Members Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standards for Superintendents

OHIO Standards For Superintendents Excellence • Commitment • Achievement Members of the 2008 State Board of Education Jennifer Sheets President Heather Heslop Licata Pomeroy Akron Ex Officio Members Jennifer Stewart Robin C. Hovis Senator Joy Padgett Vice President Millersburg Ohio Senate Zanesville Stephen M. Millett Coshocton John R. Bender Columbus Representative Arlene J. Setzer Avon Eric Okerson Ohio House of Representatives Virgil E. Brown, Jr. Cincinnati Vandalia Shaker Heights Emerson J. Ross, Jr. Deborah Cain Toledo Uniontown G. R. “Sam” Schloemer Michael Cochran Cincinnati Blacklick Jane Sonenshein Colleen D. Grady Loveland Strongsville Sue Westendorf Lou Ann Harrold Bowling Green Ada Carl Wick Susan Haverkos Centerville West Chester Ann Womer Benjamin Aurora is document is an official publication of the State Board of Education and the Ohio Department of Education. e information within represents official policy of the State Board. Members of the 2008 State Board of Education Members of the Superintendent Standards Writing Team e members of the superintendent standards writing team included many Ohio superintendents, representing districts statewide – large and small; urban, suburban, and rural. e writing team also included representatives from Ohio’s higher education educational leadership programs, from the Jennifer Sheets Buckeye Association of School Administrators (BASA) to the Ohio Educator Standards Board (ESB), and members currently serving on school President Heather Heslop Licata boards for districts in the state of Ohio. In addition, other Ohio stakeholders were provided with opportunities to review and provide feedback Pomeroy Akron Ex Officio Members during various stages of development of the standards. Jennifer Stewart Robin C. Hovis Senator Joy Padgett Vice President Millersburg Ohio Senate Geoffrey Andrews Ted Kowalski Facilitator Superintendent, Oberlin City Schools University of Dayton Zanesville Stephen M. -

Prayer Practices

Floor Action 5-145 Prayer Practices Legislatures operate with a certain element of pomp, ceremony and procedure that flavor the institution with a unique air of tradition and theatre. The mystique of the opening ceremonies and rituals help to bring order and dignity to the proceedings. One of these opening ceremonies is the offering of a prayer. Use of legislative prayer. The practice of opening legislative sessions with prayer is long- standing. The custom draws its roots from both houses of the British Parliament, which, according to noted parliamentarian Luther Cushing, from time ”immemorial” began each day with a “reading of the prayers.” In the United States, this custom has continued without interruption at the federal level since the first Congress under the Constitution (1789) and for more than a century in many states. Almost all state legislatures still use an opening prayer as part of their tradition and procedure (see table 02-5.50). In the Massachusetts Senate, a prayer is offered at the beginning of floor sessions for special occasions. Although the use of an opening prayer is standard practice, the timing of when the prayer occurs varies (see table 02-5.51). In the majority of legislative bodies, the prayer is offered after the floor session is called to order, but before the opening roll call is taken. Prayers sometimes are given before floor sessions are officially called to order; this is true in the Colorado House, Nebraska Senate and Ohio House. Many chambers vary on who delivers the prayer. Forty-seven chambers allow people other than the designated legislative chaplain or a visiting chaplain to offer the opening prayer (see table 02-5.52). -

“Legislature” and the Elections Clause

Copyright 2015 by Michael T. Morley Vol. 109 Northwestern University Law Review THE INTRATEXTUAL INDEPENDENT “LEGISLATURE” AND THE ELECTIONS CLAUSE Michael T. Morley* INTRODUCTION The Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution is the Swiss army knife of federal election law. Ensconced in Article I, it provides, “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.”1 Its Article II analogue, the Presidential Electors Clause, similarly specifies that “[e]ach State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors” to select the President.2 The concise language of these clauses performs a surprisingly wide range of functions implicating numerous doctrines and fields beyond voting rights, including statutory interpretation,3 state separation of powers and other issues of state constitutional law,4 federal court deference to state-court rulings,5 administrative discretion,6 and preemption.7 * Assistant Professor, Barry University School of Law. Climenko Fellow and Lecturer on Law, Harvard Law School, 2012–14; J.D., Yale Law School, 2003; A.B., Princeton University, 2000. Special thanks to Dr. Ryan Greenwood of the University of Minnesota Law Library, as well as Louis Rosen of the Barry Law School library, for their invaluable assistance in locating historical sources. I also am grateful to Terri Day, Dean Leticia Diaz, Frederick B. Jonassen, Derek Muller, Eang Ngov, Richard Re, Seth Tillman, and Franita Tolson for their comments and suggestions. I was invited to present some of the arguments from this Article in an amicus brief on behalf of the Coolidge-Reagan Foundation in Arizona State Legislature v. -

THE CANVASS: ® States and Election Reform

THE CANVASS: ® States and Election Reform A Newsletter for Legislatures July 2008 Tennessee and Ohio Enact Major Bipartisan Election Reform Inside This Issue Tennessee: Tennessee's legislature recently passed the Tennessee 1 Tennessee and Ohio Voter Confidence Act (House Bill 1256) with strong bipartisan support. Enact Major Election In the House, the bill passed 92-3, and in the Senate it passed Reform unanimously 33-0. The bill was signed into law on June 5, 2008 and follows from recommendations made in a report released earlier this year 5 Statistical Update on by the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. State Election Legislation Sponsored by Representative Gary Moore and Senator Joe Haynes, the bill requires all of the state's counties to convert to precinct-based optical scan 6 Voting Information Project voting by November 2010. It also requires that any voting machine bought or leased after January 1, 2009 be able to create a voter-verified 7 School and Library Safety paper trail, which can be used in recounts and audits. By 2010, all on Election Day counties will have to have voting machines in place that create a paper trail. Importantly, the bill also provides that each election commission 8 Worth Noting: shall conduct mandatory hand count audits of the voter-verified paper ♦ Can Where You Vote ballots of at least the top race in federal, state and local elections. The Affect How You Vote? hand count audits would include 3 percent of the votes cast prior to the ♦ "Top-Two" Primary election by absentee and at in-person early voting sites. -

December 12, 2016 131ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY ENDS LAME DUCK

December 12, 2016 131ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY ENDS LAME DUCK SESSION WITH SEVERAL MUNICIPAL ISSUES ADDRESSED The lame duck session ended Friday morning at about 3:30 am and as the dust settled, we’re proud to report that Ohio municipalities were able to claim a number of victories, a few draws, and only a limited number of losses. Now, we immediately turn our agenda to the next General Assembly, with the release of our first broad based policy report tomorrow. We would like to express our gratitude toward the many members of the General Assembly who worked with us on these many issues. Many members worked with us late into the night many times and worked hard to consider our concerns. Below, we review the legislation that effected municipalities in the final days of the session. Each of the following bills has been sent to Governor Kasich for his consideration. First, is Senate Bill 331, introduced by Senator Bob Peterson (R-Washington Court House). The original bill would regulate the sale of dogs from pet stores and dog retailers and to require the Director of Agriculture to license pet stores. This bill was introduced to create a statewide regulatory framework for pet breeding. The OML opposed this portion of the bill as an infringement on Home Rule and “single issue rule” problems which is the part of the Ohio Constitution that prohibits the legislature from passing bills with multiple subjects. This bill became a “Christmas tree bill” where numerous amendments were added, including language from AT&T on the 5G roll out Amendment 1: As mentioned above and as many of our members are aware, the House Finance committee amended the bill to create new regulations concerning micro wireless facility operators for their use of municipally owned land. -

State Senator Niraj Antani Is Serving His First Term in the Ohio Senate. He Represents the 6Th District, Which Covers Most of Montgomery County

State Senator Niraj Antani is serving his first term in the Ohio Senate. He represents the 6th District, which covers most of Montgomery County. Having been first elected to the Ohio House at age 23, now age 29, he is the youngest currently serving member of the Senate. He is the first Indian American State Senator in Ohio history. From 2014-2020, he served as the State Representative for the 42nd House District in the Ohio House of Representatives. He was the second Indian- American state elected official in Ohio history, and the first Indian-American Republican. While in the House, Antani served as Vice Chairman of the Rules and Reference Committee and as Vice Chairman of the Committee on Insurance, and as a member of the Committee on Health, Committee on Public Utilities, and Joint Medicaid Oversight Committee. During the Romney for President campaign in 2012, Antani worked for the Ohio State Director & Senior Adviser to the campaign. He has also worked for U.S. Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen in Washington, DC, as well as U.S. Congressman Mike Turner in his Dayton office. Antani was named to Forbes Magazine's list of the top "30 Under 30" people in the United States for Law & Politics in 2015. As well, the conservative media organization Newsmax named him the 2nd most influential Republican in the nation under age 30. In addition, in 2013 he was named to the "Top 30 Conservatives Under Age 30 in the United States" list by Red Alert Politics. Antani has received the Legislator of the Year Award by the AMVETS Department of Ohio for his work helping veterans, as well as the Friend of Community Colleges Award by the Ohio Association of Community College and the Distinguished Government Service Award by the Ohio Association of Career Colleges and Schools for his work for the betterment of higher education for the middle class. -

Guide to State Statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection

U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER GUide To STATe STATUes iN The NATioNAl STATUArY HAll CollecTioN CVC 19-107 Edition V Senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii addresses a group of high school students gathered in front of the statue of King Kamehameha in the Capitol Visitor Center. TOM FONTANA U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER GUide To STATe STATUes iN The NATioNAl STATUArY HAll CollecTioN STATE PAGE STATE PAGE Alabama . 3 Montana . .28 Alaska . 4 Nebraska . .29 Arizona . .5 Nevada . 30 Arkansas . 6 New Hampshire . .31 California . .7 New Jersey . 32 Colorado . 8 New Mexico . 33 Connecticut . 9 New York . .34 Delaware . .10 North Carolina . 35 Florida . .11 North Dakota . .36 Georgia . 12 Ohio . 37 Hawaii . .13 Oklahoma . 38 Idaho . 14 Oregon . 39 Illinois . .15 Pennsylvania . 40 Indiana . 16 Rhode Island . 41 Iowa . .17 South Carolina . 42 Kansas . .18 South Dakota . .43 Kentucky . .19 Tennessee . 44 Louisiana . .20 Texas . 45 Maine . .21 Utah . 46 Maryland . .22 Vermont . .47 Massachusetts . .23 Virginia . 48 Michigan . .24 Washington . .49 Minnesota . 25 West Virginia . 50 Mississippi . 26 Wisconsin . 51 Missouri . .27 Wyoming . .52 Statue photography by Architect of the Capitol The Guide to State Statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection is available as a free mobile app via the iTunes app store or Google play. 2 GUIDE TO STATE STATUES IN THE NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER AlabaMa he National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is comprised of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. The entire collection now consists of 100 statues contributed by 50 states. -

The Impact of Race Upon Legislators' Policy Preferences and Bill

THE IMPACT OF RACE UPON LEGISLATORS’ POLICY PREFERENCES AND BILL SPONSORSHIP PATTERNS: THE CASE OF OHIO DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Linda M. Trautman, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor William E. Nelson, Jr., Adviser Professor Tom Nelson ________________________ Adviser Professor Herbert Weisberg Political Science Graduate Program Copyright Linda M. Trautman 2007 ABSTRACT The principal purpose of this research is to explain and to analyze the policy preferences of Black and White state legislators in the Ohio General Assembly. In particular, the study seeks to understand whether or not Black state legislators advocate a distinctive policy agenda through an analysis of their policy preferences and bill sponsorship patterns. Essentially, one of the central objectives of the study is to determine the extent to which legislators’ perceptions of their policy preferences actually correspond with their legislative behavior (i.e., bill sponsorship patterns). In addition to understanding the impact of race upon legislative preferences, I also analyze additional factors (e.g., institutional features, district characteristics, etc.) which potentially influence legislators’ policy preferences and legislative behavior. The data for this inquiry derive from personal interviews with members of the Ohio legislature conducted in the early to late 1990’s and legislative bills introduced in the 1998-1999 session. The analyses of these data suggest that Black state legislators exhibit distinctive agenda setting behavior measured in terms of their policy priorities and bill sponsorship patterns in comparison to White state legislators. -

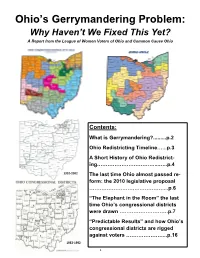

Ohio's Gerrymandering Problem

Ohio’s Gerrymandering Problem: Why Haven’t We Fixed This Yet? A Report from the League of Women Voters of Ohio and Common Cause Ohio Contents: What is Gerrymandering?.........p.2 Ohio Redistricting Timeline…...p.3 A Short History of Ohio Redistrict- ing……………………………...…..p.4 1992-2002 The last time Ohio almost passed re- form: the 2010 legislative proposal ……………………….……………...p.6 “The Elephant in the Room” the last time Ohio’s congressional districts were drawn ……………………….p.7 “Predictable Results” and how Ohio’s congressional districts are rigged against voters …………………...p.16 1982-1992 1 What is Gerrymandering? Redistricting 101: Why do we redraw districts? • Every ten years the US Census is conducted to measure population changes. • The US Supreme Court has said all legislative districts should have roughly the same population so that everyone’s vote counts equally. This is commonly referred to as “one person, one vote.” • In the year following the Census, districts are redrawn to account for people moving into or out of an area and adjusted so that districts again have equal population and, for US House districts, may change depending on the number of districts Ohio is entitled to have. • While the total number of state general assembly districts is fixed -- 99 Ohio House and 33 Ohio Senate districts -- the number of US House districts allocated to each state may change follow- ing the US Census depending on that state’s proportion of the total US population. For example, following the 2010 Census, Ohio lost two US House seats, going from 18 US House seats in 2002-2012 to 16 seats in 2012-2022. -

50 State Report Card Tracking Eminent Domain Reform

50state report card Tracking Eminent Domain Reform Legislation since Kelo August 2007 1 Synopsis 5 Alabama . .B+ 6 Alaska . .D 7 Arizona . .B+ 8 Arkansas . .F 9 California . .D- 10 Colorado . .C 11 Connecticut . .D 12 Delaware . .D- 13 Florida . .A 14 Georgia . .B+ 15 Hawaii . .F 16 Idaho . .D+ 17 Illinois . .D+ 18 Indiana . .B 19 Iowa . .B- 20 Kansas . .B 21 Kentucky . .D+ 22 Louisiana . .B 23 Maine . .D+ 24 Maryland . .D 25 Massachusetts . .F 26 Michigan . .A- 27 Minnesota . .B- 28 Mississippi . .F 29 Missouri . .D table of contents & state grades 30 Montana . .D 31 Nebraska . .D+ 32 Nevada . .B+ 33 New Hampshire . .B+ 34 New Jersey . .F 35 New Mexico . .A- 36 New York . .F 37 North Carolina . .C- 38 North Dakota . .A 39 Ohio . .D 40 Oklahoma . .F 41 Oregon . .B+ 42 Pennsylvania . .B- 43 Rhode Island . .F 44 South Carolina . .B+ 45 South Dakota . .A 46 Tennessee . .D- 47 Texas . .C- 48 Utah . .B 49 Vermont . .D- 50 Virginia . .B+ 51 Washington . .C- 52 West Virginia . .C- 53 Wisconsin . .C+ 54 Wyoming . .B 50state50 reportstate card reportTracking Eminentcard Domain Tracking ReformEminent Legislation Domain since Kelo Abuse Legislation since Kelo I n the two years since the U.S. Supreme Court’s now-infamous decision in Kelo v. City of New London, 42 states have passed new laws aimed at curbing the abuse of eminent domain for private use. 50state report card Castle Coalition Given that significant reform on most issues takes years to accomplish, the horrible state of most eminent domain laws, and that the defenders of eminent domain abuse—cities, developers and planners—have flexed their considerable political muscle to preserve the status quo, this is a remarkable and historic response to the most reviled Supreme Court decision of our time. -

The New York State Legislative Process: an Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform

THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: AN EVALUATION AND BLUEPRINT FOR REFORM JEREMY M. CREELAN & LAURA M. MOULTON BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: AN EVALUATION AND BLUEPRINT FOR REFORM JEREMY M. CREELAN & LAURA M. MOULTON BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW www.brennancenter.org Six years of experience have taught me that in every case the reason for the failures of good legislation in the public interest and the passage of ineffective and abortive legislation can be traced directly to the rules. New York State Senator George F. Thompson Thompson Asks Aid for Senate Reform New York Times, Dec. 23, 1918 Some day a legislative leadership with a sense of humor will push through both houses resolutions calling for the abolition of their own legislative bodies and the speedy execution of the members. If read in the usual mumbling tone by the clerk and voted on in the usual uninquiring manner, the resolution will be adopted unanimously. Warren Moscow Politics in the Empire State (Alfred A. Knopf 1948) The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law unites thinkers and advocates in pursuit of a vision of inclusive and effective democracy. Our mission is to develop and implement an innovative, nonpartisan agenda of scholarship, public education, and legal action that promotes equality and human dignity, while safeguarding fundamental freedoms. The Center operates in the areas of Democracy, Poverty, and Criminal Justice. Copyright 2004 by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report represents the extensive work and dedication of many people. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing fi’om left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microlilms International A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.761-4700 800,521-0600 Order Number 9130556 The development of the Black Elected Democrats of Ohio (BEDO) into a viable state legislative caucus Simms-Maddox, Margaret J., Ph.D.