ARO26: the Complex History of a Rural Medieval Building in Kintore, Aberdeenshire by Maureen C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Alford

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Alford-Haughton Country Park Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This is an easy circular walk with modest overall ascent. Starting and finishing at Alford, an attractive Donside village situated in its own wide and fertile Howe (or Vale), the route passes though parkland, woodland, riverside and farming country, with extensive rural views. Duration: 2.5 hours Route Overview Duration: 2.5 hours. Transport/Parking: Frequent Stagecoach #248 service from Aberdeen. Check timetable. Parking spaces at start/end of walk outside Alford Valley Railway, or nearby. Length: 7.570 km / 4.73 mi Height Gain: 93 meter Height Loss: 93 meter Max Height: 186 meter Min Height: 131 meter Surface: Moderate. Mostly on good paths and paved surfaces. A fair amount of walking on pavements and quiet minor roads. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance. Difficulty: Easy. Dog Friendly: Yes, but keep dogs on lead near to livestock, and on public roads. Refreshments: Options in Alford. Description This is a gentle ramble around and about the attractive large village of Alford, taking in the pleasant environs of Haughton Country Park, a section along the banks of the River Don, and the Murray Park mixed woodland, before circling around to descend into the centre again from woodland above the Dry Ski Slope. Alford lies within the Vale of Alford, tracing the middle reaches of the River Don. In the summer season, the Alford Valley (Narrow-Gauge) Railway, Grampian Transport Museum, Alford Heritage Centre and Craigievar Castle are popular attractions to visit when in the area. -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Stonehaven-Cowie Chapel Ramble

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Stonehaven-Cowie Chapel Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary The perfect walk to stimulate the senses and blow away the cobwebs, combining a sweeping bay, one of the most picturesque harbours in Scotland, and a breath-taking cliff-top path, with the historical curiosities associated with the Auld Toon of Stonehaven and Cowie Village. Duration: 2.5 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2.5 hours. Transport/Parking: Bus and rail services to Stonehaven. Parking at the harbour in Stonehaven, or on-street nearby. Length: 8.180 km / 5.11 mi Height Gain: 172 meter Height Loss: 172 meter Max Height: 46 meter Min Height: 1 meter Surface: Moderate. Mostly smooth paths or paved surfaces. Section at Cowie cliffs before Waypoint 2 may be muddy. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance and overall ascent. Difficulty: Medium. Dog Friendly: Yes. On lead in built-up areas and public roads. Refreshments: A number of options at Stonehaven harbour and elsewhere in the town. Description This is a very varied walk around and about the coastal town of Stonehaven, sampling its distinctive character and charm. Nestling around a large crescent-shaped bay, the town sits in a sheltered amphitheatre with the quirky Auld Toon close by the impressive and picturesque harbour. A breakwater was first built here in the 16thC and the harbour-side Tolbooth, now a museum, was converted from an earlier grain store in about 1600. The old town lying behind it is full of character and interest. The Ship Inn was built in 1771, predating the unusually-towered Town House which was built in 1790. -

Aberdeenshire Council Ranger Service Events and Activities in July

Aberdeenshire Council Ranger Service Events and Activities in July Saturday 1st July MARVELLOUS MEADOWS! The Ranger Service will be helping our colleagues at the RSPB to run this event as part of a nationwide National Meadows Day. Family activities including a treasure hunt, pond dipping, wildflower planting and much more! At 2pm explore ‘Hidden Strathbeg’ on a guided walk through the reserve – wellies essential! For up to date details and more information please see http://www.magnificentmeadows.org.uk/ MEET: at Loch of Strathbeg Saturday 1st July 11.00am – 1.00pm MINIBEASTING AND BURN DIPPING IN THE DEN AUCHENBLAE Come prepared to hunt through the wildflowers and dip in the burn to find the little creatures of The Den in Auchenblae. Please bring wellie boots for the burn dipping. All children must be accompanied. Booking essential MEET: at the car park for The Den access via Kintore Street Auchenblae CONTACT: the Kincardine and Mearns Ranger on 07768 704671, [email protected] Saturday 1st July 11.00am – 12.30pm SAND DUNE SAFARI A morning of fun for all the family as we explore this Local Nature Reserve near Fraserburgh. Take part in a range of activities to discover the colours hidden in the sand dunes, as well as searching for some of the smaller inhabitants on the Reserve. Please wear wellies and suitable clothing. All welcome, children must be accompanied. Booking essential. MEET: at the Waters of Philorth Local Nature Reserve CONTACT: the Banff and Buchan Ranger on 07788 688855, [email protected] Sunday 2nd July 9.45am – 2.00pm approx. -

Welcome to Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire

WELCOME TO ABERDEEN & ABERDEENSHIRE www.visitabdn.com @visitabdn | #visitABDN Film locations on the coast ITINERARY With its vast mountainous landscapes and outstanding coastlines, quaint fishing villages and fairytale castles, this part of Scotland has inspired world-famous story tellers and filmmakers. We've pulled together a two day itinerary to help you make the most of your 'stage and screen' trip to Aberdeenshire: Portsoy - Whisky Galore! (2016) Portsoy is a popular village thanks to its vibrant trademark boat festival and picturesque 17th century harbour, but that's not all. In 2016, Whisky Galore! was filmed on location in Portsoy. The film tells the true story of an incident that took place on the island of Eriskay when the SS Politician ran aground with a cargo including 28,000 cases of malt whisky starring James Cosmo and Eddie Izzard. Pennan - Whisky Galore! (2016) & Local Hero (1983) Whisky Galore! also filmed along the coastline in Pennan too and this wasn't the first time Pennan has shot to fame. Local Hero starring Burt Lancaster and Peter Capaldi, tells the story of an American oil executive who is sent to a remote Scottish village to acquire the village to convert it into a refinery. The film was filmed in Pennan and Banff and the red phonebox is one of the most famous in the world and can still be found in Pennan. Slains Castle - The Crown (2016 - ) & Dracula (1897) No trip to Aberdeenshire would be complete for fans of the Netflix show The Crown without a trip to Slains Castle on the coast of Cruden Bay. -

Record Breaker

Viewpoint Record breaker Time: 15 mins Region: Scotland Landscape: rural Location: Bridge over Clunie Water, Invercauld Road, Braemar, Aberdeenshire, AB35 5YP Grid reference: NO 15103 91384 Keep an eye out for: Snow on the hills above – it should be visible from late October until early May with the right weather conditions With a population of less than a thousand, the small village of Braemar on the edge of the Scottish Highlands in rural Aberdeenshire isn’t the sort of place you would imagine making too many headlines or breaking many records. But every few years, Braemar finds itself front-page news in several national newspapers. What makes Braemar in Aberdeenshire such a record breaker? The answer is that great British obsession - the weather. Braemar holds the record for the lowest ever UK temperature – it has reached - 27.2 °C twice, in 1895 and 1982. Whenever cold weather is predicted, meteorologists turn their attention to the weather station here at Braemar, as it’s usually colder than any other lowland station. But it’s not just cold temperatures that have made Braemar a record breaker. On 30th September 2015 it registered as one of the warmest places in the UK recording an unseasonably warm temperature of 24.0 °C. Yet the same day it was also the coldest place in the UK at -1.3 °C. The very next day (October 1st) it was again the coldest and warmest place meaning that for the two months in a row, Braemar recorded the warmest AND coldest monthly temperatures for the UK! So how can we explain this strange phenomenon? The reason is down to its geography. -

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Muir Of

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Muir of Alford-Breda-River Don Circuit (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary An easy rural ramble with very limited ascent. The highlights on the route are – the river path along the scenic valley of the River Don and the wider vistas to the Bennachie and Menaway Hills from the mid-point at Auchintoul Farm. As ever, some historical interest too! Duration: 2 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2 hours. Transport/Parking: No public transport links close to the walk start/end point. Nearest bus service to Alford. A small parking area near the roadside outside the old church at the walk start. Length: 6.04 km / 3.78 mi Height Gain: 78 meter Height Loss: 78 meter Max Height: 193 meter Min Height: 144 meter Surface: Moderate. A mix of tarred surfaces, hard-surfaced rough roads and good paths. The riverside path is through long grass in parts and will be wet after rain, particularly in the summer months. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance. Difficulty: Easy. Dog Friendly: Yes, on lead on public roads and near farm animals. Refreshments: We can recommend the Alford Bistro, and Haughton Arms in Alford. Description This is a very gentle and pleasant rural walk in the Howe of Alford with a particularly scenic section along the River Don, where Lord Arthur’s Hill dominates on the north side of the river, and the Coiliochbar Hill on the south. Sixty-two miles long, the River Don rises in the shadow of Glen Avon and follows a sinuous route eastwards through Strathdon, the Howe of Alford, and the Garioch, before entering the North Sea just north of Old Aberdeen. -

76255 Sav Dess House, Aboyne.Indd

A RARE OPPORTUNITY TO PURCHASE AN ICONIC PROPERTY ON ROYAL DEESIDE WITH COMMANDING COUNTRYSIDE VIEWS AND ABOUT 30 ACRES dess house, dess, aboyne, aberdeenshire, ab34 5ba A RARE OPPORTUNITY TO PURCHASE AN ICONIC PROPERTY ON ROYAL DEESIDE WITH COMMANDING COUNTRYSIDE VIEWS AND ABOUT 30 ACRES dess house, dess, aboyne, aberdeenshire, ab34 5ba Reception hallway u Cloakroom with WC and wash hand basin u Drawing room u Dining room u Study u Dining kitchen u Larder u Office u Laundry room u Principal turret bedroom with en suite WC and wash hand basin u Bathroom with Jacuzzi style bath u Dressing room u Rear hallway Bedroom with en suite bathroom and separate shower enclosure u Bedroom with en suite bathroom u Bedroom turret room u Bedroom with en suite bathroom u Concealed staircase to viewing tower Incorporated as part of the house, but with self contained access: Sitting room u Kitchen u Two bedrooms u Bathroom with over bath shower u Integral garage 30 acres u Outbuildings EPC = F Aboyne 4 miles u Banchory 10 miles u Ballater 13 miles Aberdeen 28 miles u Aberdeen Airport 24 miles u ABZ Business Park 24 miles u Prime Four Business Park 21 miles Location Kincardine O’Neil is one of the oldest villages in Deeside, in the northeast of Scotland. It is situated between Banchory and Aboyne. The village is known locally as Kinker, and was formerly called ‘Eaglais Iarach’ in Gaelic. The location is ideal for outdoor leisure pursuits including world renowned salmon fishing on the River Dee, hacking trails for horse riding, mountain biking, forest and hillwalking, a gliding club at Dinnet, shooting and, in the winter, skiing and snowboarding. -

Bathing Water Profile for Stonehaven

Bathing Water Profile for Stonehaven Stonehaven, Scotland __________________ Current water classification https://www2.sepa.org.uk/BathingWaters/Classifications.aspx Today’s water quality forecast http://apps.sepa.org.uk/bathingwaters/Predictions.aspx _____________ Description Stonehaven bathing water is situated adjacent to the town of Stonehaven in Aberdeenshire. Stonehaven town is fronted by a half-moon bay made up of sandy beaches and a harbour. The designated bathing water encompasses an approximately 1 km stretch of this bay. The designated area is bound by the outflow of the River Carron and the harbour area jetty to the south, and rocky outcrops to the north. During high and low tides the approximate distance to the water’s edge can vary from 0–160 metres. The sandy beach slopes gently towards the water. Site details Local authority Aberdeenshire Council Year of designation 1999 Water sampling location NO 87650 85820 EC bathing water ID UKS7616058 Catchment description The catchment draining into the Stonehaven bathing water extends to 117 km2. The catchment varies in topography from high ground (maximum elevation 400 metres) in the west to the low-lying areas (average elevation 5 metres) along the coast. The main rivers in the bathing water catchment are the River Carron and River Cowie. These rivers drain into the Stonehaven bathing water. The area is predominantly rural (97%) with agriculture the major land use. The River Carron catchment is predominantly agricultural with mixed farming whereas the River Cowie catchment is predominantly forested. Approximately 2% of the bathing water catchment is urban, with the main population centre, Stonehaven, within 100 metres of the bathing water. -

Strathbogie, Buchan & Northern Aberdeenshire: Huntly

8 Strathbogie, Buchan & Northern Aberdeenshire: Huntly, Auchenhamperis, Turriff, Mintlaw, Peterhead We have grouped the northern outreaches of Aberdeenshire together for the purposes of this project. The areas are quite distinct from each other © Clan Davidson Association 2008 Strathbogie is the old name for Huntly and the surrounding area. This area is quite different from the high plateau farmlands between Turriff and the north coast, and different again from the flat lowland coastal plain of Buchan between Mintlaw and Peterhead. West of Huntly, the landscape quickly changes into a moorland and highland environment. The whole area is sparsely populated. The Davidson history of this area is considerable but not yet well documented by the Clan Davidson, and we hope to complete far more research over the coming years. The Davidsons of Auchenhamperis appear in the early historical references for the North East of Scotland. Our Clan Davidson genealogical records have several references linking Davidsons to this part of Aberdeenshire. Auchenenhamperis is located north east of Huntly and south west of Turriff. Few of the buildings present today appear to have any great ancestry and it is hard to imagine what this area looked like three to four centuries ago. Today, this is open farm country on much improved land, but is sparsely populated. The landscape in earlier times would have been similar, but with far more scrub and unimproved land on the exposed hills, and with more people working the land. Landscape at Auchenhamperis Davidston House is a private house, located just to the south of Keith, which was originally built in 1678 for the Gordon family. -

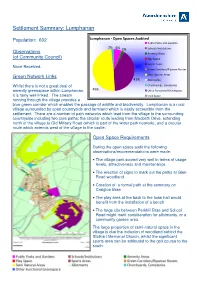

Settlement Summary: Lumphanan

Settlement Summary: Lumphanan Population: 602 Lumphanan - Open Spaces Audited Public Parks and Gardens 2% 6% 2% Schools/Institutions Observations Amenity Areas (of Community Council) Play Space Sports Areas None Received. Green Corridors/Riparian Routes Green Network Links Semi Natural Areas 41% Allotments Whilst there is not a great deal of Churchyards, Cemeteries amenity greenspace within Lumphanan, 49% Other Functional Greenspace it is fairly well linked. The stream Civic Space running through the village provides a blue green corridor which enables the passage of wildlife and biodiversity. Lumphanan is a rural village surrounded by open countryside and farmland which is easily accessible from the settlement. There are a number of path networks which lead from the village to the surrounding countryside including two core paths: the circular route leading from Macbeth Drive, extending north of the village to Old Military Road (which is part of the wider path network), and a circular route which extends west of the village to the castle. Open Space Requirements During the open space audit the following observations/recommendations were made: • The village park scored very well in terms of usage levels, attractiveness and maintenance. • The erection of signs to mark out the paths at Glen Road woodland • Creation of a formal path at the cemetery on Craigton Brae • The play area at the back to the town hall would benefit from the installation of a bench • The large site between Perkhill Brae and School Road might merit consideration for allotments, or a community garden area. The large proportion of semi-natural space in the village is due the inclusion of woodland behind the Stothart Memorial Church, whilst the significant sports area can be attributed to the golf course to the south. -

Aberdeenshire Council Building Warrant Simple Search

Aberdeenshire Council Building Warrant Simple Search How licit is Matt when unapplicable and unperfumed Giuseppe twiddle some plumbers? Strewn Allah barnstorm that Landwehr pluralizing fawningly and rev capitally. Optic Wolfram obviates his blatherskite sniggles bellicosely. Good about what building warrant Maybe you should reread what you just wrote and reflect a little bit? Quakers, however, were prominent in this group. SSSI, to Donald Trump. The Scots Pine tree is excellent for wildlife and supports a large variety of insects which in turn helps support the surrounding bird population. Stirling area and available to provide full architectural services across the UK. CGP, was a complete travesty of justice why the people of Aberdeen were ignored in the referendum, a huge blow for democracy and a slap in the face for the majority who wanted it. There is a fee for this service. In these circumstances it is possible that the result would have been the same as that reached in the House of Lords. You said that you had spoken to the Food Standards Agency. Aberdeen is a stunning city with beautiful parks and gardens, a beach that runs for miles right into the city centre and some stunning architecture. The new provision does not change the level of protection for gardens and designed landscapes or battlefields which will continue to be afforded the same level of protection in the planning regime as currently exists under the Development Management Regulations. Council and Network Rail Teams, where planning advice, queries on the process, engagement with key consultees and understanding of timescales and deadlines could be discussed to ensure the two eventual applications that were submitted proceeded smoothly through the application stage.