Publication01-02 2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell

Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell Roger Bushell is famously remembered as “Big X”, the mastermind and driving force behind what is arguably the most audacious prisoner of war escape of the Second World War. The story of the breakout later became immortalized on film in “The Great Escape”, based on the best-selling book of the same name by fellow prisoner, Paul Brickhill. This has largely overshadowed other aspects of his life, his pre-war flying experiences and his, albeit, short wartime role within the RAF. Roger Joyce Bushell was born in 1910 in South Africa to an English gold- mining engineer. At the age of 10 he was sent to boarding school at Wellington in England. Following this he spent time at Grenoble University, becoming a proficient linguist in French and German before going to Cambridge in 1929. Whilst there, he indulged in his non-academic passions including acting, rugby and skiing. It was also whilst at Cambridge that Bushell took up his other great passion: flying. In 1932 he joined 601 Squadron Auxiliary Air Force as a Pilot Officer. 601 Squadron was otherwise known as “The Millionaires’ Squadron” because most of its members were wealthy young men, paying their way to learn how to fly at the weekend. Many of these men were also fellow skiers, such as Max Aitken, who joined the squadron in 1934 following some encouragement from Bushell. Bushell won his wings in June 1933 and was promoted to the rank of Flying Officer 8 months later. On graduating from Cambridge with a law degree, Bushell was called to the Bar in 1934. -

Australian Radio Series

Radio Series Collection Guide1 Australian Radio Series 1930s to 1970s A guide to ScreenSound Australia’s holdings 1 Radio Series Collection Guide2 Copyright 1998 National Film and Sound Archive All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. First published 1998 ScreenSound Australia McCoy Circuit, Acton ACT 2600 GPO Box 2002, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone (02) 6248 2000 Fax (02) 6248 2165 E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.screensound.gov.au ISSN: Cover design by MA@D Communication 2 Radio Series Collection Guide3 Contents Foreword i Introduction iii How to use this guide iv How to access collection material vi Radio Series listing 1 - Reference sources Index 3 Radio Series Collection Guide4 Foreword By Richard Lane* Radio serials in Australia date back to the 1930s, when Fred and Maggie Everybody, Coronets of England, The March of Time and the inimitable Yes, What? featured on wireless sets across the nation. Many of Australia’s greatest radio serials were produced during the 1940s. Among those listed in this guide are the Sunday night one-hour plays - The Lux Radio Theatre and The Macquarie Radio Theatre (becoming the Caltex Theatre after 1947); the many Jack Davey Shows, and The Bob Dyer Show; the Colgate Palmolive variety extravaganzas, headed by Calling the Stars, The Youth Show and McCackie Mansion, which starred the outrageously funny Mo (Roy Rene). Fine drama programs produced in Sydney in the 1940s included The Library of the Air and Max Afford's serial Hagen's Circus. Among the comedy programs listed from this decade are the George Wallace Shows, and Mrs 'Obbs with its hilariously garbled language. -

Noticeboard 2017.3

Lane Cove Historical1 Society Inc. NOTICEBOARD MAY 2017 MONTHLY MEETING TUESDAY 23 MAY Stephen Dando-Collins SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER AAwwaarrrdd wwiiinnnniiinngg aauuttthhoorrr The Hero maker Stephen Stephen Our May 23 Speaker will be Stephen Dando-Collins, an Dando-Colllliins award winning author, biographer, novelist and Dando-Collins children's author who has written on a wide variety of The story of topics from history as well as biographies and research Paul Brickhill, the on WWI and WWII. His latest book, The Hero Maker, is a Greenwich boy whose life biography of Greenwich local, Paul Jerome Chester was as legendary as the Brickhill. legendary stories he created In The Hero Maker, Dando-Collins exposes the contradictions of one of Australia’s most successful, but Tuesday troubled, writers. Brickhill’s extraordinary story—from 23 May the youth with a debilitating stutter to newspaper journalist, to Spitfire pilot and POW, to feted author— 7pm Lane Cove Library!Supper afterwards explodes vividly to life on the centenary of Brickhill's birth. Paul Brickhill and his family lived in Greenwich at 8 Mitchell, then Greendale Street and then at 44 George All visitors welcome; join us and bring your friends to Street. He attended North Sydney Boys High and hear this popular author in Sydney Sydney University. Dropping out of university, Paul's speaking at the Writers' Festival. friend and neighbour, Peter Finch, got him his first job as a copy boy for The Sun newspaper. CCHHEEEESSEE,, WWII NNEE AANNDD JJAAZZZZ SSuunnddaayy 2255 JJuunnee 33--55ppmm $$2255 inclusive inclusive Carisbrook Historic House 334 Burns Bay Road Book now: trybookings https://www.trybooking.com/276387 Enquiries phone 0418 276 365 2 His address, after World War II, was ‘Blytheswood’, government-owned bank. -

![The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4167/the-great-escape-by-paul-brickhill-pdf-3424167.webp)

The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill [PDF]

The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill Ebook The Great Escape currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Great Escape please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback: 304 pages Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company; Reissue edition (August 17, 2004) Language: English ISBN-10: 0393325792 ISBN-13: 978-0393325799 Product Dimensions:5.6 x 0.8 x 8.3 inches ISBN10 0393325792 ISBN13 978-0393325 Download here >> Description: A tense, thrilling, fabulous tale.―Philadelphia InquirerThey were American and British air force officers in a German prison camp. With only their bare hands and the crudest of homemade tools, they sank shafts, forged passports, faked weapons, and tailored German uniforms and civilian clothes. They developed a fantastic security system to protect themselves from German surveillance. It was a split-second operation as delicate and as deadly as a time bomb. It demanded the concentrated devotion and vigilance of more than six hundred men―every one of them, every minute, every hour, every day and night for more than a year. Made into the classic movie starring Steve McQueen. 16 pages of photographs Australian Paul Brickhill, a Spitfire pilot who flew in World War Ii in RAFs 92 Squadron, and that was shot down and taken prisoner in Tunisia in 1943, wrote three famous books in his career after the war: REACH FOR THE SKY (the Douglas Bader history), THE DAM BUSTERS (about RAFs 617 Squadron and the raids against the German dams in the Ruhr), and THE GREAT ESCAPE (about the famous escape from a German Air Force personnel prisoner camp in Sagan).Although all three were made into movies, THE GREAT ESCAPE is by far the most well known, basically due to the fact that it received the full Hollywwod treatment (for better or for worse), in the film of the same name released in 1963. -

A Genius for Deception.Pdf

A Genius for Deception This page intentionally left blank A GENIUS FOR DECEPTION How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars nicholas rankin 1 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2008 by Nicholas Rankin First published in Great Britain as Churchill’s Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, 1914–1945 in 2008 by Faber and Faber, Ltd. First published in the United States in 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rankin, Nicholas, 1950– A genius for deception : how cunning helped the British win two world wars / Nicholas Rankin. p. cm. — (Churchill’s wizards) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-538704-9 1. Deception (Military science)—History—20th century. 2. World War, 1914–1918—Deception—Great Britain. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Deception—Great Britain. 4. Strategy—History—20th century. -

Aviation Paperbacks 1954

Aviation Paperbacks 1954 that the British forces ever possessed; for sheer valour it was unsurpassed - its members won 1954 two Victoria Crosses and over 150 other decorations. This book realistically portrays all 54/hoy.1 Hodder & Stoughton the grimness of air warfare, but also tells of Yellow Jacket humorous episodes and of the disappointments Biggles’ Second Case, [illus.] Captain W.E. when theories and plans were upset. It has just Johns been filmed, with Richard Todd and Michael First published April 1948. Fourth impression Redgrave in leading parts; the script is by R.C. January 1952. This edition (reset) 1954 Sherriff. [Hodder and Stoughton, London]. pp. [vi] [7] Paul Brickhill, an Australian born at 8-192 Melbourne and educated at Sydney, was for Printers: Hazell, Watson and Viney Ltd, five years a fighter-pilot in the Royal Aylesbury and London Australian Air Force. His aircraft was shot Price: 2/- down over Tunisia in 1943; wounded, he baled Front cover: yellow paper, col. Illus. of out, landed in a minefield, and was captured. unidentified seaplane over a submarine When a prisoner, he was active on “X” escape Rear cover: yellow paper, advert. For Teach organisation. After the War he worked as a Yourself Books journalist in London, New York, and Central Notes: pp. [i-ii] half title and review quotes Europe, and wrote a number of war books which have achieved huge sales. He has now 54/pan.1 Pan GP23 returned to Australia. His Escape - or Die is The Dam Busters, Paul Brickhill, with also a Pan Book. foreword by Marshal of the R.A.F. -

Leadership of Australian Pows in the Second World War

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2015 Leadership of Australian POWs in the Second World War Katie Lisa Meale University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Meale, Katie Lisa, Leadership of Australian POWs in the Second World War, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2015. -

CLASSIC HIGHLIGHTS Contents

Autumn 2017 CLASSIC HIGHLIGHTS Contents For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Centenary Celebrations 2018 p. 4 Hollywood adaptations pp. 5-12 Animals pp. 13-18 Troublesome Women pp. 19-24 Agents US Rights: Georgia Glover; Toby Eady, Andrew Gordon Film & TV Rights: Nicky Lund; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights: Alice Howe: [email protected] Giulia Bernabè: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Croatia; Estonia; France; Germany; Greece; Israel; Latvia; Lithuania; Netherlands; Scandinavia; Slovenia; Spain and Spanish in Latin America; Sub-agented: Czech Republic; Italy; Poland; Romania; Slovakia; Turkey Emily Randle: [email protected] Direct: Afrikaans; Albanian; all Indian languages; Brazil; Macedonia; Portugual; Russia; Ukraine; Vietnam; Wales; plus miscellaneous requests Subagented: China; Bulgaria; Hungary; Indonesia; Japan; Korea; Serbia; Taiwan; Thailand Allison Cole: [email protected] Children’s titles in all languages Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk CENTENARY CELEBRATIONS MURIEL SPARK 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of classic writer, Dame Muriel Spark Born in Edinburgh in 1918, Muriel Spark originally worked as a secretary and then a poet and literary journalist. She was completely unknown and impoverished until she started her career as a story writer and novelist. Then everything changed overnight. A poet and novelist, she also wrote children’s books, radio plays, a comedy Doctors of Philosophy, (first performed in London in 1962 and published 1963) and biographies of nineteenth-century literary figures, including Mary Shelley and Emily Brontë. -

War Cinema– Or How British Films Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Affluent Society

1 THE PROFESSIONAL OFFICER CLASS IN POST- WAR CINEMA– OR HOW BRITISH FILMS LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Andrew Roberts College of Business, Arts and Social Sciences of Brunel University 22nd September2014 2 ABSTRACT My central argument is that mainstream British cinema of the 1951 – 1965 period marked the end of the paternalism, as exemplified by a professional ‘officer class’, as consumerism gradually came to be perceived as the norm as opposed to a post-war enemy. The starting point is 1951, the year of the Conservative victory in the General Election and a time which most films were still locally funded. The closing point is 1965, by which point the vast majority of British films were funded by the USA and often featured a youthful and proudly affluent hero. Thus, this fourteen year describes how British cinema moved away from the People as Hero guided by middle class professionals in the face of consumerism. Over the course of this work, I will analyse the creation of the archetypes of post-war films and detail how the impact of consumerism and increased Hollywood involvement in the UK film industry affected their personae. However, parallel with this apparently linear process were those films that questioned or attacked the wartime consensus model. As memories of the war receded, and the Rank/ABPC studio model collapsed, there was an increasing sense of deracination across a variety of popular British cinematic genres. From the beginning of our period there is a number films that infer that the “Myth of the Blitz”, as developed in a cinematic sense, was just that and our period ends with films that convey a sense of a fragmenting society. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Owen, Robert Considered policy or haphazard evolution? No. 617 Squadron RAF 1943 - 45 Original Citation Owen, Robert (2014) Considered policy or haphazard evolution? No. 617 Squadron RAF 1943 - 45. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/25017/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ CONSIDERED POLICY OR HAPHAZARD EVOLUTION? NO. 617 SQUADRON RAF 1943-45 ROBERT MALCOLM OWEN A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield (in collaboration with the Royal Air Force Museum) OCTOBER 2014 2 Copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

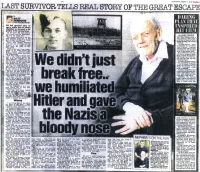

11He1 Great Escape

vveonesoay, August,~. ~uu~ t:-"J, Ii 1, ' . STORJY OF '11HE1' GREAT ESCAPE' By MAff· - BENDOAIS CHlEF FEATURE WRITER THE frail pensioner takes an . age to s~uffl~ from his e1ectric wheelchaar to the bench in the gardens of his nursi.ng hQmeM · . At 96 years old Jack Harri son's body may be deteriorat ing, but his mind isn't. By MARC. DEANIE The former R-AF pHot is the la~t THE Great Escape was a man standing from ene of tt\ie mass attempt by Allied prison mast famous incidents a'f WorM ers of war to break out of the · War II - The. Gr.eat Escape. imposing Stalag Luft Ill camp · That's when inmates tunneMed in Poland. their way out of Stalag Luft III The bleak fortress - which prisoner of war camp in I9'44 is translated as 'permanent right' under the noses oi t'he1r Nazi guards. • camp for airmen' - had been Their actions were later immor opened in April 1942 and was talised . in the screen elassic 'Ehe · considered by the Germans Great Escape starring · Stev~ to be virtually escape proof. M~Queen, James Garner and Rich But on March 24, 1944, 200 ard Attenborough. men led by squadron leader -And since Jack's com,rade Alt',X 'Roger Bushell attempted to L.ees - wha helped scaUer dirt flee through one of the tun dug from the tunneb itn the nels they had dug, that was camp's gardens - passed away ear nicknamed Harry. · lier this year, Ha.rrison is now £fie At 4.45am-the next morning only survivor. -

Special Guest Speaker Award Winning Author Stephen Dando-Collins

SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER AWARD WINNING AUTHOR STEPHEN DANDO-COLLINS Our May 23 Speaker will be Stephen Dando-Collins, an award winning author, biographer, novelist and children's author who has written on a wide variety of topics from ancient history to American, British, French and Australian histories and biography and research on WWI and WWII. His latest book, The Heromaker, is a biography of Greenwich local, Paul Brickhill. In The Hero Maker , Dando-Collins exposes the contradictions of one of Australia’s most successful, but troubled, writers. Brickhill’s extraordinary story – from the youth with a debilitating stutter to Sydney Sun journalist to Spitfire pilot and POW to feted author – explodes vividly to life on the centenary of his birth. PAUL BRICKHILL : Paul Jerome Chester Brickhill and his family lived in Greenwich at 8 Mitchell, then Greendale Street and then at 44 George Street. Paul attended North Sydney Boys High and Sydney University. Dropping out of university, his friend and neighbour Peter Finch, got him his first job as copy boy for The Sun . Paul’s address post-WWII was ‘Blytheswood’ 1 Serpentine St, Greenwich. From there he forged a new career writing of his extraordinary wartime experiences. An "exceptional journalist", Paul Jerome Brickhill became a Spitfire pilot in the RAF. He flew 34 sorties, flying 65 hours, before being shot down. Brickhill's experiences in German POW camps became the basis for his books, which have sold more than five million copies in 17 different languages. By 1954 Paul Brickhill, "the most successful author in Britain", had earned ₤115,000 from his books.