Linguistic Variation in Starbucks and Dunkin Donuts by Lilah Butler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People & Economic Activity

PEOPLE & ECONOMIC ACTIVITY STARBUCKS An economic enterpise at a local scale Dr Susan Bliss STAGE 6: Geographical investigation ‘Students will conduct a geographical study of an economic enterprise operating at a local scale. The business could be a firm or company such as a chain of restaurants. 1. Nature of the economic enterprise – chain of 5. Ecological dimension restaurants, Starbucks • Inputs: coffee, sugar, milk, food, energy, water, • Overview of coffee restaurants – types sizes and transport, buildings growth. Latte towns, coffee shops in gentrified inner • Outputs: carbon and water footprints; waste. suburbs and coffee sold in grocery stores, petrol stations and book stores. Drive through coffee places • Environmental goals: sustainability.‘Grounds for your and mobile coffee carts. Order via technology-on garden’, green power, reduce ecological footprints demand. Evolving coffee culture. and waste, recycling, corporate social responsibilities, farmer equity practices, Fairtrade, Ethos water, • Growth of coffee restaurant chains donations of leftover food 2. Locational factors 6. Environmental constraints: climate change, • Refer to website for store locations and Google Earth environmental laws (local, national). • Site, situation, latitude, longitude 7. Effects of global changes on enterprise: • Scale – global, national, local prices, trade agreements, tariffs, climate change, competition (e.g. McDonalds, soft drinks, tea, water), • Reasons for location – advantages changing consumer tastes. Growth of organic and • Growth in Asian countries https://www.starbucks. speciality coffees. Future trends – Waves of Coffee com/store- locator?map=40.743095,-95.625,5z Starbucks chain of restaurants 3. Flows Today Starbucks is the largest coffee chain in the world, • People: customers – ages as well as the premier roaster and retailer of specialty • Goods: coffee, milk, sugar, food coffee. -

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 >> CLICK BELOW TO JUMP TO SECTION DISCOUNTER/ APPAREL BEAUTY SUPPLIES DOLLAR STORE OFFICE SUPPLIES SPORTING GOODS SUPERMARKET/ ACTIVE BEVERAGES DRUGSTORE PET/FARM GROCERY/ SPORTSWEAR HYPERMARKET CHILDREN’S BOOKS ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANT BAKERY/BAGELS/ FINANCIAL FAMILY CARDS/GIFTS BREAKFAST/CAFE/ SERVICES DONUTS MEN’S CELLULAR HEALTH/ COFFEE/TEA FITNESS/NUTRITION SHOES CONSIGNMENT/ HOME RELATED FAST FOOD PAWN/THRIFT SPECIALTY CONSUMER FURNITURE/ FOOD/BEVERAGE ELECTRONICS FURNISHINGS SPECIALTY CONVENIENCE STORE/ FAMILY WOMEN’S GAS STATIONS HARDWARE CRAFTS/HOBBIES/ AUTOMOTIVE JEWELRY WITH LIQUOR TOYS BEAUTY SALONS/ DEPARTMENT MISCELLANEOUS SPAS STORE RETAIL 2 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 APPAREL: ACTIVE SPORTSWEAR 2016 2017 CURRENT PROJECTED PROJECTED MINMUM MAXIMUM RETAILER STORES STORES IN STORES IN SQUARE SQUARE SUMMARY OF EXPANSION 12 MONTHS 12 MONTHS FEET FEET Athleta 46 23 46 4,000 5,000 Nationally Bikini Village 51 2 4 1,400 1,600 Nationally Billabong 29 5 10 2,500 3,500 West Body & beach 10 1 2 1,300 1,800 Nationally Champs Sports 536 1 2 2,500 5,400 Nationally Change of Scandinavia 15 1 2 1,200 1,800 Nationally City Gear 130 15 15 4,000 5,000 Midwest, South D-TOX.com 7 2 4 1,200 1,700 Nationally Empire 8 2 4 8,000 10,000 Nationally Everything But Water 72 2 4 1,000 5,000 Nationally Free People 86 1 2 2,500 3,000 Nationally Fresh Produce Sportswear 37 5 10 2,000 3,000 CA -

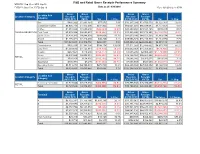

F&B and Retail Gross Receipts Performance Summary

F&B and Retail Gross Receipts Performance Summary MTD PFY: Sep 15 vs. MTD: Sep 16 FYTD PY: Sep 15 vs. FYTD: Sep 16 Data as of: 9/30/2016 Run: 12/1/2016 2:14:15 PM 12:00:00 AM Gross Gross Gross Gross Location Sub Location Category Receipts Receipts Receipts Receipts Category (MTD PFY) (MTD) Var % Chg (FYTD PFY) (FYTD) Var % Chg Bar $985,292 $1,063,164 $77,872 7.9% $10,237,209 $13,559,570 $3,322,361 32.5% Casual Dining/Bar $6,930,743 $7,472,696 $541,952 7.8% $83,051,037 $86,828,087 $3,777,051 4.5% Coffee $1,663,026 $1,620,456 ($42,569) (2.6%) $20,593,466 $21,123,745 $530,279 2.6% FOOD & BEVERAGE Fast Food $3,272,934 $2,653,679 ($619,254) (18.9%) $39,936,206 $37,772,391 ($2,163,816) (5.4%) Quick-Serve $3,439,385 $4,048,054 $608,669 17.7% $42,670,286 $44,553,560 $1,883,274 4.4% Snack $1,276,421 $1,316,689 $40,268 3.2% $15,056,923 $16,218,893 $1,161,970 7.7% Total $17,567,801 $18,174,738 $606,937 3.5% $211,545,128 $220,056,247 $8,511,119 4.0% Convenience $592,130 $1,341,304 $749,174 126.5% $7,511,263 $12,486,622 $4,975,359 66.2% Duty Free $1,203,685 $1,125,314 ($78,370) (6.5%) $15,632,363 $14,753,053 ($879,309) (5.6%) Kiosks $287,657 $118,240 ($169,417) (58.9%) $4,086,286 $2,906,298 ($1,179,988) (28.9%) News $2,597,882 $2,005,573 ($592,309) (22.8%) $32,124,769 $26,461,368 ($5,663,400) (17.6%) RETAIL News/Coffee $793,250 $678,050 ($115,199) (14.5%) $8,686,166 $9,305,677 $619,511 7.1% Spa/Salon $138,982 $7,429 ($131,553) (94.7%) $2,005,669 $541,657 ($1,464,012) (73.0%) Specialty Retail $3,711,278 $4,390,033 $678,755 18.3% $42,200,052 $47,368,052 -

Dissertation (1.448Mb)

Milk revolution and the homogeneous New Zealand coffee market Guo Jingsi 2020 Faculty of Culture and Society A dissertation submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Hospitality Supervisor Dr. Lindsay Neill i Abstract It is unsurprising that, as an enjoyable and social beverage, coffee has generated a coffee culture in Aotearoa New Zealand. Part of coffee’s enjoyment and culture is the range of milk types available for milk-based coffees. That range has grown in recent years. A2 Milk is a recent addition to that offering. The A2 Milk Company has experienced exceptional growth. However, my own experience as a coffee consumer in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, has revealed that A2 Milk is not a milk that is commonly offered in many of the city’s cafés. Consequently, my research explores that lack and barista perceptions of A2 Milk within my research at The Coffee Club in Auckland’s Onehunga. As a franchise outlet, The Coffee Club constitutes a representative sample of a wider cohort, the 60 Coffee Clubs spread throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. While my research reinforces much of the knowledge about coffee culture in Aotearoa New Zealand, my emphasis on the influence of A2 Milk within that culture has revealed some interesting new insights. As my five professional barista participants at the Coffee Club revealed, rather than taking a proactive approach to A2 Milk, they were ‘waiting’ for one of two occurrences before considering the offering of A2 Milk. Those considerations included a ‘push’ from the A2 Milk Company that promoted A2 Milk within coffee culture. -

Growing Types and Interesting Flavors

A COFFEE CLOSEUP; PART 2: GROWING TYPES AND INTERESTING FLAVORS 2018 • TREND INSIGHT REPORT As we mentioned in our first Coffee Closeup (Who, When & Why), coffee consumption in America is not only consistent – it’s consistently high. The average coffee drinker has more than 3 cups each day. In this closeup on coffee, we’ll zero in on the growth and expansion of formats as well as some incredibly unique and innovative flavors hitting the market. WHAT TYPES OF COFFEE ARE CONSUMERS DRINKING? Traditional hot coffee is still the most popular format, however, its losing market share to new coffee types. For example, 21% of consumers claim to have tried cold brew coffee, which is up 6% YTD. Additionally, 8% of consumers have tried flat white varieties, and 5% claim to have tried nitrogen carbonated coffee. Gourmet beverages such as these are driving the increase in past-day coffee consumption. From 2016 to 2017 the number of people reporting having a gourmet coffee drink in the past day rose 10 points from 31% to 41%. What is a Flat White? Espresso-based beverages such as a flat white are driving past-day coffee consumption. So what exactly is a flat white? It’s an espresso-based beverage prepared by pouring steamed milk over a shot of espresso. Starbucks features a seasonal holiday drink called a Holiday Spice Flat White that returned for a third year. It features Ristretto shots of (concentrated) espresso infused with warm holiday spices AT-HOME PREPARATION “subtle enough to let the coffee really shine through,” according to bustle.com, resulting in a less sweet “experience DRIP COFFEE MAKER 46% (for true coffee lovers) that shouldn’t be missed.” SINGLE-CUP BREWER 29% ESPRESSO Heyday Strong & Smooth Espresso Cold- Brew Coffee is described as strong and super Espresso, which chef and food scientist Matthew smooth. -

Tampa, Florida (The “Property”)

CHIPOTLE / STARBUCKS T A M P A, FLORIDA EXCLUSIVE OFFERING DISCLAIMER This Offering Memorandum has been prepared by Owner Representative Additional information and an opportunity to inspect the property will be made (“OREP”) for use by a limited number of parties to evaluate the potential available to interested and qualified prospective investors upon written request. acquisition of Chipotle / Starbucks, Tampa, Florida (the “Property”). All Owner and OREP each expressly reserve the right, at their sole discretion, to projections have been developed by OREP, Owner and designated sources, reject any or all expressions of interest or offers regarding the property and/or are based upon assumptions relating to the general economy, competition, and terminate discussions with any entity at any time with or without notice. Owner other factors beyond the control of OREP and Owner, and therefore are subject shall have no legal commitment or obligations to any entity reviewing this to variation. No representation is made by OREP or Owner as to the accuracy Offering Memorandum or making an offer to purchase the property unless and or completeness of the information contained herein, and nothing contained until such offer is approved by Owner, a written agreement for the purchase herein is or shall be relied on as a promise or representation as to the future of the property has been fully executed, delivered and approved by Owner performance of the Property. Although the information contained herein has and its legal counsel, and any obligations set by Owner thereunder have been been obtained from sources deemed to be reliable and believed to be correct, satisfied or waived. -

Company Factsheet

Starbucks Company Profile January 2019 The Starbucks Story Our story began in 1971. Back then we were a roaster and retailer of whole bean and ground coffee, tea and spices with a single store in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. Today, we are privileged to connect with millions of customers every day in 78 markets. Folklore Starbucks is named after the first mate in Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick.” Our logo is also inspired by the sea – featuring a twin-tailed siren from Greek mythology. Starbucks Mission Our mission: to inspire and nurture the human spirit – one person, one cup and one neighborhood at a time. Our Coffee We’ve always believed in serving the best coffee possible. It's our goal for all of our coffee to be grown under the highest standards of quality, using ethical sourcing practices. Our coffee buyers personally travel to coffee farms in Latin America, Africa and Asia to select high-quality beans. And our master roasters bring out the balance and rich flavor of the beans through the signature Starbucks Roast. Our Stores Our stores are a neighborhood gathering place for meeting friends and family. Our customers enjoy quality service, an inviting atmosphere and an exceptional beverage in more than 29,000 stores and immersive Starbucks Reserve™ Roastery locations in Seattle, Shanghai, Milan and New York. Total stores: 29,865 (as of Dec. 30, 2018) Andorra, Argentina, Aruba, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bahamas, Bahrain, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Brunei, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Curacao, Cyprus, -

Starbucks in 2018: Striving for Operational Excellence and Innovation Agility

Rev. ConfirmingRevisedDesignFirstTest Pages File CASE 29 Starbucks in 2018: Striving for Operational Excellence and Innovation Agility Arthur A. Thompson, The University of Alabama ince its founding in 1987 as a modest nine-store friends either at community tables or in lounge operation in Seattle, Washington, Starbucks areas around two fireplaces. Shad become the premier roaster, marketer, • Open 1,000 Starbucks Reserve stores worldwide and retailer of specialty coffees in the world, with to bring premium experiences to customers and over 28,200 store locations in 76 countries as of promote the company’s recently-introduced April 2018 and annual sales that were expected Starbucks Reserve coffees; these locations offered to exceed $24 billion in fiscal year 2018, ending a more intimate small-lot coffee experience and September 30. In addition to its flagship Starbucks gave customers a chance to chat with a barista brand coffees and coffee beverages, Starbucks’ other about all things coffee. The menu at Starbucks brands included Tazo and Teavana teas, Seattle’s Reserve stores included handcrafted hot and cold Best Coffee, Evolution Fresh juices and smoothies, Starbucks Reserve coffee beverages, hot and cold and Ethos bottled waters. Starbucks stores also sold teas, ice cream and coffee beverages, packages of snack foods, pastries, and sandwiches purchased Starbucks Reserve whole bean coffees, and an from a variety of local, regional, and national suppli- assortment of small plates, sandwiches and wraps, ers. In January 2107, Starbucks officially announced desserts, wines, and beer. There were four types of it would: brewing methods for the coffees and teas. • Open 20 to 30 Starbucks Reserve™ Roasteries and • Transform about 20 percent of the compa- Tasting Rooms, which would bring to life the the- ny’s existing portfolio of Starbucks stores into ater of coffee roasting, brewing, and packaging for Starbucks Reserve coffee bars. -

Valuación De Starbucks Corporation

Universidad de San Andrés Escuela de Administración y Negocios Maestría en Finanzas Valuación de Starbucks Corporation Autor: Alejandro J. Ceroleni DNI: 32.100.194 Director de Tesis: Javier P. Epstein Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Diciembre de 2016 Maestría en Finanzas Tesis de Valuación Año 2016 Alejandro Javier Ceroleni Contenido Definiciones, aclaraciones y abreviaciones ................................................................................... 3 Resumen ejecutivo ........................................................................................................................ 5 Descripción del negocio ................................................................................................................ 6 Clasificación de las ventas por tipo de producto ...................................................................... 6 Cadena de valor ......................................................................................................................... 7 Clasificación de las ventas por segmento operativo ................................................................. 8 Clasificación de las ventas según el modelo de crecimiento .................................................... 9 Creación de valor .................................................................................................................... 10 Historia de Starbucks .............................................................................................................. 11 Howard Schultz: visión e influencia en el crecimiento -

F1d2d570d39644e7b46a7de8

STARBUCKS COFFEE ALLERGY INFORMATION This is the information on the main allergens and their derivatives in our products. Depending on your allergy, please select which you prefer. GLUTEN CRUSTACEANS EGGS FISH PEANUTS SOY MILK NUTS CELERY MUSTARD SESAME SULPHITES LUPINS MOLLUSCS COFFEE AND ESPRESSO Caffè Latte with or without ice (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n Caffè Latte with or without ice (with soy milk) n Cappuccino with or without ice (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n Cappuccino with or without ice (with soy milk) n Caffè Mocca with or without ice (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n n Caffè Mocca with or without ice (with soy milk) n n White Mocha (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n n White Mocha (with soy milk) n n Caramel Macchiato with or without ice (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n n n n Caramel Macchiato with or without ice (with soy milk) n n n n Caffè Americano Caffè Americano (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n Caffè Americano (with soy milk) n Espresso n Espresso Macchiato (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n Espresso Macchiato (with soy milk) n Espresso Panna n Pumking Spice Latte (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n Pumking Spice Latte (with soy milk) n n Flat White (with non-fat milk, semi-skimmed milk, whole milk or lactose-free) n Flat White (with soy -

Retail Attraction Survey Results.Pdf

Retail Attraction Survey SurveyMonkey Q1 From what store and city was your last purchase from a retailer that exceeded $200? Answered: 232 Skipped: 11 # RESPONSES DATE 1 Best buy 9/10/2018 10:29 PM 2 Walmart - Jefferson City 8/14/2018 10:28 AM 3 Lowe’s in JC 8/10/2018 12:24 PM 4 Lowes. Jefferson City 8/10/2018 11:13 AM 5 Target - Jefferson City 8/10/2018 10:39 AM 6 multiple items: Walmart JC Stadium 8/10/2018 10:29 AM 7 Dicks 8/10/2018 7:34 AM 8 IKEA St. Louis 8/10/2018 12:48 AM 9 McKnight Tire, Jefferson City Wal-Mart, Jefferson City Sam's, Jefferson City 8/9/2018 11:05 PM 10 Wal-Mart 8/9/2018 4:10 PM 11 IKEA in st Louis 8/9/2018 3:45 PM 12 Best Buy, Jefferson City 8/9/2018 1:20 PM 13 Jefferson City, Lowe’s 8/9/2018 12:48 PM 14 Kohls, Columbia, MO 8/9/2018 11:48 AM 15 Walmart-school supplies and clothes 8/9/2018 10:19 AM 16 Lowe’s, Jefferson City 8/9/2018 10:14 AM 17 Jefferson City, Walmart 8/9/2018 8:59 AM 18 Nordstrom's, St Louis 8/9/2018 8:10 AM 19 Zales. Osage Beach 8/9/2018 6:37 AM 20 Children’s place, build a bear 8/9/2018 6:36 AM 21 Kirklands Branson 8/9/2018 6:31 AM 22 Sams 8/9/2018 5:38 AM 23 JC Mattress in Jefferson City 8/8/2018 11:46 PM 24 Walmart 8/8/2018 9:39 PM 25 Walmart, jefferson city 8/8/2018 8:22 PM 26 Scruggs, Jefferson City, MO 8/8/2018 7:33 PM 27 Lowes 8/8/2018 5:41 PM 28 Kohls, Jefferson City 8/8/2018 4:38 PM 29 Columbia, Soma 8/8/2018 3:51 PM 30 Will West Music & Sound, Lowe's 8/8/2018 11:35 AM 31 Walmart in Jefferson City 8/8/2018 10:28 AM 32 Staples jeff city 8/8/2018 6:08 AM 33 Probably car maintenance and service at Honda dealer in JC 8/7/2018 5:07 PM 34 Chico's Columbia, Missosuri 8/7/2018 3:00 PM 1 / 43 Retail Attraction Survey SurveyMonkey 35 Best Buy Columbia, MO 8/7/2018 2:49 PM 36 Walmart 8/7/2018 2:28 PM 37 Sunglass Hut 8/7/2018 1:00 PM 38 Homegoods 8/7/2018 12:49 PM 39 Walmart 8/7/2018 12:46 PM 40 Columbia Appliance Columbia MO. -

Starbucks Company Profile

Starbucks Company Profile September 2013 The Starbucks Story Our story began in 1971. Back then we were a roaster and retailer of whole bean and ground coffee, tea and spices with a single store in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. Today, we are privileged to connect with millions of customers every day with exceptional products and more than 19,000 retail stores in over 60 countries. Folklore Starbucks is named after the first mate in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Our logo is also inspired by the sea – featuring a twin‐tailed siren from Greek mythology. Starbucks Mission Our mission: to inspire and nurture the human spirit – one person, one cup and one neighborhood at a time. Our Coffee We’ve always believed in serving the best coffee possible. It's our goal for all of our coffee to be grown under the highest standards of quality, using ethical sourcing practices. Our coffee buyers personally travel to coffee farms in Latin America, Africa and Asia to select the highest quality beans. And our master roasters bring out the balance and rich flavor of the beans through the signature Starbucks Roast. Our Stores Our stores are a neighborhood gathering place for meeting friends and family. Our customers enjoy quality service, an inviting atmosphere and an exceptional beverage. Total stores: 19,209* (as of June 30, 2013) Argentina, Aruba, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bahrain, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Curacao, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, El Salvador, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Hong Kong/Macau, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, New Zealand, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Oman, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United States, Vietnam and Wales.