The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See Resource File

Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh (Global Partnership in Attainment of the SDGs) General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh September 2019 Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh Published by: General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Website: www.plancomm.gov.bd First Published: September 2019 Editor: Dr. Shamsul Alam, Member (Senior Secretary), GED Printed By: Inteshar Printers 217/A, Fokirapool, Motijheel, Dhaka. Cell: +88 01921-440444 Copies Printed: 1000 ii Bangladesh Planning Commission Message I would like to congratulate General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission for conducting an insightful study on “Prospect and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh” – an analytical study in the field international cooperation for attaining SDGs in Bangladesh. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda is an ambitious development agenda, which can’t be achieved in isolation. It aims to end poverty, hunger and inequality; act on climate change and the environment; care for people and the planet; and build strong institutions and partnerships. The underlying core slogan is ‘No One Is Left Behind!’ So, attaining the SDGs would be a challenging task, particularly mobilizing adequate resources for their implementation in a timely manner. Apart from the common challenges such as inadequate data, inadequate tax collection, inadequate FDI, insufficient private investment, there are other unique and emerging challenges that stem from the challenges of graduation from LDC by 2024 which would limit preferential benefits that Bangladesh have been enjoying so far. -

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC State Party: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Contact Information: Submitted By: Child Rights Advocacy Save the Children in Coalition in Bangladesh Bangladesh House-82, Road- 19A, Block-E, Banani Dhaka, Bangladesh Tel: +88-02-9861690, Fax: +88-02-9886372 Web: www.savethechildren.net 30th October 2014 Table of Contents PART I: GENERAL OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1 Background and Context ............................................................................................................................. 1 Objective of the Alternative Report ............................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Organization of the Alternative Report ...................................................................................................... 1 PART II: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UNCRC IN BANGLADESH ........................................................ 2 3.3 Rights of children with disabilities and children belonging to minorities........................................ 8 4.3 Freedom of expression and right to seek, receive and impart information ................................. 11 4.4 Freedom of association and peaceful assembly............................................................................ -

Prevalence of Sub-Clinical Mastitis at Banaripara Upazilla, Barisal D

Bangl. J. Vet. Med. (2017). 15 (1): 21-26 ISSN: 1729-7893 (Print), 2308-0922 (Online) PREVALENCE OF SUB-CLINICAL MASTITIS AT BANARIPARA UPAZILLA, BARISAL D. Biswas* and T. Sarker Department of Medicine, Surgery and Obstetrics, Faculty of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Babugonj Campus, Barisal-8210, Bangladesh. ABSTRACT A study was aimed to determine the prevalence of sub-clinical mastitis and also determine the other risk factors that intensify this condition. Prescribed questionnaire was used to take baseline information of the animals and farms and California mastitis test kit was used to determine the SCM in lactating cow at farm level. It appears from this study that an overall prevalence of SCM was 51.56% in milking cows at Banaripara Upazilla, Barisal. Crossbred cows were significantly affected with SCM than local breed lactating cows. The farm type affect significantly (p<0.05) on the occurrence of this diseases. The prevalence of sub-clinical mastitis in cow was significantly (p<0.05) higher in 3 rd (80%) parity compared to 1st (38.09%) and 2rd (45.83%) parity as well as non pregnant cows (55.55%) are more prone to infection than pregnant cow (46.43%). The farm floor condition and aged cows don’t have any effect on SCM. Prevalence of sub-clinical mastitis was significantly (p<0.05) higher in high yielding (87.5%) cows than medium (70%) to low (33.33%) yielding cows. A well documented continued research and educational effort is required to increase producer awareness of cost due to mastitis to the dairy enterprise. -

Assessing of Farmers' Opinion Towards Floating Agriculture As a Means of Cleaner Production

British Journal of Applied Science & Technology 20(6): 1-14, 2017; Article no.BJAST.33635 ISSN: 2231-0843, NLM ID: 101664541 Assessing of Farmers’ Opinion towards Floating Agriculture as a Means of Cleaner Production: A Case of Barisal District, Bangladesh Shaikh Shamim Hasan 1,2* , Ashek Mohammad 3, Mithun Kumar Ghosh 4 and Md. Ibrahim Khalil 5 1Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University (BSMRAU), Gazipur, Bangladesh. 2Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Datun Road, Beijing, China. 3Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), Gazipur, Bangladesh. 4Exim Bank Agricultural University, Chapainawabganj, Bangladesh. 5Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation (BADC), Dhaka, Bangladesh. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all the authors. In this article, author SSH contributed to the research design, organized the research flow, data analysis and interpretation. Author AM contributed to the data collection and data preparation. Author MKG contributed to the manuscript editing and author MIK contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/BJAST/2017/33635 Editor(s): (1) Teresa De Pilli, University of Foggia, Department of Science of Agriculture of Food of Environment (SAFE), Via Napoli, 25; 71100 Foggia, Italy. Reviewers: (1) Barry Silamana, Institute of Environment and Agricultural Research (INERA), Burkina Faso. (2) I. H. Eririogu, Federal University of Technology, Imo State, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/19079 Received 24 th April 2017 th Original Research Article Accepted 8 May 2017 Published 16 th May 2017 ABSTRACT Aims: Bangladesh, as a low-lying country, is vulnerable to global climate change and affected by floods and water logging. -

Barisal -..:: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics

‡Rjv cwimsL¨vb 2011 ewikvj District Statistics 2011 Barisal June 2013 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH District Statistics 2011 District Statistics 2011 Published in June, 2013 Published by : Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Printed at : Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP) Section, FA & MIS, BBS Cover Design: Chitta Ranjon Ghosh, RDP, BBS ISBN: For further information, please contract: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Parishankhan Bhaban E-27/A, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. www.bbs.gov.bd COMPLIMENTARY This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of the sources. ii District Statistics 2011 Foreword I am delighted to learn that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) has successfully completed the ‘District Statistics 2011’ under Medium-Term Budget Framework (MTBF). The initiative of publishing ‘District Statistics 2011’ has been undertaken considering the importance of district and upazila level data in the process of determining policy, strategy and decision-making. The basic aim of the activity is to publish the various priority statistical information and data relating to all the districts of Bangladesh. The data are collected from various upazilas belonging to a particular district. The Government has been preparing and implementing various short, medium and long term plans and programs of development in all sectors of the country in order to realize the goals of Vision 2021. -

Situation Assessment Report in S-W Coastal Region of Bangladesh

Livelihood Adaptation to Climate Change Project (BGD/01/004/01/99) SITUATION ASSESSMENT REPORT IN S-W COASTAL REGION OF BANGLADESH (JUNE, 2009) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) Acknowledgements The present study on livelihoods adaptation was conducted under the project Livelihood Adaptation to Climate Change, project phase-II (LACC-II), a sub-component of the Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (CDMP), funded by UNDP, EU and DFID which is being implemented by the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) with technical support of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UN. The Project Management Unit is especially thankful to Dr Stephan Baas, Lead Technical Advisor (Environment, Climate Change and Bioenergy Division (NRC), FAO, Rome) and Dr Ramasamy Selvaraju, Environment Officer (NRC Division, FAO, Rome) for their overall technical guidance and highly proactive initiatives. The final document and the development of the project outputs are direct results of their valuable insights received on a regular basis. The inputs in the form of valuable information provided by Field Officers (Monitoring) of four coastal Upazilas proved very useful in compiling the report. The reports of the upazilas are very informative and well presented. In the course of the study, the discussions with a number of DAE officials at central and field level were found insightful. In devising the fieldwork the useful contributions from the DAE field offices in four study upazilas and in district offices of Khulna and Pirojpur was significant. The cooperation with the responsible SAAOs in four upazilas was also highly useful. The finalization of the study report has benefited from the valuable inputs, comments and suggestions received from various agencies such as DAE, Climate Change Cell, SRDI (Central and Regional offices), and others. -

The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh

World Bank Group The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh: Experiences from the Ground World Bank Institute 1 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 3 Story #1: Rezia Khatun used the RTI Act to get a Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) card…………………………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 5 Story #2: Shamima Akter uses the RTI Act to help vulnerable women to access government programs in her village………………………………………………………………………… Pg. 6 Story #3: Jobeda Begum uses information to increase the beneficiaries on a government program………………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 7 Story #4: Rafiqul Islam demands information to bring transparency to the distribution of grains. Pg. 8 Story #5: RTI Act helps in implementing minimum wage in shrimp processing………………... Pg. 9 Story #6: The use of RTI for environmental advocacy against illegal building………………….. Pg. 11 Story #7: Mosharaf Hossain uses the RTI Act to ensure that his online complaint for migrant workers is heard……………………………………………………………………………… Pg. 13 Story #8: Information Commission helps Mosharef Hossain Majhi to access information on agriculture issues…………………………………………………….……………. Pg. 15 Story #9: By using the RTI Act, poor women receive access to maternal health vouchers…….. Pg. 17 Story #10: Landless committees use the RTI Act to gain access to land records……………… Pg. 19 Story #11: RTI Act helps improve the lives of fishermen……………………………………... Pg. 21 Story #12: By using the RTI Act, Mohammad gets access to the Agriculture Input Assistance Card…………………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 23 Story #13: RTI helps to place names on a list of beneficiaries in government program………. Pg. 25 Story #14: Rabidas community utilizes RTI for getting Old Age Pension in Saidpur, Nilphamari. Pg. 26 Story #15: RTI Act enables Munna Das to get information from the youth development officer. -

Storm Surges and Coastal Erosion in Bangladesh - State of the System, Climate Change Impacts and 'Low Regret' Adaptation Measures

Storm surges and coastal erosion in Bangladesh - State of the system, climate change impacts and 'low regret' adaptation measures By: Mohammad Mahtab Hossain Master Thesis Master of Water Resources and Environmental Management at Leibniz Universität Hannover Franzius-Institute of Hydraulic, Waterways and Coastal Engineering, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geodetic Science Advisor: Dipl.-Ing. Knut Kraemer Examiners: Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. T. Schlurmann Dr.-Ing. N. Goseberg Submission date: 13.09.2012 Prof. Dr. Torsten Schlurmann Hannover, Managing Director & Chair 15 March 2012 Franzius-Institute for Hydraulic, Waterways and Coastal Engineering Leibniz Universität Hannover Nienburger Str. 4, 30167 Hannover GERMANY Master thesis description for Mr. Mahtab Hussein Storm surges and coastal erosion in Bangladesh - State of the system, climate change impacts and 'low regret' adaptation measures The effects of global environmental change, including coastal flooding stem- ming from storm surges as well as reduced rainfall in drylands and water scarcity, have detrimental effects on countries and megacities in the costal regions worldwide. Among these, Bangladesh with its capital Dhaka is today widely recognised to be one of the regions most vulnerable to climate change and its triggered associated impacts. Natural hazards that come from increased rainfall, rising sea levels, and tropical cyclones are expected to increase as climate changes, each seri- ously affecting agriculture, water & food security, human health and shelter. It is believed that in the coming decades the rising sea level alone in parallel with more severe and more frequent storm surges and stronger coastal ero- sion will create more than 20 million people to migrate within Bangladesh itself (Black et al., 2011). -

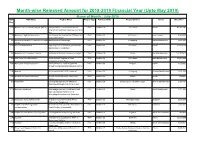

Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg

Month-wise Released Amount for 2018-2019 Financial Year (Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg. 2473 Medicins Sans Frontieres-Belgium (MSFB) Ukhiya the Host Community Outreach FD-6 2018-Jul-26 Cox's Bazar Health 83,062,387 Program and Outbreak Response Coxs bazar Dist 55 Madaripur Legal Aid Association Lets Cleanup the Country Day 2018 and Lets FD-6 2018-Jul-25 All Districts, Environment 6,000,000 Build Green Schools 135 Mohamuni Bidhaba-O-Anath Shishu Kalyan Maintenance of Orphanage FD-6 2018-Jul-22 Chittagong, Social Development 3,032,500 Kendra 2266 Nutrition International Operating Cost of Alleviating Micronutient FD-6 2018-Jul-01 All Districts, Health 45,604,296 Malnutrition in Bangladesh 665 Medecins Sans Frontieres - France Re-Launch of Mission Coordination Project FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Dhaka, Social Development 123,787,691 476 NGO Forum For Public Health WASH Support Program for Host FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Cox's Bazar Local Government 37,867,093 Community in Coxs Bazar 2997 Mafizuddin Nazeda Foundation Rural Community Health Programme FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dinajpur, Health 1,100,000 through Mofizuddin Mazed Medical Centre 1181 Mamata HER Project-MAMATA(HER Finance) FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Chittagong, Women Development 5,691,289 1982 Mosabbir Memorial foundation Strenthening of Mosabbir Cancer Care FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dhaka, Health 834,827 Centre 943 Naripokkho Claiming the Right to Safe Menstrual FD-6 2018-Jul-29 Dhaka, Barisal, Patuakhali, Bogra, Women Development -

Health Minister's National Award 2018

Health Minister’s National Award 2018 Results Background completed by aggregating the scores across different tools for a total of 510 facilities. In 2014, the Management Information System (MIS) The final results of the best performing health unit of the Directorate General of Health Services facilities, community health services, and (DGHS) launched a performance management sub-national health offices in the public sector under initiative for improving health services in the public the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare for 2018 health sector. The initiative is aligned with WHO’s six are presented here. building blocks of health systems1. It has four objectives (Figure 1) and entails measurement of Tools used for assessment performance, ranking and rewarding of health In total, four distinct tools were used, each of which facilities, community health services and sub-national accounts for a specific weighted score with a total of health offices. This has incentivised health managers 100% as demonstrated in Figure 2. Figure 1: Objectives of the health • The first was the online measurement tool where systems strengthening initiative facilities, community health services (through the To establish structured and routine upazila health offices) and sub-national health reporting mechanisms using online tools offices report on selected indicators through the for health facilities; existing systems used in MIS; To regularly measure the performance • The second was an internal evaluation conducted of health facilities and public health by the health managers using the onsite interventions; monitoring tool to review and report on the performance of the facilities and community To score the performance of health facilities annually and rank them for health services under their responsibility; health minister's award; • The third was an external evaluation conducted by a quasi-independent team composed of To promote best practices in health assessors from DGHS and WHO using the physical care management. -

The Millennium Development Goals

The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Progress Report 2009 has been benefited from the financial and technical assistance of the United Nations System in Bangladesh. The Millennium Development Goals The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Design & Published by General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Copies printed: 2500 Printed by Scheme Service Genesis (Pvt.) Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Message Air Vice Marshal (Retd.) A. K. Khandker The Millennium Development Goals Minister Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh I am happy to learn that the General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission has prepared the `Millennium Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2009’ taking inputs from relevant ministries and related stakeholders along with the technical assistance from the UN Systems. As the coming Sixty-fifth session of the United Nations General Assembly, inter alia, will review the latest achievements of the MDGs, the report will be supportive to do the same for Bangladesh The Government of Bangladesh is committed to achieve the MDGs within the given timeframe and accordingly prepared an action plan. The National Strategy for Accelerated Poverty Reduction (NSAPR-1), the Medium Term Budgetary Framework (MTBF) and the Annual Development Programs (ADPs) have also been tuned towards achieving the MDGs. -

Union: College BARISAL BARISAL ALL ALL Institute = ALL for Whom

Name and Address Zone: BARISAL Institute Type = ALL Institute = ALL District: BARISAL Upazilla: ALL For Whom = ALL Union: ALL Mpo Enlisted = N/A Institute College Management Type = ALL RegionType: = All Geographical Location = All Total No. of Institute: 71 SL# DISTRICT THANA INSTITUTE NAME EIIN Address Phone/Mobile EMAIL Updated Date 1 BARISAL AGAILJHAR BASHAIL COLLEGE 136509 Village: BASHAIL Upazila: 0 0 04/05/2017 A AGAILJHARA District: BARISAL Zone: 01715309859 BARISAL 2 BARISAL AGAILJHAR SHAHEED ABDUR ROB 100382 Village: Union: BAKAL 0432356211 02/02/2019 A SERNIABAT DEGREE Upazila: AGAILJHARA District: 01715834843 COLLEGE BARISAL Zone: BARISAL 3 BARISAL BABUGANJ AGARPUR COLLEGE 100440 Village: AGARPUR Union: AGARPUR 01712114360 agarpurcollege@yahoo. 18/11/2018 Upazila: BABUGANJ District: BARISAL com Zone: BARISAL BARISAL BABUGANJ babugonjcollege@gmail 4 BABUGANJ DEGREE 100441 Village: Upazila: BABUGANJ 05/05/2017 COLLEGE .com District: BARISAL Zone: BARISAL 5 BARISAL BABUGANJ GOVT. ABUL KALAM 100442 Village: RAKUDIA Union: DEHERGATI 01762102377 abulkalamdegreecolleg 12/06/2019 COLLEGE, RAKUDIA Upazila: BABUGANJ District: BARISAL [email protected] Zone: BARISAL 6 BARISAL BAKERGON ABUL HOSSAIN KHAN 100599 Village: KRISHNA KATHI Upazila: 01726120410 27/04/2018 J COLLEGE BAKERGONJ District: BARISAL Zone: BARISAL 7 BARISAL BAKERGON AL HAZ HOZROT ALI 100592 Village: KOSHABAR Union: DARIAL 01727725260 10/04/2018 J COLLGE Upazila: BAKERGONJ District: 01727725260 BARISAL Zone: BARISAL 8 BARISAL BAKERGON ATAHAR UDDIN 100588 Village: BALIKATI Upazila: