathesis of vowel length, has been considered to be true metathesis by classicists, but recent scholarship has cast suspicion on this notion, not least because metathesis of vowel length is not a known change in any other language. In this paper, I present a review of previous scholarship on Greek quantitative metathesis, in addition to a cross-linguistic survey of general metathesis, with special attention to autosegmental theory. I conclude that Greek quantitative metathesis is not true metathesis, but rather a retention and reassociation of abstract timing units through the two individual (and well-attested) processes of antevocalic shortening and compensatory lengthening. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Introduction to Ancient Greek 5 1.2 Introduction to Quantitative Metathesis 6 1.2.1 A-stem 6 1.2.2 Athematic stems 7 1.3 Introduction to Autosegmental Phonology 8 2 Greek meter and accent 9 2.1 Meter 9 2.2 Accent 11 3 Overview of metathesis 12 3.1 CV metathesis in Rotuman 13 3.1.1 As deletion and reattachment (Besnier 1987) 13 3.1.2 As compensatory metathesis (Blevins & Garrett 1998) 13 3.2 CV metathesis in Kwara'ae ............... 14 3.3 Compensatory lengthening from CV metathesis in Leti . 15 3.4 VV metathesis .. 16 3.5 Syllabic metathesis 17 4 Analyses of quantitative metathesis 18 4.1 QM as timing-slot transfer ..... 18 4.2 QM as CL/preservation of quantity. -

Greek God Pantheon.Pdf

Zeus Cronos, father of the gods, who gave his name to time, married his sister Rhea, goddess of earth. Now, Cronos had become king of the gods by killing his father Oranos, the First One, and the dying Oranos had prophesied, saying, “You murder me now, and steal my throne — but one of your own Sons twill dethrone you, for crime begets crime.” So Cronos was very careful. One by one, he swallowed his children as they were born; First, three daughters Hestia, Demeter, and Hera; then two sons — Hades and Poseidon. One by one, he swallowed them all. Rhea was furious. She was determined that he should not eat her next child who she felt sure would he a son. When her time came, she crept down the slope of Olympus to a dark place to have her baby. It was a son, and she named him Zeus. She hung a golden cradle from the branches of an olive tree, and put him to sleep there. Then she went back to the top of the mountain. She took a rock and wrapped it in swaddling clothes and held it to her breast, humming a lullaby. Cronos came snorting and bellowing out of his great bed, snatched the bundle from her, and swallowed it, clothes and all. Rhea stole down the mountainside to the swinging golden cradle, and took her son down into the fields. She gave him to a shepherd family to raise, promising that their sheep would never be eaten by wolves. Here Zeus grew to be a beautiful young boy, and Cronos, his father, knew nothing about him. -

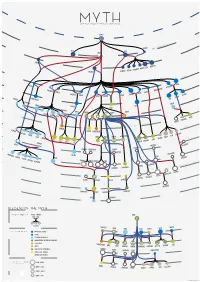

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

The Two Voices of Statius: Patronymics in the Thebaid

The Two Voices of Statius: Patronymics in the Thebaid. Kyle Conrau-Lewis This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne, November 2013. 1 This is to certify that: 1. the thesis comprises only my original work towards the degree of master of arts except where indicated in the Preface, 2. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, 3. the thesis is less than 50,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. 2 Contents Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1 24 Chapter 2 53 Chapter 3 87 Conclusion 114 Appendix A 117 Bibliography 121 3 Abstract: This thesis aims to explore the divergent meanings of patronymics in Statius' epic poem, the Thebaid. Statius' use of language has often been characterised as recherché, mannered and allusive and his style is often associated with Alexandrian poetic practice. For this reason, Statius' use of patronymics may be overlooked by commentators as an example of learned obscurantism and deliberate literary self- fashioning as a doctus poeta. In my thesis, I argue that Statius' use of patronymics reflects a tension within the poem about the role and value of genealogy. At times genealogy is an ennobling feature of the hero, affirming his military command or royal authority. At other times, a lineage is perverse as Statius repeatedly plays on the tragedy of generational stigma and the liability of paternity. Sometimes, Statius points to the failure of the son to match the character of his father, and other times he presents characters without fathers and this has implications for how these characters are to be interpreted. -

Online Companion to a Historical Phonology of English

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova © Donka Minkova, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10.5/12 Janson by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 3467 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3468 2 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3469 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7755 9 (epub) The right of Donka Minkova to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements x List of abbreviations and symbols xii A note on the Companion to A Historical Phonology of English xv 1 Periods in the history of English 1 1.1 Periods in the history of English 2 1.2 Old English (450–1066) 2 1.3 Middle English (1066–1476) 9 1.4 Early Modern English (1476–1776) 15 1.5 English after 1776 17 1.6 The evidence for early pronunciation 20 2 The sounds of English 24 2.1 The consonants of PDE 24 2.1.1 Voicing 26 2.1.2 Place of articulation 27 2.1.3 Manner of articulation 29 2.1.4 Short and long consonants 31 2.2 The vowels of PDE 32 2.2.1 Short and long vowels 35 2.2.2 Complexity: monophthongs and diphthongs 37 2.3 The syllable: some basics 39 2.3.1 Syllable structure 39 2.3.2 Syllabifi cation 40 2.3.3 Syllable weight 43 2.4 Notes on vowel representation 45 2.5 Phonological change: some types and causes 46 3 Discovering the earliest links: Indo- European -

Q82CPC: the Tragedy of Oedipus | University of Nottingham

09/24/21 Q82CPC: The tragedy of Oedipus | University of Nottingham Q82CPC: The tragedy of Oedipus View Online The first case-study 1. Ahrensdorf, P. J., Pangle, T. L., Sophocles & ebrary. The Theban plays. vol. Agora Editions (Cornell University Press, 2014). 2. Berkoff, S. & Berkoff, S. Oedipus. (2013). 3. Wertenbaker, T. & Sophocles. Oedipus tyrannos. (2013). 4. Mulroy, D. D., Moon, W. G., Sophocles & ebrary, Inc. Oedipus Rex. vol. Wisconsin studies in classics (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011). 5. Fainlight, R., Littman, R. J., Sophocles & ebrary, Inc. The Theban plays: Oedipus the king, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone. vol. Johns Hopkins new translations from antiquity (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). 6. McGuinness, F., McGrogarty, C. & Sophocles. Oedipus. Faber plays, (2008). 1/20 09/24/21 Q82CPC: The tragedy of Oedipus | University of Nottingham 7. Storr, F., Sophocles & ebrary. Oedipus trilogy: Oedipus the king, Oedipus at colonus and Antigone. (The Floating Press, 2008). 8. Slavitt, D. R., Sophocles & ebrary, Inc. The Theban plays of Sophocles. (Yale University Press, 2007). 9. Greig, D. Oedipus the visionary. (Capercaillie Books, 2005). 10. Jebb, R. C., Easterling, P. E., Rusten, J. S. & Sophocles. Sophocles: plays, Oedipus Tyrannus. vol. Classic commentaries on Latin & Greek texts (Bristol Classical, 2004). 11. Bagg, R., Bagg, M. & Sophocles. The Oedipus plays of Sophocles: Oedipus the king, Oedipus at Kolonos, Antigone. (University of Massachusetts Press, 2004). 12. Meineck, P., Woodruff, P. & Sophocles. Theban plays. (Hackett Pub, 2003). 13. Taylor, D. & Sophocles. Plays: one. vol. Methuen world classics (Methuen Drama, 1998). 14. Hall, E. & Sophocles. Antigone: Oedipus the King ; Electra. vol. World’s classics (Oxford University Press, 1994). -

Greek Mythology Gods and Goddesses

Greek Mythology Gods and Goddesses Uranus Gaia Cronos Rhea Hestia Demeter Hera Hades Poseidon Zeus Athena Ares Hephaestus Aphrodite Apollo Artemis Hermes Dionysus Book List: 1. Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey - Several abridged versions available 2. Percy Jackson’s Greek Gods by Rick Riordan 3. Percy Jackson and the Olympians series by, Rick Riordan 4. Treasury of Greek Mythology by, Donna Jo Napoli 5. Olympians Graphic Novel series by, George O’Connor 6. Antigoddess series by, Kendare Blake Website References: https://www.greekmythology.com/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_tree_of_the_Greek_gods https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/greek-mythology King of the Gods God of the Sky, Thunder, Lightning, Order, Law, Justice Married to: Hera (and various consorts) Symbols: Thunderbolt, Eagle, Oak, Bull Children: MANY, including; Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Hermes, Persephone, Hercules, Helen of Troy, Perseus and the Muses Interesting Story: When father, Cronos, swallowed all of Zeus’ siblings (Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades and Poseidon) Zeus was the one who killed Cronos and rescued them. Roman Name: Jupiter God of the Sea Storms, Earthquakes, Horses Married to: Amphitrite (various consorts) Symbols: Trident, Fish, Dolphin, Horse Children: Theseus, Triton, Polyphemus, Atlas, Pegasus, Orion and more Interesting Story: Has a hatred of Odysseus for blinding Poseidon’s son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. Roman Name: Neptune God of the Underworld The Dead, Riches Married to : Persephone Symbols: Serpent, Cerberus the Three Headed Dog Children: Zagreus, Macaria, possibly others Interesting Story: Hades tricked his “wife” Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds from the Underworld, binding her to him and forcing her to live in the Underworld for part of each year. -

Relative Chronology and the Language of Epic A

RELATIVE CHRONOLOGY AND THE LANGUAGE OF EPIC A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Brandtly Neal Jones January 2008 © 2008 Brandtly Neal Jones RELATIVE CHRONOLOGY AND THE LANGUAGE OF EPIC Brandtly Neal Jones, Ph. D. Cornell University 2008 The songs of the early Greek epos do not survive with reliable dates attached. The texts provide few references to events outside the songs themselves with which to establish a chronology, and thus much study has centered on the language of the songs. This study takes as its starting point the well-known and influential work of Richard Janko on this topic, especially as presented in his Homer, Hesiod, and the hymns: Diachronic development in epic diction, which seeks to establish relative dates for the songs of the epos through statistical analysis of certain linguistic features found therein. Though Janko's methodology is flawed, it does highlight the principal aspects of the question of the epic language and chronology. This thesis first establishes the problematic relationship between the oral tradition and our textual representatives of that tradition, as well as the consequences of that relationship for the question of chronology. The existence of an Aeolic phase of epic diction is next refuted, with important results for chronology. Finally, the evidence of the Homeric digamma reveals the "paradox of archaism." The epic language can be shown to work in such a way that many apparent archaisms depend crucially on innovative forms for their creation.