Diplomatic Solutions: Land Use in Anglo-Saxon Worcestershire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 09/03/2020 to 13/03/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 20/00090/TPOA Location: The Manor House, 4 High Street, Badsey, Evesham, WR11 7EW Proposal: Horsechestnut - To be removed. Reason - Roots are blocking the drains, tree has been pollarded in the past so is a bad shape and it is diseased. Applicant will plant another tree further from the house. Decision Date: 11/03/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Ms Elizabeth Noyes Agent: Ms Elizabeth Noyes The Manor House The Manor House 4 High Street 4 High Street Badsey Badsey Evesham Evesham WR11 7EW WR11 7EW Parish: Badsey Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Sally Griffiths Expiry Date: 11/03/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565308 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/00236/HP Location: Hopwood, Prospect Gardens, Elm Road, Evesham, WR11 3PX Proposal: Extension to form porch Decision Date: 13/03/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr & Mrs Asbury Agent: Mr Scott Walker Hopwood The Studio Prospect Gardens Bluebell House Elm Road Station Road Evesham Blackminster WR11 3PX Evesham WR11 7TF Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Oliver Hughes Expiry Date: 31/03/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565191 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 17 Application No: 20/00242/ADV Location: Cavendish Park Care Home, Offenham Road, Evesham, WR11 3DX Proposal: Application -

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Croome Collection Coventry Family History

Records Service Croome Collection Coventry Family History George William Coventry, Viscount Deerhurst and 9th Earl of Coventry Born 1838, the first son of George William (Viscount Deerhurst) and his wife Harriet Anne Cockerell. After the death of their parents, George William and his sister, Maria Emma Catherine (who later married Gerald Henry Brabazon Ponsonby), were brought up at Seizincote, but they visited Croome regularly. He succeeded as Earl in 1843, aged only 5 years old. During his minority his great-uncle William James (fifth son of the 7th Earl and his wife 'Peggy') took responsibility for the estate, with assistance from his guardians and trustees: Richard Temple of the Nash, Kempsey, Worcestershire and his grandfather, Sir Charles Cockerell. When the 9th Earl came of age at 21 he let William James and his wife Mary live at Earls Croome Court rent- free for the rest of their lives. George William married Lady Blanche Craven (1842-1930), the third daughter of William Craven, 2nd Earl Craven of Combe Abbey, Warwickshire. Together they had five sons: George William, Charles John, Henry Thomas, Reginald William and Thomas George, and three daughters: Barbara Elizabeth, Dorothy and Anne Blanche Alice. In 1859 George William was elected as president of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). In 1868 he was invited to be the first Master of the new North Cotswold Hunt when the Cotswold Hunt split. He became a Privy Councillor in 1877 and served as Captain and Gold Stick of the Corps of Gentleman-at-Arms from 1877-80. George William served as Chairman of the County Quarter Sessions from 1880-88. -

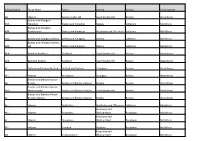

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

Index to Aerial Photographs in the Worcestershire Photographic Survey

Records Service Aerial photographs in the Worcestershire Photographic Survey Aerial photographs were taken for mapping purposes, as well as many other reasons. For example, some aerial photographs were used during wartime to find out about the lie of the land, and some were taken especially to show archaeological evidence. www.worcestershire.gov.uk/records Place Description Date of Photograph Register Number Copyright Holder Photographer Abberley Hall c.1955 43028 Miss P M Woodward Abberley Hall 1934 27751 Aerofilms Abberley Hills 1956 10285 Dr. J.K.S. St. Joseph, Cambridge University Aldington Bridge Over Evesham by-Pass 1986 62837 Berrows Newspapers Ltd. Aldington Railway Line 1986 62843 Berrows Newspapers Ltd Aldington Railway Line 1986 62846 Berrows Newspapers Ltd Alvechurch Barnt Green c.1924 28517 Aerofilms Alvechurch Barnt Green 1926 27773 Aerofilms Alvechurch Barnt Green 1926 27774 Aerofilms Alvechurch Hopwood 1946 31605 Aerofilms Alvechurch Hopwood 1946 31606 Aerofilms Alvechurch 1947 27772 Aerofilms Alvechurch 1956 11692 Aeropictorial Alvechurch 1974 56680 - 56687 Aerofilms W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Ashton-Under-Hill Crop Marks 1959 21190 - 21191 Extra - Mural Dept. Astley Crop Marks 1956 21252 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. Astley Crop Marks 1956 - 1957 21251 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. Astley Roman Fort 1957 21210 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. Aston Somerville 1974 56688 Aerofilms Badsey 1955 7689 Dr. J.K.S. St. Joseph, Cambridge University Badsey 1967 40338 Aerofilms Badsey 1967 40352 - 40357 Aerofilms Badsey 1968 40944 Aerofilms Badsey 1974 56691 - 56694 Aerofilms Beckford Crop Marks 1959 21192 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. -

A Superb Village House

A superb village house Little Manor, Blockley, Gloucestershire GL56 9DW Freehold Entrance hall • Sitting room • Dining room • Study • Snug • Kitchen • Utility room • Cloakroom • Three bedrooms • Three bathrooms • Garage • Parking • Gardens Mileages Chipping Campden 3.5 miles. Moreton-in-Marsh 3.5 miles (mainline trains to London/ Paddington from 90 minutes). Stratford-upon-Avon 18.5 miles. Oxford 30 miles. Birmingham International Airport 40 miles (all times and distances are approximate). Situation and Communications Blockley is situated within the Cotswold Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty between Chipping Campden and Moreton-in-Marsh. The village provides a Post Office, village store, two hotels, public house, a medieval church, school and sports club. Moreton-in-Marsh has a mainline rail station serving London Paddington. Cirencester, Stratford-upon- Avon and Cheltenham are all within reasonable distance. The property lies within the catchment area for Chipping Campden school. Excellent riding and walking within countryside designated as a special landscape area. There are many historic houses and gardens in the immediate locality. Little Manor A lawned area with well Dating back to the stocked borders and mature seventeenth-century with later hedges lies to the front of the additions, Little Manor is property. situated in the popular village The property is approached of Blockley. The property is through double gates which Grade II Listed and offers lead to the garage and ample stylishly presented traditional parking. accommodation over three floors. The property was the subject of an extensive programme of refurbishment and rebuilding in 2006/2007. The property is wired for WiFi throughout. Elegant triple aspect sitting room with fireplace and French doors out to the garden. -

Records Indexes Tithe Apportionment and Plans Handlist

Records Service Records Indexes Tithe Apportionment and Plans handlist The Tithe Commutation Act of 1836 replaced the ancient system of payment of tithes in kind with monetary payments. As part of the valuation process which was undertaken by the Tithe Commissioners a series of surveys were carried out, part of the results of which are the Tithe Maps and Apportionments. An Apportionment is the principal record of the commutation of tithes in a parish or area. Strictly speaking the apportionment and map together constitute a single document, but have been separated to facilitate use and storage. The standard form of an Apportionment contains columns for the name(s) of the landowners and occupier(s); the numbers, acreage, name or description, and state of cultivation of each tithe area; the amount of rent charge payable, and the name(s) of the tithe-owner(s). Tithe maps vary greatly in scale, accuracy and size. The initial intent was to produce maps of the highest possible quality, but the expense (incurred by the landowners) led to the provision that the accuracy of the maps would be testified to by the seal of the commissioners, and only maps of suitable quality would be so sealed. In the end, about one sixth of the maps had seals. A map was produced for each "tithe district", that is, one region in which tithes were paid as a unit. These were often distinct from parishes or townships. Areas in which tithes had already been commutated were not mapped, so that coverage varied widely from county to county. -

Notice of Poll Bromsgrove 2021

NOTICE OF POLL Bromsgrove District Council Election of a County Councillor for Alvechurch Electoral Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Alvechurch Electoral Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 07:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BAILES 397 Birmingham Road, Independent Kilbride Karen M(+) Van Der Plank Alan Bordesley, Redditch, Kathryn(++) Worcestershire, B97 6RH LUCKMAN 40 Mearse Lane, Barnt The Conservative Party Woolridge Henry W(+) Bromage Daniel P(++) Aled Rhys Green, B45 8HL Candidate NICHOLLS 3 Waseley Road, Labour Party Hemingway Oreilly Brett A(++) Simon John Rubery, B45 9TH John L F(+) WHITE (Address in Green Party Ball John R(+) Morgan Kerry A(++) Kevin Bromsgrove) 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote thereat Rowney Green Peace Mem. Hall, Rowney Green Lane, Rowney 1 ALA-1 to ALA-752 Green Beoley Village Hall, Holt End, Beoley 2 ALB-1 to ALB-809 Alvechurch Baptist Church, Red Lion Street, Alvechurch 3 ALC-1 to ALC-756 Alvechurch -

Catalogue of Adoption Items Within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window

Catalogue of Adoption Items within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window The cloister Windows were created between 1916 and 1999 with various artists producing these wonderful pictures. The decision was made to commission a contemplated series of historical Windows, acting both as a history of the English Church and as personal memorials. By adopting your favourite character, event or landscape as shown in the stained glass, you are helping support Worcester Cathedral in keeping its fabric conserved and open for all to see. A £25 example Examples of the types of small decorative panel, there are 13 within each Window. A £50 example Lindisfarne The Armada A £100 example A £200 example St Wulfstan William Caxton Chaucer William Shakespeare Full Catalogue of Cloister Windows Name Location Price Code 13 small decorative pieces East Walk Window 1 £25 CW1 Angel violinist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW2 Angel organist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW3 Angel harpist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW4 Angel singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW5 Benedictine monk writing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW6 Benedictine monk preaching East Walk Window 1 £50 CW7 Benedictine monk singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW8 Benedictine monk East Walk Window 1 £50 CW9 stonemason Angel carrying dates 680-743- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW10 983 Angel carrying dates 1089- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW11 1218 Christ and the Blessed Virgin, East Walk Window 1 £100 CW12 to whom this Cathedral is dedicated St Peter, to whom the first East Walk Window 1 £100 CW13 Cathedral was dedicated St Oswald, bishop 961-992, -

Site Name Address Holiday Static Residential Tourer Badgers Walk Park Home Estate Bayton Common, Clows Top, Kiddeminster, DY14 9NT 2 17

Site Name Address Holiday static Residential Tourer Badgers Walk Park Home Estate Bayton Common, Clows Top, Kiddeminster, DY14 9NT 2 17 Blakehouse Farm Eastham, Tenbury Wells WR15 8NS 42 (Feb - Nov) Boye Meadow Severn Bridge, Upton upon Severn 32 (Mar - Oct) Brant House Farm Shrawley 31 8 Broad Oaks Lodge Hanley Swan, WR8 0AT 1 Broombank Caravan Park Broombank, Lindridge, Tenbury Wells 1 Broomfield (formerly Broom Inn) Caravan Site licence - Broom Inn Caravan site Lindridge Tenbury Wells WR15 8NX 4 Caldicotts Caravan Park Shrawley 76 Caraburn Caravan Site, Gumburn Farm, Sinton Green 10 Caravan 1 & 2, Hope House Farm Hope House Lane, Martley, WR6 6QF 2 Coppice Caravan Park Ockeridge Wood, Wichenford 162 1 14 Dragons Orchard Leigh Sinton, worcs, WR13 5DS 1 2 Duke of York Caravan Site Berrow, Malvern, WR13 6AS 4 22 Farmers Arms Bestmans Lane, Kempsey, WR5 3QA 6 1 Hillside Broadwas 3 Hook Bank Barr Park, Hook Bank, Henley Castle, WR8 0AY 37 Larford Lake Larford Lane, Larford, Nr Astley Cross, Stourport-on-severn, DY13 OSQ 7 (12 mths) 0 Lenchford Meadow Shrawley WR6 6TB 60 2 12 Lower Farm Caravan The Lodge, Callow Road, MartleyWR6 6QN 1 Marlbrook Farm Castle Morton, Malvern, WR13 6LE 5 (day before Good Fri - Oct) Norgroves End Caravan Park Bayton, Kidderminster, DY14 9LX 99 (Mar - Jan) Knighton on Teme Caravan Park Knighton on Teme WR15 8NA 90 (Mar - Oct) Oakmere Caravan Site Hanley Swan, WR8 ODZ 135 21 Ockeridge Rural Retreats Ockeridge Wichenford Worcester WR6 6YR 4 Orchard opposite school Holt Heath 5 0 Orchard Caravan Park St Michaels, -

Alvechurch Parish Design Statement

ALVECHURCH PARISH DESIGN STATEMENT A Community Voice for Rural Character Forms part of the Alvechurch Parish Neighbourhood Plan MARCH 2018 Alvechurch Parish Design Statement 2017 http://www.alvechurch.gov.uk/ HOW TO USE THIS DESIGN STATEMENT 5 THE PEOPLE WHO CREATED THE DESIGN STATEMENT 8 SECTION 1 FEATURES COMMON THROUGHOUT THE PARISH 9 SECTION 1.1 HISTORY 9 SECTION 1.2 LANDSCAPE SETTING AND WILDLIFE 10 SECTION 1.3 SETTLEMENT FORM 11 SECTION 1.4 BUILDINGS 13 SECTION 1.5 HIGHWAYS AND RELATED FEATURES 14 SECTION 2: FEATURES OF ALVECHURCH VILLAGE 15 SECTION 2.1 HISTORY: 15 SECTION 2.2.LANDSCAPE SETTING AND WILDLIFE 15 SECTION 2.3 SETTLEMENT FORM: 16 SECTION 2.4. BUILDINGS ; 18 SECTION 2.5 HIGHWAYS AND RELATED FEATURES 20 SECTION 3 FEATURES OF WITHYBED GREEN 22 SECTION 3.1 HISTORY; 22 SECTION 3.2 LANDSCAPE SETTING AND WILDLIFE: 22 SECTION 3.3 SETTLEMENT FORM 22 SECTION 3.4 BUILDINGS; 23 SECTION 3.4 HIGHWAYS AND RELATED FEATURES 23 SECTION 4: FEATURES OF ROWNEY GREEN 24 REFER ALSO TO FEATURES COMMON THROUGHOUT PARISH-P10-12 24 SECTION 4.1 HISTORY: 24 SECTION 4.2 LANDSCAPE SETTING AND WILDLIFE 24 SECTION 4.3 SETTLEMENT FORM, REFER ALSO TO FEATURES COMMON THROUGHOUT PARISH – P9-11 25 SECTION 4.4 BUILDINGS: 26 SECTION 4.5 HIGHWAYS AND RELATED FEATURES 27 SECTION 5: FEATURES OF HOPWOOD 28 SECTION 5.1 HISTORY; 28 SECTION 5.2 LANDSCAPE SETTING AND WILDLIFE: 28 SECTION 5.3 SETTLEMENT FORM:, 28 SECTION 5.4 BUILDINGS 30 SECTION 5.5 HIGHWAYS AND RELATED FEATURES 30 FEATURES OF HOPWOOD 31 SECTION 6 FEATURES OF BORDESLEY 32 SECTION 6.1 HISTORY 32 SECTION -

ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Her Mon Mæg Giet Gesion Hiora Swæð

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Her mon mæg giet gesion hiora swæð EXECUTIVE EDITORS Simon Keynes, Rosalind Love and Andy Orchard Editorial Assistant Dr Brittany Schorn ([email protected]) ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD Professor Robert Bjork, Arizona State University, Tempe AZ 85287-4402, USA Professor John Blair, The Queen’s College, Oxford OX1 4AW, UK Professor Mary Clayton, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland Dr Richard Dance, St Catharine’s College, Cambridge CB2 1RL, UK Professor Roberta Frank, Dept of English, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA Professor Richard Gameson, Dept of History, Durham University, Durham DH1 3EX, UK Professor Helmut Gneuss, Universität München, Germany Professor Simon Keynes, Trinity College, Cambridge CB2 1TQ, UK Professor Michael Lapidge, Clare College, Cambridge CB2 1TL, UK Professor Patrizia Lendinara, Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione, Palermo, Italy Dr Rosalind Love, Robinson College, Cambridge CB3 9AN, UK Dr Rory Naismith, Clare College, Cambridge CB2 1TL, UK Professor Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, University of California, Berkeley, USA Professor Andrew Orchard, Pembroke College, Oxford OX1 1DW, UK Professor Paul G. Remley, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-4330, USA Professor Paul E. Szarmach, Medieval Academy of America, Cambridge MA 02138, USA PRODUCTION TEAM AT THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Sarah Westlake (Production Editor, Journals) <[email protected]> Daniel Pearce (Commissioning Editor) <[email protected]> Cambridge University Press, Edinburgh Building, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge CB2 8BS Clare Orchard (copyeditor) < [email protected]> Dr Debby Banham (proofreader) <[email protected]> CONTACTING MEMBERS OF THE EDITORIAL BOARD If in need of guidance whilst preparing a contribution, prospective contributors may wish to make contact with an editor whose area of interest and expertise is close to their own.