Guide to Good Hygienic Practices for Packaged Water in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(WHO) Report on Microplastics in Drinking Water

Microplastics in drinking-water Microplastics in drinking-water ISBN 978-92-4-151619-8 © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Microplastics in drinking-water. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requests for commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing. -

Sensitive Determination of Iron in Drinking Water, Mineral Water, Groundwater, and Spring Water Using Rapid Photometric Tests

ENVIRONMENTAL Sensitive Determination of Iron in Drinking Water, Mineral Water, Groundwater, and Spring Water Using Rapid Photometric Tests Katrin Schwind, Application Scientist, Analytical Point-of-Use R&D, [email protected] Gunter Decker, Senior Global Product Manager, Analytical Point-of-Use Analytics | Photometry, [email protected] The quality of drinking water is regulated by a variety The determination of iron using the 1,10-phenanthroline of guidelines, such as the EU Council Directive 98/831,2 method according to APHA 3500-Fe B and DIN 38406-1 and WHO guideline.3 The key principles used to define enables photometric measurement down to a level of these limits consider both health hazards and sensory 0.01 mg/L, which is entirely sufficient for many samples.9 and technical reasons. Iron, for example, does not exhibit a risk for health in concentrations usually found If lower LOQs are required, the triazine method can in drinking water.2,3 However, increased concentrations be chosen. In this method, all iron ions are reduced to of iron result in the formation of iron hydroxide iron (II) ions. These react in a thioglycolate-buffered products, which can form deposits in water pipe medium containing a triazine derivative to form a systems and a brown discoloration of the water.4 red-violet complex, which is subsequently determined photometrically.10 Using a 100 mm cell and the Prove To ensure the supply of clear and colorless water, 600 UV-VIS spectrometer, LOQs for iron as low as country-specific limits have been set for drinking 0.0025 mg/L can be achieved. -

1 Chapter 8130 Department of Revenue Sales and Use Taxes

1 CHAPTER 8130 DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE SALES AND USE TAXES GENERAL PROVISIONS 8130.0110 SCOPE AND INTERPRETATION. 8130.0200 SALE BY TRANSFER OF TITLE. 8130.0400 LEASES. 8130.0500 LICENSE TO USE. 8130.0600 CONSIDERATION. 8130.0700 PRODUCING, FABRICATING, PRINTING, OR PROCESSING OF PROPERTY FURNISHED BY CONSUMER. 8130.0900 ENTERTAINMENT. 8130.1000 LODGING. 8130.1100 UTILITIES AND RESIDENTIAL HEATING FUELS. 8130.1200 SALES OF BUILDING MATERIAL, SUPPLIES, OR EQUIPMENT. 8130.1500 EXEMPTION FOR PROPERTY TAKEN IN TRADE. 8130.1700 DEDUCTIONS ALLOWABLE IN COMPUTING SALES PRICE. 8130.1800 GROSS RECEIPTS DEFINED; METHOD OF REPORTING. 8130.1900 RETAILER AND SELLER. ADMINISTRATION OF SALES AND USE TAXES 8130.2300 IMPOSITION OF SALES TAX. 8130.2500 APPLICATION FOR PERMIT TO MAKE RETAIL SALES. 8130.2700 REINSTATEMENT OF REVOKED PERMITS. 8130.3100 CONTENT AND FORM OF EXEMPTION CERTIFICATE. 8130.3200 NONEXEMPT USE OF PURCHASE OBTAINED WITH EXEMPTION CERTIFICATE. 8130.3300 FUNGIBLE GOODS FOR WHICH EXEMPTION CERTIFICATE GIVEN. 8130.3400 DIRECT PAY AUTHORIZATION PROCEDURE. 8130.3500 MOTOR CARRIERS IN INTERSTATE COMMERCE. 8130.3800 IMPOSITION OF USE TAX. 8130.3900 LIABILITY FOR PAYMENT OF USE TAX. 8130.4000 COLLECTION OF TAX AT TIME OF SALE. 8130.4300 PROPERTY BROUGHT INTO MINNESOTA. 8130.4400 CREDIT AGAINST USE TAX. EXEMPTIONS 8130.4700 PREPARED FOOD, CANDY, AND SOFT DRINKS. 8130.4705 FOOD SOLD WITH EATING UTENSILS. 8130.5300 PETROLEUM PRODUCTS. 8130.5500 AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION. 8130.5550 SPECIAL TOOLING. 8130.5600 PUBLICATIONS. Copyright ©2015 by the Revisor of Statutes, State of Minnesota. All Rights Reserved. 8130.0110 SALES AND USE TAXES 2 8130.5700 SALES TO EXEMPT ENTITIES, THEIR EMPLOYEES, OR AGENTS. -

Difference Between Mineral Water and Spring Water Strictly Speaking, Water Is Water

Difference between Mineral Water and Spring Water Strictly speaking, water is water. That is to say, all water on Earth is a compound of two hydrogen and one oxygen molecule. The difference between various types of bottled waters lies mainly in where the source is located and what processes the water goes through before it is sold to consumers. Not all bottled waters are recommended for drink- ing, so it is important to know the difference if your health plan includes increasing water intake or avoiding certain types of beverages. Some types of bottled water, such as well or spring, get their designation from their origi- nal source. Mineral water must contain a specified amount of trace minerals naturally before it can be sold. Distilled or purified water must be put through a filtration or me- chanical process in order to remove contaminants and minerals. Some water types may actually fit into several different categories- distilled water, for example, is also purified by definition. Spring and well waters make excellent refreshments during and afterexercise, but distilled water lacks trace minerals and may not have a satisfying taste. Mineral water may have a natural sparkle and refreshing taste, but a little may go a long way. Here's a closer look at each type of water and how each one fits in an everyday world. 1. Well water. Well water could be the source of other types of consumable bottle waters such as 'drinking' or regular tap water. The main definition of 'well water' is water that has been stored in permeable rocks and soil. -

The Influence of Preservation Methods of the Color and Other Quality Attributes of Green Beans (Fhaseolus Vulgaris L.)

T This dissert itlon has been microfilmed e> actlyab received 70-6793 HILDEBOLT, William Morton, 1943- THE INFLUENCE OF PRESERVATION METHODS OF THE COLOR AND OTHER QUALITY ATTRIBUTES OF GREEN BEANS (FHASEOLUS VULGARIS L.) The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Food Technology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan TIE INFLUENCE OF PRESERVATION METHODS OF THE COLOR AND OTHER j . QUALITY ATTRIBUTES OF GREEN BEANS (PHASEOLUS VULGARIS L.) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William Morton Hildebolt, M.S. ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by fa ftJUs-Q.-hrdtf Adviser Department of Horticulture and Forestry ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his appreciation and gratitude to the following: my wife, Sandra, and my family, for their constant encouragement, understanding, and assistance throughout my graduate studies. Ify adviser, Dr. Wilbur A. Gould, for his guidance, assistance, • and learned counsel. Dr. Jean R. Geisman, for his suggestions and guidance in the final preparation of this manuscript. Dr. C. Richard Weaver and the Statistics Laboratory of the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Wooster, Ohio, for their help in analyzing the results of this project. The staff and many students of the Food Processing and Tech nology Division, Department of Horticulture and Forestry, for their help in the processing of the many samples required for this study, and special thanks to Dr. David E. Crean for his technical assistance. ii VITA December 7, 1943 . Born - Richmond, Indiana 1966 .............. B.S. in Food Technology, The Ohio State University, Columbus,. -

13. Nutrient Minerals in Drinking Water: Implications for the Nutrition

13. NUTRIENT MINERALS IN DRINKING WATER: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE NUTRITION OF INFANTS AND YOUNG CHILDREN Erika Sievers Institute of Public Health North Rhine Westphalia Munster, Germany ______________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION The WHO Global Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding emphasizes the importance of infant feeding and promotes exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life. In infants who cannot be breast-fed or should not receive breast milk, substitutes are required. These should be a formula that complies with the appropriate Codex Alimentarius Standards or, alternatively, a home-prepared formula with micronutrient supplements (1). Drinking water is indispensable for the reconstitution of powdered infant formulae and needed for the preparation of other breast-milk substitutes. As a result of the long-term intake of a considerable volume in relation to body weight, the concentrations of nutrient minerals in drinking water may contribute significantly to the total trace element and mineral intake of infants and young children. This is especially applicable to formula-fed infants during the first months of life, who may be the most vulnerable group affected by excessive concentrations of nutrients or contaminants in drinking water. Defining essential requirements of the composition of infant formulae, the importance of the quality of the water used for their reconstitution has been acknowledged by the Scientific Committee on Food, SCF, of the European Commission (2). Although it was noted that the mineral content of water may vary widely depending upon its source, the optimal composition remained undefined. Recommendations for the composition of infant formulae refer to total nutrient content as prepared ready for consumption according to manufacturer’s instructions. -

Bottled Water Vs. Tap Water

FEDERATION OF AMERICAN CONSUMERS AND TRAVELERS - NEWS RELEASE - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Which is Safer -- Bottled Water or Water from the Tap? EDWARDSVILLE, IL, January 11, 2010 - Vicki Rolens, Managing Director of the Federation of American Consumers (FACT), has sought information concerning the relative safety and purity of bottled water. “Bottled water has become extremely popular in recent years,” says Rolens, “which has inevitably led to may questions about its advantages and disadvantages, and we were hoping to find some definitive answers for our members.” According to the Food and Drug Administration, there are seven ways bottled water can be labeled: 1. Artesian Water / Artesian Well Water: Bottled water from a well that taps a confined aquifer (a water-bearing underground layer of rock or sand) in which the water level stands at some height above the top of the aquifer. 2. Drinking Water: Drinking water is another name for bottled water. Accordingly, drinking water is water that is sold for human consumption in sanitary containers and contains no added sweeteners or chemical additives (other than flavors, extracts or essences). It must be calorie-free and sugar-free. Flavors, extracts or essences may be added to drinking water, but they must comprise less than one- percent-by-weight of the final product or the product will be considered a soft drink. Drinking water may be sodium-free or contain very low amounts of sodium. 3. Mineral Water: Bottled water containing not less than 250 parts per million total dissolved solids may be labeled as mineral water. Mineral water is distinguished from other types of bottled water by its constant level and relative proportions of mineral and trace elements at the point of emergence from the source. -

Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality FIRST ADDENDUM to THIRD EDITION Volume 1 Recommendations WHO Library Cataloguing-In-Publication Data World Health Organization

Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality FIRST ADDENDUM TO THIRD EDITION Volume 1 Recommendations WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality [electronic resource] : incorporating first addendum. Vol. 1, Recommendations. – 3rd ed. Electronic version for the Web. 1.Potable water – standards. 2.Water – standards. 3.Water quality – standards. 4.Guidelines. I. Title. ISBN 92 4 154696 4 (NLM classification: WA 675) © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

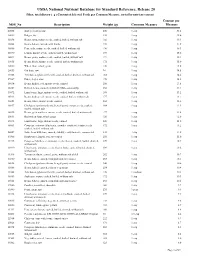

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20 Fiber, total dietary( g ) Content of Selected Foods per Common Measure, sorted by nutrient content Content per NDB_No Description Weight (g) Common Measure Measure 20005 Barley, pearled, raw 200 1 cup 31.2 20012 Bulgur, dry 140 1 cup 25.6 16038 Beans, navy, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 182 1 cup 19.1 16008 Beans, baked, canned, with franks 259 1 cup 17.9 16086 Peas, split, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 196 1 cup 16.3 16070 Lentils, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 198 1 cup 15.6 16043 Beans, pinto, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 171 1 cup 15.4 16015 Beans, black, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 172 1 cup 15.0 20080 Wheat flour, whole-grain 120 1 cup 14.6 20033 Oat bran, raw 94 1 cup 14.5 11008 Artichokes, (globe or french), cooked, boiled, drained, without salt 168 1 cup 14.4 09087 Dates, deglet noor 178 1 cup 14.2 16034 Beans, kidney, red, mature seeds, canned 256 1 cup 13.8 16103 Refried beans, canned (includes USDA commodity) 252 1 cup 13.4 16072 Lima beans, large, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 188 1 cup 13.2 16033 Beans, kidney, red, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 177 1 cup 13.1 16051 Beans, white, mature seeds, canned 262 1 cup 12.6 16057 Chickpeas (garbanzo beans, bengal gram), mature seeds, cooked, 164 1 cup 12.5 boiled, without salt 16025 Beans, great northern, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 177 1 cup 12.4 20011 Buckwheat flour, whole-groat 120 1 cup 12.0 16073 Lima -

The Cleanliness of Reusable Water Bottles: How Contamination Levels Are Affected by Bottle Usage and Cleaning Behaviors of Bottle Owners

PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE Xiaodi Sun,1 Jooho Kim,2* Carl Behnke,1 Barbara Food Protection Trends, Vol 37, No. 6, p. 392–402 1 3 3 Copyright© 2017, International Association for Food Protection Almanza, Christine Greene, Jesse Miller and 6200 Aurora Ave., Suite 200W, Des Moines, IA 50322-2864 Bryan Schindler3 1The School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Purdue University, 900 W. State St., West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA 2Hart School of Hospitality, Sport and Recreation Management, James Madison University, MSC 2305, Harrisonburg, VA 22807, USA 3NSF International, 789 North Dixboro Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48105, USA The Cleanliness of Reusable Water Bottles: How Contamination Levels are Affected by Bottle Usage and Cleaning Behaviors of Bottle Owners ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Reusable water bottles are growing in popularity, but Demand for bottled water has consistently increased consumers regularly refill bottles without a corresponding in recent years, making bottled water the fastest growing effort at cleaning them. If the difficulties associated with segment of the non-alcoholic beverage market worldwide various bottle designs and materials are added in, it is (11). However, massive consumption of water in disposable clear that improperly cleaned water bottles may present bottles has been connected to increased pollution and a potential contamination risk and thus be a risk for landfill waste. The EPA(35) reported that each year foodborne illness. The purpose of this study was to measure Americans throw away about 28 billion bottles and jars; contamination levels of water bottles that are in use and to notably, only 26% of plastic bottles were recycled. The investigate bottle usage and cleaning behaviors by collecting environmental cost associated with bottled water has led to survey data from the bottle owners. -

The Mineral Content of US Drinking and Municipal Water

The Mineral Content of US Drinking and Municipal Water Pamela Pehrsson, Kristine Patterson, and Charles Perry USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Human Nutrition Research Center, Nutrient Data Laboratory, Beltsville, MD Abstract Methods and Materials Table 1. Mineral content of water Figure 2. Mineral Content of Water Samples by Region The mineral composition of tap water may contribute significant samples (mg/100g) 8 amounts of some minerals to dietary intake. The USDA’s Nutrient Step 1. Develop sampling design 2.5 Avg Pickup 1 • US population ordered by county and divided into 72 equal DRI* Magnesium Pickup 1 7 Pickup 2 Data Laboratory (NDL) conducted a study of the mineral content of Pickup 2 Calcium Mean Median Min Max mg in 2.0 *Mean +/- SEM residential tap water, to generate new current data for the USDA zones, 1 county per zone selected, probability minimum mg/day 6 2 liters (male 31-50y) National Nutrient Database. Sodium, potassium, calcium, replacement, 2 locations (residential, retail outlets) selected in 5 Ca 3.0 2.7 0.0 10.0 61 1000 1.5 magnesium, iron, copper, manganese, phosphorus, and zinc were each sampled county (Figure 1) 4 determined in a nationally representative sampling of drinking water. Cu 0.0098 0.0017 ND 0.4073 0.20 0.90 n=25 1.0 g /100 Ca mg 3 n=25 Step 2. Obtain study approval mg Mg / 100g n=26 n=26 The sampling method involved: serpentine ordering of the US Fe n=5 n=40 • Federal Register announcement and approval by OMB 0.002 0.0003 ND 0.065 0.04 8 n=9 2 n=26 population by census region, division, state and county; division of 0.5 n=40 n=5 K 0.5 0.2 ND 20.4 9.8 4700 n=2 1 n=9 process, survey and incentives n=26 n=2 n=10 the population into 72 equal size zones; and random selection of one n=10 0 Mg 0.9 0.8 0.0 4.6 19 420 0.0 ll st county per zone and two residences per county (144 locations). -

Initial Report on the Independent Review of the Impacts of the Bottled

Initial report on the Independent review of the impacts of the bottled water industry on groundwater resources in the Northern Rivers region of NSW NSW Chief Scientist & Engineer 1 February 2019 Errata Grammatical and formatting revisions: ‘is’ to ‘has’ (pg. iv); added ‘, which will’ (pg. v); ‘source’ to ‘sources’ (pg. 15); ‘Office of’ to ‘-‘ (pg. 18); removed repetitive word ‘relative’ (pg. 20); ‘5.3.1’ to ‘3.2.1’, ‘5.3.2’ to ‘3.2.2’ and ‘5.3.3’ to ‘3.2.3’ (pg. 33); ‘then’ to ‘Chapter 3’ (pg. 74) pg. 32 – revised ‘licensed for extraction’ to ‘extracted’ pg. 33 – revised ‘extraction rate’ to ‘total water access rights’ pg. 33 – revised ‘estimated’ to ‘calculated’ Chap 3 – ‘planned environmental water (PEW)’ changed to ‘recharge amount reserved for the environment (RRE)’ Addenda pg. 30 Table 3 – added word ‘Supporting‘ to column 3 pg. 33 – added ’80 percent of’ Corrigendum pg. 33 – removed sentence - ‘Where extraction is at or above the LTAAEL allocations can typically be traded within the groundwater source/management area(s).’ www.chiefscientist.nsw.gov.au/reports/independent-review-of-impacts-of-the-bottled-water-industry- on-groundwater-resources-in-the-northern-rivers-region-of-nsw The Hon. Niall Blair MLC Minister for Primary Industries Minister for Regional Water Minister for Trade and Industry 52 Martin Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 1 February 2019 Dear Minister Independent review of the impacts of the bottled water industry on groundwater resources in the Northern Rivers region of NSW In November 2018, you requested that I undertake an independent review of the impacts of the bottled water industry on groundwater resources in the Northern Rivers region of NSW.