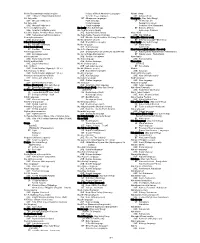

Table of Contents Item Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best of Belarus Walking Adventure Holiday

Book with confidence BBeesstt ooff BBeellaarruuss BELARUS - TRIP CODE MI DISCOVERY Why book this trip? Belarus is a country full of intrigue, with a noticeably Soviet feel thanks to its distinctive Brutalist architecture. In stark contrast explore the flora and fauna in the Berezinsky National Park. This trip appeals to those looking to discover a different side to Europe. Minsk - Explore the Belarusian capital and uncover its Soviet history and unique Brazilian-Belarusian fusion street art Castles - Admire the grandeur of the UNESCO-Listed Mir Castle, Brest Fortress and Nesvizh Castle Vitebsk - See one of Belarus's most historic and attractive towns and learn about the artist Marc Chagall 08/07/2021 08:53:49 INCLU DED TRIP STA FF TRA NSPO RT A CCO MMO DATIO N TRIP PA CE: G RO U P SIZE: MEA LS Explore Tour Bus 9 nights Full on 12 - 18 Breakfast: 9 Leader Boat comfortable hotel Lunch: 2 Driver(s) Dinner: 1 Local Guide(s) Itinerary Itineraries on some departure dates may differ, please select the itinerary that you wish to explore. DAY 1 - Join trip in Minsk Arrive in Minsk. This exciting 10-day adventure to Belarus begins in the capital city. For those arriving on time our Leader plans to meet you in the hotel reception at 8.30pm for the welcome meeting and for those that wish, there is the chance to go out for dinner. There are no other activities planned today, so you are free to arrive in Minsk at any time. If you would like to receive a complimentary airport transfer today, you'll need to arrive into Minsk National Airport (MSQ), which is around one hours' drive. -

Polish Culture Yearbook 2018

2018 POLISH CULTURE YEARBOOK 2018 POLISH CULTURE YEARBOOK Warsaw 2019 INTRODUCTION Prof. Piotr Gliński, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Culture and National Heritage 5 REFLECTIONS ON CULTURE IN POLAND 1918–2018 Prof. Rafał Wiśniewski, Director of the National Centre for Culture Poland 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 1. CELEBRATIONS OF THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF POLAND REGAINING INDEPENDENCE 17 CELEBRATIONS OF THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF POLAND REGAINING INDEPENDENCE Office of the ‘Niepodległa’ Program 18 2. CULTURE 1918–2018 27 POLISH STATE ARCHIVES Head Office of State Archives 28 LIBRARIES National Library of Poland 39 READERSHIP National Library of Poland 79 CULTURAL CENTRES Centre for Cultural Statistics, Statistical Office in Kraków 89 MUSEUMS National Institute for Museums and Public Collections 96 MUSICAL INSTITUTIONS Institute of Music and Dance 111 PUBLISHING PRODUCTION National Library of Poland 121 ARTISTIC EDUCATION Centre for Art Education 134 THEATRE IN POLAND Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute 142 IMMOVABLE MONUMENTS National Heritage Board of Poland 160 3. CULTURAL POLICY 2018 173 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT SPENDING ON CULTURE National Centre for Culture Poland 174 CINEMATOGRAPHY Polish Film Institute 181 NATIONAL MEMORIAL SITES ABROAD Department of Cultural Heritage Abroad and Wartime Losses, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage 189 POLISH CULTURAL HERITAGE ABROAD Department of Cultural Heritage Abroad and Wartime Losses, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage 196 RESTITUTION OF CULTURAL OBJECTS Department of Cultural Heritage Abroad and Wartime Losses, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage 204 DEVELOPMENT OF LIBRARY INFRASTRUCTURE AND PROGRAMMES ADDRESSED TO PUBLIC LIBRARIES Polish Book Institute 212 EXPENDITURE OF THE POLISH STATE ON CULTURE Department of Intellectual Property Rights and Media, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage 217 4. -

The Jewish Hartford European Roots (JHER) Project Was Accepting Applications for Educators to Become Thomas J

The Jewish Hartford European Roots (JHER) project was accepting applications for educators to become Thomas J. Dodd Research Center for Human Rights fellows to study Jewish life before the Holocaust. I was honored to learn that my fellowship application had been approved. I would now have the opportunity to take a trip of a lifetime to visit and study in Eastern Europe with the eminent scholar Professor Samuel Kassow. The following is a daily blog about this trip. But first a little background on the project. A couple of years ago the University of Connecticut Vice Provost for Global Affairs Daniel Weiner, Ph.D. envisioned a project that would focus on the European Jewish civilization that was destroyed by the Holocaust. In conjunction with Glenn Mitoma, Ph.D. the Director of Thomas J. Dodd Research Center for Human Rights at the University of Connecticut they sought out academic experts and community partners to launch a series of informative and enriching cultural programming. One of the primary goals is to convey the richness, vitality, and diversity of Jewish life so that educators, students and the community at large can get a glimpse into this world that was centered in Eastern Europe. The project strives to connect us with the everyday lives of the Jewish people, their culture, achievements, and challenges. This history is bittersweet and begs a number of large questions. Who gets to define it and what is its impact on contemporary Jewish life and the Western world? It also gives us greater insight into Jewish agency to respond to the catastrophe of the Shoah and how Nazi perpetrators used Jewish communal institutions to control and murder Jews en masse. -

RESISTANCE During the Holocaust

RESISTANCE during the Holocaust United States Holocaust Memorial Museum This pamphlet explores examples of armed and unarmed resis- tance by Jews and other Holocaust victims. Many courageous acts of resistance were carried out in Nazi ghettos and camps and by partisan members of national and political resistance movements across German-occupied Europe. Many individuals and groups in ghettos and camps also engaged in acts of spiritual resistance such as the continuance of religious traditions and the preservation of cultural institutions. Although resistance activities in Nazi Germany were largely ineffective and lacked broad support, some political and religious opposition did emerge. Front cover: Partisans from the Kovno ghetto in the Rudniki forest of Lithuania. 1943–44. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel Back cover: Jewish partisan musical troupe in the Naroch forest in Belorussia. 1943. Organisation des partisans combattants de la résistance et des insurgés des ghettos en Israel Inside front cover: Three Jewish partisans in the Parczew forest near Lublin. 1943–44. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel PRODUCTION OF THIS PAMPHLET IS FUNDED IN PART BY THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM’S MILES LERMAN CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF JEWISH RESISTANCE. RESISTANCERESISTANCE duringduring thethe HolocaustHolocaust Introduction 3 Obstacles to Resistance 5 Resistance in the Ghettos 9 Unarmed Resistance in Ghettos Armed Resistance: Ghetto Rebellions Resistance in Nazi Camps 23 Unarmed Resistance in the Camps Armed Resistance: Killing Center Revolts Selected -

Teaching with Defiance

TEACHING with DEFIANCE HISTORY | ETHICS | LEADERSHIP | JEWISH VALUES WRITTEN BY MAYA BERNSTEIN , EDITED IN CONSULTATION W ITH MI C HAEL BERENBAU M CONTENTS 2 Who Are the Jewish Partisans? 3 Who Are the Bielskis? 4 Introduction to this Curriculum 5 Guide CURRICULUM 6 Set-up and Procedure 7 - 8 Introduction to Units 9 - 12 History Units 13 - 16 Ethics Units 17 - 20 Leadership Units 21 - 24 Jewish Values Units 25 - 29 Partisan Testimonials 30 JPEF Films on Educator Institute DVD 31 Public Performance Licensing of Defiance This study guide made possible by Elliott and Suzanne Felson, the JPEF Gevurah Society, the Hellman Family Foundation, and Diane and Howard Wohl. ©2010 JEWISH PARTISAN EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION T EA C HING W ITH D EFIANCE Who Are the Jewish Partisans? par·ti·san noun: a member of an organized body of fighters who attack or harass an enemy, especially within occupied territory; a guerrilla During World War II, the majority of European Jews were deceived by a monstrous and meticulous disinformation campaign. The Germans and their collaborators detained mil- lions of Jews and forced them into camps, primarily by convincing them that they were going there to work. In reality, many of these so-called “work camps” were actually death camps where men, women, and children were systematically murdered. Yet approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Jews, many of whom were teenagers, escaped the Nazis to form or join organized resistance groups. These Jews are known as the Jewish partisans, and they joined hundreds of thousands of non-Jewish partisans who fought against the enemy throughout much of Europe. -

Study Guide Tuvia Bielski: Rescue Is Resistance

Study Guide Tuvia Bielski: Rescue is Resistance www.jewishpartisans.org Before his death in 1987, and the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Tuvia Bielski told his wife, In fact, their resistance was more successful Lilka, “I will be famous when then both the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and I am dead.” Bielski and Lilka the work of Schindler in both numbers of lives were living in Brooklyn, New saved and numbers of Germans killed. Tuvia York, where they seemed to Bielski was a deeply complex man: cruel and be a typical immigrant family. tender, charismatic and profane, hotheaded and Bielski, who spoke thickly composed. But he was above all passionate and accented English, worked utterly determined, possessing a connection to as a truck driver delivering the sufferings of the Jewish people that bordered plastic materials to companies on the mystical. Members of the partisan group throughout the New York remember him as super-human, riding atop a metropolitan area. Bielski was white horse in their forest enclave. “He was sent in reality the man who many by God to save Jews,” said Rabbi Beryl Chafetz, consider among the greatest who as a rabbinical student took refuge in the heroes of anti-German Bielski camp. “He wasn’t a man, he was an angel,” resistance in World War II—a said Isaac Mendelson. man who master-minded and During World War II, the majority of European led one of the most significant Jews were deceived by the German’s meticulous Jewish rescue and resistance “disinformation” campaign. The Nazis detained operations of the Holocaust. -

Pioneers and Partisans: an Oral History of Nazi Genocide in Belorussia'

H-Russia Kotljarchuk on Walke, 'Pioneers and Partisans: An Oral History of Nazi Genocide in Belorussia' Review published on Friday, April 7, 2017 Anika Walke. Pioneers and Partisans: An Oral History of Nazi Genocide in Belorussia. Oxford Oral History Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. 352 pp. $74.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-933553-4. Reviewed by Andrej Kotljarchuk (Sodertorn University)Published on H-Russia (April, 2017) Commissioned by Hanna Chuchvaha Anika Walke’s book is an important contribution to the study of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe and the history of Belarusian Jewry. Using oral history methodology, Walke explores how Soviet Jews experienced Nazi occupation and genocide in Belarus. The focus of the book is the survival of young Jewish individuals in Soviet partisan units. The author traces the personal narratives of their prewar and postwar lives. The book is composed of six chapters, an introduction, and a conclusion. In the introductory chapter, Walke presents the main approach of the book, which is focused on children’s and teenagers’ experiences during the destruction of ghettos in Minsk and other Belarusian towns and their survival in Soviet partisan units. The account is based on more than a hundred interviews conducted by the author in Minsk and St. Petersburg. The main keywords of this study are gender roles, trauma, community, memory, sexual violence, and reproductive labor in the so-called family partisan units. Special emphasis is placed on the survivors’ postwar perception of the Holocaust and partisan resistance. In chapter 1, Walke turns her attention to the oral history methodology. -

SUMMARY, No.7—8 (94-95), 2010

SUMMARY, No.7—8 (94-95), 2010 ARCHE # 7—8, 2010 The richly illustrated issue deals with last German occupation of Belarus during WWII. It has been focused on terror against civil population and its propaganda indoctrination. The issue opens with a preface by an ARCHE editor Dr. Alaksandar Paškievič. Volf Rubinčyk in his «Don’t Cast Additional Stones at Michail Savicki» discusses an old conflict, provoked by a painting by a well-known Belarusian artist Michail Savicki «The Summer Theater» from the cycle «Digits at Heart». Some Jewish activists accused the canvas and its author of anti-Semitism. Rubinčyk concludes that the charge is groundless and the topics of Jewish collaboration with Nazis have to be explored deeper. A review by Timothy Snyder ‘Caught Between Hitler & Stalin’ deals with a film directed by Edward Zwick ‘Defiance’ as well as a book ‘Defiance’ by Nechama Tec, with a foreword by Edward Zwick (Oxford University Press, 2008, 374 pp.) Both pieces are focused on the Bielski Partisan Unit in the Naliboki forest. Its creator, Tuvia Bielski, rescued more than a thousand of his fellow Jews from the Holocaust. Consequentially the Partisan Unit activity sparked the bestial Nazi response, first of all against local native people. Some Polish rightwing authors blamed Tuvia Bielski for increasing Nazi terror against Polish inhabitants of the Naliboki forest. Snyder not only examines such suggestions, but offers his critical re-assessment of the ‘Defiance’ book and movie as well as its perception by American and Polish reviewers. Alexander Pilič in his ‘Das Neue Europa in der nationalsozialistischen Propaganda — Untersuchung am Beispiel des okkupierten Weißrussland 1941—1944 (‘New Europe Concept in Nazi Propaganda: Belarus Case’) traces the origin of ‘New Europe’ concept in Nazi discourse as well as its practical use in the occupied Belarus. -

Study Guide Tuvia Bielski: Rescue Is Resistance

Study Guide Tuvia Bielski: Rescue is Resistance Before his death in 1987, Tuvia heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In fact, Bielski told his wife, Lilka, “I their resistance was more successful then both will be famous when I am the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the work of dead.” Bielski and Lilka were Schindler in both numbers of lives saved and living in Brooklyn, New York, numbers of Germans killed. Tuvia Bielski was a where they seemed to be a deeply complex man: cruel and tender, typical immigrant family. charismatic and profane, hotheaded and Bielski, who spoke thickly composed. But he was above all passionate and accented English, worked as a utterly determined, possessing a connection to truck driver delivering plastic the sufferings of the Jewish people that bordered materials on the mystical. Members of the partisan group to companies throughout the remember him as super-human, riding atop a New York metropolitan area. white horse in their forest enclave. “He was sent Bielski was in reality the man by God to save Jews,” said Rabbi Beryl Chafetz, who many consider among who as a rabbinical student took refuge in the the greatest heroes of anti- Bielski camp. “He wasn't a man, he was an angel,” German resistance in World said Isaac Mendelson. War II—a man who master- During World War II, the majority of European minded and led one of the Jews were deceived by the German's meticulous most significant Jewish rescue “disinformation” campaign. The Nazis detained and resistance operations of millions of Jews and forced them into camps, by the Holocaust. -

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Indians of North America—Languages Na'ami sheep USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine West (U.S.)—Languages USE Awassi sheep N-3 fatty acids NT Athapascan languages Naamyam (May Subd Geog) USE Omega-3 fatty acids Eyak language UF Di shui nan yin N-6 fatty acids Haida language Guangdong nan yin USE Omega-6 fatty acids Tlingit language Southern tone (Naamyam) N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ballads, Chinese USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) Na Guardis Island (Spain) Folk songs, Chinese N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) USE Guardia Island (Spain) Naar, Wadi USE Native American Music Awards Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) USE Nār, Wādī an N-acetylhomotaurine USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) Naʻar (The Hebrew word) USE Acamprosate Na-hsi (Chinese people) BT Hebrew language—Etymology N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi (Chinese people) Naar family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ranches—Montana Na-hsi language UF Nahar family N Bar Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi language Narr family BT Ranches—Montana Na Ih Es (Apache rite) Naardermeer (Netherlands : Reserve) N-benzylpiperazine USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) UF Natuurgebied Naardermeer (Netherlands) USE Benzylpiperazine Na-ion rechargeable batteries BT Natural areas—Netherlands n-body problem USE Sodium ion batteries Naas family USE Many-body problem Na-Kara language USE Nassau family N-butyl methacrylate USE Nakara language Naassenes USE Butyl methacrylate Ná Kê (Asian people) [BT1437] N.C. 12 (N.C.) USE Lati (Asian people) BT Gnosticism USE North Carolina Highway 12 (N.C.) Na-khi (Chinese people) Nāatas N.C. -

Nowogródek – the Story of Ashtetl

Nowogródek – The Story of aShtetl Yehuda Bauer racing the story of Jewish life and death in the small Jewish townships (shtetlach in Yiddish) in what is today’s west- ern Belarus and western Ukraine just prior to and during World War II is both challenging and complicated. As I have noted elsewhere, only very few monographic studies Texist on these shtetlach,1 other than those that I have published.2 The need for monographic studies on East European shtetlach, beyond the obvious historical, cultural, and social importance of these town- ships, lies in the fact that a high proportion of the Jewish population in pre-war Poland — possibly between 30 and 40 percent — lived in shtetlach. 1 Shimon Redlich, Together and Apart in Brzeżany: Poles, Jews and Ukrainians, 1919–1945 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002). Professor Omer Bartov is working on a detailed monograph on Buczacz in eastern Galicia. See also: Rose Lehman, Symbiosis and Ambivalence: Poles and Jews in a Small Galician Town (Ox- ford: Berghahn, 2001), on Jasliska in Western Galicia; Theo Richmond,Konin: A Quest (New York: Vintage, 1996); Jack Kagan, Novogrudok: The History of a Shtetl (London: Valentine Mitchell, 2006); Peter Duffy, The Bielski Brothers: The True Sto- ry of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Saved 1200 Jews, and Built a Village in the Forest (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), which also discusses Nowogródek; Daniel Mendelsohn, The Lost: A Search for Six of the Six Million (New York: HarperCollins, 2006) on Bolechow in Eastern Galicia; and Anatol Reignier, Damals in Bolechow (Munich: Btb bei Goldmann, 1997). -

Russian Emigrants and Polish Underground in 1939–1948

Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej ■ LII-SI(1) Hubert Kuberski Warsaw, Poland Russian Emigrants and Polish Underground in 1939–1948 Zarys treści: Udział emigrantów rosyjskich w II wojnie światowej jest znany, choć najczęściej kojarzony ze współpracą i zaangażowaniem po stronie państw Osi. Jednak wśród porewolucy- jnej diaspory rosyjskiej w Polsce znaleźli się ludzie, którzy zdecydowali się walczyć w szeregach polskiego podziemia w ramach Wielkiej Koalicji, przeciwstawiającej Niemcom i ich sojusznikom w latach 1939–1945. Wygnańcy rosyjscy byli zaangażowani w konspirację rożnych orientacji – od komunistycznej do narodowej. Outline of contents: The contribution of Russian emigrants to World War II is widely known, but most often it brings to mind their cooperation and engagement on the Axis side. However, there were several individuals among the post-revolution Russian diaspora in Poland, who decided to fight the Germans and their allies as part of the Polish resistance movement and the Grand Coalition 1939–45. Russian exiles were involved in conspiratorial endeavours of various orientations, from communist to nationalist ones. Słowa kluczowe: II wojna światowa, Polska w czasie II wojny światowej, biała emigracja rosyjska w Polsce, Polskie Państwo Podziemne, konspiracja w Polsce w czasie II wojny światowej, rosy- jscy emigranci w polskim podziemiu Keywords: World War II, Poland during WWII, White Russian emigration in Poland, Polish Underground State, resistance movement in Poland during WWII, Russian émigrés in the Polish resistance movement In 1931, the Second Polish Republic was home to 138,700 speakers of Russian, who constituted 0.43% of Polish citizens; the largest community lived in Wilno/Vilno (7,372 people, out of which 5,276 were Orthodox), which means they outnum- bered the Lithuanians.