Newlands 2020 CV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Against Thebes1

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 4:2 2018 Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri General Editors Guido Avezzù (Executive Editor), Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editor Francesco Lupi. Editorial Staff Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, Maria Serena Marchesi, Antonietta Provenza, Savina Stevanato. Layout Editor Alex Zanutto. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Daniela Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2018 SKENÈ Published in December 2018 All rights reserved. ISSN 2421-4353 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. SKENÈ Theatre and Drama Studies http://www.skenejournal.it [email protected] Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) Contents Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson Eric Nicholson – Introduction 5 Anton Bierl – The mise en scène of Kingship and Power in 19 Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes: Ritual Performativity or Goos, Cledonomancy, and Catharsis Alessandro Grilli – The Semiotic Basis of Politics 55 in Seven Against Thebes Robert S. -

The Shield As Pedagogical Tool in Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes

АНТИЧНОЕ ВОСПИТАНИЕ ВОИНА ЧЕРЕЗ ПРИЗМУ АРХЕОЛОГИИ, ФИЛОЛОГИИ И ИСТОРИИ ПЕДАГОГИКИ THE SHIELD AS PEDAGOGICAL TOOL IN AESCHYLUS’ SEVEN AGAINST THEBES* Victoria K. PICHUGINA The article analyzes the descriptions of warriors in Aeschylus’s tragedy Seven against Thebes that are given in the “shield scene” and determines the pedagogical dimension of this tragedy. Aeschylus pays special attention to the decoration of the shields of the com- manders who attacked Thebes, relying on two different ways of dec- orating the shields that Homer describes in The Iliad. According to George Henry Chase’s terminology, in Homer, Achilles’ shield can be called “a decorative” shield, and Agamemnon’s shield is referred to as “a terrible” shield. Aeschylus turns the description of the shield decoration of the commanders attacking Thebes into a core element of the plot in Seven against Thebes, maximizing the connection be- tween the image on the shield and the shield-bearer. He created an elaborate system of “terrible” and “decorative” shields (Aesch. Sept. 375-676), as well as of the shields that cannot be categorized as “ter- rible” and “decorative” (Aesch. Sept. 19; 43; 91; 100; 160). The analysis of this system made it possible to put forward and prove three hypothetical assumptions: 1) In Aeschylus, Eteocles demands from the Thebans to win or die, focusing on the fact that the city cre- ated a special educational space for them and raised them as shield- bearers. His patriotic speeches and, later, his judgments expressed in the “shield scene” demonstrate a desire to justify and then test the educational concept “ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς” (“either with it, or upon it”) (Plut. -

Greek God Pantheon.Pdf

Zeus Cronos, father of the gods, who gave his name to time, married his sister Rhea, goddess of earth. Now, Cronos had become king of the gods by killing his father Oranos, the First One, and the dying Oranos had prophesied, saying, “You murder me now, and steal my throne — but one of your own Sons twill dethrone you, for crime begets crime.” So Cronos was very careful. One by one, he swallowed his children as they were born; First, three daughters Hestia, Demeter, and Hera; then two sons — Hades and Poseidon. One by one, he swallowed them all. Rhea was furious. She was determined that he should not eat her next child who she felt sure would he a son. When her time came, she crept down the slope of Olympus to a dark place to have her baby. It was a son, and she named him Zeus. She hung a golden cradle from the branches of an olive tree, and put him to sleep there. Then she went back to the top of the mountain. She took a rock and wrapped it in swaddling clothes and held it to her breast, humming a lullaby. Cronos came snorting and bellowing out of his great bed, snatched the bundle from her, and swallowed it, clothes and all. Rhea stole down the mountainside to the swinging golden cradle, and took her son down into the fields. She gave him to a shepherd family to raise, promising that their sheep would never be eaten by wolves. Here Zeus grew to be a beautiful young boy, and Cronos, his father, knew nothing about him. -

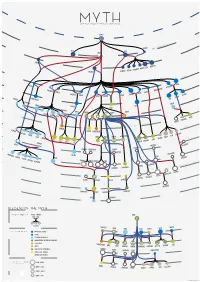

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

The Two Voices of Statius: Patronymics in the Thebaid

The Two Voices of Statius: Patronymics in the Thebaid. Kyle Conrau-Lewis This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne, November 2013. 1 This is to certify that: 1. the thesis comprises only my original work towards the degree of master of arts except where indicated in the Preface, 2. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, 3. the thesis is less than 50,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. 2 Contents Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1 24 Chapter 2 53 Chapter 3 87 Conclusion 114 Appendix A 117 Bibliography 121 3 Abstract: This thesis aims to explore the divergent meanings of patronymics in Statius' epic poem, the Thebaid. Statius' use of language has often been characterised as recherché, mannered and allusive and his style is often associated with Alexandrian poetic practice. For this reason, Statius' use of patronymics may be overlooked by commentators as an example of learned obscurantism and deliberate literary self- fashioning as a doctus poeta. In my thesis, I argue that Statius' use of patronymics reflects a tension within the poem about the role and value of genealogy. At times genealogy is an ennobling feature of the hero, affirming his military command or royal authority. At other times, a lineage is perverse as Statius repeatedly plays on the tragedy of generational stigma and the liability of paternity. Sometimes, Statius points to the failure of the son to match the character of his father, and other times he presents characters without fathers and this has implications for how these characters are to be interpreted. -

Q82CPC: the Tragedy of Oedipus | University of Nottingham

09/24/21 Q82CPC: The tragedy of Oedipus | University of Nottingham Q82CPC: The tragedy of Oedipus View Online The first case-study 1. Ahrensdorf, P. J., Pangle, T. L., Sophocles & ebrary. The Theban plays. vol. Agora Editions (Cornell University Press, 2014). 2. Berkoff, S. & Berkoff, S. Oedipus. (2013). 3. Wertenbaker, T. & Sophocles. Oedipus tyrannos. (2013). 4. Mulroy, D. D., Moon, W. G., Sophocles & ebrary, Inc. Oedipus Rex. vol. Wisconsin studies in classics (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011). 5. Fainlight, R., Littman, R. J., Sophocles & ebrary, Inc. The Theban plays: Oedipus the king, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone. vol. Johns Hopkins new translations from antiquity (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). 6. McGuinness, F., McGrogarty, C. & Sophocles. Oedipus. Faber plays, (2008). 1/20 09/24/21 Q82CPC: The tragedy of Oedipus | University of Nottingham 7. Storr, F., Sophocles & ebrary. Oedipus trilogy: Oedipus the king, Oedipus at colonus and Antigone. (The Floating Press, 2008). 8. Slavitt, D. R., Sophocles & ebrary, Inc. The Theban plays of Sophocles. (Yale University Press, 2007). 9. Greig, D. Oedipus the visionary. (Capercaillie Books, 2005). 10. Jebb, R. C., Easterling, P. E., Rusten, J. S. & Sophocles. Sophocles: plays, Oedipus Tyrannus. vol. Classic commentaries on Latin & Greek texts (Bristol Classical, 2004). 11. Bagg, R., Bagg, M. & Sophocles. The Oedipus plays of Sophocles: Oedipus the king, Oedipus at Kolonos, Antigone. (University of Massachusetts Press, 2004). 12. Meineck, P., Woodruff, P. & Sophocles. Theban plays. (Hackett Pub, 2003). 13. Taylor, D. & Sophocles. Plays: one. vol. Methuen world classics (Methuen Drama, 1998). 14. Hall, E. & Sophocles. Antigone: Oedipus the King ; Electra. vol. World’s classics (Oxford University Press, 1994). -

Greek Mythology Gods and Goddesses

Greek Mythology Gods and Goddesses Uranus Gaia Cronos Rhea Hestia Demeter Hera Hades Poseidon Zeus Athena Ares Hephaestus Aphrodite Apollo Artemis Hermes Dionysus Book List: 1. Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey - Several abridged versions available 2. Percy Jackson’s Greek Gods by Rick Riordan 3. Percy Jackson and the Olympians series by, Rick Riordan 4. Treasury of Greek Mythology by, Donna Jo Napoli 5. Olympians Graphic Novel series by, George O’Connor 6. Antigoddess series by, Kendare Blake Website References: https://www.greekmythology.com/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_tree_of_the_Greek_gods https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/greek-mythology King of the Gods God of the Sky, Thunder, Lightning, Order, Law, Justice Married to: Hera (and various consorts) Symbols: Thunderbolt, Eagle, Oak, Bull Children: MANY, including; Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Hermes, Persephone, Hercules, Helen of Troy, Perseus and the Muses Interesting Story: When father, Cronos, swallowed all of Zeus’ siblings (Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades and Poseidon) Zeus was the one who killed Cronos and rescued them. Roman Name: Jupiter God of the Sea Storms, Earthquakes, Horses Married to: Amphitrite (various consorts) Symbols: Trident, Fish, Dolphin, Horse Children: Theseus, Triton, Polyphemus, Atlas, Pegasus, Orion and more Interesting Story: Has a hatred of Odysseus for blinding Poseidon’s son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. Roman Name: Neptune God of the Underworld The Dead, Riches Married to : Persephone Symbols: Serpent, Cerberus the Three Headed Dog Children: Zagreus, Macaria, possibly others Interesting Story: Hades tricked his “wife” Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds from the Underworld, binding her to him and forcing her to live in the Underworld for part of each year. -

Translating and Adapting Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes in the United

Giovanna Di Martino Translating and Adapting Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes in the United States Σ Skenè Studies II • 4 Table of contents Skenè Studies II • 4 Foreword Giovanna Di Martino1 1. Russian Formalism:Translating “The road which and turns backAdapting on 2 itself” 3 2.Aeschylus’ The Signifier as Pure Seven Form Against Thebes4 3. Seeing as: Wittgenstein’s Duck-rabbit 5 4. The Bakhtin Circle in the United States6 5. Discourse in Art and Life 7 5.1 Speech Genres and Language Games 8 5.2 The Construction of the Utterance 9 6. The Syntactical Relations of Reported Speech 11 7. The Objects of Dialogism: The Familiarity of the Novel 12 8. Dialogization of the Object 13 9. Chronotopes, or the Space/Time of Representation 14 Conclusion 15 Works Cited 16 Index Σ TableSKENÈ ofTheatre contents and Drama Studies Executive Editor Guido Avezzù. General Editors Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editors Bianca Del Villano, Savina Stevanato. Assistant Managing Valentina Adami, Emanuel Stelzer, Roberta Zanoni. ForewordEditors 1 Communication Chiara Battisti, Sidia Fiorato. Staff Giuseppe Capalbo, Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, 1. Russian Formalism:Antonietta “The Provenza. road which turns back on 2 Advisoryitself” Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, 3 Richard Allen Cave, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, 2. The SignifierMarco as Pure De Marinis, Form Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, 4 3. Seeing as: Wittgenstein’sPaul Edmondson, Duck-rabbit Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, 5 Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, 4. The Bakhtin DanielaCircle Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, 6 5. -

'Romantic Poet-Sage of History': Herodotus and His Arion in the Long

Pre-print version of article forthcoming in ‘Herodotus in the 19th Century’, Tom Harrison ed. 'Romantic poet-sage of history': Herodotus and his Arion in the long 19th Century Edith Hall (KCL) This article uses the figure of Arion, the lyric poet from Methymna whose story is told early in Herodotus’ Histories, to explore the adoption of Herodotus, in the long 19th century, as the ‘Romantic poet-sage of History’. This is the title bestowed upon him by the Anglican priest and hymn-writer John Ernest Bode, who in 1853 adapted tales from Herodotus into old English and Scottish ballad forms.1 Herodotus was seen as the prose avatar of poets—of medieval balladeers, lyric singers, epic bards, and even authors of verse drama. These configurations of Herodotus are cast into sharp relief by comparing them with his previous incarnation, in the Early Modern and earlier 18th century, as a writer who most strongly resembled a novelist. Isaac Littlebury, Herodotus’ 1709 translator, was attracted to the historian for the simple reason that in 1701 he had enjoyed success with a previous translation. But the earlier work was certainly not a translation of an ancient historian. Littlebury had translated Fénelon's Télémaque, a work of fantasy fiction derived ultimately from the Posthomerica, perhaps better described as a novel combing a rites-of-passage theme with an exciting travelogue.2 Herodotus-the-novelist did not disappear altogether in the 19th century; one of his most revealing Victorian receptions occurred, in 1855, when he was turned himself into the hero of a travelogue combined with semi-fictionalised biography, J. -

PDF Download

AKAAHMIA A0HNQN KENTPON EPEYNfil TID: APXAIOTHTO~ IBIPA MONOrPA<l>IQN 6 ~QPON TIMHTIKO~ TOMO~ rIA TON KA0HrHTH ~:IIYPO IAKQBI~H EII~HMONIKH EIIIMEAEIA ~E~IIOINA ~ANIHAI~OY A0HNA2OO9 © AKAAfIMIA A0HNQN KENTPON EPEYNJ-Il: Tifl: APXAIOTIITOL AvayvwITTOJtO'UA.OU14 106 73 AEhjva TTJA..210-3664612 - FAX 210-3602448 ISSN 1106-9260 ISBN 978-960-404-160-2 ~QPON TIMHTIKOL TOMOL ITA TON KA0HI'HTH ~IIYPO IAKQBI~H CONTINUITY FROM THE MYCENAEAN PERIOD IN AN HISTORICAL BOEOTIAN CULT OF POSEIDON (AND ERINYS) As is well known, Spyros lakovidis has always been very interested in the full range of Mycenaean culture and its place within the Hellenic tradition, past and present. He has also been interested in detailing the archaeological evidence for what leading researchers call 'the horse of Poseidon' 1, i.e., the terrible earthquake damage that might have contributed to the demise of Mycenaean palatial culture. I offer this exploration into continuity of an unusual cult of Poseidon in Boeotia from the Bronze Age into the classical period, as a modest trib ute to the great breadth of vision and exacting care in research of Professor Iakovidis. Much of the evidence from the Linear B tablets for religion2 can be connected with an extra-palatial element of Mycenaean religious ritual or at least to sanctuary sites out in the landscape and outside the immediate orbit of the palatial centers. The worship of Dionysos is attested in a theophoric name on KN tablet Dv 1501. The reference is to a shepherd on Crete . This at least indicates that religious feeling for Dionysos reached popula tion groups outside the palatial centers and at levels below the upper-class elites at these palatial cen ters. -

From the East to the Moon

From the East to the Moon Towards an international understanding of folktale motif A153.1 Theft of ambrosia: Food of the gods stolen Name: Arjan Sterken Student Number: S3030725 University: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen / University of Groningen Programme: Research Master ‘Religion and Culture’ First Assessor: prof. dr. dr. F.L. Roig Lanzillotta Second Assessor: prof. dr. Theo Meder Word count: 31,095 Summary This thesis gives an answer to the research question ‘how is the motif A153.1 Theft of ambrosia: Food of the gods stolen instantiated and structurally related to one another in different contexts?’ This thesis wishes to re-evaluate the Indo-European theoretical frame by providing a negative control. For this, 66 texts from India, 24 from Greece, and 42 from China (the negative control) are structurally analysed, using an adapted form of structuralism as described by Frog. As a result, the ‘universal’ group is the strongest, meaning that most motifs are shared by Indian, Greek, and Chinese narratives. A little weaker in strength is the Indo-European group, followed by the India-China pair. The similarities between Greek and Chinese narratives are negligible if ignoring the ‘universal’ similarities. From this analysis, two conclusions are drawn: 1) Indo-European reconstruction is valid, as now tested by a negative control; and 2) to understand international folktale motifs which were only considered from its Indo-European data, it is fruitful to apply non- Indo-European data as well. 2 Table of contents Summary . 2 1. Introduction . 8 1.1 Objectives and research questions . 9 1.2 Field of study . 10 2. -

Greek Mythological Horses and the World's Boundary

Marina MILIĆEVIĆ BRADAČ GREEK MYTHOLOGICAL HORSES AND THE WORLD’S BOUNDARY UDK 904.03 Marina Milićević Bradač Primljeno/Received: 2003. 04. 14. HR 10000 Zagreb Prihvaćeno/Accepted: 2003. 09. 15. Department of Archaeology Faculty of Philosophy I. Lučića 3 Greek mythological horses, like Pegasus, Arion, Xanthus, Skyphius and others, show direct and indirect connection with water of any kind. This particular connection between horses and water would not stem from the notions of vegetation and fertility, but from the idea that water is the border between the world of the living and the Otherworld. The horse was psychopompos who carried the soul of the deceased across the border, and he also carried the shaman during his ecstatic journey. Key words: horses, water, sources, Poseidon, Arion, Pegasus, Xanthus, Balius, Skiphius, Skironites, Kyllarus, Erichthonius’ horses, shamanism The catalogue of the Greek horses is tightly mountain Helicon. Not far from Hippoukrene was connected with rivers, springs, and wells - water of another horse’s spring – Aganippe – (Hes. Th. 6). any kind - and with the river divinities* . The general Another Hippoukrene was in Troezen (Paus. 2.31), notion was that the connection stemmed from the and in Ephesus was the source known as Kallipia idea of water as giver of life, especially of plant life, (Plin. NH 5.115). A source named Híppê (after one of and that horses were symbols of the vegetation deities. the Danaids) or Híppeion was situated near Argos That is certainly true of some situations, notably of (Callim. Fr. 66.8). We also have information of the Indo-European horse-sacrifice.