UNCORRECTED PROOF 136 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUNTA ARENAS CAMPANA CAUTIN Colegio 0950 LONGAVI 700 600 CARAHUE 0700 VALDIVIA 8647 SANTA RAQUEL

CANCILLER BRANDT CHAÑARCILLO G. ACOSTA PJE. EL TENIENTE POTRERILLOS FAMASOL SANTA ELENA Pasarela Peatonal 7750 EL BLANCO G. ACOSTA LOTA EL TOFO 300 7600 Sede Social ANDINA PJE 12 COLIPIT. PEREZ Restaurant Capilla R. TORO SAN JAIME 300 Villa GERONIMO DE ALDERETE 01200 PEÑUELAS Junta de NIEBLA DICHATO PJE. E03 Vecinos SURVEYOR Colegio LINARES GEMINIS Jardín 850 0700 GERONIMOInfantil DE ALDERETE 500 DON PEPE 300 1290 PJE PAIPOTE 7800 LUNIK HANGA-ROA MARINERS 1200 SPUTNIK RANQUIL Multicanchas LA SERENA Sede Social Pasarela AVDA. CORONEL 7900 Peatonal SOYUZ COSMOS Colegio MARINERS CORCOVADO 0800 Iglesia 400 1200 500 GRUMETE CORTÉS TELSTAR APOLO XI 850 Cancha PICHINMAVIDA 8000 0500 GERONIMO DE ALDERETE GRUMETE HERNANDEZ GRUMETE MACHADO GRUMETE VOLADOS Capilla G. BRICEÑO G. ESPINO 1200 G. VARGAS Capilla 0990 STA. JULIA VOSTOK 8000 Paso Club 850 Bajo GRUMETE SEPULVEDA Deportivo 0900 Multicanchas PIUQUENES PANGUIPULLI Nivel 7900 7900 0850 8000 7900 TELSTAR 7900 Cancha Junta de 0810 PJE 3 850 Vecinos 0700 7900 CRUCES 7900 Cancha GRUMETE PEREIRA G. QUINTEROS Capilla 7900 Hogar de Niños G. MIRANDA COMBARBALA ACONCAGUA y Ancianos G. PÉREZ 7900 DARWIN E10 MONTE 850 STOKES 100 8200 8200 PUERTO VARAS PJE LA PARVA CHOSHUENCO 8100 VILLARRICA CAÑETE INCA DE ORO SANTA RAQUEL AVDA. CORONEL 100 P. EL PEUMO P. EL QUILLAY LOS ALERCES PJE LA HIGUERILLA 01000 AV. AMERICO VESPUCIOOJOS DEL SALADO P. LA LUMA CALLE D LIRQUEN 8100 CALBUCO TRONADOR 100 ACONCAGUA 500 PJE EL PEUMO LOS CONDORES Iglesia ARICA EL QUILLAY COLBÚN SAUSALITO CALAFQUEN EL LINGUE Iglesia 0990 PASAJE 41 EL LITRANCURA TAMARUGO PJE TUCÁN 0905 PJE EL PEUMO 8000 PasarelaPasarela E10 LEONORA LATORRE CACHAPOAL PeatonalPeatonal 0800 TOME 8000 8300 8000 8000 PJE ALONDRA 0700 PELLÍN 8377 8377 8377 8377 9 ORIENTE LIMARI 8000 TOME 8 ORIENTE 0964 7 ORIENTE 5 NORTE 6 ORIENTE 8000 4 ORIENTE 5 ORIENTE LAUTARO 10 ORIENTE MIÑO Comercio 0700 0750 C. -

Flora of the Mediterranean Basin in the Chilean Espinales: Evidence of Colonisation

PASTOS 2012. ISSN: 0210-1270 PASTOS, 42 (2), 137 - 160 137 FLORA OF THE MEDITERRANEAN BASIN IN THE CHILEAN ESPINALES: EVIDENCE OF COLONISATION I. MARTÍN-FORÉS1, M. A. CASADO1*, I. CASTRO2, C. OVALLE3, A. DEL POZO4, B. ACOSTA-GALLO1, L. SÁNCHEZ-JARDÓN1 AND J. M. DE MIGUEL1 1Departamento de Ecología. Facultad de Biología. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid (España). 2Departamento de Ecología. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Madrid (España). 3Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias INIA-La Cruz. La Cruz (Chile). 4Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad de Talca. Talca (Chile). *Author for correspondence: M.A. Casado ([email protected]). SUMMARY In Chile’s Mediterranean region, over 18% of plant species are alien. This is particularly noteworthy in some agrosilvopastoral systems such as the espinales, which are functionally very similar to the Spanish dehesas and are of great ecological and socioeconomic interest. In the present paper we analyse Chile’s non-native flora, considering three scales of analysis: national, regional (the central region, presenting a Mediterranean climate) and at community level (the espinales within the central region). We compare this flora with that recorded in areas of the Iberian Peninsula with similar lithological and geomorphological characteristics, and land use. We discuss possible mechanisms that might have been operating in the floristic colonisation from the Mediterranean Basin to Chile’s Mediterranean region. Key words: Alien plants, biogeography, Chile, life cycle, Spain. INTRODUCTION Historically, the transit of goods, domestic animals and people has favoured the flow of wild organisms around the planet (Lodge et al., 2006), a fact that is often associated with the introduction of cultural systems, which have contributed to generating new environmental and socioeconomic scenarios (Le Houérou, 1981; Hobbs, 1998; Grenon and Batisse, 1989). -

Holocene Relative Sea-Level Change Along the Tectonically Active Chilean Coast

This is a repository copy of Holocene relative sea-level change along the tectonically active Chilean coast. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/161478/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Garrett, Ed, Melnick, Daniel, Dura, Tina et al. (5 more authors) (2020) Holocene relative sea-level change along the tectonically active Chilean coast. Quaternary Science Reviews. 106281. ISSN 0277-3791 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106281 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Holocene relative sea-level change along the tectonically active Chilean coast 2 3 Ed Garrett1*, Daniel Melnick2, Tina Dura3, Marco Cisternas4, Lisa L. Ely5, Robert L. Wesson6, Julius 4 Jara-Muñoz7 and Pippa L. Whitehouse8 5 6 1 Department of Environment and Geography, University of York, York, UK 7 2 Instituto de Ciencias de la Tierra, TAQUACh, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile 8 3 Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA 9 4 Instituto de Geografía, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile 10 5 Department of Geological Sciences, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA, USA 11 6 U.S. -

Effects of Dry-Season N Input on the Productivity and N Storage of Mediterranean-Type Shrublands

Ecosystems (2009) 12: 473–488 DOI: 10.1007/s10021-009-9236-6 � 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC Effects of Dry-Season N Input on the Productivity and N Storage of Mediterranean-Type Shrublands George L. Vourlitis,1* Sarah C. Pasquini,1,2 and Robert Mustard1 1Department of Biological Sciences, California State University, San Marcos, California 92096, USA; 2Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA ABSTRACT Anthropogenic nitrogen (N) deposition is a globally leaching in chaparral but not CSS. Nitrogen addi important source of N that is expected to increase tion also lead to an increase in litter and tissue N with population growth. In southern California, N concentration and a decline in the C:N ratio, but input from dry deposition accumulates on vegeta failed to alter the ecosystem productivity and N tion and soil surfaces of chaparral and coastal sage storage of the chaparral and CSS shrublands over scrub (CSS) ecosystems during the summer and fall the 4-year study period. The reasons for the lack of and becomes available as a pulse following winter a treatment response are unknown; however, it is rainfall. Presumably, N input will act to stimulate possible that these semi-arid shrublands are not N the productivity and N storage of these Mediterra limited, cannot respond rapidly enough to capture nean-type, semi-arid shrublands because these the ephemeral N pulse, are limited by other nutri ecosystems are thought to be N limited. To assess ents, or the N response is dependent on the amount whether dry-season N inputs alter ecosystem pro and/or distribution of rainfall. -

Neotectonics Along the Eastern Flank of the North Patagonian Icefield, Southern Chile: Cachet and Exploradores Fault Zones

XII Congreso Geológico Chileno Santiago, 22-26 Noviembre, 2009 S9_053 Neotectonics along the eastern flank of the North Patagonian Icefield, southern Chile: Cachet and Exploradores fault zones Melnick, D.1, Georgieva, V.1, Lagabrielle, Y.2, Jara, J.3, Scalabrino, B.2, Leidich, J.4 (1) Institute of Geosciences, University of Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam, Germany. (2) UMR 5243 Géosciences Montpellier, Université de Montpellier 2, France. (3) Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra, Universidad de Concepción, Chile. (4) Patagonia Adventure Expeditions, Casilla 8, Cochrane, Chile. [email protected] Introduction In the southern Andes, the North Patagonian Icefield (NPI) is a poorly-known region in terms of geology and neotectonics that marks a major topographic anomaly at the transition between the Austral and Patagonian Andes. The NPI is located immediately east of the Nazca-Antarctic-South America Triple Plate Junction, where the Chile Rise collides against the margin (Fig. 1A). Since 14 Ma, this Triple Junction has migrated northward as a result of oblique plate convergence, resulting in collision and subduction of two relatively short ridge segments in the Golfo de Penas region at 6 and 3 Ma, and at present of one segment immediately north of the Taitao Peninsula [1]. Oblique plate convergence in addition to collision of these ridge segments resulted in the formation of a forearc sliver, the Chiloe block, which is decoupled from the South American foreland by the Liquiñe-Ofqui fault zone. Here we present geomorphic and structural field evidence that indicates neotectonic activity in the internal part of the orogen, along the flanks of the NPI (Fig. -

Actas III Seminario Un Encuentro Con Nuestra Historia 1

Actas III Seminario Un Encuentro con Nuestra Historia 1 ACTAS III SEMINARIO UN ENCUENTRO CON NUESTRA HISTORIA SOCIEDAD DE HISTORIA Y GEOGRAFÍA DE AISÉN COYHAIQUE CHILE Sociedad de Historia y Geografía de Aisén 2 Actas III Seminario Un Encuentro con Nuestra Historia. © Sociedad de Historia y Geografía de Aisén Registro de Propiedad Intelectual Nº 173.977 ISBN Nº 978-956-8647-02-5 Representante legal: Mauricio Osorio Pefaur Producción, compilación y correcciones: Leonel Galindo Oyarzo & Mauricio Osorio Pefaur Corrección de estilo y diagramación final: Ediciones Ñire Negro, [email protected] Diseño de portada: Paulina Lobos Echaveguren, [email protected] Fotografías portada: don Baldo Araya Uribe en dos épocas de su vida. En 1950 y con 26 años, trabajaba en el Consulado chileno en Bariloche y en la radio L.U.8 de dicha ciudad. En 2001, a los 77 años, viviendo en Coyhaique. Gentileza de su hija, Inés Araya Echaveguren. Fotografía contraportada: Paisaje sector Escuela Vieja Cerro Castillo. Archivo Mauricio Osorio P. Fotografías interiores: págs 29, 59, 88, 95 y 103 aportadas por los autores. Págs 22, 40 y 56 aportadas por editor. Fono : (56) (67) 246151 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Impresión: Lom Ediciones, Santiago de Chile Tiraje: 500 ejemplares Edición financiada con el aporte del Gobierno Regional de Aisén Coyhaique, 2008 Actas III Seminario Un Encuentro con Nuestra Historia 3 ÍNDICE CONTENIDOS PÁGINA DON BALDO ARAYA URIBE 5 PRESENTACIÓN 7 PONENCIAS: ARCHIVOS: EL PAPEL DE LA MEMORIA. LA EXISTENCIA ESTABLECIDA 9 Carmen Gloria Parés Fuentes UTTI POSIDETTIS ‘LO QUE POSEÉIS’. LA LARGA CONTROVERSIA DE LÍMITES DE CHILE Y ARGENTINA 15 Danka Ivanoff Wellmann LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL PASO SAN CARLOS FRENTE AL SALTÓN DEL RÍO BAKER: APORTES PARA EL RECONOCIMIENTO DEL TRABAJO DE LAS COMISIONES DE LÍMITES CHILENAS EN LA PATAGONIA OCCIDENTAL, INICIOS DEL S. -

Alloway Etal 2018 QSR.Pdf

Quaternary Science Reviews 189 (2018) 57e75 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Mid-latitude trans-Pacific reconstructions and comparisons of coupled glacial/interglacial climate cycles based on soil stratigraphy of cover-beds * B.V. Alloway a, b, , P.C. Almond c, P.I. Moreno d, E. Sagredo e, M.R. Kaplan f, P.W. Kubik g, P.J. Tonkin h a School of Environment, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand b Centre for Archaeological Science (CAS), School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, 2522, Australia c Department of Soil and Physical Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, PO Box 8084, Lincoln University, Canterbury, New Zealand d Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad, Departamento de Ciencias Ecologicas, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 653, Santiago, Chile e Instituto de Geografía, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Av. Vicuna Mackenna, 4860, Santiago, Chile f Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Columbia University, Palisades, NY, 10964-8000, United States g Paul Scherrer Institut, c/o Institute of Particle Physics, HPK H30, ETH Hoenggerberg, CH-8093, Zurich, Switzerland h 16 Rydal Street, Christchurch 8025, New Zealand article info abstract Article history: South Westland, New Zealand, and southern Chile, are two narrow continental corridors effectively Received 19 December 2017 confined between the Pacific Ocean in the west and high mountain ranges in the east which impart Received in revised form significant influence over regional climate, vegetation and soils. In both these southern mid-latitude 6 April 2018 regions, evidence for extensive and repeated glaciations during cold phases of the Quaternary is man- Accepted 6 April 2018 ifested by arrays of successively older glacial drift deposits with corresponding outwash plain remnants. -

Notes on Variation and Geography in Rayjacksonia Phyllocephala (Asteraceae: Astereae)

Nesom, G.L., D.J. Rosen, and S.K. Lawrence. 2013. Notes on variation and geography in Rayjacksonia phyllocephala (Asteraceae: Astereae). Phytoneuron 2013-53: 1–15. Published 12 August 2013. ISSN 2153 733X NOTES ON VARIATION AND GEOGRAPHY IN RAYJACKSONIA PHYLLOCEPHALA (ASTERACEAE: ASTEREAE) GUY L. NESOM 2925 Hartwood Drive Fort Worth, Texas 76109 [email protected] DAVID J. ROSEN Department of Biology Lee College Baytown, Texas 77522-0818 [email protected] SHIRON K. LAWRENCE Department of Biology Lee College Baytown, Texas 77522-0818 ABSTRACT Inflorescences of Rayjacksonia phyllocephala in the disjunct Florida population system are characterized by heads on peduncles with leaves mostly reduced to linear bracts; heads in inflorescences of the Mexico-Texas-Louisiana system are immediately subtended by relatively unreduced leaves. The difference is consistent and justifies recognition of the Florida system as R. phyllocephala var. megacephala (Nash) D.B. Ward. Scattered waifs between the two systems are identified here as one or the other variety, directly implying their area of origin. In the eastern range of var. phyllocephala , at least from Brazoria County, Texas, eastward about 300 miles to central Louisiana, leaf margins vary from entire to deeply toothed-spinulose. In contrast, margins are invariably toothed-spinulose in var. megacephala as well as in the rest of southeastern Texas (from Brazoria County southwest) into Tamaulipas, Mexico. In some of the populations with variable leaf margins, 70-95% of the individuals have entire to mostly entire margins. KEY WORDS : Rayjacksonia , morphological variation, leaf margins, disjunction, waifs Rayjacksonia phyllocephala (DC.) Hartman & Lane (Gulf Coast camphor-daisy) is an abundant and conspicuous species of the shore vegetation around the Gulf of Mexico. -

Round the Llanquihue Lake

Round the Llanquihue Lake A full day spent exploring the corners of this magnificent lake. The third biggest of South America, and the second of Chile with 330sq miles. It is situated in the southern Los Lagos Region in the Llanquihue and Osorno provinces. The lake's fan-like form was created by successive piedmont glaciers during the Quaternary glaciations. The last glacial period is called Llanquihue glaciation in Chile after the terminal moraine systems around the lake. We will enjoy unique views from the Volcano Osorno introducing us to the peaceful rhythm of a laid back life. Meet your driver and guide at your hotel. Bordering the south lake Llanquihue acrros the Vicente Perez Rosales National Park visiting the resort of Ensenada and the Petrohue River Falls. The tour will continue up to the Osorno Volcano, Ski Resort, 1200 mts asl. (3937 feet asl.) where you will get spectacular views of the Mt Tronador, Volcano Puntiagudo,Llanquihue lake, and if is clear enough even the Reloncavi sound and of course the whole valley of Petrohue river. For the itchy feet we can go for a short walk to the crater rojo and back. (1hr) Or optional chair lift instead. You can bring your own lunch box and have it here or get something at the restaurant. Continuation to the northern border of Llanquihue Lake driving across some of the least visited sides of the lake where agriculture and cattle ranches take part of the local economy passing through Cascadas village. We will reach the picturesque village of Puerto Octay, located on a quiet bay enclosed by the Centinela Peninsula and then to the city of Frutillar, with its houses built in German style with lovely gardens represent the arquitecture in the mid 30/s when the first settlers arrived to begin a hard working life in the south. -

Huertas Familiares Y Comunitarias: Cultivando Soberanía Alimentaria

Huertas familiares y comunitarias: cultivando soberanía alimentaria José Tomás Ibarra, Julián Caviedes, Antonia Barreau y Natalia Pessa editores Huertas familiares y comunitarias: cultivando soberanía alimentaria EDICIONES UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE CHILE Vicerrectoría de Comunicaciones Av. Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins 390, Santiago, Chile [email protected] www.ediciones.uc.cl FUNDACIÓN PARA LA INNOVACIÓN AGRARIA (FIA) HUERTAS FAMILIARES Y COMUNITARIAS: CULTIVANDO SOBERANÍA ALIMENTARIA José Tomás Ibarra, Julián Caviedes, Antonia Barreau y Natalia Pessa Registro de Propiedad Intelectual © Inscripción Nº 295.379 Derechos reservados Enero 2019, Villarrica, Chile. ISBN N° 978-956-14-2331-2 Ilustraciones: Belén Chávez Diseño: Leyla Musleh Impresor: Aimpresores CIP-Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Huertas familiares y comunitarias: cultivando soberanía alimentaria / José Tomás Ibarra [y otros], editores. Incluye bibliografías. 1. Huertos 2. Explotación agrícola familiar I. Ibarra Eliessetch, José Tomás, editor. 2018 635 + dc 23 RDA Cómo citar este libro: Ibarra, J. T., J. Caviedes, A. Barreau & N. Pessa (Eds). 2019. Huertas familiares y comunitarias: cultivando soberanía alimentaria. Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile. 228 pp. La presente publicación reúne una serie de experiencias relacionadas a la agricultura familiar y a huertas familiares y comunitarias en Chile. Este trabajo se desarrolló en el marco del proyecto “Huerta andina de La Araucanía como patrimonio biocultural: un enfoque agroecológico y agroturístico” -

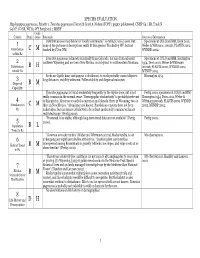

1 C M 2 B H 3 B M 4 C M 5 B L 6 B M 7 B M 8

SPECIES EVALUATION Haplopappus pygmaeus, Priority 1. Tonestus pygmaeus (Torrey & Gray) A. Nelson (TOPY). pygmy goldenweed. CNHP G4 / SR, Track N G4 N?. CO SR, WY S1. WY Peripheral 2 MBNF Confi- Criteria Rank dence Rationale Sources of Information Distribution (see map below) is “nearly continuous,” so rating C was chosen, but Specimens at COLO and RM, Dorn 2001, 1 none of the pictures or descriptions really fit this species. Tracked by WY, but not Weber & Wittmann 2001ab, PLANTS 2002, Distribution C M tracked by CO or NM. WYNDD 2002. within R2 Tonestus pygmaeus is known principally from Colorado, but also from adjacent Specimens at COLO and RM, Harrington 2 southern Wyoming and northern New Mexico, and disjunct in southwestern Montana. 1954, Dorn 2001, Weber & Wittmann Distribution B H 2001ab, PLANTS 2002, WYNDD 2002, outside R2 MTNHP 2002. Seeds are lightly hairy and pappus is deciduous, so seeds probably cannot disperse Harrington 1954. 3 long distances; viability unknown. Pollen viability and dispersal unknown. Dispersal B M Capability Tonestus pygmaeus is found moderately frequently in the Alpine zone, but is not Fertig 2000, specimens at COLO and RM, really common in the normal sense. “Demographic stochasticity” is probably irrelevant Harrington 1954, Dorn 2001, Weber & 4 to this species. About 50 recorded occurrences in Colorado, three in Wyoming, two or Wittmann 2001ab, PLANTS 2002, WYNDD Abundance in C M three in New Mexico. “Abundance not known. Population censuses have not been 2002, MTNHP 2002. R2 undertaken, but the species is believed to be at least moderately common within its restricted range” (Fertig 2000). -

4 Three-Dimensional Density Model of the Nazca Plate and the Andean Continental Margin

76 4 Three-dimensional density model of the Nazca plate and the Andean continental margin Authors: Andrés Tassara, Hans-Jürgen Götze, Sabine Schmidt and Ron Hackney Paper under review (September 27th, 2005) by the Journal of Geophysical Research Abstract We forward modelled the Bouguer anomaly in a region encompassing the Pacific ocean (east of 85°W) and the Andean margin (west of 60°W) between northern Peru (5°S) and Patagonia (45°S). The three-dimensional density structure used to accurately reproduce the gravity field is simple. The oceanic Nazca plate is formed by one crustal body and one mantle lithosphere body overlying a sub-lithospheric mantle, but fracture zones divide the plate into seven along-strike segments. The subducted slab was modelled to a depth of 410 km, has the same structure as the oceanic plate, but it is subdivided into four segments with depth. The continental margin consists of one upper-crustal and one lower-crustal body without lateral subdivision, whereas the mantle has two bodies for the lithosphere and two bodies for the asthenosphere that are separated across-strike by the downward prolongation of the eastern limit of active volcanism. We predefined the density for each body after studying its dependency on composition of crustal and mantle materials and pressure-temperature conditions appropriate for the Andean setting. A database containing independent geophysical information constrains the geometry of the subducted slab, locally the Moho of the oceanic and continental crusts, and indirectly the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (LAB) underneath the continental plate. Other geometries, especially that of the intracrustal density discontinuity (ICD) in the continental margin, were not constrained and are the result of fitting the observed and calculated Bouguer anomaly during the forward modelling.