Aberdeen and Its Hinterland, 1500-1700

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aberdeen Access from the South Core Document

Aberdeen Access from the South Core Document Aberdeen City Council, Aberdeenshire Council, Nestrans Transport Report 69607 SIAS Limited May 2008 69607 TRANSPORT REPORT Description: Aberdeen Access from the South Core Document Author: Julie Sey/Peter Stewart 19 May 2008 SIAS Limited 13 Rose Terrace Perth PH1 5HA UK tel: 01738 621377 fax: 01738 632887 [email protected] www.sias.com i:\10_reporting\draft reports\core document.doc 69607 TRANSPORT REPORT CONTENTS : Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Study Aims 2 1.3 Report Format 2 2 ANALYSIS OF PRESENT AND FUTURE PROBLEMS 3 2.1 Introduction 3 2.2 Geographic Context 3 2.3 Social Context 4 2.4 Economic Context 5 2.5 Strategic Road Network 6 2.6 Local Road Network 7 2.7 Environment 9 2.8 Public Transport 10 2.9 Vehicular Access 13 2.10 Park & Ride Plans 13 2.11 Train Services 14 2.12 Travel Choices 15 2.13 Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (AWPR) 17 2.14 Aberdeen Access from the South Problems Summary 17 3 PLANNING OBJECTIVES 19 3.1 Introduction 19 3.2 Aims 19 3.3 Structure Plans & Local Plans 19 3.4 National Policy 22 3.5 Planning Objective Workshops 23 3.6 Planning Objectives 23 3.7 Checking Objectives are Relevant 25 4 OPTION GENERATION, SIFTING & DEVELOPMENT 27 4.1 Introduction 27 4.2 Option Generation Workshop 27 4.3 Option Sifting 27 4.4 Option and Package Development 28 4.5 Park & Ride 32 5 ABERDEEN SUB AREA MODEL (ASAM3B) ITERATION 33 5.1 Introduction 33 5.2 ASAM3b Development Growth 33 5.3 ASAM3B Influence 33 19 May 2008 69607 6 SHORT TERM OPTION ASSESSMENT 35 6.1 Introduction -

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Alford

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Alford-Haughton Country Park Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This is an easy circular walk with modest overall ascent. Starting and finishing at Alford, an attractive Donside village situated in its own wide and fertile Howe (or Vale), the route passes though parkland, woodland, riverside and farming country, with extensive rural views. Duration: 2.5 hours Route Overview Duration: 2.5 hours. Transport/Parking: Frequent Stagecoach #248 service from Aberdeen. Check timetable. Parking spaces at start/end of walk outside Alford Valley Railway, or nearby. Length: 7.570 km / 4.73 mi Height Gain: 93 meter Height Loss: 93 meter Max Height: 186 meter Min Height: 131 meter Surface: Moderate. Mostly on good paths and paved surfaces. A fair amount of walking on pavements and quiet minor roads. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance. Difficulty: Easy. Dog Friendly: Yes, but keep dogs on lead near to livestock, and on public roads. Refreshments: Options in Alford. Description This is a gentle ramble around and about the attractive large village of Alford, taking in the pleasant environs of Haughton Country Park, a section along the banks of the River Don, and the Murray Park mixed woodland, before circling around to descend into the centre again from woodland above the Dry Ski Slope. Alford lies within the Vale of Alford, tracing the middle reaches of the River Don. In the summer season, the Alford Valley (Narrow-Gauge) Railway, Grampian Transport Museum, Alford Heritage Centre and Craigievar Castle are popular attractions to visit when in the area. -

Schools Are Listed Alphabetically in Associated School Groups. Secondary School Highlighted in Yellow

Schools are listed alphabetically in Associated School Groups. Secondary school highlighted in Yellow NAME & ADDRESS HEAD TEACHER CONTACT DETAILS Aberdeen Grammar School Graham Legge Tel: 01224 642299 Fax: 01224 627413 Skene Street Aberdeen AB10 1HT [email protected] www.grammar.org.uk Ashley Road School Anne Wilkinson Tel: 01224 588732 Fax: 01224 586228 45 Ashley Road Aberdeen AB10 6RU [email protected] www.ashleyroad.aberdeen.sch.uk Gilcomstoun School Stewart Duncan Tel: 01224 642722 Fax: 01224 620784 Skene Street Aberdeen AB10 1PG [email protected] www.gilcomstoun.aberdeen.sch.uk Mile End School Eleanor Sheppard Tel: 01224 498140 Fax: 01224 208758 Midstocket Road Aberdeen AB15 5PD [email protected] www.mileend.aberdeen.sch.uk Skene Square School Eileen Jessamine Tel: 01224 630493 Fax: 01224 620788 61 Skene Square Aberdeen AB25 2UN [email protected] www.skenesquare.aberdeen.sch.uk St Joseph’s RC School Catherine Tominey Tel: 01224 322730 Fax: 01224 325463 5 Queens Road Aberdeen AB15 4YL [email protected] www.stjosephsprimary.aberdeen.sch.uk NAME & ADDRESS HEAD TEACHER CONTACT DETAILS Bridge of Don Academy Daphne McWilliams Tel: 01224 707583 Fax: 01224 706910 Braehead Way Bridge of Don [email protected] Aberdeen AB22 8RR www.bridgeofdon.aberdeen.sch.uk Braehead School Diane Duncan Tel: 01224 702330 Fax: 01224 707659 Braehead Way Bridge of Don [email protected] Aberdeen AB22 8RR www.braehead.aberdeen.sch.uk Scotstown School Caroline Bain Tel: 01224 703331 Fax: 01224 820289 Scotstown Road Bridge of Don [email protected] Aberdeen AB22 8HH www.scotstown.aberdeen.sch.uk Balmedie School Ken McGowan Tel: 01358 742474 Forsyth Road Balmedie [email protected] Aberdeenshire www.balmedie.aberdeenshire.sch.uk AB23 8YW Schools are listed alphabetically in Associated School Groups. -

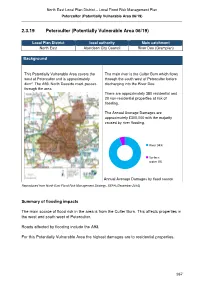

Peterculter (Potentially Vulnerable Area 06/19)

North East Local Plan District – Local Flood Risk Management Plan Peterculter (Potentially Vulnerable Area 06/19) 2.3.19 Peterculter (Potentially Vulnerable Area 06/19) Local Plan District local authority Main catchment North East Aberdeen City Council River Dee (Grampian) Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area covers the The main river is the Culter Burn which flows west of Peterculter and is approximately through the south west of Peterculter before 4km 2. The A93, North Deeside road, passes discharging into the River Dee. through the area. There are approximately 380 residential and 20 non-residential properties at risk of flooding. The Annual Average Damages are approximately £300,000 with the majority caused by river flooding. River 94% Surface water 6% Annual Average Damages by flood source Reproduced from North East Flood Risk Management Strategy, SEPA (December 2015) Summary of flooding impacts The main source of flood risk in the area is from the Culter Burn. This affects properties in the west and south west of Peterculter. Roads affected by flooding include the A93. For this Potentially Vulnerable Area the highest damages are to residential properties. 267 North East Local Plan District – Local Flood Risk Management Plan Peterculter (Potentially Vulnerable Area 06/19) History of flooding In 1827, heavy rainfall caused the failure of several small dams associated with paper milling on the Burn of Culter. This caused extensive damage to agricultural crops and the paper mill. More recently, flooding occurred at North Deeside Road, Craigton Crescent and Buckleburn Place. These incidents were caused by blocked and inadequate drainage systems. On 23 December 2012 around 50 properties were affected by flooding from the Culter Burn. -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Stonehaven-Cowie Chapel Ramble

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Stonehaven-Cowie Chapel Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary The perfect walk to stimulate the senses and blow away the cobwebs, combining a sweeping bay, one of the most picturesque harbours in Scotland, and a breath-taking cliff-top path, with the historical curiosities associated with the Auld Toon of Stonehaven and Cowie Village. Duration: 2.5 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2.5 hours. Transport/Parking: Bus and rail services to Stonehaven. Parking at the harbour in Stonehaven, or on-street nearby. Length: 8.180 km / 5.11 mi Height Gain: 172 meter Height Loss: 172 meter Max Height: 46 meter Min Height: 1 meter Surface: Moderate. Mostly smooth paths or paved surfaces. Section at Cowie cliffs before Waypoint 2 may be muddy. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance and overall ascent. Difficulty: Medium. Dog Friendly: Yes. On lead in built-up areas and public roads. Refreshments: A number of options at Stonehaven harbour and elsewhere in the town. Description This is a very varied walk around and about the coastal town of Stonehaven, sampling its distinctive character and charm. Nestling around a large crescent-shaped bay, the town sits in a sheltered amphitheatre with the quirky Auld Toon close by the impressive and picturesque harbour. A breakwater was first built here in the 16thC and the harbour-side Tolbooth, now a museum, was converted from an earlier grain store in about 1600. The old town lying behind it is full of character and interest. The Ship Inn was built in 1771, predating the unusually-towered Town House which was built in 1790. -

ARO26: the Complex History of a Rural Medieval Building in Kintore, Aberdeenshire by Maureen C

ARO26: The complex history of a rural medieval building in Kintore, Aberdeenshire By Maureen C. Kilpatrick With contributions by Diane Aldritt, Jo McKenzie, George McLeod and Bob Will Archaeology Reports Online, 52 Elderpark Workspace, 100 Elderpark Street, Glasgow, G51 3TR 0141 445 8800 | [email protected] | www.archaeologyreportsonline.com ARO26: The complex history of a rural medieval building in Kintore, Aberdeenshire Published by GUARD Archaeology Ltd, www.archaeologyreportsonline.com Editor Beverley Ballin Smith Design and desktop publishing Gillian Sneddon Produced by GUARD Archaeology Ltd 2017. ISBN: 978-0-9935632-5-6 ISSN: 2052-4064 Requests for permission to reproduce material from an ARO report should be sent to the Editor of ARO, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the ARO Reports series rests with GUARD Archaeology Ltd and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. All rights reserved. GUARD Archaeology Licence number 100050699. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. Contents Abstract 5 Introduction 5 Site Location 5 Archaeological Background 5 Excavation Results 8 The building 8 Structures later than the building 11 Radiocarbon Dates 11 Specialist Reports 12 Pottery 12 Botanical Remains 13 Soil Micromorphology 16 Multi-element Soil Analysis -

Centrepoint Retail Park Aberdeen Ab25 3Sq

NEW LETTING TO CENTREPOINT RETAIL PARK ABERDEEN AB25 3SQ PRIME RETAIL PARK TO THE WEST OF ABERDEEN CITY CENTRE LEASE EXTENSION WITH MECCA 94,376 SQ FT | 8768 SQ M / 600 PARKING SPACES / OPEN PLANNING CONSENT NORTH ELLON A90 G T N 20 MINUTE DRIVE TIME STATS O R CLIFTON RD T NEWMACHAR H E R N R O A D 20 MIN BALMEDIE 20 DRIVE TIME 20 MINUTE DRIVE TIME KITTYBREWSTER P O FOR 250,000 PEOPLE BLACKDOG W RETAIL PARK BLACKBURN DYCE IS T E INVERNESS BACK HILTON RD R R ABERDEEN A C INTERNATIONAL E AIRPORT BEDFORD RD ASHGROVE RD A96 ERSKINE ST ABERDEEN ELMBANK TERRACE POWIS TERRACE A96 58.3% BELMONT RD WESTHILL KINGSWELLS LESLIE TERRACE OF TOTAL HOUSEHOLDS ABERDEEN ARE ABC1 HARBOUR CULTS BIELDSIDE SAINSBURY’S PETERCULTER BERRYDEN ROAD COVE CALSAYSEAT RD POWIS PLACE 42% GEORGE STREET LESLIE TERRACE OF POPULATION AGED AWPR ELM PLACE BETWEEN 20 AND 44 Aberdeen Western YEARS OLD Peripheral Route RAILWAY NETWORK - LINKS TO BERRYDEN ROAD NORTHERN AND CHESNUT ROW SOUTHERN CITIES PORTLETHEN SOUTH A90 BERRYDEN 500,000 LOCATION: RETAIL PARK ABERDEEN’S APPROXIMATE Centrepoint Retail Park is located approximately CATCHMENT POPULATION 1 mile North West of Aberdeen city centre. UNDER OFFER BERRYDEN UNIT 3 RETAIL PARK AVAILABLE 285 6500 SQ FT CAR SPACES CENTREPOINT RETAIL PARK 600 CAR SPACES SAINSBURY’S 276 CAR SPACES SAINSBURY’S [85,000 SQ FT / 7897 SQ M] CENTREPOINT RETAIL PARK [94,376 SQ FT / 8768 SQ M] Mecca Bingo Poundland BERRYDEN RETAIL PARK [73,141 SQ FT / 6795 SQ M] Next Argos Mothercare Currys Contact the joint letting agents to discuss asset management opportunities at Centrepoint. -

Medieval Burgh : Staff, Students Andthegeneral Public

AB DN VisitAberdeen // Weekend Aberdeen Old Town 04 Sports Village 34 Cathedrals 06 AFC 36 Ancestral 08 Satrosphere 38 Universities 10 Transition Extreme 40 //YOUR VISIT Walks + Beach Walks 12 Shopping 42 Parks 14 The Merchant Quarter 44 HMT and Music Hall 16 Whisky 46 Happy to meet, sorry to part, happy Live Events 18 Castles 48 to meet again; that is the official Art Gallery 20 Royal Deeside 50 toast of the city of Aberdeen and Maritime Museum 22 Wildlife 52 one you won’t forget after your Gordon Highlanders 24 Banffshire Coast 54 own visit. From its vibrant nightlife, Harbour 26 Stonehaven 56 historic architecture and abundance Urban Dolphins + 28 Skiing 58 of culture, you’re truly spoilt for Harbour Cruises Food 60 Drink 62 choice in the city. Aberdeen is also :contents Fittie 30 Local Produce 64 Golf 32 packed full of lovely places to stay, Map 66 fantastic restaurants with a range of delicious menus from around the world and fun-filled activities to keep your itinerary thoroughly entertaining. You’ll be safe in the knowledge that Aberdeen’s Visitor Information Centre located on Union Street, is staffed by local experts who are more than willing to help you explore what the city has to offer. Alternatively you can bookmark www.visitaberdeen. com on your phone or download the MyAberdeen mobile app. So what are you waiting for? Enjoy your visit! Steve Harris, Chief Executive 3 //OLD TOWN The history of Aberdeen has Robert The Bruce was Aberdeen’s greatest benefactor always been a tale of two gifting Royal lands to the people in 1319 after they cities, whose modern role helped him repel English invaders. -

Church of Scotland Presbytery of Aberdeen and Shetland

Church of Scotland Presbytery of Aberdeen and Shetland Congregational virtual services and pastoral support during church building closures th as at 5 November 2020 Presbytery of Aberdeen and Shetland website – http://www.aberdeenshetlandpresbytery.org.uk/ or Facebook page – www.facebook.com/aberdeenshetlandpresbytery Please adhere to the Church of Scotland Coronavirus Guidelines if visiting a Church of Scotland building – https://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/resources/covid-19-coronavirus-advice 1 Congregation Additional Information Bridge of Don Oldmachar Parish Church Please contact the congregation if you wish to find out what dates they will hold a physical Sunday service and to book a space. Interim Moderator the Rev Jim Weir - A virtual service should be available. (please contact the church office for contact) https://www.facebook.com/oldmacharchurchpage Building may not be fully open Ashwood Park Please also access the website Bridge of Don https://www.oldmacharchurch.org/ Aberdeen AB22 8PR The congregation are staying in contact with members via email and through [email protected] the Facebook page. It is hoped to set up group meeting’s utilising the ‘Zoom’ 01224 709299 Church Office conferencing facility. In the meanwhile, elders are telephoning and sending messages via email to stay in contact. It is hoped that they will be able to streaming the Little Jammers group on Facebook soon. Bucksburn Stoneywood Parish Church Please contact the congregation if you wish to find out what dates they will hold a physical Sunday service and to book a space. Minister – The Rev Dr Nigel Parker • A virtual service should be available. [email protected] • 01224 712635 A Foodbank collection service is available at the Church Car Park on Friday’s from 10am -12 noon. -

Public Document Pack

Public Document Pack ABERDEEN CITY COUNCIL To : Councillor Reynolds, Convener ; and Councillors Allan, Boulton, Cassie, Clark, Collie, Corall, Crockett, Dunbar, Fletcher, Hunter, Kiddie, Milne, John Stewart and Kristy West. Town House, ABERDEEN, 20 August 2009 LICENSING COMMITTEE The Members of the LICENSING COMMITTEE are requested to meet in Committee Room 2 - Town House on WEDNESDAY, 2 SEPTEMBER 2009 at 10.00 am . Jane MacEachran City solicitor B U S I N E S S 1. Minutes, Committee Business Statement and Informal Business 1.1 Minute of Meeting of 03 June 2009 (Pages 1 - 20) 1.2 Licensing Hearings Sub-Committee- Minute of Meeting of 02 June 2009 (Pages 21 - 22) 1.3 Sports Ground Advisory Working Group - Minute of Meeting of 22 July 2009 (Pages 23 - 24) 1.4 Sports Ground Advisory Working Group - Minute of Meeting of 20 May 2009 (Pages 25 - 30) 1.5 Committee Business Statement (Pages 31 - 32) 2. Membership of Sub-Committees 2.1 Evidential Hearings Sub Committee - 7 Members 2.2 Informal Business Panel - 7 Members 2.3 Taxi/Private Hire Car Consultation Group - 5 Members 2.4 Sports Ground Advisory Group - 5 Members 3. Applications for Grant, Renewal or Variation of Licences - List of Applications 3.1 Application for Grant of HMO Licence - 3/001 (Pages 33 - 36) 3.2 Application for Grant of HMO Licence - 3/002 (Pages 37 - 40) 3.3 Application for Grant of HMO Licence - 3/003 (Pages 41 - 44) 3.4 Application for Grant of HMO Licence - 3/004 (Pages 45 - 48) 3.5 Application for Grant of HMO Licence - 3/005 (Pages 49 - 52) 3.6 Application for Grant