1 the Impact of the Tenth Mountain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAINING of OFFICERS CANDIDATES CE.S Si ARMY

DRAINING Of OFFICERS CANDIDATES CE.S Si ARMY GROUND FORCES STUDY HO. 31 IISACGSC LIBRARY 1i tfrmiftf TRAINING OF OFFICERS CANDIDATES IN A G F SPECIAL TRAINING SCHOOLS Study No. 31 this dots ("Fiic Sif^ ' 1*7 $0 Historical Section . Army Ground Forces 1946 19 NwV ; S ' LLl*« AJLtiii The Army Ground Forces TRAINING OF OFFICER CANDIDATES IN AGF SPECIAL SERVICE SCHOOLS Study No, 31 By Major William R. Keast Historical Section - Army Ground Forces 1946 B E 3 T E I fc T'E D HEADQUAETERS ARMY GROUND FOECES WASHINGTON 25, D, C. 31^.7(1 Sept 19^o)GNHIS 1 September 19^5 SUBJECT: Studies in the History of Aimy Ground. Forces TO: All Interested Agencies 1. The hist017 of the Array Ground Forces as a command was prepared during the course of the war and completed immediately thereafter. The studies prepared in Headquarters Anny Ground Forces,'were written "by professional historians, three of whom served as commissioned officers, and one as a civilian. The histories of the subordinate commands were prepared by historical officers, who except iii Second Army, acted as such in addition to other duties. 2. From, the first, the histoiy was designed primarily for the Army. Its object is to give an account of what was done from the point of view of the command preparing the histoiy, including a candid, and factual account of difficulties, mistakes recognized as such, the means by which, in the opinion of those concerned, they might have been avoided, the measures used to overcome them, and the effectiveness of such measures. -

Joseph Warren Stilwell Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf958006qb Online items available Register of the Joseph Warren Stilwell papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee, revised by Lyalya Kharitonova Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003, 2014, 2015, 2017 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Joseph Warren 51001 1 Stilwell papers Title: Joseph Warren Stilwell papers Date (inclusive): 1889-2010 Collection Number: 51001 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 93 manuscript boxes, 16 oversize boxes, 1 cubic foot box, 4 album boxes, 4 boxes of slides, 7 envelopes, 1 oversize folder, 3 sound cassettes, sound discs, maps and charts, memorabilia(57.4 Linear Feet) Abstract: Diaries, correspondence, radiograms, memoranda, reports, military orders, writings, annotated maps, clippings, printed matter, sound recordings, and photographs relating to the political development of China, the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945, and the China-Burma-India Theater during World War II. Includes some subsequent Stilwell family papers. World War II diaries also available on microfilm (3 reels). Transcribed copies of the diaries are available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org Creator: Stilwell, Joseph Warren, 1883-1946 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 36-38 and 40 may only be used one folder at a time. Box 39 closed; microfilm use copy available. Boxes 67, 72-73, 113, and 117 restricted; use copies available in Box 116. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

Errors in American Tank Development in World War II Jacob Fox James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2013 The rW ong track: Errors in American tank development in World War II Jacob Fox James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Jacob, "The rW ong track: Errors in American tank development in World War II" (2013). Masters Theses. 215. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/215 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wrong Track: Errors in American Tank Development in World War II Jacob Fox A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2013 ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................... iii Introduction and Historiography ....................................................................... 1 Chapter One: America’s Pre-War tank Policy and Early War Development ....... 19 McNair’s Tank Destroyers Chapter Two: The Sherman on the Battlefield ................................................. 30 Reaction in the Press Chapter Three: Ordnance Department and the T26 ........................................ -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

Section Six: Interpretive Sites Top of the Rockies National Scenic & Historic Byway INTERPRETIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN Copper Mountain to Leadville

Top Of The Rockies National Scenic & Historic Byway Section Six: Interpretive Sites 6-27 INTERPRETIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN INTERPRETIVE SITES Climax Mine Interpretive Site Introduction This section contains information on: • The current status of interpretive sites. • The relative value of interpretive sites with respect to interpreting the TOR topics. • The relative priority of implementing the recommendations outlined. (Note: Some highly valuable sites may be designated “Low Priority” because they are in good condition and there are few improvements to make.) • Site-specific topics and recommendations. In the detailed descriptions that follow, each site’s role in the Byway Interpretive Management Plan is reflected through the assignment of an interpretive quality value [(L)ow, (M)edium, (H) igh], an interpretive development priority [(L)ow, (M)edium, (H)igh], and a recommended designation (Gateway, Station, Stop, Site). Interpretive value assesses the importance, uniqueness and quality of a site’s interpretive resources. For example, the Hayden Ranch has high value as a site to interpret ranching while Camp Hale has high value as a site to interpret military history. Interpretive priority refers to the relative ranking of the site on the Byway’s to do list. High priority sites will generally be addressed ahead of low priority sites. Top Of The Rockies National Scenic and Historic Byway INTERPRETIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN 6-1 Byway sites by interpretive priority HIGH MEDIUM LOW • USFS Office: Minturn • Climax Mine/Freemont Pass • Mayflower Gulch -

USASF Cheer Age Grid

2020-2021 USASF Cheer Age Grid All adjustments in RED indicate a change/addition since the previous season (2019-2020) All adjustments in BLUE indicate a change/addition since the early release in February 2020 We do not anticipate changes but reserve the right to make changes if needed. We will continue to monitor the fluidity of COVID-19 and reassess if need be to help our members. The USASF Cheer and Dance Rules, Glossary, associated Age Grids and Cheer Rules Overview (collectively the “USASF Rules Documents”) are copyright- protected and may not be disseminated to non-USASF members without prior written permission from USASF. Members may print a copy of the USASF Rules Documents for personal use while coaching a team, choreographing or engaging in event production, but may not distribute, post or give a third party permission to post on any website, or otherwise share the USASF Rules Documents. 1 Copyright © 2020 U.S. All Star Federation Released 1.11.21 -Effective 2020-2021 Season 2020-2021 Cheer Age Grid This document contains the division offerings for the 2020-2021 season in the following tiers: • All Star Elite • All Star Elite International • All Star Prep • All Star Novice • All Star FUNdamentals • All Star CheerABILITIES Exceptional Athletes (formerly Special Needs) The age grid provides a "menu" of divisions that may be offered by an individual event producer. An event producer does not have to offer every division listed. However, a USASF member event producer must only offer divisions from the age grids herein and/or combine/split divisions based upon the guidelines herein, unless prior written approval is received from the USASF. -

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY Master's Thesis the M26 Pershing

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY Master’s Thesis The M26 Pershing: America’s Forgotten Tank - Developmental and Combat History Author : Reader : Supervisor : Robert P. Hanger Dr. Christopher J. Smith Dr. David L. Snead A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts In the Liberty University Department of History May 11, 2018 Abstract The M26 tank, nicknamed the “General Pershing,” was the final result of the Ordnance Department’s revolutionary T20 series. It was the only American heavy tank to be fielded during the Second World War. Less is known about this tank, mainly because it entered the war too late and in too few numbers to impact events. However, it proved a sufficient design – capable of going toe-to-toe with vaunted German armor. After the war, American tank development slowed and was reduced mostly to modernization of the M26 and component development. The Korean War created a sudden need for armor and provided the impetus for further development. M26s were rushed to the conflict and demonstrated to be decisive against North Korean armor. Nonetheless, the principle role the tank fulfilled was infantry support. In 1951, the M26 was replaced by its improved derivative, the M46. Its final legacy was that of being the foundation of America’s Cold War tank fleet. Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1. Development of the T26 …………………………………………………..………..10 Chapter 2. The M26 in Action in World War II …………...…………………………………40 Chapter 3. The Interwar Period ……………………………………………………………….63 Chapter 4. The M26 in Korea ………………………………………………………………….76 The Invasion………………………………………………………...………77 Intervention…………………………………………………………………81 The M26 Enters the War……………………………………………………85 The M26 in the Anti-Tank Role…………………………………………….87 Chapter 5. -

Cavendish Town Plan Select Board Hearing Draft January 2018

Cavendish Town Plan Select Board Hearing Draft January 2018 Town of Cavendish P.O. Box 126 Cavendish, Vermont 05142 (802) 226-7292 Document History • Planning Commission hearing and approval of re-adoption of Town Plan with inclusion of Visual Access Map - February 22, 2012 • Select board review of Planning Commission proposed re-adopted town plan with visual access map - April 9, 2012 • Select board review of town plan draft and approval of SB proposed minor modifications to plan – May 14, 2012 • Planning Commission hearing for re-adoption of Town Plan with Select board proposed minor modifications – June 6, 2012 • Planning Commission Approval of Re-adoption of Town Plan with minor modifications – June 6, 2012 • 1st Select board hearing for re-adoption of town plan with minor modifications – June 11, 2012 • 2nd Select board Hearing for re-adoption of Town Plan with minor modifications – August 20, 2012 • Cavendish Town Plan Re-adopted by Australian ballot at Special Town Meeting – August 28, 2012 • Confirmation of Planning Process and Act 200 Approval by the Southern Windsor County Regional Planning Commission – November 27, 2012 • Planning Commission is prepared updates in 2016-2017 This report was developed in 2016 and 2017 for the Town of Cavendish with assistance from the Southern Windsor County Regional Planning Commission, Ascutney, VT. Financial support for undertaking this revision was provided, in part, by a Municipal Planning Grant from the Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development. ii Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Planning Process Summary................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Community and Demographic Trends ............................................................................ -

Camp Hale Story

Camp Hale Story - Wes Carlson Introduction In 1942, the US Army began the construction of a large Army training facility at Pando, Colorado, located in the Sawatch Range at an elevation of 9,250 feet, between Minturn and Leadville, CO, adjacent to US Highway 24. The training facility became known as Camp Hale and eventually housed over 16,000 soldiers. Camp Hale was chosen as it was to become a training facility for mountain combat troops (later known as the 10th Mountain Division) for the US Army in WWII, and the area was in the mountains similar to what the soldiers might experience in the Alps of Europe. The training facility was constructed on some private land acquired by the US Government, but some of the facilities were on US Forest Service land. Extensive cooperation was required by the US Forest Service throughout the construction and operation of the camp and adjacent facilities. The camp occupied over 5,000 acres and was a city in itself. The Camp Site is located in what is now the White River NF. In 2012, at the US Forest Service National Retiree’s Reunion, a tour of the Camp Hale area was arranged. When the group who had signed up for the tour arrived at the office location where the tour was to start, it was announced that we would not be able to go to the Camp Hale site due to logistical issues with the transportation. One retiree, who had signed up for the tour, was very unhappy, and announced that if we couldn’t go to Camp Hale he would like to return to the hotel in Vail. -

Okemo State Forest - Healdville Trail Forest - Healdville Okemo State B

OKEMO STATE FOREST - HEALDVILLE TRAIL North 3000 OKEMO MOUNTAIN RESORT SKI LEASEHOLD AREA OKEMO MOUNTAIN ROAD (paved) 2500 2000 Coleman Brook HEALDVILLE TRAIL 1500 to Ludlow - 5 miles STATION RD railroad tracks HEALDVILLE RD HEALDVILLE VERMONT UTTERMILK F 103 B AL LS RD to Rutland - 16 miles Buttermilk Falls 0 500 1000 2000 3000 feet 1500 LEGEND Foot trail Vista Town highway State highway Lookout tower FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION State forest highway (not maintained Parking area (not maintained in winter) VERMONT in winter) Gate, barricade Stream AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES Ski chairlift Ski area leasehold boundary 02/2013-ephelps Healdville Trail - Okemo State Forest the property in 1935. Construction projects by the CCC The Healdville Trail climbs from the base to the include the fire tower, a ranger’s cabin and an automobile summit of Okemo Mountain in Ludlow and Mount Holly. access road. The majority of Okemo Mountain Resort’s Highlights of this trail include the former fire lookout ski terrain is located within a leased portion of Okemo tower on the summit and a vista along the trail with State Forest. Okemo State Forest is managed for Okemo views to the north and west. Crews from the Vermont multiple uses under a long-term management plan; these Youth Conservation Corps constructed the trail under the uses include forest products, recreation and wildlife direction of the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks habitat. Okemo State Forest provides an important State Forest and Recreation during the summers of 1991-1993. wildlife corridor between Green Mountain National Forest lands to the south and Coolidge State Forest to the Trail Facts north. -

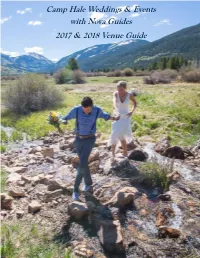

Camp Hale Weddings & Events with Nova Guides 2017 & 2018 Venue Guide

CampCamp Hale Hale Weddings Weddings & Events Venue & GuideEvents with Nova Guides 2017 & 2018 Venue Guide 1 Camp Hale Weddings & Events Venue Guide 2 Camp Hale Weddings & Events Venue Guide Table of Contents… About Camp Hale…………………….4 Ceremony & Reception …………………….5 Venue Pricing …………………….6 Catering Introduction…………………….7 Appetizers…………………….8 Sample Dinner Menus …………………….9-10 Beverage Policies & Packages …………………….11 Beverage Selections …………………….12 Extras……………………13 Testimonials …………………….14 Frequently Asked Questions …………………….15 Venue Coordinator & Contact Information …………………….16 3 Camp Hale Weddings & Events Venue Guide About Camp Hale… Have you dreamed of a true Rocky Mountain Wedding, complete with a waterfront ceremony and a back drop of 12,000 foot mountainous peaks, aspens, and pines? Then Camp Hale is the only wedding venue for you. Historic Camp Hale is nestled within the Pando Valley, only fifteen miles from Vail, Colorado. Once home to 15,000 American Soldiers, Camp Hale is the former training grounds for the 10th Mountain Division, and a National Historic land site. After serving in World War II these men returned and initiated the American Ski Industry, including Vail Mountain. Camp Hale is now a part of the White River National Forest and lends itself to limitless options for outdoor recreation and unforgettable Colorado events. 4 Camp Hale Weddings & Events Venue Guide Ceremony & Reception Spaces... Say your vows amid the serenity of nature on our grassy ceremony island situated in the middle of our five acre private lake on the edge of the White River National Forest. With backdrops of 12,000 foot peaks, meadows, aspens and pines, this setting offers a true Rocky Mountain wedding experience.