Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnomedicinal Profile of Flora of District Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan

ISSN: 2717-8161 RESEARCH ARTICLE New Trend Med Sci 2020; 1(2): 65-83. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ntms Ethnomedicinal Profile of Flora of District Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan Fozia Noreen1*, Mishal Choudri2, Shazia Noureen3, Muhammad Adil4, Madeeha Yaqoob4, Asma Kiran4, Fizza Cheema4, Faiza Sajjad4, Usman Muhaq4 1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan 2Department of Statistics, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan 3Governament Degree College for Women, Malakwal, District Mandi Bahauddin, Punjab, Pakistan 4Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Gujrat Sialkot Subcampus, Punjab, Pakistan Article History Abstract: An ethnomedicinal profile of 112 species of remedial Received 30 May 2020 herbs, shrubs, and trees of 61 families with significant Accepted 01 June 2020 Published Online 30 Sep 2020 gastrointestinal, antimicrobial, cardiovascular, herpetological, renal, dermatological, hormonal, analgesic and antipyretic applications *Corresponding Author have been explored systematically by circulating semi-structured Fozia Noreen and unstructured questionnaires and open ended interviews from 40- Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, 74 years old mature local medicine men having considerable University of Sialkot, professional experience of 10-50 years in all the four geographically Punjab, Pakistan diversified subdivisions i.e. Sialkot, Daska, Sambrial and Pasrur of E-mail: [email protected] district Sialkot with a total area of 3106 square kilometres with ORCID:http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6096-2568 population density of 1259/km2, in order to unveil botanical flora for world. Family Fabaceae is found to be the most frequent and dominant family of the region. © 2020 NTMS. -

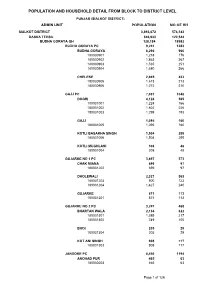

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI -

Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project, Loan No. 3264

Due Diligence Report on Social Safeguards Loan 3264-PAK: Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project (FERRP)–Punjab Roads Component Due Diligence Report on Social Safeguards on Reconstruction of Daska – Pasrur Road March 2017 Prepared by: Communication and Works Department, Government of the Punjab NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This Social Safeguards due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB COMMUNICATION & WORKS DEPARTMENT Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project (FERRP) Social Due Diligence Report of Reconstruction of Daska- Pasrur Road (RD 0+000 – RD 30+000) March, 2017 Prepared by TA Resettlement Specialist for Communication and Works Department, Government of Punjab, Lahore Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 A. Background: ............................................................................................................. -

Data Collection Survey on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Islamic Republic of Pakistan

←ボックス隠してある Pakistan by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Data Collection Survey on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Islamic Republic of Pakistan Data Collection Survey ←文字上 / 上から 70mm on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Pakistan by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Final Report Final Report February 2014 February 2014 ←文字上 / 下から 70mm Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. 4R JR 14-020 ←ボックス隠してある Pakistan by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Data Collection Survey on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Islamic Republic of Pakistan Data Collection Survey ←文字上 / 上から 70mm on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Pakistan by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Final Report Final Report February 2014 February 2014 ←文字上 / 下から 70mm Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. 4R JR 14-020 Data Collection Survey on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Pakistan Final Report Location Map Islamabad Capital Territory Punjab Province Islamic Republic of Pakistan Sindh Province Source: Prepared by the JICA Survey Team based on the map on http://www.freemap.jp/. February 2014 i Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Data Collection Survey on Infrastructure Improvement of Energy Sector in Pakistan Final Report Summary Objectives and Scope of the Survey This survey aims to collect data and information in order to explore the possibility of cooperation with Japan for the improvement of the power sector in Pakistan. The scope of the survey is: Survey on Pakistan’s current power supply situation and review of its demand forecast; Survey on the power development policy, plan, and institution of the Government of Pakistan (GOP) and its related companies; Survey on the primary energy in Pakistan; Survey on transmission/distribution and grid connection; and Survey on activities of other donors and the private sector. -

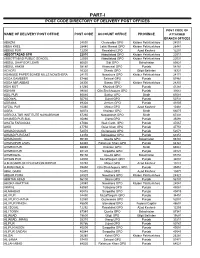

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Sialkot

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT SIALKOT AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ............................................................... i PREFACE ...................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................iv SUMMARY OF TABLES AND CHARTS.................................................. viii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ........................................................................... viii Table 2: Audit observation regarding Financial Management ............................. viii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ............................................................................... viii Table 4: Table of Irregularities Pointed Out ......................................................... ix Table 5: Cost-Benefit .......................................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 District Government, Sialkot ......................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction of Departments .......................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ............................... 1 1.1.3 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance on MFDAC Audit Paras of Audit Report -

MDP-Sialkot-17Th Sep 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: SIALKOT, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17th, 2014 Rains/Floods 2014: Sialkot District Profile September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionR ajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Sr. No. Police Station Phone No. Population (2014 est) 4,017,821 Circles/ Circles/ 1 SDPO City (Circle) 0092-52-9250346 Male 2,061,052 (51%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- 2 Kotwali 0092-52-9250341-2 Tapas urban populated Female 1,956,769 (49%) 3 Civil Lines 0092-52-9250331-3 DISTRICT 22 302 1578 1401 35 30 11 101 Rural 2,965,481 (74%) 4 Cantt 0092-52-9250343-4 SIALKOT 7 98 576 479 22 13 11 51 Urban 1,052,340 (26%) TEHSIL 5 Rang Pura 0092-52-4583001 Tehsils 4 PASROOR 7 99 597 542 10 11 34 6 Neka Pura 0092-52-4592760 UC 129 DASKA 5 67 250 238 2 4 6 7 Haji Pura 0092-52-3553613 Revenue Villages 1,431 SAMBRIAL 3 38 155 142 1 2 10 8 Police Post Suchait Garh (P.S. Cantt) 0092-52-3206111 Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 Area (Sq km) 3,061 9 SDPO Sadar (Circle) 0092-52-3251111 Registered Voters (ECP) 1,061,843 10 Sadar Sialkot 0092-52-3542969 Road Network Infrastructure Literacy Rate 10+ (PSLM 2010-11) 66% District Route Length 11 Uggoki 0092-52-3570484 Sialkot to Narowal Pasrur road 53 Km 12 Murad Pur 0092-52-3562450 Departmental Focal Points Sialkot to Gujranwala Gujranwala road 45 Km 13 Kotli Loharan 0092-52-3533133 Title Phone Fax/Email Sialkot to Wazirabad Wazirabad road 46 Km 14 Kotli Said -

Disaster Risk Management Plan District Sialkot Government of Punjab

Disaster Risk Management Plan District Sialkot Government of Punjab November, 2008 District Disaster Management Authority DCO Office Sialkot Phone: 0092 9250451 Fax:0092 9250453 pyright © Provincial Disaster Management Authority, Punjab Material in this publication may be freely quoted, but acknowledgement is requested. Technical Assistance: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Conceptualized by: Mr. Zubair Murshed Plan Developed by: Mr. Amjad Gulzar Reviewed & Edited by: Mr Shalim Kamran Dost The Plan is available from: a. District Disaster Management Authority, DCO Office Sialkot Phone: 0092 52 9250451 Fax: 0092 52 9250453 b. National Disaster Management Authority Prime Minister's Secretariat Islamabad Phone: 0092 51 9222373 Fax 0092 51 9204197 c. Provincial Disaster Management Authority Lahore Phone: 042-9204404 Fax: 042-9204405 The Plan can also be downloaded from: http//www.ndma.gov.pk Table of Contents Page 7 Foreword 9 Message by DG PDMA 11 Message by DCO Sialkot 13 Message by District Nazim 15 Vision Mission and Objectives 17 Commonly Used Terms and Concepts 21 Acknowledgment 23 25 Abbreviations 27 Distribution of Copies 29 Introduction Purpose of Plan Section 1 Overview of the District 31 1.1 The District Sialkot 31 31 1.2 Geographical Features 31 1.3 Climate and Rainfall 32 1.4 Area, Population and Villages of the District 33 1.5 Health and Education Statistics 33 1.6 Economy 1.6.1 Industry 33 1.6.2 Agriculture (Cropping Pattern, Irrigation, Livestock) 33 Section 2: Disaster -

SIALKOT, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE for RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 12Th, 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: SIALKOT, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 12th, 2014 th Rains/Floods 2014: Sialkot District Profile 12 September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionRajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Sr. No. Police Station Phone No. Population (2014 est) 4,017,821 Circles/ Circles/ 1 SDPO City (Circle) 0092-52-9250346 Male 2,061,052 (51%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- 2 Kotwali 0092-52-9250341-2 Tapas urban populated Female 1,956,769 (49%) 3 Civil Lines 0092-52-9250331-3 DISTRICT 22 302 1578 1401 35 30 11 101 Rural 2,965,481 (74%) 4 Cantt 0092-52-9250343-4 SIALKOT 7 98 576 479 22 13 11 51 Urban 1,052,340 (26%) TEHSIL 5 Rang Pura 0092-52-4583001 Tehsils 4 PASROOR 7 99 597 542 10 11 34 6 Neka Pura 0092-52-4592760 UC 129 DASKA 5 67 250 238 2 4 6 7 Haji Pura 0092-52-3553613 Revenue Villages 1,431 SAMBRIAL 3 38 155 142 1 2 10 8 Police Post Suchait Garh (P.S. Cantt) 0092-52-3206111 Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 Area (Sq km) 3,061 9 SDPO Sadar (Circle) 0092-52-3251111 Registered Voters (ECP) 1,061,843 10 Sadar Sialkot 0092-52-3542969 Road Network Infrastructure Literacy Rate 10+ (PSLM 2010-11) 66% District Route Length 11 Uggoki 0092-52-3570484 Sialkot to Narowal Pasrur road 53 Km 12 Murad Pur 0092-52-3562450 Departmental Focal Points Sialkot to Gujranwala Gujranwala road 45 Km 13 Kotli Loharan 0092-52-3533133 Title Phone Fax/Email Sialkot to Wazirabad Wazirabad road 46 Km 14 Kotli -

Unclaimed Accounts List 2005

National Bank of Pakistan Regional Headquarters, Sialkot UN-CLAIMED ACCOUNTS - SECTION 31 OF BCO, 1962: S.No. Name of Branch. Name of Province Name and address of the Depositor. Account No. Amount Transferred to Nature of Account, Amount reported in where is Branch SBP. Current/Savings/Fixed or Form XI as on 31st located. others. December (years) 1 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Mansaf Ali 3207 32156.00 PLs Savings. 1999 2 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Faqir Khan. 505 8830.00 PLs Savings. 1999 3 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Inayat Ullah. 5623 12491.00 PLs Savings. 1999 4 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Muhammad Shaif. 2500 5764.30 PLs Savings. 1999 5 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Abdul Majeed. 105 77132.04 PLs Savings. 1999 6 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Muhammad Asghar. 655 19875.04 PLs Savings. 1999 7 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Jahan Khan. 2432 18416.45 PLs Savings. 1999 8 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Muhammad Bashir. 5346 20682.39 PLs Savings. 1999 9 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Union Committee. 3203 6176.88 PLs Savings. 1999 10 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Union Committee. 324 44137.59 PLs Savings. 1999 11 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Rehmat Ali. 6637 7306.48 PLs Savings. 1999 12 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Shakila Bibi. 8422 8850.00 PLs Savings. 1999 13 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Zulifqar Hussain DD Advice. 121694.52 D.D.No. 308586 1999 14 Main Branch, Daska. Punjab. Abdul Basit. DD advice. 18000.00 D.D.No. 439398 1999 15 Main Branch, Narowal. Punjab. ADLG Narowal. A/c. M/s. M. Ilyas. CD 484148 8050.00 Call Deposit Account. -

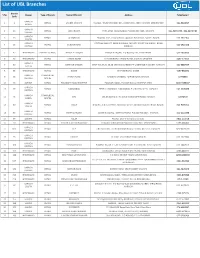

To Download UBL Branch List

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI.