Metrical Theory and Verdi's Midcentury Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7

1 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7 The History of Verdi’s La Traviata 9 Guided Listening Prelude 12 Brindisi: Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici 14 “È strano! è strano!... Ah! fors’ è lui...” and “Follie!... Sempre libera” 16 “Lunge da lei...” and “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” 18 Pura siccome un angelo 20 Alfredo! Voi!...Or tutti a me...Ogni suo aver 22 Teneste la promessa...” E tardi... Addio del passato... 24 La Traviata Resources About the Composer 26 Online Resources 29 Additional Resources Reflections after the Opera 30 The Emergence of Opera 31 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 35 Glossary 36 References Works Consulted 40 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. -

Il Trovatore

Synopsis Act I: The Duel Count di Luna is obsessed with Leonora, a young noblewoman in the queen’s service, who does not return his love. Outside the royal residence, his soldiers keep watch at night. They have heard an unknown troubadour serenading Leonora, and the jealous count is determined to capture and punish him. To keep his troops awake, the captain, Ferrando, recounts the terrible story of a gypsy woman who was burned at the stake years ago for bewitching the count’s infant brother. The gypsy’s daughter then took revenge by kidnapping the boy and throwing him into the flames where her mother had died. The charred skeleton of a baby was discovered there, and di Luna’s father died of grief soon after. The gypsy’s daughter disappeared without a trace, but di Luna has sworn to find her. In the palace gardens, Leonora confides in her companion Ines that she is in love with a mysterious man she met before the outbreak of the war and that he is the troubadour who serenades her each night. After they have left, Count di Luna appears, looking for Leonora. When she hears the troubadour’s song in the darkness, Leonora rushes out to greet her beloved but mistakenly embraces di Luna. The troubadour reveals his true identity: He is Manrico, leader of the partisan rebel forces. Furious, the count challenges him to fight to the death. Act II: The Gypsy During the duel, Manrico overpowered the count, but some instinct stopped him from killing his rival. The war has raged on. -

The Worlds of Rigoletto: Verdiâ•Žs Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Worlds of Rigoletto Verdi's Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto Mark D. Walters Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE WORLDS OF RIGOLETTO VERDI’S DEVELOPMENT OF THE TITLE ROLE IN RIGOLETTO By MARK D. WALTERS A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Mark D. Walters defended on September 25, 2007. Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise Svetla Slaveva-Griffin Outside Committee Member Stanford Olsen Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I would like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, Dennis and Ruth Ann Walters, who have continually supported me throughout my academic and performing careers. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Douglas Fisher, who guided me through the development of this treatise. As I was working on this project, I found that I needed to raise my levels of score analysis and analytical thinking. Without Professor Fisher’s patience and guidance this would have been very difficult. I would like to convey my appreciation to Professor Stanford Olsen, whose intuitive understanding of musical style at the highest levels and ability to communicate that understanding has been a major factor in elevating my own abilities as a teacher and as a performer. -

Table of Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63535-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Verdi Edited by Scott L. Balthazar Table of Contents More information Contents List of figures and table [page vii] List of examples [viii] Notes oncontributors [x] Preface [xiii] Chronology [xvii] r Part I Personal, cultural, and political context 1Verdi’s life: a thematic biography Mary Jane Phillips-Matz [3] 2The Italian theatre of Verdi’s day Alessandro Roccatagliati [15] 3Verdi, Italian Romanticism, and the Risorgimento Mary Ann Smart [29] r Part II The style of Verdi’s operas and non-operatic works 4Theforms of set pieces Scott L. Balthazar [49] 5Newcurrents in the libretto Fabrizio Della Seta [69] 6Words and music Emanuele Senici [88] 7French influences Andreas Giger [111] 8Structuralcoherence Steven Huebner [139] 9Instrumental music in Verdi’s operas David Kimbell [154] 10 Verdi’s non-operatic works Roberta Montemorra Marvin [169] r Part III Representative operas 11 Ernani: the tenor in crisis Rosa Solinas [185] 12 “Ch’hai di nuovo, buffon?” or What’s new with Rigoletto Cormac Newark [197] 13 Verdi’s Don Carlos:anoverviewoftheoperas Harold Powers [209] 14 Desdemona’s alienation and Otello’s fall Scott L. Balthazar [237] r Part IV Creation and critical reception 15 An introduction to Verdi’s working methods Luke Jensen [257] 16 Verdi criticism Gregory W.Harwood [269] [v] © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63535-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Verdi Edited by Scott L. Balthazar Table of Contents More information vi Contents Notes [282] List of Verdi’s works [309] Select bibliography and works cited [312] Index [329] © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63535-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Verdi Edited by Scott L. -

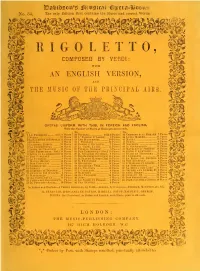

Rigoletto, Composes by Verdi: with an English Version, and the Music of the Principal Airs

No. 34. The only Edition that contains the Music and correct Words. RIGOLETTO, COMPOSES BY VERDI: WITH AN ENGLISH VERSION, AND THE MUSIC OF THE PRINCIPAL AIRS IjIBfipf l^g UNIFORM WITH THIS, IN FOREICN AND ENCLISH, With the Number of Pieces of Music printed in each. No. No. 1 Le Peophete with 9 Pieces 22 Fidklio with 5 Pieces 43 Crispino e la Comare 7 2 Noema 1- Pieces 23 L' Elisiee d'Amore 9 Pieces 44 Luisa Miller 14 3 IlBaebierediSivigliaH Pieces 24 Les Huguenots 10 Pieces 45 Marta 10 4 Otello 8 Pieces 25 I Puritani io Pieces 46 Zampa 8 5 Lucrezia Borgia 15 Pieces 20 Romeo e Giulietta 7 Pines 47 Macbeth 12 La Cekebbntola 10 Pieces 27 La Gazza Ladra 11 Pieces 48 II Giuramento 15 7 Linda di Chamouni ...10 Pieces 2S PiPEi.io (German) 5 Pieces 40 Matrimonio Segreto 10 8 Lek Fbeischtjtz (Hal.) 10 Pieces 2» Der FREiscnuiz (Ger.) lo Pieces 50 Orfeo e Eurydice 8 9 LUCIA DI LamMEEMOOR 10 Pieces so II Seraglio (German)... 7 Pieces > 51 Ballo in Maschera ...12 10 Don Pasquale 6 Pieces 31 Die Zaubeeflote (Ger) 10 Pieces ! 52 I Lombardi 14 11 La Favorita 8 Pieces 32 II Flauto Magico (Ita) 10 Pieces 63 La Forza del Destino 9 12 Medea (Mayer) 10 Pieces 33 II Trovatore 16 Pieces 64 Don Bucefalo 4 18 ]>cm Giovanni 11 Pieces 34, KlGOLETTO 10 Pieces 55 L'Italiana in Algeri... 8 | 50 Precauzioni 8 1 1 Semiramide 10 Pieces 35 Guglielmo Teli. 6 Pieces Le là Kunani 10 Pieces 30 La Traviata 12 Pieces 57 La Donna del Lago ...li Pieces I 8 Pieces 58 Orphee aux Enfees, Fr 9 l'ieres 16 Koiikkto II Diavolo .. -

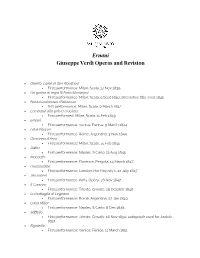

Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Operas and Revision

Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Operas and Revision • Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio • First performance: Milan, Scala, 17 Nov 1839. • Un giorno di regio (Il Finto Stanislao) • First performance: Milan, Scala, 5 Sept 1840; alternative title used 1845 • Nabuccodonosor (Nabucco) • first performance: Milan, Scala, 9 March 1842 • Lombardi alla prima crociata • First performed: Milan, Scala, 11 Feb 1843 • Ernani • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 9 March 1844 • I due Foscari • First performance: Rome, Argentina, 3 Nov 1844 • Giovanna d’Arco • First performance: Milan, Scala, 15 Feb 1845 • Alzira • First performance: Naples, S Carlo, 12 Aug 1845 • Macbeth • First performance: Florence, Pergola, 14 March 1847 • I masnadieri • First performance: London, Her Majesty’s, 22 July 1847 • Jérusalem • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 26 Nov 1847 • Il Corsaro • First performance: Trieste, Grande, 25 October 1848 • La battaglia di Legnano • First performance: Rome, Argentina, 27 Jan 1849 • Luisa Miller • First performance: Naples, S Carlo, 8 Dec 1848 • Stiffelio • First performance: Trieste, Grnade, 16 Nov 1850; autograph used for Aroldo, 1857 • Rigoletto • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 11 March 1851 • Il trovatore • First performance: Rome, Apollo, 19 Jan 1853 • La Traviata • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 6 March 1853 • Les vêpres siciliennes • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 13 June 1855 • Simon Boccanegra • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 12 March 1857, rev. version Milan, Scala, 24 March 1881 • Aroldo • First performance: Rimini, Nuovo, 16 Aug 1857 • Un ballo in maschera • First performance: Rome, Apollo, 17 Feb 1859 • La forza del destino • First performance: St Petersburg, Imperial, 10 Nov 1862, rev. version Milan, Scala, 27 Feb 1869 • Don Carlos • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 11 March 1867, rev. -

I DUE FOSCARI Musica Di GIUSEPPE VERDI

I DUE FOSCARI Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI FESTIVAL VERDI 2019 2019 FONDAZIONE Socio fondatore Comune di Parma Soci benemeriti Fondazione Cariparma Fondazione Monte di Parma Presidente Sindaco di Parma Federico Pizzarotti Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Ilaria Dallatana Vittorio Gallese Antonio Giovati Alberto Nodolini Direttore generale Anna Maria Meo Direttore musicale del Festival Verdi Roberto Abbado Direttore scientifico del Festival Verdi Francesco Izzo Curatrice Verdi Off Barbara Minghetti Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Marco Pedretti Angelica Tanzi Il Festival Verdi è realizzato grazie al contributo di Major partner Main partners Media partner Main sponsor Sponsor Advisor Con il supporto di Con il contributo di Con il contributo di Partner istituzionali Partner artistici Partner istituzionali Partner artistici Festival Verdi è partner di Festival Verdi ha ottenuto il Festival Verdi è partner di Festival Verdi ha ottenuto il Con il contributo di Sostenitori Partner istituzionali Partner artistici Tour operator Radio ufficiale Sostenitori tecnici Festival Verdi è partner di Festival Verdi ha ottenuto il I due Foscari Tragedia lirica in tre atti su libretto di Francesco Maria Piave, da Byron Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI L’opera in breve Scelto come soggetto per l’opera da rappresentare al Teatro Argentina di Roma nell’inverno 1844, sulla base del contratto con l’impresario Alessandro Lanari del 29 febbraio di quell’anno, il poema The two Foscari di George Gordon Byron (1821) ben si prestava agli occhi di Verdi per proseguire lungo quel percorso drammatico incentrato sui conflitti personali e intrapreso con Ernani a Venezia, che gli aveva permesso di dissociarsi dall’etichetta del dramma corale a cui l’aveva legato la popolarità di Nabucco e Lombardi. -

One of Opera's Greatest Hits! Teacher's Guide and Resource Book

One of opera’s greatest hits! Teacher’s Guide and Resource Book 1 Dear Educator, Welcome to Arizona Opera! We are thrilled that you and your students are joining us for Rigoletto, Verdi’s timeless, classic opera. At Arizona Opera, we strive to help students find and explore their voices. We believe that providing opportunities to explore the performing arts allows students to explore the world around them. Rigoletto is a great opera to introduce students to the world of opera. By preparing them for this opera, you are setting them up to get the most out of their experience of this important, thrilling work. This study guide is designed to efficiently provide the information you need to prepare your students for the opera. At the end of this guide, there are a few suggestions for classroom activities that connect your students’ experience at the opera to Arizona College and Career Ready Standards. These activities are designed for many different grade levels, so please feel free to customize and adapt these activities to meet the needs of your individual classrooms. Parking for buses and vans is provided outside Symphony Hall. Buses may begin to arrive at 5:30pm and there will be a preshow lecture at 6:00pm. The performance begins at 7:00pm. Again, we look forward to having you at the opera and please contact me at [email protected] or at (602)218-7325 with any questions. Best, Joshua Borths Education Manager Arizona Opera 2 Table of Contents About the Production Audience Etiquette: Attending the Opera……………………………………………………………Pg. -

I Vespri Siciliani in Portogallo (1857-1863): Recezione Verdiana E Rifiuto Della Storia Nazionale

I Vespri siciliani in Portogallo (1857-1863): recezione verdiana e rifiuto della storia nazionale Luísa Cymbron (CESEM-Universidade Nova de Lisboa) Il 12 marzo 1857 andò in scena al Teatro S. Carlos di Lisbona, in traduzione italiana, il grand opéra che Verdi aveva scritto per l’Académie Imperiale de Musique: I Vespri siciliani. Verdi era in quegli anni, secondo le parole di un critico, «il maestro prediletto della società lisbonense»1 e infatti la maggior parte delle stagioni del teatro italiano della capitale portoghese, a partire da quella del 1853-54, si aprirono con una delle sue opere. Inoltre, nel corso del decennio 1850-60, i ruoli dei due principali teatri portoghesi – il S. Carlos di Lisbona e il S. João di Oporto – si invertirono: se durante gli anni Quaranta le opere di Verdi arrivavano a Oporto dopo essere state presentate a Lisbona, adesso gli impresari del S. João cercavano di anticipare la capitale ricorrendo il più delle volte a versioni ‘pirata’ (orchestrate da musicisti locali sulla base di spartiti per canto e pianoforte) o a quelle che, per adattarsi alla censura dei diversi stati della penisola italiana, avevano subito modifiche nell’ambientazione, trasferendo l’azione in scenari geografici e temporali diversi.2 A Lisbona si cercava invece di presentare le versioni originali, il che comportava un po’ di ritardo nelle prime: delle dieci opere di Verdi che avevano debuttato negli anni Cinquanta, cinque erano state ascoltate al S. João prima che al S. Carlos e due, Stiffelio e L’assedio di Arlem (la versione censurata di La battaglia di Legnano), non erano mai state rappresentate a Lisbona. -

La Battaglia Di Legnano

LA BATTAGLIA DI LEGNANO Tragedia lirica. testi di Salvadore Cammarano musiche di Giuseppe Verdi Prima esecuzione: 27 gennaio 1849, Roma. www.librettidopera.it 1 / 33 Informazioni La battaglia di Legnano Cara lettrice, caro lettore, il sito internet www.librettidopera.it è dedicato ai libretti d©opera in lingua italiana. Non c©è un intento filologico, troppo complesso per essere trattato con le mie risorse: vi è invece un intento divulgativo, la volontà di far conoscere i vari aspetti di una parte della nostra cultura. Motivazioni per scrivere note di ringraziamento non mancano. Contributi e suggerimenti sono giunti da ogni dove, vien da dire «dagli Appennini alle Ande». Tutto questo aiuto mi ha dato e mi sta dando entusiasmo per continuare a migliorare e ampliare gli orizzonti di quest©impresa. Ringrazio quindi: chi mi ha dato consigli su grafica e impostazione del sito, chi ha svolto le operazioni di aggiornamento sul portale, tutti coloro che mettono a disposizione testi e materiali che riguardano la lirica, chi ha donato tempo, chi mi ha prestato hardware, chi mette a disposizione software di qualità a prezzi più che contenuti. Infine ringrazio la mia famiglia, per il tempo rubatole e dedicato a questa attività. I titoli vengono scelti in base a una serie di criteri: disponibilità del materiale, data della prima rappresentazione, autori di testi e musiche, importanza del testo nella storia della lirica, difficoltà di reperimento. A questo punto viene ampliata la varietà del materiale, e la sua affidabilità, tramite acquisti, ricerche in biblioteca, su internet, donazione di materiali da parte di appassionati. Il materiale raccolto viene analizzato e messo a confronto: viene eseguita una trascrizione in formato elettronico. -

Press Release Philharmonia Records Verdi

Philharmonia Records c/o Opernhaus Zürich Bettina Auge Pressereferentin Falkenstrasse 1 CH-8008 Zürich T + 41 44 268 64 34 [email protected] Zürich, 8. September 2017 Philharmonia Records presents: Giuseppe Verdi – Ouvertures and Preludes Giuseppe Verdi composed over 30 operas, though only about half of them are still regularly staged. For the latest studio recording with the Philharmonia Zürich, Fabio Luisi has cho- sen overtures and preludes from Verdi’s whole creative period. Next to popular masterpieces like the overture to «La forza del destino», the selection ranges from the earliest works by Verdi, which strongly remind of Rossini and Donizetti, over exceptional preludes he wrote for «Macbeth» or «La traviata» for example, to rarely performed overtures such as «I vespri sicil- iani» or «La battaglia di Legnano». A special highlight on this recording is the long version of the overture to «Aida», which is never heard in combination with opera. Furthermore, the ballet music for the French version of «Don Carlos» also found its way onto the album. Thus, the compilation unites pieces that belong to the day-to-day repertoire of the Philharmonia Zurich with those that are also rarities to orchestra musicians. Available worldwide as of now. CD 1 CD 2 1) La forza del destino 1) Luisa Miller 2) Aida 2) La battaglia di Legnano 3) Don Carlos 3) Il corsaro 4) Un ballo in maschera 4) I masnadieri 5) I vespri siciliani 5) Macbeth 6) La traviata 6) Giovanna d’Arco 7) Stiffelio 7) Ernani 8) Jerusalem 9) Nabucco 10) Un giorno di regno 11) Oberto Running time: 127.44 min Please find enclosed your personal review copy. -

La Traviata March 5 – 13, 2011

O p e r a B o x Teacher’s Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Giuseppe Verdi – a biography ...............................50 Catalogue of Verdi’s Operas . .52 Background Notes . .54 2 0 1 0 – 2 0 1 1 S E A S O N The Real Traviata . .58 World Events in 1848 and 1853 . .64 ORPHEUS AND History of Opera ........................................68 URYDICE History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .79 E SEPTEMBER 25 – OCTOBER 3, 2010 The Standard Repertory ...................................83 Elements of Opera .......................................84 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................88 CINDERELLA OCTOBER 30 – NOVEMBER 7, 2010 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................94 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .97 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .100 MARY STUART Evaluation . .103 JANUARY 29 – FEBRUARY 6, 2011 Acknowledgements . .104 LA TRAVIATA MARCH 5 – 13, 2011 WUTHERING mnopera.org HEIGHTS APRIL 16 – 23, 2011 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards.