Pakistan's Battleªeld Nuclear Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India-Pakistan Conflict: Records of the Us State Department, February 1963

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICT: RECORDS OF THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT, FEBRUARY 1963-1966 Over 16,000 pages of State Department Central Files on India and Pakistan from 1963 through 1966 make this collection a standard documentary resource for the study of the political relations between India and Pakistan during a crucial period in the Cold War and the shifting alliances and alignments in South Asia. Date Range: 1963-1966 Content: 15,387 images Source Library: U.S. National Archives Detailed Description: Relations with Pakistan have demanded a high proportion of India’s international energies and undoubtedly will continue to do so. India and Pakistan have divergent national ideologies and have been unable to establish a mutually acceptable power equation in South Asia. The national ideologies of pluralism, democracy, and secularism for India and of Islam for Pakistan grew out of the pre-independence struggle between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, and in the early 1990s the line between domestic and foreign politics in India’s relations with Pakistan remained blurred. Because great-power competition—between the United States and the Soviet Union and between the Soviet Union and China—became intertwined with the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India was unable to attain its goal of insulating South Asia from global rivalries. This superpower involvement enabled Pakistan to use external force in the face of India’s superior endowments of population and resources. The most difficult problem in relations between India and Pakistan since partition in August 1947 has been their dispute over Kashmir. -

Zarb-E-Azb and the State of Security in Pakistan

Prof. Dr. Umbreen Javaid1 Zarb-e-Azb and the State of Security in Pakistan Abstract The state of internal security in Pakistan emerged as a challenge to the state-writ due to the societal fragmentation and rise in extremism and terrorism. Incidents of terrorism linked to TTP developed as the major internal security threat in Pakistan. The failure of PML - (N)’s government in bringing the TTP to the dialogue table coupled with a terrifying rise in number of terror attacks on security personal and soft targets led to the hard stance culminating in a comprehensive joint military operation ‘Zarb-e-Azb’ in North Waziristan (FATA) against TTP’s hideouts and their foreign supporters. The paper will focus on the internal security dynamics of Pakistan in post 9/11scanario and the circumstances that led to the massive, large scale military chase in the history of Pakistan [Zarb-e-Azb] to curtail terrorism and to root out extremism. Keywords Internal Security, Operation Zarb-e-Azb, Pakistan, extremism, FATA, terror Introduction Security is a dependent concept, it is complex and seamless in nature, it needs to be defined under specific circumstances and precise condition or it is meaningless unless it is defined under relational mode with a major concept [as power and peace]. As per Kraus & Williams, “security is a derivative concept; it is meaningless in itself. To have any meaning, security necessarily presupposes something to be secured; as a realm of study it cannot be self-referential” (1997: ix). Realist considers security as the sub-derivative of power or some of the theorists consider it parallel to power, while liberalists believe that security is the essential element for retaining peace (Javaid & Kamal, 2015: 116-117). -

June Ank 2016

The Specter of Emergency Continues to Haunt the Country Mahi Pal Singh Forty one years ago this country witnessed people had been detained without trial under the the darkest chapter in the history of indepen- repressive Maintenance of Internal Security Act dent and democratic India when the state of (MISA), several high courts had given relief to emergency was proclaimed on the midnight of the detainees by accepting their right to life and 25th-26th June 1975 by Indira Gandhi, the then personal liberty granted under Article 21 and ac- Prime Minister of the country, only to satisfy cepting their writs for habeas corpus as per pow- her lust for power. The emergency was declared ers granted to them under Article 226 of the In- when Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha of the dian constitution. This issue was at the heart of Allahabad High Court invalidated her election the case of the Additional District Magistrate of to the Lok Sabha in June 1975, upholding Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla, popularly known charges of electoral fraud, in the case filed by as the Habeas Corpus case, which came up for Raj Narain, her rival candidate. The logical fol- hearing in front of the Supreme Court in Decem- low up action in any democratic country should ber 1975. Given the important nature of the case, have been for the Prime Minister indicted in the a bench comprising the five senior-most judges case to resign. Instead, she chose to impose was convened to hear the case. emergency in the country, suspend fundamen- During the arguments, Justice H.R. -

A Look Into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan Over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori

A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/07/a-look-into-the-conflict-between-india-and-pakistan-over-kashmir/ PRANAV ASOORI, OCT 7 2020 The region of Kashmir is one of the most volatile areas in the world. The nations of India and Pakistan have fiercely contested each other over Kashmir, fighting three major wars and two minor wars. It has gained immense international attention given the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers and this conflict represents a threat to global security. Historical Context To understand this conflict, it is essential to look back into the history of the area. In August of 1947, India and Pakistan were on the cusp of independence from the British. The British, led by the then Governor-General Louis Mountbatten, divided the British India empire into the states of India and Pakistan. The British India Empire was made up of multiple princely states (states that were allegiant to the British but headed by a monarch) along with states directly headed by the British. At the time of the partition, princely states had the right to choose whether they were to cede to India or Pakistan. To quote Mountbatten, “Typically, geographical circumstance and collective interests, et cetera will be the components to be considered[1]. -

Ethnomedicinal Profile of Flora of District Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan

ISSN: 2717-8161 RESEARCH ARTICLE New Trend Med Sci 2020; 1(2): 65-83. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ntms Ethnomedicinal Profile of Flora of District Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan Fozia Noreen1*, Mishal Choudri2, Shazia Noureen3, Muhammad Adil4, Madeeha Yaqoob4, Asma Kiran4, Fizza Cheema4, Faiza Sajjad4, Usman Muhaq4 1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan 2Department of Statistics, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan 3Governament Degree College for Women, Malakwal, District Mandi Bahauddin, Punjab, Pakistan 4Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Gujrat Sialkot Subcampus, Punjab, Pakistan Article History Abstract: An ethnomedicinal profile of 112 species of remedial Received 30 May 2020 herbs, shrubs, and trees of 61 families with significant Accepted 01 June 2020 Published Online 30 Sep 2020 gastrointestinal, antimicrobial, cardiovascular, herpetological, renal, dermatological, hormonal, analgesic and antipyretic applications *Corresponding Author have been explored systematically by circulating semi-structured Fozia Noreen and unstructured questionnaires and open ended interviews from 40- Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, 74 years old mature local medicine men having considerable University of Sialkot, professional experience of 10-50 years in all the four geographically Punjab, Pakistan diversified subdivisions i.e. Sialkot, Daska, Sambrial and Pasrur of E-mail: [email protected] district Sialkot with a total area of 3106 square kilometres with ORCID:http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6096-2568 population density of 1259/km2, in order to unveil botanical flora for world. Family Fabaceae is found to be the most frequent and dominant family of the region. © 2020 NTMS. -

Battle of Hajipir (Indo-Pak War 1965)

No. 08/2019 AN INDIAN ARMY PUBLICATION August 2019 BATTLE OF HAJIPIR (INDO-PAK WAR 1965) MAJOR RANJIT SINGH DAYAL, PVSM, MVC akistan’s forcible attempt to annex Kashmir was defeated when India, even though surprised by the Pakistani offensive, responded with extraordinary zeal and turned the tide in a war, Pakistan thought it would win. Assuming discontent in Kashmir with India, Pakistan sent infiltrators to precipitate Pinsurgency against India under ‘OPERATION GIBRALTAR’, followed by the plan to capture Akhnoor under ‘OPERATION GRAND SLAM’. The Indian reaction was swift and concluded with the epic capture of the strategic Haji Pir Pass, located at a height of 2637 meters on the formidable PirPanjal Range, that divided the Kashmir Valley from Jammu. A company of 1 PARA led by Major (later Lieutenant General) Ranjit Singh Dayal wrested control of Haji Pir Pass in Jammu & Kashmir, which was under the Pakistani occupation. The initial victory came after a 37- hour pitched battle by the stubbornly brave and resilient troops. Major Dayal and his company accompanied by an Artillery officer started at 1400 hours on 27 August. As they descended into the valley, they were subjected to fire from the Western shoulder of the pass. There were minor skirmishes with the enemy, withdrawing from Sank. Towards the evening, torrential rains covered the mountain with thick mist. This made movement and direction keeping difficult. The men were exhausted after being in the thick of battle for almost two days. But Major Dayal urged them to move on. On reaching the base of the pass, he decided to leave the track and climb straight up to surprise the enemy. -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Afzal Guru's Execution

Contents ARTICLES - India’s Compass On Terror Is Faulty What Does The Chinese Take Over - Kanwal Sibal 3 Of Gwadar Imply? 46 Stop Appeasing Pakistan - Radhakrishna Rao 6 - Satish Chandra Reforming The Criminal Justice 103 Slandering The Indian Army System 51 10 - PP Shukla - Dr. N Manoharan 107 Hydro Power Projects Race To Tap The ‘Indophobia’ And Its Expressions Potential Of Brahmaputra River 15 - Dr. Anirban Ganguly 62 - Brig (retd) Vinod Anand Pakistan Looks To Increase Its Defence Acquisition: Urgent Need For Defence Footprint In Afghanistan Structural Reforms 21 - Monish Gulati 69 - Brig (retd) Gurmeet Kanwal Political Impasse Over The The Governor , The Constitution And The Caretaker Government In 76 Courts 25 Bangladesh - Dr M N Buch - Neha Mehta Indian Budget Plays With Fiscal Fire 34 - Ananth Nageswaran EVENTS Afzal Guru’s Execution: Propaganda, Politics And Portents 41 Vimarsha: Security Implications Of - Sushant Sareen Contemporary Political 80 Environment In India VIVEK : Issues and Options March – 2013 Issue: II No: III 2 India’s Compass On Terror Is Faulty - Kanwal Sibal fzal Guru’s hanging shows state actors outside any law. The the ineptness with which numbers involved are small and A our political system deals the targets are unsuspecting and with the grave problem of unprepared individuals in the terrorism. The biggest challenge to street, in public transport, hotels our security, and indeed that of or restaurants or peaceful public countries all over the world that spaces. Suicide bombers and car are caught in the cross currents of bombs can cause substantial religious extremism, is terrorism. casualties indiscriminately. Shadowy groups with leaders in Traditional military threats can be hiding orchestrate these attacks. -

Responsible for Deaths of Involvement in Major Terrorist Attacks Designation Hafiz Mohammed Saeed, Amir, Lashkar-E-Taiba And

Responsible Involvement in major terrorist Designation for deaths of attacks . January 1998 Wandhama . Declared as terrorist by India under massacre (23) the amended Unlawful Activities . March 2000 Chittisinghpura (Prevention) Act (UAPA) in Hafiz Mohammed 625 people massacre (35) September 2019; Saeed, Amir, . December 2000 Red Fort attack . Designated as a global terrorist by Lashkar-e-Taiba (3) the UN in December 2008; and Jamaat-ud- . May 2002 Kaluchak massacre . Designated by the US Treasury in Daawa (31) May 2008; . March 2003 Nandimarg . Carries reward up to $10 million massacre (24) from the US Government. Zaki-ur-Rahman . October 2005 Delhi Diwali blasts . Declared as terrorist by India under Lakhvi, (62) the amended UAPA in September Operational . March 2006 Varanasi blasts (28) 2019; Commander, . April 2006 Doda massacre (34) . Designated as a global terrorist by Lashkar-e-Taiba . July 2006 Mumbai train blasts the UN in December 2008; (211) . Designated by the US Treasury in . January 2008 Rampur CRPF May 2008. camp attack (8) . November 2008 Mumbai attack (166) Masood Azhar, 125 people . October 2001 Srinagar Assembly . Declared as terrorist under the Amir, Jaish-e- attack (38) December 2001 amended UAPA in September 2019; Mohammed Parliament attack (9) . Designated by the UN as a global . January 2016 Pathankot attack terrorist in May 2019; (7) . Designated by the US Treasury in . September 2016 Uri attack (19) November 2010. October 2017 Humhama BSF camp attack (1) . December 2017 Lethpora CRPF camp attack (4) . February 2018 Sunjawan attack (7) . February 2019 Lethpora suicide attack (40) Dawood Ibrahim 257 people March 1993 Mumbai serial blasts . -

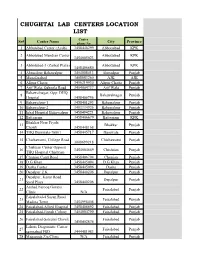

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

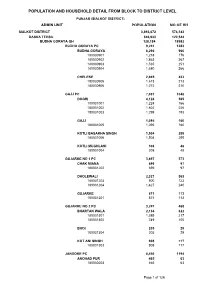

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI