Schoenberg and the Gesamtkunstwerk Path to Abstraction By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bryan R. Simms. the Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908–1923

Document generated on 10/01/2021 1:27 p.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Bryan R. Simms. The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908–1923. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ix, 265 pp. ISBN 0-19-512826-5 (hardcover) Robert Falck Volume 21, Number 2, 2001 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014493ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014493ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (print) 2291-2436 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Falck, R. (2001). Review of [Bryan R. Simms. The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908–1923. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ix, 265 pp. ISBN 0-19-512826-5 (hardcover)]. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 21(2), 143–146. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014493ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit des universités canadiennes, 2002 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 21/2(2001) 143 very value system that they outwardly support or (the reverse) reinforce a system that they overtly critique. -

Gustav Mahler : Conducting Multiculturalism

GUSTAV MAHLER : CONDUCTING MULTICULTURALISM Victoria Hallinan 1 Musicologists and historians have generally paid much more attention to Gustav Mahler’s famous career as a composer than to his work as a conductor. His choices in concert repertoire and style, however, reveal much about his personal experiences in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his interactions with cont- emporary cultural and political upheavals. This project examines Mahler’s conducting career in the multicultural climate of late nineteenth-century Vienna and New York. It investigates the degree to which these contexts influenced the conductor’s repertoire and questions whether Mahler can be viewed as an early proponent of multiculturalism. There is a wealth of scholarship on Gustav Mahler’s diverse compositional activity, but his conducting repertoire and the multicultural contexts that influenced it, has not received the same critical attention. 2 In this paper, I examine Mahler’s connection to the crumbling, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century depiction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as united and question whether he can be regarded as an exemplar of early multiculturalism. I trace Mahler’s career through Budapest, Vienna and New York, explore the degree to which his repertoire choices reflected the established opera canon of his time, or reflected contemporary cultural and political trends, and address uncertainties about Mahler’s relationship to the various multicultural contexts in which he lived and worked. Ultimately, I argue that Mahler’s varied experiences cannot be separated from his decisions regarding what kinds of music he believed his audiences would want to hear, as well as what kinds of music he felt were relevant or important to share. -

Academy of Theatre and Dance Theatre

Academy of Theatre and Dance Theatre TechniekTechnical enTheatre Theater - 2828 ScenografieScenography 24 AssociateArts - Associate Degree Degree Academy of Theatre and Dance ProductieProduction PodiumkunstenPodiumkiunsten and Stage Management 2222 TheaterdocentTheatre in Education Verkort 1818 Abbreviated 2 Dance Academy of Theatre and Dance National Ballet Academy Urban Contemporary (JMD) 42 46 Modern Theatre 44 5 O’Clock Class 52 Dance School for New Dance 48 Development (SNDO) Dance in Education 50 DAS Choreography 60 1 Creative team Techniek en Theater 26 Regie Opleiding 20 Uitvoerenden Amsterdamse Toneelschool &Kleinkunstacademie 12 Makers Mime Opleiding 14 Docenten Theaterdocent 16 Masters DAS Theatre 58 Theater Techniek en Theater - 28 Scenografie 24 Associate Degree Academy of Theatre and Dance Productie Podiumkunsten 22 Theaterdocent Verkort 18 1 Nine reasons to study at the Academy of Theatre and Dance Academy of Theatre and Dance The Academy of Theatre and Dance (formerly de Theaterschool) is the Netherlands’ premier training school for all theatre and dance disciplines at bachelor and master’s degree level. As a student, you are the star of our show: we’ve built our courses to service your artistic talent, your ambitions and your dreams. Here are nine reasons why you should study with us. 2 Academy of Theatre and Dance 1 We’re one of a kind! Our academy is the only one of its kind in the Netherlands: we are the only theatre and dance academy in the country with all disciplines and relevant resources under one roof. Students from fifteen specialisms can meet and inspire one another here, break new ground and challenge conventional thinking. -

Dutch National Opera Le Nozze Di Figaro

Gary Cooper The Irresistible A New Documentary by Julia and Clara Kuperberg Maria Cooper Janis, Cooper's daughter, INTERNATIONAL Poorhouse opens up to talk about the acting career of her father Newsletter No48 April - September 2019 AMERICAN TAP A uniquely American story that illustrates the vibrant and powerful nature of a cultural melting pot “At a time when America is ivy films struggling with its cultural identity 2 - when anti-immigrant and nativist sentiment boils over into outright racism and xenophobia - we are compelled to look inward to unpack what it means to be American.” Mark Wilkinson Mark Wilkinson Fights of Nations AMERICAN TAP Performers include Jason Samuel Smith and This documentary by William Henry Lane aka Master Juba, Aida Mark Wilkinson traces Overton Walker, Bill Bojangles Robinson, John W Bubbles, Baby Laurence, Chuck Green, tap dancing from The Copasetics, Gregory Hines, Savion Glover, Ginger Rogers, Anne Miller, Vera its origins, through Ellen and Eleanor Powell. Tap dance experts its evolution, to the and historians round off this entertaining and As we dig into the heritage of American instructive documentary. current form. It is a tap dancing, we discover that elements of our history which have the potential to tear us directed by Mark Wilkinson uniquely American apart - the stigma of slavery and the friction produced by Annunziata Gianzero story that illustrates caused by immigration - are the same forces for Ivy Films Inc. which bind us together and fuel our dynamic the vibrant and society. This shared experience is the cultural running time 58' and 88' Shot in HD fire that forged the art form of tap dancing. -

Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill?

DAVID DREW Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill? The pretexts for the present paper are the author's essays >Der T#g der Ver heissung and the Prophecies of jeremiah<, Tempo, 206 (October 1998), 11- 20, and >Der T#g der Verheissung: Weill at the Crossroads<, 1impo, 208 (April 1999), 335-50. As suggested in the preface to the second essay, the paper is intended to function both as a free-standing entity and as an extended bridge between the last section of the earlier essay and the first section of its successor. According to Meyer Weisgal's detailed account of the origins of The Eter nal Road, Reinhardt had no inkling of his plans until their November 1933 meeting in Paris.1 Weisgal began by outlining the idea of a biblical drama that would for the first time evoke the Old Testan1ent in all its breadth rather than in isolated episodes. At the end of his account, according to Weisgal, Reinhardt sat motionless and in silence before saying »very sim ply<< »But who will be the author of this biblical play and who will write the mu sic?<< . »You are the master<< , I said, ••It is up to you to select them<<. Again there was a long uncomfortable pause and Reinhardt said that he would ask Franz Werfel and Kurt Weill to collaborate with him. With or without prior notice2, the problems inherent in Weisgal's com mission were so complex that Reinhardt would have had good reason for Meyer W. Weisgal, >Beginnings of The Eternal Road<, in: T"he Etemal Road (New York 1937 - programme-book for the production by MWW and Crosby Gaige at the Man hattan Opera House), pp. -

Catalogo Giornate Del Cinema Muto 2011

Clara Bow in Mantrap, Victor Fleming, 1926. (Library of Congress) Merna Kennedy, Charles Chaplin in The Circus, 1928. (Roy Export S.A.S) Sommario / Contents 3 Presentazione / Introduction 31 Shostakovich & FEKS 6 Premio Jean Mitry / The Jean Mitry Award 94 Cinema italiano: rarità e ritrovamenti Italy: Retrospect and Discovery 7 In ricordo di Jonathan Dennis The Jonathan Dennis Memorial Lecture 71 Cinema georgiano / Georgian Cinema 9 The 2011 Pordenone Masterclasses 83 Kertész prima di Curtiz / Kertész before Curtiz 0 1 Collegium 2011 99 National Film Preservation Foundation Tesori western / Treasures of the West 12 La collezione Davide Turconi The Davide Turconi Collection 109 La corsa al Polo / The Race to the Pole 7 1 Eventi musicali / Musical Events 119 Il canone rivisitato / The Canon Revisited Novyi Vavilon A colpi di note / Striking a New Note 513 Cinema delle origini / Early Cinema SpilimBrass play Chaplin Le voyage dans la lune; The Soldier’s Courtship El Dorado The Corrick Collection; Thanhouser Shinel 155 Pionieri del cinema d’animazione giapponese An Audience with Jean Darling The Birth of Anime: Pioneers of Japanese Animation The Circus The Wind 165 Disney’s Laugh-O-grams 179 Riscoperte e restauri / Rediscoveries and Restorations The White Shadow; The Divine Woman The Canadian; Diepte; The Indian Woman’s Pluck The Little Minister; Das Rätsel von Bangalor Rosalie fait du sabotage; Spreewaldmädel Tonaufnahmen Berglund Italianamerican: Santa Lucia Luntana, Movie Actor I pericoli del cinema / Perils of the Pictures 195 Ritratti / Portraits 201 Muti del XXI secolo / 21st Century Silents 620 Indice dei titoli / Film Title Index Introduzioni e note di / Introductions and programme notes by Peter Bagrov Otto Kylmälä Aldo Bernardini Leslie Anne Lewis Ivo Blom Antonello Mazzucco Lenny Borger Patrick McCarthy Neil Brand Annette Melville Geoff Brown Russell Merritt Kevin Brownlow Maud Nelissen Günter A. -

The Baroque. 3.3: Vocal Music: the Da Capo Aria and Other Types of Arias

UNIT 3: THE BAROQUE. 3.3: VOCAL MUSIC: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS EXPLANATION 3.3: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS. THE ARIA The aria in the operas is the part sung by the soloist. It is opposed to the recitative, which uses the recitative style. In the arias the composer shows and exploits the dramatic and emotional situations, it becomes the equivalent of a soliloquy (one person speach) in the spoken plays. In the arias, the interpreters showed their technique, they showed off, even in excess, which provoked a lot of criticism from poets and musicians. They were often sung by castrati: soprano men undergoing a surgical operation so as not to change their voice when they grew up. One of them, the most famous, Farinelli, acquired international fame for his great technique and vocal expression. He lived twenty-five years in Spain. THE DA CAPO ARIA The Da Capo aria is a vocal work in three parts or sections (tripartite form). It began to be used in the Baroque in operas, oratorios and cantatas. The form is A - B - A, the last part being a repetition of the first. 1. The first section is a complete musical entity, that is to say, it could be sung alone and musically it would have complete meaning since it ends in the tonic. The tonic is the first grade or note of a scale. 2. The second section contrasts with the first section in tonality, texture, mood and sometimes in tempo (speed). 3. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

Oscar Straus Beiträge Zur Annäherung an Einen Zu Unrecht Vergessenen

Fedora Wesseler, Stefan Schmidl (Hg.), Oscar Straus Beiträge zur Annäherung an einen zu Unrecht Vergessenen Amsterdam 2017 © 2017 die Autorinnen und Autoren Diese Publikation ist unter der DOI-Nummer 10.13140/RG.2.2.29695.00168 verzeichnet Inhalt Vorwort Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................5 Avant-propos Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................7 Wien-Berlin-Paris-Hollywood-Bad Ischl Urbane Kontexte 1900-1950 Susana Zapke (Wien) ................................................................................................................ 9 Von den Nibelungen bis zu Cleopatra Oscar Straus – ein deutscher Offenbach? Peter P. Pachl (Berlin) ............................................................................................................. 13 Oscar Straus, das „Überbrettl“ und Arnold Schönberg Margareta Saary (Wien) .......................................................................................................... 27 Burlesk, ideologiekritisch, destruktiv Die lustigen Nibelungen von Oscar Straus und Fritz Oliven (Rideamus) Erich Wolfgang Partsch† (Wien) ............................................................................................ 48 Oscar Straus – Walzerträume Fritz Schweiger (Salzburg) ..................................................................................................... 54 „Vm. bei Oscar Straus. Er spielte mir den tapferen Cassian vor; -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

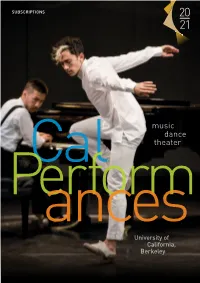

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c.