Seven Against Thebes1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

“The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore

The Macksey Journal Volume 1 Article 31 2020 “The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore Julian A. Emole University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.mackseyjournal.org/publications Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, German Linguistics Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Emole, Julian A. (2020) "“The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore," The Macksey Journal: Vol. 1 , Article 31. Available at: https://www.mackseyjournal.org/publications/vol1/iss1/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Johns Hopkins University Macksey Journal. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Macksey Journal by an authorized editor of The Johns Hopkins University Macksey Journal. “The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore Cover Page Footnote The title of this work was inspired by Daniel Ogden's book, "Drakōn: Dragon Myth & Serpent Cult in the Greek & Roman Worlds," and specifically his chapter titled 'The Symmetrical Battle'. His work serves as the foundation for the following outline of the Graeco-Roman dragon and was the inspiration for my own work on the Norse-Germanic dragon. This paper is a condensed version of a much longer unpublished work, which itself is the product of three years worth of ongoing research. -

Arion and the Dolphin

Arion and the Dolphin Arion, semilegendary Greek poet and musician of Methymna in Lesbos. He is said to have invented the dithyramb (choral poem or chant performed at the festival of Dionysus); that is, he gave it literary form. His father’s name, Cycleus, indicates the connection of the son with the cyclic or circular chorus of the dithyramb. None of his works survive, and only one story about his life is known (reported by the historian Herodotus]). After a successful performing tour of Sicily and Magna Graecia, Arion sailed for home. The sight of the treasure he carried roused the cupidity of the sailors, who resolved to kill him and seize his wealth. Arion, as a last favour, begged permission to sing a song. The sailors consented, and the poet, standing on the deck of the ship, sang a dirge accompanied by his lyre. He then threw himself overboard; but he was miraculously borne up in safety by a dolphin, which had been charmed by the music. Thus he proceeded to Corinth, arriving before the ship. There Arion’s friend Periander, tyrant of Corinth, eventually learned the truth by a stratagem. Summoning the sailors, he demanded what had become of the poet. Upon affirming that he had remained behind, they were suddenly confronted by Arion himself. The sailors confessed and were punished, and Arion’s lyre and the dolphin became the constellations Lyra and Delphinus. Source Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Arion". Encyclopedia Britannica, Invalid Date, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Arion- Greek-poet-and-musician. Accessed 24 June 2021. -

The Shield As Pedagogical Tool in Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes

АНТИЧНОЕ ВОСПИТАНИЕ ВОИНА ЧЕРЕЗ ПРИЗМУ АРХЕОЛОГИИ, ФИЛОЛОГИИ И ИСТОРИИ ПЕДАГОГИКИ THE SHIELD AS PEDAGOGICAL TOOL IN AESCHYLUS’ SEVEN AGAINST THEBES* Victoria K. PICHUGINA The article analyzes the descriptions of warriors in Aeschylus’s tragedy Seven against Thebes that are given in the “shield scene” and determines the pedagogical dimension of this tragedy. Aeschylus pays special attention to the decoration of the shields of the com- manders who attacked Thebes, relying on two different ways of dec- orating the shields that Homer describes in The Iliad. According to George Henry Chase’s terminology, in Homer, Achilles’ shield can be called “a decorative” shield, and Agamemnon’s shield is referred to as “a terrible” shield. Aeschylus turns the description of the shield decoration of the commanders attacking Thebes into a core element of the plot in Seven against Thebes, maximizing the connection be- tween the image on the shield and the shield-bearer. He created an elaborate system of “terrible” and “decorative” shields (Aesch. Sept. 375-676), as well as of the shields that cannot be categorized as “ter- rible” and “decorative” (Aesch. Sept. 19; 43; 91; 100; 160). The analysis of this system made it possible to put forward and prove three hypothetical assumptions: 1) In Aeschylus, Eteocles demands from the Thebans to win or die, focusing on the fact that the city cre- ated a special educational space for them and raised them as shield- bearers. His patriotic speeches and, later, his judgments expressed in the “shield scene” demonstrate a desire to justify and then test the educational concept “ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς” (“either with it, or upon it”) (Plut. -

Amphitrite - Wiktionary

Amphitrite - Wiktionary https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Amphitrite Amphitrite Definition from Wiktionary, the free dictionary See also: amphitrite Contents 1 Translingual 1.1 Etymology 1.2 Proper noun 1.2.1 Hypernyms 1.3 External links 2 English 2.1 Etymology 2.2 Pronunciation 2.3 Proper noun 2.3.1 Translations Translingual Etymology New Latin , from Ancient Greek Ἀµφιτρίτη ( Amphitrít ē, “mother of Poseidon”), also "three times around", perhaps for the coiled forms specimens take. Amphitrite , unidentified Amphitrite ornata species Proper noun Amphitrite f 1. A taxonomic genus within the family Terebellidae — spaghetti worms, sea-floor-dwelling polychetes. 1 of 2 10/11/2014 5:32 PM Amphitrite - Wiktionary https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Amphitrite Hypernyms (genus ): Animalia - kingdom; Annelida - phylum; Polychaeta - classis; Palpata - subclass; Canalipalpata - order; Terebellida - suborder; Terebellidae - family; Amphitritinae - subfamily External links Terebellidae on Wikipedia. Amphitritinae on Wikispecies. Amphitrite (Terebellidae) on Wikimedia Commons. English Etymology From Ancient Greek Ἀµφιτρίτη ( Amphitrít ē) Pronunciation Amphitrite astronomical (US ) IPA (key): /ˌæm.fɪˈtɹaɪ.ti/ symbol Proper noun Amphitrite 1. (Greek mythology ) A nymph, the wife of Poseidon. 2. (astronomy ) Short for 29 Amphitrite, a main belt asteroid. Translations ±Greek goddess [show ▼] Retrieved from "http://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=Amphitrite&oldid=28879262" Categories: Translingual terms derived from New Latin Translingual terms derived from Ancient Greek Translingual lemmas Translingual proper nouns mul:Taxonomic names (genus) English terms derived from Ancient Greek English lemmas English proper nouns en:Greek deities en:Astronomy en:Asteroids This page was last modified on 27 August 2014, at 03:08. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. -

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique Copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS BY LILIAN STOUGHTON HYDE YESTERDAY’S CLASSICS CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA Cover and arrangement © 2008 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC. Th is edition, fi rst published in 2008 by Yesterday’s Classics, an imprint of Yesterday’s Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by D. C. Heath and Company in 1904. For the complete listing of the books that are published by Yesterday’s Classics, please visit www.yesterdaysclassics.com. Yesterday’s Classics is the publishing arm of the Baldwin Online Children’s Literature Project which presents the complete text of hundreds of classic books for children at www.mainlesson.com. ISBN-10: 1-59915-261-4 ISBN-13: 978-1-59915-261-5 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC PO Box 3418 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 PREFACE In the preparation of this book, the aim has been to present in a manner suited to young readers the Greek myths that have been world favorites through the centuries, and that have in some measure exercised a formative infl uence on literature and the fi ne arts in many countries. While a knowledge of these myths is undoubtedly necessary to a clear understanding of much in literature and the arts, yet it is not for this reason alone that they have been selected; the myths that have appealed to the poets, the painters, and the sculptors for so many ages are the very ones that have the greatest depth of meaning, and that are the most beautiful and the best worth telling. -

Mythology Study Questions

Greek Mythology version 1.0 Notes: These are study questions on Apollodorus’ Library of Greek Mythology. They are best used during or after reading the Library, though many of them can be used independently. In some cases Apollodorus departs from other NJCL sources, and those other sources are more authoritative/likely to come up on tests and in Certamen. In particular, it is wise to read the epics (Iliad, Odyssey, Aeneid, Metamorphoses) for the canonical versions of several stories. Most of these are in question form, and suitable for use as certamen questions, but many of the later questions are in the format of NJCL test questions instead. Students should not be worried by the number of questions here, or the esoteric nature of some of them. Mastering every one of these questions is unnecessary except, perhaps, for those aiming to get a top score on the NJCL Mythology Exam, compete at the highest levels of Certamen, and the like. Further, many of the questions here are part of longer stories; learning a story will often help a student answer several of the questions at once. Apollodorus does an excellent job of presenting stories succinctly and clearly. The best translation of the Library currently available is probably the Oxford Word Classics edition by Robin Hard. That edition is also excellent for its notes, which include crucial information that Apollodorus omits as well as comparisons with other versions of the stories. I am grateful for any corrections, comments, or suggestions. You can contact me at [email protected]. New versions of this list will be posted occasionally. -

![Seven Against Thebes [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8404/seven-against-thebes-pdf-1828404.webp)

Seven Against Thebes [PDF]

AESCHYLUS SEVEN AGAINST THEBES Translated by Ian Johnston Vancouver Island University, Nanaimo, BC, Canada 2012 [Reformatted 2019] This document may be downloaded for personal use. Teachers may distribute it to their students, in whole or in part, in electronic or printed form, without permission and without charge. Performing artists may use the text for public performances and may edit or adapt it to suit their purposes. However, all commercial publication of any part of this translation is prohibited without the permission of the translator. For information please contact Ian Johnston. TRANSLATOR’S NOTE In the following text, the numbers without brackets refer to the English text, and those in square brackets refer to the Greek text. Indented partial lines in the English text are included with the line above in the reckoning. Stage directions and endnotes have been provided by the translator. In this translation, possessives of names ending in -s are usually indicated in the common way (that is, by adding -’s (e.g. Zeus and Zeus’s). This convention adds a syllable to the spoken word (the sound -iz). Sometimes, for metrical reasons, this English text indicates such possession in an alternate manner, with a simple apostrophe. This form of the possessive does not add an extra syllable to the spoken name (e.g., Hermes and Hermes’ are both two-syllable words). BACKGROUND NOTE Aeschylus (c.525 BC to c.456 BC) was one of the three great Greek tragic dramatists whose works have survived. Of his many plays, seven still remain. Aeschylus may have fought against the Persians at Marathon (490 BC), and he did so again at Salamis (480 BC). -

The Aeschylean Concept of the Supreme Deity Joseph Joel Devault Loyola University Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1943 The Aeschylean Concept of the Supreme Deity Joseph Joel Devault Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Devault, Joseph Joel, "The Aeschylean Concept of the Supreme Deity" (1943). Master's Theses. Paper 614. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/614 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1943 Joseph Joel Devault .' THE AESCHl'LEAH CONCEPT OF THE S UPHElvIE DEI TY.. , By Joseph J"oel DeVault, S.J. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilDuent of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Loyola university. March 1943 i VITA Joseph Joel DeVault, S.J., was born in East St. Luuis, Illinois, December 22, 1918. After his elementary edu&ation at st. J&~es's Parochial School, Toleno, Ohio, he attended st. Jo1'..n I s Hie;h School, Toledo, grad uated. therefrom in June,1935, and after one year at st. John I s College entered. tbe Mil ford Novitiate of the Society ~f Jesus, at Milford Ohio, in September, 1936. For the four years he spent there he was academically connected with Xavier University, Ci!lcinnati, Ohio, from which insti tution b,e was graduated wi th the degree of Bachelor of Literature in June, 1940. -

Seven Against Thebes

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 4:2 2018 Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri General Editors Guido Avezzù (Executive Editor), Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editor Francesco Lupi. Editorial Staff Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, Maria Serena Marchesi, Antonietta Provenza, Savina Stevanato. Layout Editor Alex Zanutto. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Daniela Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2018 SKENÈ Published in December 2018 All rights reserved. ISSN 2421-4353 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. SKENÈ Theatre and Drama Studies http://www.skenejournal.it [email protected] Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) Contents Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson Eric Nicholson – Introduction 5 Anton Bierl – The mise en scène of Kingship and Power in 19 Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes: Ritual Performativity or Goos, Cledonomancy, and Catharsis Alessandro Grilli – The Semiotic Basis of Politics 55 in Seven Against Thebes Robert S. -

Greek God Pantheon.Pdf

Zeus Cronos, father of the gods, who gave his name to time, married his sister Rhea, goddess of earth. Now, Cronos had become king of the gods by killing his father Oranos, the First One, and the dying Oranos had prophesied, saying, “You murder me now, and steal my throne — but one of your own Sons twill dethrone you, for crime begets crime.” So Cronos was very careful. One by one, he swallowed his children as they were born; First, three daughters Hestia, Demeter, and Hera; then two sons — Hades and Poseidon. One by one, he swallowed them all. Rhea was furious. She was determined that he should not eat her next child who she felt sure would he a son. When her time came, she crept down the slope of Olympus to a dark place to have her baby. It was a son, and she named him Zeus. She hung a golden cradle from the branches of an olive tree, and put him to sleep there. Then she went back to the top of the mountain. She took a rock and wrapped it in swaddling clothes and held it to her breast, humming a lullaby. Cronos came snorting and bellowing out of his great bed, snatched the bundle from her, and swallowed it, clothes and all. Rhea stole down the mountainside to the swinging golden cradle, and took her son down into the fields. She gave him to a shepherd family to raise, promising that their sheep would never be eaten by wolves. Here Zeus grew to be a beautiful young boy, and Cronos, his father, knew nothing about him. -

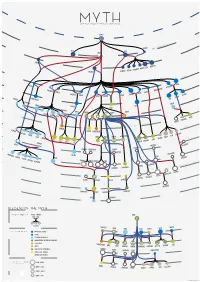

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J.