MTO 19.1: Hesselink, Radiohead's “Pyramid Song”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiohead's Pre-Release Strategy for in Rainbows

Making Money by Giving It for Free: Radiohead’s Pre-Release Strategy for In Rainbows Faculty Research Working Paper Series Marc Bourreau Telecom ParisTech and CREST Pinar Dogan Harvard Kennedy School Sounman Hong Yonsei University July 2014 RWP14-032 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at: http://web.hks.harvard.edu/publications The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Makingmoneybygivingitforfree: Radiohead’s pre-release strategy for In Rainbows∗ Marc Bourreau†,Pınar Dogan˘ ‡, and Sounman Hong§ June 2014 Abstract In 2007 a prominent British alternative-rock band, Radiohead, pre-released its album In Rainbows online, and asked their fans to "pick-their-own-price" (PYOP) for the digital down- load. The offer was available for three months, after which the band released and commercialized the album, both digitally and in CD. In this paper, we use weekly music sales data in the US between 2004-2012 to examine the effect of Radiohead’s unorthodox strategy on the band’s al- bum sales. We find that Radiohead’s PYOP offer had no effect on the subsequent CD sales. Interestingly, it yielded higher digital album sales compared to a traditional release. -

Critics' Picks for Best Books and Movies of the Year

Critics' Picks for Best Books and Movies of the Year VOA Special English (voaspecialenglish.com) is Voice of America's daily news and information service for English learners. Read the story and then do the activities at the end. AP From left, Brad Pitt, Jessica Chastain and Sean Penn arrive for "The Tree of Life" at the Cannes film festival in France DOUG JOHNSON: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. I'm Doug Johnson. Today on our show: the best books and movies from two thousand eleven. Plus, we play some of the music we missed this year. Best Books DOUG JOHNSON: Hundreds of great books are published in America every year. And every year, editors, critics and other readers try to choose a list of favorites. The many lists for twenty-eleven cover almost every kind of fiction you can imagine. A few books showed up on list after list of the best fiction from this year. One of them was Ann Patchett's "State of Wonder." Publishers Weekly described the novel as one "readers will hate to see end." The story centers on a drug researcher from Minnesota named Maria Singh. She travels to Brazil to investigate the death of a co-worker. Her search takes her deep into the Amazon area and danger. But, she also goes deep into her own soul for a close look at who she is, what she has lost in her life and how she wants the future to look. Special English is part of VOA Learning English: voanews.com/learningenglish | January 2012 | 1 Ann Patchett lives in Tennesee. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

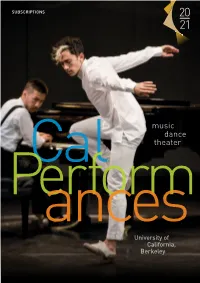

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

Radiohead Paranoid Android Reaction

Radiohead paranoid android reaction Continue 1997 studio album RadioheadOK ComputerStudio album RadioheadReleased21 May 1997 (1997-05-21)Recorded4 September 1995 (Lucky) July 1996 - March 1997StudioCanned Applause Didcot, EnglandSt Catherine Court, Bath, EnglandGenreAlternative rockart rockprogressive rockLength53:21LabelParlophoneCapitolProducerNigel GodrichRadiohead chronology The Bends (1995) OK Computer (1995) OK Computer (1995)1997) No Surprises/Running from Demons (1997) Radiohead Studio Album Timeline The Bends (1995) OK Computer (1997) Kid A (2997) 000) Singles with OK Computer Paranoid Android Released: May 26, 1997 Karma Police Released: August 25, 1997 Lucky Released: December 1997 No Surprises Released: 12 January 1998 OK Computer is the third studio album by English rock band Radiohead, released on May 21, 1997 on the subsidiaries of EMIlo Parphone Records and Capitol Records. Radiohead members independently released the album with Nigel Godrich, an arrangement they used for their subsequent albums. In addition to the song Lucky, recorded in 1995, Radiohead recorded OK Computer in Oxfordshire and Bath between 1996 and early 1997, mainly in the historic St Catherine's Court mansion. The band distanced themselves from the guitar, lyrically introspective style of their previous album The Bends. THE abstract texts of OK Computer, densely layered sound and eclectic influences laid the groundwork for Radiohead's later, more experimental works. The album depicts a world fraught with unbridled consumerism, social exclusion, emotional isolation and political malaise; as such, OK Computer is said to have a prophetic understanding of the mood of 21st century life. Unconventional production methods on the album include natural reverb through recording on the stairs, and the lack of audio separation, allowing the instruments not to reconnect separately. -

6. the Evolving Role of Music Journalism Zachary Woolfe and Alex Ross

Classical Music Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges Classical Music This kaleidoscopic collection reflects on the multifaceted world of classical music as it advances through the twenty-first century. With insights drawn from Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges leading composers, performers, academics, journalists, and arts administrators, special focus is placed on classical music’s defining traditions, challenges and contemporary scope. Innovative in structure and approach, the volume comprises two parts. The first provides detailed analyses of issues central to classical music in the present day, including diversity, governance, the identity and perception of classical music, and the challenges facing the achievement of financial stability in non-profit arts organizations. The second part offers case studies, from Miami to Seoul, of the innovative ways in which some arts organizations have responded to the challenges analyzed in the first part. Introductory material, as well as several of the essays, provide some preliminary thoughts about the impact of the crisis year 2020 on the world of classical music. Classical Music Classical Classical Music: Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges will be a valuable and engaging resource for all readers interested in the development of the arts and classical music, especially academics, arts administrators and organizers, and classical music practitioners and audiences. Edited by Paul Boghossian Michael Beckerman Julius Silver Professor of Philosophy Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor and Chair; Director, Global Institute for of Music and Chair; Collegiate Advanced Study, New York University Professor, New York University This is the author-approved edition of this Open Access title. As with all Open Book publications, this entire book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

Htemships Offer Popular Afternative Creased to 15 Counts in 2008 from Focused on Removing the Veazie 11 in 2007

ALUMNI NEWS \ D1WALI FESTIVAL Campus Kulik '76 crime stats counts published river fish By MICHAEL BROPHY By EMMA CREEDEN ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR CONTRIBUTING WRITER Earlier mis month, College Se- The Penobscot River Restora- curity submitted the College's tion Project is an assertive, ag- 2008 Campus Crime Statistics to gressive, public-private attempt to the U.S. Department of Educa- restore native fish populations in tion and posted the information the Penobscot River. on the Department of Security Over 150 years of land clear- web page. ing, sewage waste and industrial In accordance with federal law, pollution by pulp, paper, textile the report must list the counts for and lumber mills turned the river an array of potential campus into what Brandon Kulik '76 crimes, ranging from burglary all refers to as a "biological desert." the way to murder and arson for The Penobscot River contin- the calendar year of 2008. The ued to succumb to extreme statistics from 2008 are listed amounts of sludge and contami- next to the same statistics for the ¦ nation until the passage of the — CHRIS KASPRA1VTHE CWBY ECHO calendar years 2006 and 2007. Clean Water Act in 1972 and a se- Students danced for a crowd in Foss on Friday to celebrate the holiday of lights. The event featured traditional Indian song and dance. The statistic that stands out ries of hydro quality reforms in most in the report is the signifi- the 1980s. cant increase in larceny, which Today, the Penobscot River increased to 86 counts in 2008 Restoration Project is issuing a from 53 in 2007. -

Strathendrick, and Its Inhabitants from Early

A.BS.o.. National Library of Scotland 11 *B000022713* *. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/strathendrickitsOOsmit STRATHENDRICK THE EDITION OF THIS BOOK FOR SALE IS LIMITED TO FOUR HUNDRED AND FORTY COPIES, OF WHICH EIGHTY-FIVE HAVE ALL THE FULL PAGE ENGRAVINGS IN PROOF ON JAPANESE PAPER. FhntccfraviiEEtrr Annan S_Saas from a Pnafflaropli "by JaTm Smart Hi <^{jQtj£<ruJ* STRATH END RICK AND ITS INHABITANTS FROM EARLY TIMES JU Jtcconnt of the parishes of Jfintru, ^alfron, gttllearn, IBrumen, |5urhanan, anb giUmaronock JOHN GUTHRIE SMITH, F.S.A.Scot. Author of "THE PARISH OF STRATHBLANE " GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS publishers to the StnibersitD 1896 GLASGOW : PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND CO. "W ^ I take this opportunity of thanking all those who have helped in preparing this volume for the press. It is a grief to me that I have not been able to assist in the completion of this, the last work of my father, but at this distance from Scotland, it was out of the question to make an attempt requiring not only intimate acquaintance with the district, but also access to family records, charters, and other relics of the past. On behalf of my brothers and sisters as well as myself I thank all who have taken part in the preparation of 'Strathendrick.' H. GUTHRIE SMITH. Hawkes Bay, New Zealand, Decern her 1895. NOTE. The late Mr. Guthrie Smith had been engaged on this volume since the completion of The Parish of Strathblane in December 1886. -

Hyperreality in Radiohead's the Bends, Ok Computer

HYPERREALITY IN RADIOHEAD’S THE BENDS, OK COMPUTER, AND KID A ALBUMS: A SATIRE TO CAPITALISM, CONSUMERISM, AND MECHANISATION IN POSTMODERN CULTURE A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Attainment of the Sarjana Sastra Degree in English Language and Literature By: Azzan Wafiq Agnurhasta 08211141012 STUDY PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS YOGYAKARTA STATE UNIVERSITY 2014 APPROVAL SHEET HYPERREALITY IN RADIOHEAD’S THE BENDS, OK COMPUTER, AND KID A ALBUMS: A SATIRE TO CAPITALISM, CONSUMERISM, AND MECHANISATION IN POSTMODERN CULTURE A THESIS By Azzan Wafiq Agnurhasta 08211141012 Approved on 11 June 2014 By: First Consultant Second Consultant Sugi Iswalono, M. A. Eko Rujito Dwi Atmojo, M. Hum. NIP 19600405 198901 1 001 NIP 19760622 200801 1 003 ii RATIFICATION SHEET HYPERREALITY IN RADIOHEAD’S THE BENDS, OK COMPUTER, AND KID A ALBUMS: A SATIRE TO CAPITALISM, CONSUMERISM, AND MECHANISATION IN POSTMODERN CULTURE A THESIS By: AzzanWafiqAgnurhasta 08211141012 Accepted by the Board of Examiners of Faculty of Languages and Arts of Yogyakarta State University on 14July 2014 and declared to have fulfilled the requirements for the attainment of the Sarjana Sastra degree in English Language and Literature. Board of Examiners Chairperson : Nandy Intan Kurnia, M. Hum. _________________ Secretary : Eko Rujito D. A., M. Hum. _________________ First Examiner : Ari Nurhayati, M. Hum. _________________ Second Examiner : Sugi Iswalono, M. A. _________________ -

XTC Go 2 Mp3, Flac, Wma

XTC Go 2 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Go 2 Country: Japan Released: 2011 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1613 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1631 mb WMA version RAR size: 1792 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 579 Other Formats: ADX MOD XM ASF MPC WMA MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Meccanik Dancing (Oh We Go!) = メカニック・ダンシング (オー・ウィ・ゴー!) 1 2:35 Written-By – A. Partridge* Battery Brides (Andy Paints Brian) = バッテリー・ブライズ (アンディ・ペインツ・ブライアン) 2 4:36 Written-By – A. Partridge* Buzzcity Talking = バズシティ・トーキング 3 2:41 Written-By – C. Moulding* Crowded Room = クラウデッド・ルーム 4 2:52 Written-By – C. Moulding* The Rhythm = ザ・リズム 5 3:00 Written-By – C. Moulding* Red = レッド 6 3:00 Written-By – A. Partridge* Beatown = ビータウン 7 4:36 Written-By – A. Partridge* Life Is Good In The Greenhouse = ライフ・イズ・グッド・イン・ザ・グリーンハウス 8 4:40 Written-By – A. Partridge* Jumping In Gomorrah = ジャンピング・イン・ゴモラ 9 2:02 Written-By – A. Partridge* My Weapon = マイ・ウェポン 10 2:20 Written-By – B. Andrews* Super-Tuff = スーパー・タフ 11 4:27 Written-By – B. Andrews* I Am The Audience = アイ・アム・ジ・オーディエンス 12 3:38 Written-By – C. Moulding* Bonus Track = ボーナス・トラッ クス Are You Receiving Me? = アー・ユー・レシーヴィング・ミー? 13 3:05 Written-By – A. Partridge* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – EMI Music Japan Inc Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Virgin Records Ltd. Credits Engineer – John Leckie Engineer [Assistant] – Andy Llewelyn*, Haydn Bendall, Jess Sutcliffe, Pete James Management – Ian Reid Performer – Andy Partridge, Barry Andrews, Colin Moulding, Terry Chambers Photography -

Radiohead and the Philosophy of Music

1 Radiohead and the Philosophy of Music Edward Slowik There’s an old joke about a stranger who, upon failing to get any useful directions from a local resident, complains that the local “doesn’t know much.” The local replies, “yeah, but I ain’t lost”. Philosophers of music are kind of like that stranger. Music is an important part of most people’s lives, but they often don’t know much about it—even less about the philosophy that underlies music. Most people do know what music they like, however. They have no trouble picking and choosing their favorite bands or DJs (they aren’t lost). But they couldn’t begin to explain the musical forms and theory involved in that music, or, more importantly, why it is that music is so important to them (they can’t give directions). Exploring the evolution of Radiohead’s musical style and its unique character is a good place to start. Radiohead and Rock Music In trying to understand the nature of music, it might seem that focusing on rock music, as a category of popular music, is not a good choice. Specifically, rock music complicates matters because it brings into play lyrics, that is, a non-musical written text. This aspect of rock may draw people’s attention away from the music itself. (In fact, I bet you know many people who like a particular band or song based mainly on the lyrics—maybe these people should take up poetry instead!) That’s why most introductions to the philosophy of music deal exclusively with classical music, since classical music is often both more complex structurally and contains no lyrics, allowing the student to focus upon the purely musical structural components. -

Colin Greenwood and His Christopher Dean Guitar

Castaway oxfordtimes.co.uk Colin Greenwood and his Christopher Dean guitar Photographs: Antony Moore 8 Oxfordshire Limited Edition September 2013 oxfordtimes.co.uk Castaway hat must it be like, as a member of a young rock band, to go from playing to tiny audiences in Wvillage halls and pubs to touring the USA and performing for audiences of 500 or more — with even more fans queuing around the block? And all in a matter of weeks. Multi-instrumentalist and composer Colin Greenwood, bass player with the iconic Oxford band Radiohead, knows that thrill. And it turns out that the USA has been good to Colin in many other ways — as it was where he met his wife, Molly. So what will Colin want to take to our desert island — and where did his journey to our island begin? “In 1969, my mother Brenda gave birth to me at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. But, until I was 11, we did not stay in one place for very long.” Colin said. “My father Ray served in the Royal Ordinance Corps, so the family moved to Germany and then to Didcot, Suffolk, Abingdon and Oakley. I attended five primary schools.” Where did his interest in music begin? “At home there was always music in the background. My parents’ favourite records were by Burl Ives, Scott Joplin, Simon and Garfunkel and Mozart’s horn concerto,” Colin, 44, said. “The important thing our parents did for my brother Jonny, sister Susan and I was to buy each of us musical instruments and encourage us to learn to play.