From the East to the Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Definition of Folklore: a Personal Narrative

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Near Eastern Languages and Departmental Papers (NELC) Civilizations (NELC) 2014 A Definition of olklorF e: A Personal Narrative Dan Ben-Amos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers Part of the Folklore Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Oral History Commons Recommended Citation Ben-Amos, D. (2014). A Definition of olklorF e: A Personal Narrative. Estudis de Literatura Oral Popular (Studies in Oral Folk Literature), 3 9-28. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/141 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/141 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Definition of olklorF e: A Personal Narrative Abstract My definition of folklore as "artistic communication in small groups" was forged in the context of folklore studies of the 1960s, in the discontent with the definitions that were current at the time, and under the influence of anthropology, linguistics - particularly 'the ethnography of speaking' - and Russian formalism. My field esearr ch among the Edo people of Nigeria had a formative impact upon my conception of folklore, when I observed their storytellers, singers, dancers and diviners in performance. The response to the definition was initially negative, or at best ambivalent, but as time passed, it took a more positive turn. Keywords context, communication, definition, performance, -

On Program and Abstracts

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO, CZECH REPUBLIC TENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY TIME AND MYTH: THE TEMPORAL AND THE ETERNAL PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 26-28, 2016 Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic Conference Venue: Filozofická Fakulta Masarykovy University Arne Nováka 1, 60200 Brno PROGRAM THURSDAY, MAY 26 08:30 – 09:00 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:00 – 09:30 OPENING ADDRESSES VÁCLAV BLAŽEK Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA; IACM THURSDAY MORNING SESSION: MYTHOLOGY OF TIME AND CALENDAR CHAIR: VÁCLAV BLAŽEK 09:30 –10:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography & European University, St. Petersburg, Russia OLD WOMAN OF THE WINTER AND OTHER STORIES: NEOLITHIC SURVIVALS? 10:00 – 10:30 WIM VAN BINSBERGEN African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands 'FORTUNATELY HE HAD STEPPED ASIDE JUST IN TIME' 10:30 – 11:00 LOUISE MILNE University of Edinburgh, UK THE TIME OF THE DREAM IN MYTHIC THOUGHT AND CULTURE 11:00 – 11:30 Coffee Break 11:30 – 12:00 GÖSTA GABRIEL Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany THE RHYTHM OF HISTORY – APPROACHING THE TEMPORAL CONCEPT OF THE MYTHO-HISTORIOGRAPHIC SUMERIAN KING LIST 2 12:00 – 12:30 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia CULTIC CALENDAR AND PSYCHOLOGY OF TIME: ELEMENTS OF COMMON SEMANTICS IN EXPLANATORY AND ASTROLOGICAL TEXTS OF ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA 12:30 – 13:00 ATTILA MÁTÉFFY Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey & Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, -

Seven Against Thebes1

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 4:2 2018 Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri General Editors Guido Avezzù (Executive Editor), Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editor Francesco Lupi. Editorial Staff Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, Maria Serena Marchesi, Antonietta Provenza, Savina Stevanato. Layout Editor Alex Zanutto. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Daniela Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2018 SKENÈ Published in December 2018 All rights reserved. ISSN 2421-4353 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. SKENÈ Theatre and Drama Studies http://www.skenejournal.it [email protected] Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) Contents Kin(g)ship and Power Edited by Eric Nicholson Eric Nicholson – Introduction 5 Anton Bierl – The mise en scène of Kingship and Power in 19 Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes: Ritual Performativity or Goos, Cledonomancy, and Catharsis Alessandro Grilli – The Semiotic Basis of Politics 55 in Seven Against Thebes Robert S. -

Lengua Y Cultura Griega III

Materia: Lengua y Cultura Griega III Lenguas y Literaturas Clásicas Cavallero, Pablo Anual - 2016 Programa correspondiente a la carrera de Letras de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Buenos Aires 5 UNIVERSIDAD DE BUENOS AIRES FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y LETRAS ·'· DEPARTAMENTO: Lenguas y literaturas clásicas -'PROFESOR: Pablo Cavallero CUATRIMESTRE: anual AÑO: 2016 PROGRAMANº: 0549 G Aprobado por Resolución Nº 0>.tR.?.?.~.{.1 S --crp;&o/l { M~RTA DE PALMA }- rJ,mctora1 ae Despacho y Afchivo General Universidad de Buenos Aires Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Lenguas y Literaturas Clásicas Asignatura: Lengu~1'8:.1A!V9c~r¡.eg~~ P1td\~"''·' Profesor: Pablo Cavallero · . .. '·· " Cuatrimestre y año: anual, 2016 · Programa Nº: 0549 G 1. Objetivos. Que el alumno logre: * Consolidar la habilidad para traducir textos originales y captar la importancia de esa lectura directa tanto para el análisis literario como para la comprensión del espíritu grie go clásico. * Profundizar el conocimiento de la sintaxis griega. *Valorar y saber comunicar la importancia de las lenguas clásicas como transmisoras, a través de su literatura, de valores humanos trascendentes. * Descubrir en qué grado la cultura griega clásica colaboró en la formación del mundo actual. * Descubrir el influjo dé la lengua, la literatura y la cultura griegas clásicas en los poste riores movimientos artísticos y especialmente en la actualidad. * Valorar el influjo de la lengua griega en la formación del espafiol. * Desarrollar el espíritu crítico para el análisis literario y para reconocer, valorar y dis cutir la bibliografia que aporte consideraciones relevantes. * Iniciar el conocimiento de la métrica clásica. * Conocer los rasgos fundamentales de la retórica clásica a través de textos represen tativos. -

The Shield As Pedagogical Tool in Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes

АНТИЧНОЕ ВОСПИТАНИЕ ВОИНА ЧЕРЕЗ ПРИЗМУ АРХЕОЛОГИИ, ФИЛОЛОГИИ И ИСТОРИИ ПЕДАГОГИКИ THE SHIELD AS PEDAGOGICAL TOOL IN AESCHYLUS’ SEVEN AGAINST THEBES* Victoria K. PICHUGINA The article analyzes the descriptions of warriors in Aeschylus’s tragedy Seven against Thebes that are given in the “shield scene” and determines the pedagogical dimension of this tragedy. Aeschylus pays special attention to the decoration of the shields of the com- manders who attacked Thebes, relying on two different ways of dec- orating the shields that Homer describes in The Iliad. According to George Henry Chase’s terminology, in Homer, Achilles’ shield can be called “a decorative” shield, and Agamemnon’s shield is referred to as “a terrible” shield. Aeschylus turns the description of the shield decoration of the commanders attacking Thebes into a core element of the plot in Seven against Thebes, maximizing the connection be- tween the image on the shield and the shield-bearer. He created an elaborate system of “terrible” and “decorative” shields (Aesch. Sept. 375-676), as well as of the shields that cannot be categorized as “ter- rible” and “decorative” (Aesch. Sept. 19; 43; 91; 100; 160). The analysis of this system made it possible to put forward and prove three hypothetical assumptions: 1) In Aeschylus, Eteocles demands from the Thebans to win or die, focusing on the fact that the city cre- ated a special educational space for them and raised them as shield- bearers. His patriotic speeches and, later, his judgments expressed in the “shield scene” demonstrate a desire to justify and then test the educational concept “ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς” (“either with it, or upon it”) (Plut. -

THE JOHNSONS and THEIR KIN of RANDOLPH

THE JOHNSONS AND THEIR KIN of RANDOLPH JESSIE OWEN SHAW 514 - 19th Street, N.W. Washington 6, D. C. October 15, 1955 Copyright 1955 by Jessie Owen Shaw PRINTED IN USA BY McGREGOR & WERNER. INC. WASHINGTON. b. C. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The compiler desires to express her deep apprecia tion to each one of the many friends whose interest, encour agement and contribution of material have made this book possible. Those deserving particular mention are: Joseph H. Alexander, Selmer, Tenn.; Henry H. Beeson, Dallas, Tex.; Augustine W. Blair, High Point; Mrs. Evelyn Gray Brooks, Warwick, Va.; George D. Finch, Mrs. Eva Leach Hoover and Will R. Owen, Thomasville; Miss Blanche Johnson, Knox ville, Tenn.; the late Miss Emma Johnson, Trinity; Mrs. Myrtle Douglas Loy, Plainfield, Mo.; W. Ernest Merrill, Radford, Va.; John R. Peacock, High Point; Mrs. Erma John son VanWinkle, Clinton, Mo.; the late R. Clark Welborn, Baldwin C it y, Kans.; Mrs. Audrey Stone Williamson, Lexington. iii To the memory of Henry Johnson Who gave his life for American Independence iv PREFACE The historic interest of a place centers in the people, or families who found, occupy and adorn them, and connects them with the stirring legends and important events in the annals of the place. Robert Louis Stevenson spent years tracing his Highland ancestry because he felt that through ancestry one becomes a part of the movement of a country's tradition and history. To be proud of one's ancestry, or to wish to be proud of it, is an almost universal instinct. At a very early age every normal child begins to boast of the superiority of his, or her immediate ancestors to the immediate ancestors of other children. -

Greek God Pantheon.Pdf

Zeus Cronos, father of the gods, who gave his name to time, married his sister Rhea, goddess of earth. Now, Cronos had become king of the gods by killing his father Oranos, the First One, and the dying Oranos had prophesied, saying, “You murder me now, and steal my throne — but one of your own Sons twill dethrone you, for crime begets crime.” So Cronos was very careful. One by one, he swallowed his children as they were born; First, three daughters Hestia, Demeter, and Hera; then two sons — Hades and Poseidon. One by one, he swallowed them all. Rhea was furious. She was determined that he should not eat her next child who she felt sure would he a son. When her time came, she crept down the slope of Olympus to a dark place to have her baby. It was a son, and she named him Zeus. She hung a golden cradle from the branches of an olive tree, and put him to sleep there. Then she went back to the top of the mountain. She took a rock and wrapped it in swaddling clothes and held it to her breast, humming a lullaby. Cronos came snorting and bellowing out of his great bed, snatched the bundle from her, and swallowed it, clothes and all. Rhea stole down the mountainside to the swinging golden cradle, and took her son down into the fields. She gave him to a shepherd family to raise, promising that their sheep would never be eaten by wolves. Here Zeus grew to be a beautiful young boy, and Cronos, his father, knew nothing about him. -

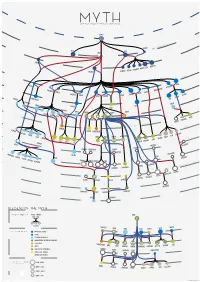

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

Pastiche: Something (Such As a Piece of Writing, Music, Etc.) That Imitates the Style of Someone Or Something Else

English 168, Postmodernism Study Terms For First Tri-Term Exam The majority of the terms you may be asked to define or work with, although others we have reviewed may appear Pastiche: something (such as a piece of writing, music, etc.) that imitates the style of someone or something else. Pastiche is also characteristic of postmodern culture. The Marxist academic Fredric Jameson has examined the functions of postmodern pastiche. He describes pastiche as ‘the random cannibalisation of all the styles of the past, the play of stylistic allusion.’ This is partly the result of over exposure. !n the a"e of mass media there is a sense that #e have seen too many films, #atched too much T%, too much advertisin". &e are over familiar #ith the forms of mass culture, which means it’s impossible to be original. &e can only recycle the conventions of earlier texts ' which Jameson calls the cannibalisation of the past. Jameson describes pastiche as ‘blank parody’. This means that rather than bein" humorous or satirical, pastiche has become a ‘dead lan"ua"e’ unable to satirize in any e*ective #ay. &hereas pastiche used to be a humorous device, it has become ‘devoid of lau"hter’. Subject-position Mytheme/ Bundle of Relations: a mytheme is the essential kernel of a myth—an irreducible, unchanging element,[1] a minimal unit that is always found shared with other, related mythemes and reassembled in various ways ("bundled" was Claude Lévi-Strauss's image)[2] or linked in more complicated relationships. For example, the myths of Adonis and Osiris share several elements, leading some scholars to conclude that they share a source, i.e. -

Independent Agencies, Commissions, Boards

INDEPENDENT AGENCIES, COMMISSIONS, BOARDS ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 809, 20004 phone 606–8503, http://www.achp.gov [Created by Public Law 89–665, as amended] Chairman.—John L. Nau III, Houston, Texas. Vice Chairman.—Bernadette Castro, Albany, New York. Expert Members: Bruce D. Judd, San Francisco, California. Susan S. Schanlaber, Aurora, Illinois. Ann Alexander Pritzlaff, Denver, Colorado. Julia A. King, St. Leonard, Maryland. Citizen Members: Emily Summers, Dallas, Texas. Carolyn J. Brackett, Nashville, Tennessee. Native American Member: Raynard C. Soon, Honolulu, Hawaii. Governor.—Hon. Tim Pawlenty, St. Paul, Minnesota. Mayor.—Hon. Bob Young, Augusta, Georgia. Architect of the Capitol.—Hon. Alan M. Hantman, FAIA. Secretary, Department of: Agriculture.—Hon. Ann M. Veneman. Interior.—Hon. Gale A. Norton. Defense.—Hon. Donald H. Rumsfeld. Transportation.—Hon. Norman Y. Mineta. Administrator: Environmental Protection Agency.—[Vacant]. General Services Administration.—Hon. Stephen A. Perry. National Trust for Historic Preservation.—William B. Hart, Chairman, South Berwick, Maine. National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers.—Edward F. Sanderson, President, Providence, Rhode Island. AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION 1400 Eye Street NW, Suite 1000, 20005–2248, phone 673–3916, fax 673–3810 E-mail: [email protected]; Wb: www.adf.gov [Created by Public Law 96–533] BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman.—Ernest G. Green. Vice Chairman.—Willie Grace Campbell. Private Members: [Vacant]. Public Members: [Vacant]. STAFF President.—Nathaniel Fields. Vice President.—[Vacant]. Advisory Committee Management.—[Vacant]. Congressional Liaison Officer.—Roger Ervin. 763 764 Congressional Directory General Counsel.—Doris Mason Martin. Budget and Finance Director.—Vicki L. Gentry. Management and Information Systems.—Thomas F. Wilson. -

A Review of Contemporary Research on Croatian Mythology in Relation to Natko Nodilo

A REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH ON CROATIAN MYTHOLOGY IN RELATION TO NATKO NODILO SUZANA MARJANIĆ In a review article1 on the subject, I will focus on Natko V preglednem članku se avtorica osredinja na študijo Natka Nodilo’s study Religija (stara vjera) Srba i Hrvata, na glavnoj Nodila Religija (stara vjera) Srba i Hrvata, na glavnoj osnovi pjesama, priča i govora narodnoga (Religion [Old osnovi pjesama, priča i govora narodnoga (Religija Faith] of Serbs and Croats, on the Main Basis of Folk Poems, (stara vera) Srbov in Hrvatov na podlagi ljudskih pesmi, Stories and Narratives) (1885–1890), which is considered the zgodb in pripovedovanja, 1885–1890), ki velja za prvo first reconstruction of Ancient Croatian mythology. Namely, rekonstrukcijo hrvaške mitologije. Vse sodobne raziskave all contemporary research on Croatian mythology/old faith hrvaške mitologije ali starega verovanja namreč delno partially originates from this reconstruction, therefore, I will izhajajo iz te rekonstrukcije, zato avtorica drugi del članka devote the second part of this article to Nodilo’s problem as posveča težavam Nodila kot zgodovinarja, ki se ukvarja z a historian dealing with the interpretations of 19th-century rekonstrukcijo južnoslovanskega starega verovanja, kakor mythophobes regarding the reconstruction of the South so ga interpretirali mitofobi v 19. stoletju.. Slavic old faith. Ključne besede: Natko Nodilo, Vitomir Belaj, Radoslav Keywords: Natko Nodilo, Vitomir Belaj, Radoslav Katičić, Katičić, mitofobi mythophobes The scientific study of myths began in the mid-19th century with the development of com- parative philology, which originated from the idea of a common Indo-European language. Comparative mythology developed from it. Therefore, if there is a common Indo-European language, then there is also a common belief system, specifically in the context of a common belief matrix and, therefore, not in the context of an entire common belief system (cf. -

The Two Voices of Statius: Patronymics in the Thebaid

The Two Voices of Statius: Patronymics in the Thebaid. Kyle Conrau-Lewis This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne, November 2013. 1 This is to certify that: 1. the thesis comprises only my original work towards the degree of master of arts except where indicated in the Preface, 2. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, 3. the thesis is less than 50,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. 2 Contents Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1 24 Chapter 2 53 Chapter 3 87 Conclusion 114 Appendix A 117 Bibliography 121 3 Abstract: This thesis aims to explore the divergent meanings of patronymics in Statius' epic poem, the Thebaid. Statius' use of language has often been characterised as recherché, mannered and allusive and his style is often associated with Alexandrian poetic practice. For this reason, Statius' use of patronymics may be overlooked by commentators as an example of learned obscurantism and deliberate literary self- fashioning as a doctus poeta. In my thesis, I argue that Statius' use of patronymics reflects a tension within the poem about the role and value of genealogy. At times genealogy is an ennobling feature of the hero, affirming his military command or royal authority. At other times, a lineage is perverse as Statius repeatedly plays on the tragedy of generational stigma and the liability of paternity. Sometimes, Statius points to the failure of the son to match the character of his father, and other times he presents characters without fathers and this has implications for how these characters are to be interpreted.