Indigenous Mobilization and the Chilean State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200911 Lista De EDS Adheridas SCE Convenio GM-Shell

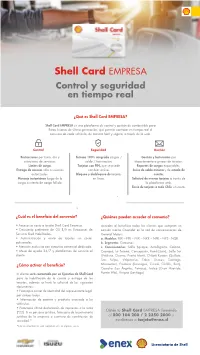

Control y seguridad en tiempo real ¿Qué es Shell Card EMPRESA? Shell Card EMPRESA es una plataforma de control y gestión de combustible para flotas livianas de última generación, que permite controlar en tiempo real el consumo de cada vehículo, de manera fácil y segura, a través de la web. Restricciones por hora, día y Sistema 100% integrado cargas / Gestión y facturación por estaciones de servicios. saldo / facturación. departamento o grupos de tarjetas. Límites de carga. Tarjetas con PIN, que se puede Reportes de cargas exportables. Entrega de accesos sólo a usuarios cambiar online. Aviso de saldo mínimo y de estado de autorizados. Bloqueo y desbloqueo de tarjetas cuenta. Mensaje instantáneo luego de la en línea. Solicitud de nuevas tarjetas a través de carga o intento de carga fallida. la plataforma web. Envío de tarjetas a todo Chile sin costo. ¿Cuál es el beneficio del convenio? ¿Quiénes pueden acceder al convenio? • Acceso sin costo a tarjeta Shell Card Empresa. Acceden al beneficio todos los clientes que compran un • Descuento preferente de -20 $/lt en Estaciones de camión marca Chevrolet en la red de concesionarios de Servicio Shell Habilitadas. General Motors. • Administración y envío de tarjetas sin costos a. Modelos: FRR – FTR – FVR – NKR – NPR – NPS - NQR. adicionales. b. Segmento: Camiones. • Atención exclusiva con ejecutivo comercial dedicado. c. Concesionarios: Salfa (Iquique, Antofagasta, Calama, • Mesa de ayuda 24/7 y plataformas de servicio al Copiapó, La Serena, Concepción, Rondizzoni), Salfa Sur cliente. (Valdivia, Osorno, Puerto Montt, Chiloé) Kovacs (Quillota, San Felipe, Valparaíso, Talca, Linares, Santiago, ¿Cómo activar el beneficio? Movicenter), Frontera (Rancagua, Curicó, Chillán, Buin), Coseche (Los Ángeles, Temuco), Inalco (Gran Avenida, El cliente será contactado por un Ejecutivo de Shell Card Puente Alto), Vivipra (Santiago). -

La Resistencia Mapuche-Williche, 1930-1985

La resistencia mapuche-williche, 1930-1985. Zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin im März 2019. Vorgelegt von Alejandro Javier Cárcamo Mansilla aus Osorno, Chile 1 1. Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Stefan Rinke, Freie Universität Berlin ZI Lateinamerika Institut 2. Gutachter: apl. Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Böttcher, Freie Universität Berlin ZI Lateinamerika Institut Tag der Disputation: 09.07.2019 2 Índice Agradecimientos ....................................................................................................................... 5 Introducción .............................................................................................................................. 6 La resistencia mapuche-williche ............................................................................................ 8 La nueva historia desde lo mapuche ..................................................................................... 17 Una metodología de lectura a contrapelo ............................................................................. 22 I Capítulo: Características de la subalternidad y la resistencia mapuche-williche en el siglo XX. .................................................................................................................................. 27 Resumen ............................................................................................................................... 27 La violencia cultural como marco de la resistencia -

The Permanent Rebellion: an Interpretation of Mapuche Uprisings Under Chilean Colonialism Fernando Pairican 1,* and Marie Juliette Urrutia 2

Radical Americas Special issue: Chile’s Popular Unity at 50 Article The permanent rebellion: An interpretation of Mapuche uprisings under Chilean colonialism Fernando Pairican 1,* and Marie Juliette Urrutia 2 1 Doctor of History, University of Santiago, Santiago, Chile 2 Social Anthropology MA Student, CIESAS Sureste, Las Peras, San Martin, Chiapas, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] How to Cite: Pairican, F., Urrutia, M. J. ‘The permanent rebellion: An interpretation of Mapuche uprisings under Chilean colonialism’. Radical Americas 6, 1 (2021): 12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.ra.2021.v6.1.012. Submission date: 30 January 2021; Acceptance date: 25 March 2021; Publication date: 1 June 2021 Peer review: This article has been peer-reviewed through the journal’s standard double-blind peer review, where both the reviewers and authors are anonymised during review. Copyright: c 2021, Fernando Pairican and Marie Juliette Urrutia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY) 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited • DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.ra.2021.v6.1.012. Open access: Radical Americas is a peer-reviewed open-access journal. Abstract This article approaches the rebellions of the Mapuche people from a longue-durée perspective, from the Occupation of the Araucanía in 1861 to the recent events of 2020. Among other things, the article explores the Popular Unity (UP) period, and the ‘Cautinazo’ in particular, considered here as an uprising that synthesised the discourses and aspirations of the Mapuche people dating back to the Occupation, while also repoliticising them by foregrounding demands for land restitution. -

Permanent War on Peru's Periphery: Frontier Identity

id2653500 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ’S PERIPHERY: FRONT PERMANENT WAR ON PERU IER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH CENTURY CHILE. By Eugene Clark Berger Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Date: Jane Landers August, 2006 Marshall Eakin August, 2006 Daniel Usner August, 2006 íos Eddie Wright-R August, 2006 áuregui Carlos J August, 2006 id2725625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY ’ PERMANENT WAR ON PERU S PERIPHERY: FRONTIER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH-CENTURY CHILE EUGENE CLARK BERGER Dissertation under the direction of Professor Jane Landers This dissertation argues that rather than making a concerted effort to stabilize the Spanish-indigenous frontier in the south of the colony, colonists and indigenous residents of 17th century Chile purposefully perpetuated the conflict to benefit personally from the spoils of war and use to their advantage the resources sent by viceregal authorities to fight it. Using original documents I gathered in research trips to Chile and Spain, I am able to reconstruct the debates that went on both sides of the Atlantic over funds, protection from ’ th pirates, and indigenous slavery that so defined Chile s formative 17 century. While my conclusions are unique, frontier residents from Paraguay to northern New Spain were also dealing with volatile indigenous alliances, threats from European enemies, and questions about how their tiny settlements could get and keep the attention of the crown. -

Lautaro Aprendid Tdcticas Guerreras Cziado, Hecho Prisiouero, Fue Cnballerixo De Don Pedro De Valdivia

ISIDORA AGUIRRE (Epopeya del pueblo mapuche) EDITORIAL NASCIMENTO SANTIAGO 1982 CHILE A mi liermano Fernundo Aprendemos en 10s textos de historin que 10s a+.aucauos’ -ellos prelieren llamnrse “mapuches”, gente de la tierra- emu by’icosos y valzentes, que rnantuvieron en laque a 10s espagoks en una guerrn que durd tres siglos, qzie de nigh modo no fueron vencidos. Pero lo que machos tgnoran es qzic adrt siguen luckando. Por !a tierra en comunidad, por un modo de vida, por comervur su leizgua, sus cantos, sa cultura y sus tradiciones como algo VIVO y cotediano. Ellos lo resumen el?’ pocas palabras: ‘(Iuchamos por conservar nuez- tra identidad, por integrarnos a in sociedad chilena mnyorita- ria sin ser absorbidos por e1Ja”. Sabemos cdmo murid el to- pi Caupolica‘n, cdmo Lautaro aprendid tdcticas guerreras cziado, hecho prisiouero, fue cnballerixo de don Pedro de Valdivia. Sabemos, en suma, que no fueron vencidos, pero iporamos el “cdlno” y el “por que”‘. Nay nurneroros estudios antropoldgicos sobre 10s map- rhes pero se ha hecho de ellos muy poca difusidn. Y menos conocemos aun su vida de hoy, la de esu minoria de un me- dio rnilldiz de gentes que viven en sus “reducidus” redwcio- nes del Sur. Sabemos que hay machis, que kacen “nguillatu- 7 nes”, que hay festivales folcldricos, y en los mercados y en los museos podemos ver su artesania. Despuh de la mal llamada “Pacificacidn de la Arauca- nia” de fines del siglo pasado -por aquello de que la fami- lia crece y la tierra no-, son muchos los hz’jos que emigran a las ciudades; 10s nifios se ven hoscos y algo confundidos en las escuelas rurales, porque los otros se burlan de su mal castellano; sin embargo son nifios de mente cigil que a los seis afios hablan dos lenguas, que llevan una doble vida, por miedo a la discriminacidn, la de la ruca. -

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago De Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago de Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space vorgelegt von Walter Alejandro Imilan Ojeda Von der Fakultät VI - Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften Dr.-Ing. genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. -Ing. Johannes Cramer Berichter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Peter Herrle Berichter: Prof. Dr. phil. Jürgen Golte Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 18.12.2008 Berlin 2009 D 83 Acknowledgements This work is the result of a long process that I could not have gone through without the support of many people and institutions. Friends and colleagues in Santiago, Europe and Berlin encouraged me in the beginning and throughout the entire process. A complete account would be endless, but I must specifically thank the Programme Alßan, which provided me with financial means through a scholarship (Alßan Scholarship Nº E04D045096CL). I owe special gratitude to Prof. Dr. Peter Herrle at the Habitat-Unit of Technische Universität Berlin, who believed in my research project and supported me in the last five years. I am really thankful also to my second adviser, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Golte at the Lateinamerika-Institut (LAI) of the Freie Universität Berlin, who enthusiastically accepted to support me and to evaluate my work. I also owe thanks to the protagonists of this work, the people who shared their stories with me. I want especially to thank to Ana Millaleo, Paul Paillafil, Manuel Lincovil, Jano Weichafe, Jeannette Cuiquiño, Angelina Huainopan, María Nahuelhuel, Omar Carrera, Marcela Lincovil, Andrés Millaleo, Soledad Tinao, Eugenio Paillalef, Eusebio Huechuñir, Julio Llancavil, Juan Huenuvil, Rosario Huenuvil, Ambrosio Ranimán, Mauricio Ñanco, the members of Wechekeche ñi Trawün, Lelfünche and CONAPAN. -

VITTORIO QUEIROLO Vittorio Queirolo

1 VITTORIO QUEIROLO Vittorio Queirolo Vittorio Esteban Queirolo Ayala nació el 26 de diciembre de 1963 en Talcahuano, Chile. Biografía Vittorio Esteban Queirolo Ayala nació el 26 de diciembre de 1963 en Talcahuano, Chile. Entre 1986 y 1991 estudió Licenciatura en Arte, Mención Dibujo, en la Universidad Católica de Chile. Al terminar sus estudios regresó a Talcahuano, donde creó su taller de arte en los años noventa y destacó en distintos salones nacionales. A mediados de la década se trasladó a Santiago, ciudad en la que entre 1995 y 2003 realizó clases de pintura. Su trabajo como pintor, que ha sido expuesto en Chile y en el extranjero, aborda diversos temas y estilos como naturalezas muertas, paisajes de corte expresionista y, más recientemente, ha explorado las posibilidades de la abstracción. Además, es socio fundador del Foto Cine Club de la Universidad de Temuco, inaugurado en 1987. El artista reside en Santiago, Chile. Premios, distinciones y concursos 2013 Premio in situ Ricardo Anwanter categoría figurativo y mención honrosa categoría envío, XXX Salón Internacional Valdivia y su Río, Valdivia, Chile. 2011 Segundo lugar, Concurso Nacional Pinceladas Contra Viento y Marea, Municipalidad de Talcahuano, Talcahuano, Chile. 2000 Tercer lugar especialidad Pintura, X versión del Concurso nacional de pintura El color del sur, Santiago, Chile. 1999 Tercer lugar, Segundo Salón Nacional de Pintura Invierno-Primavera, Instituto Chileno Japonés de Cultura, Santiago, Chile. 2 1999 Premio Municipal de Arte, Municipalidad de Talcahuano, Talcahuano, Chile. 1994 Mención Especial In Situ, El color del sur, Puerto Varas, Chile. 1993 Primer Premio en Pintura, Empresas Empremar, Valparaíso, Chile. -

Processes of Signification and Resignification of a City, Temuco 1881-2019

CIUDAD RESIGNIFICADA PROCESSES OF SIGNIFICATION AND RESIGNIFICATION OF A CITY, TEMUCO 1881-2019 Procesos de significación y resignificación de una ciudad, Temuco 1881-20198 Processos de significado e ressignificação de uma cidade, Temuco 1881-2019 Jaime Edgardo Flores Chávez Académico, Departamento de Ciencias Sociales e Investigador del Centro de Investigaciones Territoriales (CIT). Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile. [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6153-2922 Dagoberto Godoy Square or the Hospital, in the background the statue of Caupolicán and the Conun Huenu hill. Source: Jaime Flores Chávez. This article was funded by the Research Directorate of the University of La Frontera, within the framework of projects DIUFRO No. DI19-0028, No. DI15-0045 and No. DI15-0026. Articulo recibido el 04/05/2020 y aceptado el 24/08/2020. https://doi.org/10.22320/07196466.2020.38.058.02 CIUDAD RESIGNIFICADA ABSTRACT The social unrest that unfolded from October 2019 on saw, among its most visible expressions, the occupation of public spaces like streets, avenues and squares. The “attack” on the monuments that some associated with a kind of rebellion against the history of Chile was also extensively recorded. These events lead us along the paths of history, memory, remembrance and oblivion, represented in monuments, official symbols, the names of streets, squares and parks around the city, and also, along interdisciplinary paths to ad- dress this complexity using diverse methodologies and sources. This article seeks to explain what happened in Temuco, the capital of the Araucanía Region, during the last few months of 2019. For this purpose, a research approach is proposed using a long-term perspective that makes it possible to find the elements that started giving a meaning to the urban space, to then explore what occurred in a short time, between October and November, in the logic of the urban space resignification process. -

Indigenous Peoples Rights And

ISBN 978-0-692-88605-2 Intercultural Conflict and Peace Building: The Experience of Chile José Aylwin With nine distinct Indigenous Peoples and a population of 1.8 million, which represents 11% of the total population of the country,1 conflicts between Indigenous Peoples and the Chilean state have increased substantially in recent years. Such conflicts have been triggered by different factors including the lack of constitutional recognition of Indigenous Peoples; political exclusion; and the imposition of an economic model which has resulted in the proliferation of large developments on Indigenous lands and territories without proper consultation, even less with free, prior, and informed consent, and with no participation of the communities directly affected by the benefits these developments generate. The growing awareness among Indigenous Peoples of the rights that have been internationally recognized to them, and the lack of government response to their claims—in particular land claims—also help to explain this growing conflict. Chile is one of the few, if not the only state in the region, which does not recognize Indigenous Peoples, nor does it recognize their collective rights, such as the right to political participation or autonomy or the right to lands and resources, in its political Constitution. The current Chilean Constitution dates back to 1980, when it was imposed by the Pinochet dictatorship. Indigenous Peoples have also been severely impacted by the market economy prevalent in the country. In recent decades, Chile has signed free trade and investment agreements with more than 60 other countries, in particular large economies from the Global North including the United States, Canada, the European Union, China and Japan, among others. -

210315 Eds Adheridas Promo Ilusión Copia

SI ERES TRANSPORTISTA GANA UN K M Disponible Estaciones de servicios Shell Card TRANSPORTE Dirección Ciudad Comuna Región Pudeto Bajo 1715 Ancud Ancud X Camino a Renaico N° 062 Angol Angol IX Antonio Rendic 4561 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Caleta Michilla Loteo Quinahue Antofagasta Antofagasta II Pedro Aguirre Cerda 8450 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Panamericana Norte Km. 1354, Sector La Negra Antofagasta Antofagasta II Av. Argentina 1105/Díaz Gana Antofagasta Antofagasta II Balmaceda 2408 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Pedro Aguirre Cerda 10615 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Camino a Carampangue Ruta P 20, Número 159 Arauco Arauco VIII Camino Vecinal S/N, Costado Ruta 160 Km 164 Arauco Arauco VIII Panamericana Norte 3545 Arica Arica XV Av. Gonzalo Cerda 1330/Azola Arica Arica XV Av. Manuel Castillo 2920 Arica Arica XV Ruta 5 Sur Km.470 Monte Águila Cabrero Cabrero VII Balmaceda 4539 Calama Calama II Av. O'Higgins 234 Calama Calama II Av. Los Héroes 707, Calbuco Calbuco Calbuco X Calera de Tango, Paradero 13 Calera de Tango Santiago RM Panamericana Norte Km. 265 1/2 Sector de Huentelauquén Canela Coquimbo IV Av. Presidente Frei S/N° Cañete Cañete VIII Las Majadas S/N Cartagena Cartagena V Panamericana Norte S/N, Ten-Ten Castro Castro X Doctor Meza 1520/Almirante Linch Cauquenes Cauquenes VII Av. Americo Vespucio 2503/General Velásquez Cerrillos Santiago XIII José Joaquín Perez 7327/Huelen Cerro Navia Santiago XIII Panamericana Norte Km. 980 Chañaral Chañaral III Manuel Rodríguez 2175 Chiguayante Concepción VIII Camino a Yungay, Km.4 - Chillán Viejo Chillán Chillán XVI Av. Vicente Mendez 1182 Chillán Chillán XVI Ruta 5 Sur Km. -

The New Zealand Gazette 581

MAY 9] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 581 CHILE CHILE-continued Name. Address. Name. Address. A.E.G., Cia Sudamerikana de Bandera 581, Casilla 9393', De la Ruelle, Jean Marie Santiago. Elecricidad Santiago. Deutsch-Chilenischer Bund Agustinas 975, Santiago. Aachen y Munich, Cia de Seguros Blanco 869, Valparaiso. Deutsche Handelskammer Prat 846, Casilla. 1411,VaIapraiso, Ackerknecht, E. " Esmeralda, 1013, Casilla 1784, and Morande 322, Casilla 4252, Valparaiso. Santiago. Ackermann Lochmann, Luis San Felipe 181, Casilla 227, Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. Bandera 191, Santiago, and .all Puerto Montt. branches in Chile. Agricola Caupolican Ltda. Soc ... Santiago. Deutsche Zeitung fur Chile Merced 673, Santiago. Agricola e Industrial "San Agustinas 975, Santiago, and all Deutscher Sports Verein Margarita 2341, Santiago. Pedro" Ltda., Soc. branches in Chile. Deutscher Verein Salvador Dorroso 1337, Val- Akita Araki, Y osokichi Aldunate 1130, Coquimbo. paraiso. Albingia Versicherungs A.G. Urriola 332, Casilla 2060, Val- Deutscher Verein Plaza Camilo Henriquez 540, Valdivia. paraiso. Deutscher Verein Union Independencia 451, Valdivia. Alemana de Vapores Kosmos, Cia Valparaiso. Diario L'Italia O'Higgins 1266, Valparaiso. Allianz und Stuttgarter Verin Esmeralda 1013, Valparaiso. Diaz Gonzalez, Alicia Madrid 944, Santiago. Versicherungs A.G. Dittmann, Bruno Prat 828, Valparaiso. Amano, Y oshitaro Funda Andalien, Concepcion. Doebbel, Federico Bandera 227, Casilla 3671, San- Anilinas y Productos Quimicos Santiago. tiago. Soc. Ltda., Cia. Generale de Dorbach Bung, Guillermo Colocolo 740, Santiago. Anker von Manstein, Fridleif Constitucion 25, San Francisco Doy Nakadi, Schiochi 21 de Mayo 287, Arica. 1801, and Maria Auxiliadora Dreher Pollitz, Boris Pasaje Matte 81, and San Antonio 998, Santiago. 527, Santiago. Asai,K. Ave. B. -

Enemigos Aliados

LOS 97 DÍAS EN QUE LA CONCERTACIÓN SALVO A PINOCHET Enemigos aliados Andrea Insunza C. Memoria para optar al título de Periodista Departamento de Estudios Mediáticos Escuela de Periodismo Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Universidad de Chile 2 A Rodrigo, mi padre. 3 Enemigos Aliados Cap. I: “El gatillo: Lepe asciende al generalato”. - Esto es indigno! Esa fue la sentencia que un par de diputados de la Democracia Cristiana (DC) compartieron el jueves 30 de octubre de 1997, tras enterarse, en la sala de sesiones de la Cámara, que el nombre del brigadier Jaime Lepe Orellana engrosaba la lista de ascensos que se efectuarían en el Ejército. La molestia de los parlamentarios tenía una justificación: el uniformado había sido relacionado con casos de violaciones a los derechos humanos cometidas bajo el régimen militar. Ya había pasado la sorpresa por el anticipado anuncio del gobierno de Eduardo Frei, que a las cinco y media de la tarde despejaba una de las incógnitas clave de la transición: el ministro de Defensa Edmundo Pérez Yoma entregaba el nombre del sucesor del general Augusto Pinochet para la Comandancia en Jefe del Ejército. Y, de paso, provocaba la irritación del oficialismo al catalogar al jefe militar como “un ejemplo de responsabilidad para quienes eligen el servicio público”. 9 Enemigos Aliados Cap. I: “El gatillo: Lepe asciende al generalato”. Pinochet –nombrado como sucesor del general Carlos Prats por el Presidente Salvador Allende el 23 de agosto de 1973– debía dejar el mando a más tardar el 11 de marzo de 1998, tras permanecer 25 años a la cabeza de la institución.