University of California Riverside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

20 · 21 2 · Edito ·

20 · 21 2 · EDITO · CHERS AMIS, CHÈRES AMIES, « Un livre a toujours deux auteurs, celui qui l’écrit et celui qui le lit ». La période que nous vivons actuellement est extrêmement particulière. En cent quarante-sept ans d’existence, l’Orchestre Colonne a déjà connu des moments Ces mots, de la plume de Jacques Salomé, résonnent en moi comme une pensée de désarroi ou de fragilité, mais jamais une telle incertitude sur l’avenir des spec- d’une vérité fondamentale. tacles vivants n’était venue à ce point inquiéter les esprits. Une œuvre littéraire a ceci de commun avec une œuvre musicale, un tableau ou un geste chorégraphique : elle ne peut vivre que dans le regard de l’autre, Alors, pour faire face à ce trouble, il faut de l’espoir : l’espoir de vous retrouver tous l’écoute de l’autre, l’émotion de l’autre... et cet «autre», fabuleux partenaire de nos ensemble, l’espoir de faire découvrir à de nouveaux auditeurs la profondeur et la émotions, c’est vous. richesse d’un son orchestral, l’espoir de continuer à œuvrer pour cette musique contemporaine en pleine mutation, et l’espoir de faire vivre à nouveau toutes les Oui, nous avons besoin du public, nous avons besoin de vous, parce que votre œuvres magnifiques que vous et nous aimons tant. énergie commune et votre enthousiasme nous subliment. Et au-delà de l’espoir, il y a une certitude : celle d’avoir la joie, pour nous musi- Au terme de ces quelques mois qui nous ont privés de votre écoute, de votre pré- ciens, de nous retrouver bientôt pour jouer à nouveau ensemble, pour vous pré- sence, la pensée de cet écrivain s’impose comme une évidence. -

CHAN 9859 Front.Qxd 31/8/07 10:04 Am Page 1

CHAN 9859 Front.qxd 31/8/07 10:04 am Page 1 CHAN 9859 CHANDOS CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 2 Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) AKG 1 In memoriam 11:28 Overture in C major in C-Dur . ut majeur Andante religioso – Allegro molto Suite from ‘The Tempest’, Op. 1 27:31 2 1 No. 1. Introduction 5:20 Andante con moto – Allegro non troppo ma con fuoco 3 2 No. 4. Prelude to Act III 1:58 Allegro moderato e con grazia 4 3 No. 6. Banquet Dance 4:39 Allegretto grazioso ma non troppo – Andante – Allegretto grazioso 5 4 No. 7. Overture to Act IV 5:00 Allegro assai con brio 6 5 No. 10. Dance of Nymphs and Reapers 4:21 Allegro vivace e con grazia 7 6 No. 11. Prelude to Act V 4:21 Andante – Allegro con fuoco – Andante 8 7 No. 12c. Epilogue 1:42 Andante sostenuto 3 CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 4 Sir Arthur Sullivan: Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ etc. Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ 36:02 Sir Arthur Sullivan would have been return to London a public performance in E-Dur . mi majeur delighted to know that the comic operas he of the complete music followed at the 9 I Andante – Allegro, ma non troppo vivace 13:21 wrote with W.S. Gilbert retain their hold on Crystal Palace Concert on 5 April 1862 10 II Andante espressivo 7:13 popular affection a hundred years after his under the baton of August Manns. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber -

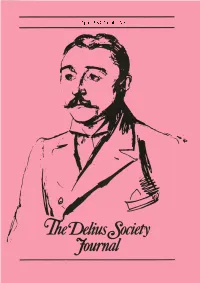

Beecham: the Delius Repertoire - Part Three by Stephen Lloyd 13

April 1983, Number 79 The Delius Society Journal The DeliusDe/ius Society Journal + .---- April 1983, Number 79 The Delius Society Full Membership £8.00t8.00 per year Students £5.0095.00 Subscription to Libraries (Journal only) £6.00f,6.00 per year USA and Canada US $17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon DMus,D Mus,Hon DLitt,D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson M Sc, Ph D (Founder Member) Sir Charles Groves CBE Stanford Robinson OBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM Meredith Davies MA, BMus,B Mus,FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon DMusD Mus VemonVernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) ChairmanChairmart RBR B Meadows 5 Westbourne House, Mount Park Road, Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 Wishing Tree Road, S1.St. Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 5053750537 Membership Secretary Miss Estelle Palmley 22 Kingsbury Road, Colindale,Cotindale,London NW9 ORR Editor Stephen Lloyd 414l Marlborough Road, Luton, Bedfordshire LU3 lEFIEF Tel: Luton (0582)(0582\ 20075 2 CONTENTS Editorial...Editorial.. 3 Music Review ... 6 Jelka Delius: a talk by Eric Fenby 7 Beecham: The Delius Repertoire - Part Three by Stephen Lloyd 13 Gordon Clinton: a Midlands Branch meeting 20 Correspondence 22 Forthcoming Events 23 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketch of Delius by Edvard Munch reproduced by kind permission of the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The quotation from In a Summer GardenGuden on page 7 is in the arrangement by Philip Heseltine included in the volume of four piano transcriptions reviewed in this issue and appears with acknowledgement to Thames Publishing and the Delius Trust. -

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906)

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906) Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man, of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, and as a perfectionist he abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His best known work is the orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'apprenti sorcier), the fame of which became a matter of irritation to Dukas. In 2011, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians observed, "The popularity of L'apprenti sorcier and the exhilarating film version of it in Disney's Fantasia possibly hindered a fuller understanding of Dukas, as that single work is far better known than its composer." Among his other surviving works are the opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariadne and Bluebeard, 1897, later championed by Toscanini and Beecham), a symphony (1896), two substantial works for solo piano (Sonata, 1901, and Variations, 1902) and a sumptuous oriental ballet La Péri (1912). Described by the composer as a "poème dansé" it depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, coming across its guardian, the Péri (fairy). Because of the very quiet opening pages of the ballet score, the composer added a brief "Fanfare pour précéder La Peri" which gave the typically noisy audiences of the day time to settle in their seats before the work proper began. Today the prelude is a favorite among orchestral brass sections. At a time when French musicians were divided into conservative and progressive factions, Dukas adhered to neither but retained the admiration of both. -

02-Pasler PM

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Deconstructing d’Indy, or the Problem of a Composer’s Reputation JANN PASLER The story of a life, like history, is an invention. notion of someone well after their death—the Certainly the biographer and historian have roles social consensus articulated by the biographer— in this invention, but so too does the composer as well as the quasi-historical judgment that for whom making music necessarily entails we make with the distance of time. This often building and maintaining a reputation. Reputa- produces the semblance of authority, the au- tion is the fruit of talents, knowledge, and thority of one manifest meaning. achievements that attract attention. It signals In reality, reputation is also the result of the renown, the way in which someone is known steps taken during a professional life to assure in public or the sum of values commonly asso- one’s existence as a composer, a process in- ciated with a person. If it does not imply public volving actions, interactions, and associations admiration, it does suggest that the public takes as well as works. This includes all efforts to an interest in the person in question. The ordi- earn credibility, respect, distinction, and finally nary sense of the word refers to the public’s prestige. As Pierre Bourdieu has pointed out, these inevitably take place in a social space, be it of teachers, friends and enemies, social and professional contacts, institutions, jobs, awards, A previous version of this article, here expanded, appeared in French as “Déconstruire d’Indy,” Revue de musicologie or critics any of whom may influence the con- 91/2 (2005), 369–400, used here by permission. -

Unraveling the Discussion of Vocal Onset

UNRAVELING THE DISCUSSION OF VOCAL ONSET: STRATEGIES FOR THE CULTIVATION OF BALANCED ONSET BASED UPON HISTORICAL AND CURRENT VOCAL PEDAGOGICAL TEACHINGS. by ABBIGAIL KATHARINE COTÉ ii A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts June 2017 iii “Unraveling the Discussion of Vocal Onset: Strategies for the Cultivation of Balanced Onset Based Upon Historical and Current Vocal Pedagogical Teachings,” a lecture- document prepared by Abbigail Katharine Coté in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This lecture- document has been approved and accepted by: Dr. Ann Tedards, Chair of the Examining Committee Date Committee in Charge: Dr. Ann Tedards, Chair Professor Milagro Vargas Dr. Marian Smith Accepted by: Leslie Straka, D.M.A. Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance iv © 2017 Abbigail Katharine Coté v CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Abbigail Coté PLACE OF BIRTH: Walnut Creek, Ca DATE OF BIRTH: October 5, 1981 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon Florida State University University of Montana DEGREES AWARDED: D.M.A in Vocal Performance, 2017, University of Oregon M.M. in Opera Production, 2012, Florida State University B.M. in Vocal Performance, 2004, University of Montana AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Vocal Performance Vocal Pedagogy Opera Direction and Production PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Graduate Teaching Fellow, University of Oregon, 2014-2017 Class Voice, Studio Voice, Lyric Diction, Introduction to Vocal Pedagogy Assistant Professor, Umpqua Community College, 2016-2017 Aural Skills, Studio Voice, and Studio Piano Executive Director, West Edge Opera, 2013 vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr.