The Spiritan Contribution to Education in Igboland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growth of the Catholic Church in the Onitsha Province Op Eastern Nigeria 1905-1983 V 14

THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OP EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 V 14 - I BY REV. FATHER VINCENT NWOSU : ! I i A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY , DEGREE (EXTERNAL), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1988 ProQuest Number: 11015885 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015885 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 s THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OF EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 By Rev. Father Vincent NWOSU ABSTRACT Recent studies in African church historiography have increasingly shown that the generally acknowledged successful planting of Christian Churches in parts of Africa, especially the East and West, from the nineteenth century was not entirely the work of foreign missionaries alone. Africans themselves participated actively in p la n tin g , sustaining and propagating the faith. These Africans can clearly be grouped into two: first, those who were ordained ministers of the church, and secondly, the lay members. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

The Identity of the Catholic Church in Igboland, Nigeria

John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin Faculty of Theology Rev. Fr. Edwin Chukwudi Ezeokeke Index Number: 139970 THE IDENTITY OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN IGBOLAND, NIGERIA Doctoral Thesis in Systematic Theology written under the supervision of Rev. Fr. Dr hab. Krzysztof Kaucha, prof. KUL Lublin 2018 1 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the growth, strength and holiness of the Catholic Church in Igboland and the entire Universal Church. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I give praise and glory to God Almighty, the creator and author of my being, essence and existence. I sincerely thank my Lord Bishop, Most Rev. Paulinus Chukwuemeka Ezeokafor for his paternal blessings, support and sponsorship. With deepest sentiments of gratitude, I thank tremendously my beloved parents, my siblings, my in-laws, friends and relatives for their great kindness and love. My unalloyed gratitude at this point goes to my brother priests here in Europe and America, Frs Anthony Ejeziem, Peter Okeke, Joseph Ibeanu and Paul Nwobi for their fraternal love and charity. My immeasurable gratitude goes to my distinguished and erudite moderator, Prof. Krzysztof Kaucha for his assiduousness, meticulosity and dedication in the moderation of this project. His passion for and profound lectures on Fundamental Theology offered me more stimulus towards developing a deeper interest in this area of ecclesiology. He guided me in formulating the theme and all through the work. I hugely appreciate his scholarly guidance, constant encouragement, thoughtful insights, valuable suggestions, critical observations and above all, his friendly approach. I also thank the Rector and all the Professors at John Paul II Catholic University, Lublin, Poland. -

CHRISTIANITY of CHRISTIANS: an Exegetical Interpretation of Matt

CHRISTIANITY OF CHRISTIANS: An Exegetical Interpretation of Matt. 5:13-16 And its Challenges to Christians in Nigerian Context. ANTHONY I. EZEOGAMBA Copyright © Anthony I. Ezeogamba Published September 2019 All Rights Reserved: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. ISBN: 978 – 978 – 978 – 115 – 7 Printed and Published by FIDES MEDIA LTD. 27 Archbishop A.K. Obiefuna Retreat/Pastoral Centre Road, Nodu Okpuno, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State, Nigeria (+234) 817 020 4414, (+234) 803 879 4472, (+234) 909 320 9690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fidesnigeria.com, www.fidesnigeria.org ii DEDICATION This Book is dedicated to my dearest mother, MADAM JUSTINA NKENYERE EZEOGAMBA in commemoration of what she did in my life and that of my siblings. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge the handiwork of God in my life who is the author of my being. I am grateful to Most Rev. Dr. S.A. Okafor, late Bishop of Awka diocese who gave me the opportunity to study in Catholic Institute of West Africa (CIWA) where I was armed to write this type of book. I appreciate the fatherly role of Bishop Paulinus C. Ezeokafor, the incumbent Bishop of Awka diocese together with his Auxiliary, Most Rev. Dr. Jonas Benson Okoye. My heartfelt gratitude goes also to Bishop Peter Ebele Okpalaeke for his positive influence in my spiritual life. I am greatly indebted to my chief mentor when I was a student priest in CIWA and even now, Most Rev. -

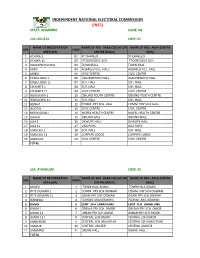

State: Anambra Code: 04

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized RURAL ACCESS AND AGRICULTURAL MARKETING PROJECT (RAAMP) RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Federal Project Management Unit (FPMU) Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development NAIC House, Plot 590, Zone AO, Airport Road, Central Area, Abuja Public Disclosure Authorized May, 2018 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD French Development Agency ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan FPMU Federal Project Management Unit GIS Geographical Information System GPS Global Positioning System LGA Local Government Area NEEDS National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy NPIRD National Policy on Integrated Rural Development NPRTT National Policy on Rural Travel and Transport NTP National Transport Policy PAPs Project Affected Persons PMU Project Management Unit RAAMP Rural Access and Agricultural Marketing Project RAP Resettlement Action Plan RTTP Rural Travel and Transport Policy SEEDS State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy SPIU State Project Implementation Unit WB World Bank 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction The Federal Government of Nigeria has initiated the preparation of the Rural Access and Agricultural Marketing Project (RAAMP) the successor of the Second Rural Access and Mobility Project (RAMP-2). The project will be supported with financing from the World Bank and French Development Agency (AFD) and will be guided by the Government’s Rural Travel and Transport Policy (RTTP). The lead agency for the Federal Government is the Federal Department of Rural Development (FDRD) of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD). The Federal Project Management Unit (FPMU) is overseeing the project on behalf of the FDRD, while the respective selected States Government will be responsible for the implementation of the project. -

(ESMP) for the Amachalla Gully Erosion Site

Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Draft Report Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) for the Amachalla Gully Erosion Site Awka South, Anambra State. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized [Document title] [Document subtitle] Abstract [Draw your reader in with an engaging abstract. It is typically a short summary of the document. When you’re ready to add your content, just click here and start typing.] Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared for the State Project Management Unit (SPMU) Anambra State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project [Email address] Draft Report for the Amachalla gully erosion site Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Draft Report Environmental and Social Management (ESMP) for the Amachalla Gully Erosion Site Awka, Anambra State Prepared for the State Project Management Unit (SPMU) Anambra State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project ii Draft Report for the Amachalla gully erosion site Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................................... IV LIST OF PHOTOS ...................................................................................................................................... V LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................................... V EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. -

EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: the GENDERED STRUGGLE for POWER in SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 by Leonard Ndubueze Mbah a DISSERTAT

EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: THE GENDERED STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 By Leonard Ndubueze Mbah A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: THE GENDERED STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 By Leonard Ndubueze Mbah This dissertation uses oral history, written sources, and emic interpretations of material culture and rituals to explore the impact of changes in gender constructions on the historical processes of socio-political transformation among the Ohafia-Igbo of southeastern Nigeria between 1850 and 1920. Centering Ohafia-Igbo men and women as innovative historical actors, this dissertation examines the gendered impact of Ohafia-Igbo engagements with the Atlantic and domestic slave trade, legitimate commerce, British colonialism, Scottish Christian missionary evangelism, and Western education in the 19th and 20th centuries. It argues that the struggles for social mobility, economic and political power between and among men and women shaped dynamic constructions of gender identities in this West African society, and defined changes in lineage ideologies, and the borrowing and adaptation of new political institutions. It concludes that competitive performances of masculinity and political power by Ohafia men and women underlines the dramatic shift from a pre-colonial period characterized by female bread- winners and more powerful and effective female socio-political institutions, to a colonial period of male socio-political domination in southeastern Nigeria. DEDICATION To the memory of my father, late Chief Ndubueze C. Mbah, my mother, Mrs. Janet Mbah, my teachers and Ohafia-Igbo men and women, whose forbearance made this study a reality. -

List of 2021 Abstracts

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& ABSTRACTS 2021 VIRTUAL IGBO STUDIES ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE &&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& A Aboekwe, Mary Emilia Nwanyi Bu Ihe: In the Light of the Igbo Social World Obielosi, Dominic Department of Religion and Human Relations, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria Aboekwe, Mary Emilia Department of Religion and Society, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam, Anambra State, Nigeria In traditional Igbo social setting, the male child is preferred to the female child. Igbo society is gender sensitive and patriarchal in nature. Even at birth, warm welcome, special recognition is accorded to the male child as against the female counterpart. The male child is perceived as a sustainer of lineage, holder of central and important positions of authority and inheritor of immovable pieces of property. Early in life, the male child is made to feel that he is superior to the female child. Thus, wives wish to give birth to male children as that will properly endear them to their husbands. Husbands are also joyous when their wives give birth to male children. This reassures them that they have someone to take their places after their death, to continue their family line. This paper argues that urbanization has drastically changed this pattern of life. In contemporary society, female children take better and more appropriate care of their parents than the male children. Parents prefer and feel comfortable spending holidays in their daughters’ home than in their male children’s homes. This paper, therefore, draws attention to the changed social situation and the increasing value that is accruing to the girl- child. Key words: Female, male, patriarchy. -

ORAL PERFORMANCE AS SIREN the Example of Ozoemena

ORAL PERFORMANCE AS SIREN Alex Asigbo, PhD The Example of Ozoemena Nwa Nsugbe time. For the people of Omambla1 (old Anambra L.G.A.) various types of music exist. By the nature of Egwu Ekpili music, it is best Alex Asigbo, PhD suited for purposes of extolling virtues and condemning deviance. Theatre Arts Department Nnamdi Azikiwe University This is because, the light instruments allow for maneuverability Awka, Nigeria. hence the musicians can follow whoever is their butt about. It is a form best suited for wandering minstrels in that it requires sparse instruments to complete the ensemble. A typical Egwu Ekpili requires Ekpili (Rattles), Igba (drum), Udu (water pot) and Abstract sometimes Ogidi (long wooden drum) and Ekwe (gong). The Marxist literature pioneered literature of commitment or what practitioners of Egwu Ekpili today are the last of the wandering the French call “Literattu Engage”. Committed literature or art, minstrels. presupposes that a work of art must be devoted to the espousal of It is this nature of Egwu Ekpili that makes it best suited for the a specific ideology; preferably that which furthers the cause of the propagation of new ideas and or condemning of deviant behavior. down-trodden. Marxism influenced and is still influencing the Fully aware of the potentials of his music, Ozoemena was able to works of the second generation Nigerian playwrights or those turn his art into a mercantile venture by pandering to the wishes whose works gained ascendancy in the 1970s. During the 1970s of wealthy clients through placing his wit at their disposal. In also, Afro beat maestro, Fela Anikulapo- Kuti was using his music defending his penchant for praise singing, Ozoemena insists that not only to lampoon the ruling oligarchy but also to raise the people’s a hungry stomach brooks no morals hence he must first fill his consciousness. -

Geochemistry of Fluvio-Tidal Paleogene Litho-Units of Nsugbe

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 7, Issue 2, February-2016 463 ISSN 2229-5518 Geochemistry of Fluvio-Tidal Paleogene Litho- Units of Nsugbe Area, Southeastern Nigeria: Implication for Provenance, Tectonic Setting and Source Area Weathering Etimita Osuwake Omini, Beka Francis Thomas, Etu-Efeotor John Ovwatar Abstract— Rock chemistry is a function of its origin and history. The fluvio-tidal Paleogene litho-units of Nsugbe area are composed dominantly of fine to coarse, poorly to moderately sorted, subangular to subrounded, quartz-rich sands and sandstones that have a relatively high composition of SiO 2 , Al 2O3 and Fe2O3. They are classified into lithicarenite, sublitharenite and quartzarenite with mature polycyclic continental sedimentary rocks that have imprints of plutonic and volcanic rocks from passive and active continental margins source derivation. The CIA and CIW values show that the source area has undergone intense alteration and weathering. This study consolidates and expands the knowledge of provenance and tectonic settings of Paleogene litho-units in Nsugbe area Index Terms— Provenance; weathering; diagenesis, lithostratigraphy, outcrop, sediment, tectonics. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION he chemical composition of the rock is a function of its The Eocene sands are part of the outcropping units of the T history which is dependent on weathering, transportation Niger Delta province [7] and they belong to the Ameki group and diagenesis [1]. The source area of sediments plays a (Table 1). major role in the mineral constituent and chemical TABLE 1 composition [2], [3]. OUTCROPPING UNITS OF THE CENOZOIC NIGER DELTA [7] Immobile trace elements such as Y, Sc, Th, Zr, Cr, Hf, Co Age Lithostratigraphy Units and rare earth elements (REE) are useful indicators of provenance, tectonic settings and geological processes [4]. -

Reactions of the Governments of Nigeria and Biafra to the Role of the Catholic Church in the Nigeria–Biafra War Jacinta C

war & society, Vol. 34 No. 1, February 2015, 65–83 Reactions of the Governments of Nigeria and Biafra to the Role of the Catholic Church in the Nigeria–Biafra War Jacinta C. Nwaka University of Benin, Nigeria The high incidence of confl ict in the world today, and the overwhelming infl uence of religion on man and his society, have resulted in an increasing engagement of religion in confl ict management. However, in spite of its high profi le in managing confl ict, religion can sometimes form a barrier to confl ict resolution. The Nigeria–Biafra war was one of those wars in which religion, as an instrument of confl ict management, played a double-edged sword. This paper examines the reaction of the parties to this confl ict to the role of the Catholic Church in managing the confl ict. The involvement of the Catholic Church in the Nigeria–Biafra war has ever remained one of the highly controversial themes of this war. While the role played by the church appeared to be a welcome development on the part of the Biafran Government, the Federal Military Government of Nigeria (FMG) was against the church and its activities, particularly its relief programme in Biafra during the war. From the available evidence, the church’s relief services, just like those of the International Committee of the Red Cross, were carried out on both sides of the war. The difference was on the level of dependence on it, as well as the degree of its exploitation by the two parties. In addition to its high dependence on the Caritas airlift, the Biafran Government, in its war of propaganda hinged on religion, was out to exploit every available opportunity provided by the church’s relief programme in Biafra.