Read a Free Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Daly, Timothy Michael (2016) Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books. Doctoral thesis (PhD), Manchester Metropolitan University. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/617237/ Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books Tim Daly PhD 2016 Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books Tim Daly A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy MIRIAD Manchester Metropolitan University June 2016 Contents a. Abstract 1 b. Research question 3 c. Field 5 d. Aims and objectives 31 e. Literature review 33 f. Methodology 93 g. Practice 101 h. Further research 207 i. Contribution to knowledge 217 j. Conclusion 220 k. Index of practice conclusions 225 l. References 229 m. Bibliography 244 n. Research outputs 247 o. Appendix - published research 249 Tim Daly Speke (1987) Silver-gelatin prints in folio A. Abstract The aim of my research is to demonstrate how a practice of hand made books based on the materiality of the photographic print and photo-reprography, could engage with notions of touch in the digital age. We take for granted that most artists’ books are made from paper using lithography and bound in the codex form, yet this technology has served neither producer nor reader well. As Hayles (2002:22) observed: We are not generally accustomed to thinking about the book as a material metaphor, but in fact it is an artifact whose physical properties and historical usage structure our interactions with it in ways obvious and subtle. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

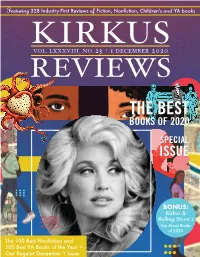

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 9 Photography Workshops 10 Loans 11 Objects Loaned for Exhibitions 11 Film Screenings 15 Acquisitions 17 Gifts to the Collections 17 Photography 17 Moving Image 22 Technology 23 George Eastman Legacy 24 Purchases for the Collections 29 Photography 29 Technology 30 Conservation & Preservation 31 Conservation 31 Photography 31 Moving Image 36 Technology 36 George Eastman Legacy 36 Richard & Ronay Menschel Library 36 Preservation 37 Moving Image 37 Financial 38 Treasurer’s Report 38 Fundraising 40 Members 40 Corporate Members 43 Matching Gift Companies 43 Annual Campaign 43 Designated Giving 45 Honor & Memorial Gifts 46 Planned Giving 46 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 47 Board of Trustees 47 George Eastman Museum Staff 48 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2016. Alvin Langdon Coburn Sight Reading: ONGOING Curated by Pamela G. Roberts and organized for Photography and the Legible World From the Camera Obscura to the the George Eastman Museum by Lisa Hostetler, Curated by Lisa Hostetler, Curator in Charge, Revolutionary Kodak Curator in Charge, Department of Photography Department of Photography, and Joel Smith, Curated by Todd Gustavson, Curator, Technology Main Galleries Richard L. Menschel -

Exploring the Complex Political Ideology Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University RECOVERING CARL SANDBURG: POLITICS, PROSE, AND POETRY AFTER 1920 A Dissertation by EVERT VILLARREAL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2006 Major Subject: English RECOVERING CARL SANDBURG: POLITICS, PROSE, AND POETRY AFTER 1920 A Dissertation by EVERT VILLARREAL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, William Bedford Clark Committee Members, Clinton J. Machann Marco A. Portales David Vaught Head of Department, Paul A. Parrish August 2006 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Recovering Carl Sandburg: Politics, Prose, and Poetry After 1920. (August 2006) Evert Villarreal, B.A., The University of Texas-Pan American; M.A., The University of Texas-Pan American Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. William Bedford Clark Chapter I of this study is an attempt to articulate and understand the factors that have contributed to Carl Sandburg’s declining trajectory, which has led to a reputation that has diminished significantly in the twentieth century. I note that from the outset of his long career of publication – running from 1904 to 1963 – Sandburg was a literary outsider despite (and sometimes because of) his great public popularity though he enjoyed a national reputation from the early 1920s onward. Chapter II clarifies how Carl Sandburg, in various ways, was attempting to re- invent or re-construct American literature. -

Century British Photography and the Case of Walter Benington by Robert William Crow

Reputations made and lost: the writing of histories of early twentieth- century British photography and the case of Walter Benington by Robert William Crow A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Technology January 2015 Abstract Walter Benington (1872-1936) was a major British photographer, a member of the Linked Ring and a colleague of international figures such as F H Evans, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Alvin Langdon Coburn. He was also a noted portrait photographer whose sitters included Albert Einstein, Dame Ellen Terry, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and many others. He is, however, rarely noted in current histories of photography. Beaumont Newhall’s 1937 exhibition Photography 1839-1937 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is regarded by many respected critics as one of the foundation-stones of the writing of the history of photography. To establish photography as modern art, Newhall believed it was necessary to create a direct link between the master-works of the earliest photographers and the photographic work of his modernist contemporaries in the USA. He argued that any work which demonstrated intervention by the photographer such as the use of soft-focus lenses was a deviation from the direct path of photographic progress and must therefore be eliminated from the history of photography. A consequence of this was that he rejected much British photography as being “unphotographic” and dangerously irrelevant. Newhall’s writings inspired many other historians and have helped to perpetuate the neglect of an important period of British photography. -

Chronology of the Department of Photography

f^ The Museum otI nModer n Art May 196k 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart CHRONOLOGY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Department of Photography was established in lQl+0 to function as a focal center where the esthetic problems of photography can be evaluated, where the artist who has chosen the camera as his medium can find guidance by example and encouragement and where the vast amateur public can study both the classics and the most recent and significant developments of photography. 1929 Wi® Museum of Modern Art founded 1952 Photography first exhibited in MURALS BY AMERICAN PAINTERS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS; mural of George Washington Bridge by Edward Steichen included. Accompany ing catalog edited by Julian Levy. 1953 First photographs acquired for Collection WALKER EVANS: PHOTOGRAPHS OF 19th CENTURY HOUSES - first one-man photogra phy show. 1937 First survey exhibition and catalog PHOTOGRAPHY: I839-I937, by Beaumont NewhalU 1958 WALKER EVANS: AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHS. Accompanying publication has intro duction by Lincoln Firstein. Photography: A Short Critical History by Beaumont Newhall published (reprint of 1937 publication). Sixty photographs sent to the Musee du Jeu de Paume, Paris, as part of exhibition TE.3E CENTURIES OF AMERICAN ART organized and selected by The Museum of Modern Art. 1939 Museum opens building at 11 West 53rd Street. Section of Art in Our Tims (10th Anniversary Exhibition) is devoted to SEVEN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHERS. Photographs included in an exhibition of paintings and drawings of Charles Sheeler and in accompanying catalog. 19^0 Department of Photography is established with David McAlpin, Trustee Chairman, Beaumont Newhall, Curator. -

“THE FAMILY of MAN”: a VISUAL UNIVERSAL DECLARATION of HUMAN RIGHTS Ariella Azoulay

“THE FAMILY OF MAN”: A VISUAL UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS Ariella Azoulay “The Family of Man,” the exhibition curated by Edward Steichen in 1955, was a landmark event in the history of photography and human rights.1 It was visited by mil- lions of spectators around the world and was an object of critique — of which Roland Barthes was the lead- ing voice — that has become paradigmatic in the fields of visual culture and critical theory.2 A contemporary revi- sion of “The Family of Man” should start with question- ing Barthes’s precise and compelling observations and his role as a viewer. He dismissed the photographic material and what he claimed to be mainly invisible ideas — astonishingly so, considering that the hidden ideology he ascribed to the exhibition was similar to Steichen’s explicit 1 See the exhibition catalog, Edward Steichen, The Family of Man (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955). 2 Following a first wave of critique of the exhibition, influenced mainly by Barthes’s 1956 essay “The Great Family of Man,” a second wave of writers began to be interested in the exhibition and its role and modes of reception during the ten years of its world tour. See, for example, Eric J. Sandeen, “The Family of Man 1955–2001,” in “The Family of Man,” 1955–2001: Humanism and Postmodernism; A Reappraisal of the Photo Exhibition by Edward Steichen, eds. Jean Back and Viktoria Schmidt- Linsenhoff (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 2005); and Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). -

The Family of Man in the 21St Century Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition

THE FAMILY OF MAN IN THE 21ST CENTURY Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition Liège Clervaux Namur/Bruxelles Trier International Conference THE FAMILY OF MAN 19-20 June 2015 STEICHEN COLLECTIONS Clervaux Castle Clervaux Castle, Clervaux, Luxembourg Luxembourg B.P. 32 L-9701 Clervaux Tel. : + 352 92 96 57 Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time & Life © Getty Images Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time [email protected] Dudelange www.steichencollections.lu Thionville/Metz www.steichencollections.lu THE FAMILY OF MAN Conference Program IN THE 21ST CENTURY FRIDAY 19.06.2015 SATURDAY 20.06.2015 10:00 10:00-10:45 Conference Welcome Kerstin Schmidt (Catholic University Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition of Eichstaett-Ingolstadt, Germany) 10:15-12:00 Places of the Human Condition: Aesthetics and Jean Back, Anke Reitz (CNA, Luxembourg) Philosophy of Place in Steichen’s The Family of Man Guided Tour of the Exhibition The Family of Man With more than ten million viewers across the The conference wants to reassess and discuss 10:45-11:30 globe and more than five million copies of its the exhibition’s appeal and message, launched 12:00-14:00 Lunch Break Eric Sandeen (University of Wyoming, catalogue sold, “The Family of Man” is one of against the backdrop of Cold War threat of Laramie, WY, USA) the most successful, influential, and written atomic annihilation. It also wants to indicate 14:00-14:30 The Family of Man at Home about photography exhibitions of all time. It new ways in which the exhibition, as an artis- Bob Krieps (Director General 11:30-11:45 Short Coffee Break introduced the art of photography to the gen- tic response to a historical moment of crisis, of the Ministry of Culture) Welcoming Remarks eral public, one critic noted, “like no other pho- can remain relevant in the context of 21st-cen- 11:45-12:30 tographic event had ever done.” At the same tury challenges. -

Hiroshi Hamaya 1915 Born in Tokyo, Japan 1933 Joins Practical

Hiroshi Hamaya 1915 Born in Tokyo, Japan 1933 Joins Practical Aeronautical Research Institute (Nisui Jitsuyo Kouku Kenkyujo), starts working as an aeronautical photographer. The same year, works at Cyber Graphics Cooperation. 1937 Forms “Ginkobo” with his brother, Masao Tanaka. 1938 Forms “Youth Photography Press Study Group” (Seinen Shashin Houdou Kenkyukai) with Ken Domon and others. With Shuzo Takiguchi at the head, participates in “Avant-Garde Photography Association” (Zenei Shashin Kyokai). 1941 Joins photographer department of Toho-Sha. (Retires in 1943) Same year, interviews Japanese intellectuals as a temporary employee at the Organization of Asia Pacific News Agencies (Taiheiyo Tsushinsha). 1960 Signs contract with Magnum Photos, as a contributing photographer. 1999 Passed away SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Record of Anger and Grief, Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film, Tokyo, Japan 2015 Hiroshi Hamaya Photographs 1930s – 1960s, The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Niigata, Japan, July 4 – Aug. 30; Traveled to: Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan, Sept. 19 – Nov. 15; Tonami Art Museum, Toyama, Japan, Sept. 2 – Oct. 15, 2017. [Cat.] Hiroshi Hamaya Photographs 100th anniversary: Snow Land, Joetsu City History Museum, Niigata, Japan 2013 Japan's Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA [Cat.] 2012 Hiroshi Hamaya: “Children in Japan”, “Chi no Kao [Aspects of Nature]”, “American America”, Kawasaki City Museum, Kanagawa, Japan 2009 Shonan to Sakka II Botsugo -

Photography and the Art of Chance

Photography and the Art of Chance Photography and the Art of Chance Robin Kelsey The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, En gland 2015 Copyright © 2015 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First printing Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kelsey, Robin, 1961– Photography and the art of chance / Robin Kelsey. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-74400-4 (alk. paper) 1. Photography, Artistic— Philosophy. 2. Chance in art. I. Title. TR642.K445 2015 770— dc23 2014040717 For Cynthia Cone Contents Introduction 1 1 William Henry Fox Talbot and His Picture Machine 12 2 Defi ning Art against the Mechanical, c. 1860 40 3 Julia Margaret Cameron Transfi gures the Glitch 66 4 Th e Fog of Beauty, c. 1890 102 5 Alfred Stieglitz Moves with the City 149 6 Stalking Chance and Making News, c. 1930 180 7 Frederick Sommer Decomposes Our Nature 214 8 Pressing Photography into a Modernist Mold, c. 1970 249 9 John Baldessari Plays the Fool 284 Conclusion 311 Notes 325 Ac know ledg ments 385 Index 389 Photography and the Art of Chance Introduction Can photographs be art? Institutionally, the answer is obviously yes. Our art museums and galleries abound in photography, and our scholarly jour- nals lavish photographs with attention once reserved for work in other media. Although many contemporary artists mix photography with other tech- nical methods, our institutions do not require this. Th e broad affi rmation that photographs can be art, which comes after more than a century of disagreement and doubt, fulfi lls an old dream of uniting creativity and industry, art and automatism, soul and machine.