Reparations Or Atonement?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bengal Famine of 1943: Misfortune Or Imperial Schema

cognizancejournal.com Dr. S D Choudhury, Cognizance Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol.1, Issue.5, May 2021, pg. 15-21 ISSN: 0976-7797 The Bengal Famine of 1943: Misfortune or Imperial Schema Dr. S D Choudhury Associate Professor, Department of History, J N College, India [email protected] DOI: 10.47760/cognizance.2021.v01i05.002 Abstract— Bengal famine resulted from food scarcity caused by large-scale exports of food from India for use in the war theatres and consumption in Britain. India exported more than 70,000 tonnes of rice between January and July 1943, even as the famine set in. This would have kept nearly 400,000 people alive for an entire year. Churchill turned down fervent pleas to export food to India, citing a shortage of ships - this when shiploads of Australian wheat, for example, would pass by India to be stored for future consumption in Europe. As imports dropped, prices shot up, and hoarders made a killing. Mr Churchill also pushed a scorched earth policy - which went by the sinister name of Denial Policy - in coastal Bengal, where the colonisers feared the Japanese would land. So, authorities removed boats (the region's lifeline), and the police destroyed and seized rice stocks. During the 1873-'74 famine, the Bengal lieutenant governor, Richard Temple, saved many lives by importing and distributing food. But the British government criticised him and dropped his policies during the drought of 1943, leading to countless fatalities. Keywords— Bengal, British, Churchill, famine, drought, peasants, starvation "I hate Indians. They are beastly people with a beastly religion. -

Subject Index

Economic and Political Weekly INDEX Vol XLV Nos 1-52 January-December 2010 Ed = Editorials MMR = Money Market Review F = Feature RA= Review Article CL = Civil Liberties SA = Special Article C = Commentary D = Discussion P = Perspectives SS = Special Statistics BR = Book Review LE = Letters to Editor SUBJECT INDEX ACADEMICIANS Who Cares for the Railways? (Ed) Social Science Writing in Marathi; Mahesh Issue no: 30, Jul 24-30, p.08 Gavaskar (C) Issue no: 36, Sep 04-10, p.22 Worker Deaths; Moushumi Basu and Asish Gupta (LE) ACADEMY Issue no: 37, Sep 11-17, p.5 Noor Mohammed Bhatt; Moushumi Basu and Asish Gupta (LE) ADDICTION Issue no: 52, Dec 25-31, p.5 A Case for Opium Dens; Vithal Rajan (LE) ACCIDENTAL DEATHS Issue no: 18, May 01-07, p.5 The Bhopal Catastrophe: Politics, Conspiracy and Betrayal; Colin ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS Gonsalves (P) K N Raj and the Delhi School; J Issue no: 26-27, Jun 26-Jul 09, p.68 Krishnamurty (F) Issue no: 11, Mar 13-19, p.67 Bhopal Gas Leak Case: Lost before the Trial; Sriram Panchu (C) ADOPTION LAW Issue no: 25, Jun 19-25, p.10 Expanding Adoption Rights (Ed) Issue no: 35, Aug 28-Sep 03, p.8 Chronic Denial of Justice (LE) Issue no: 24, Jun 12-18, p.07 AFGHANISTAN Exposure of War Crimes (Ed) Conspiracy to Implicate Maoists; Azad Issue no: 31, Jul 31-Aug 06, p.08 (LE) Issue no: 24, Jun 12-18, p.05 AGRARIAN REFORMS A Critical Review of Agrarian Reforms Gyaneshwari Express Sabotage - I; Asish in Sikkim; Anjan Chakrabarti (C) Gupta and Moushumi Basu (LE) Issue no: 05, Jan 30-Feb 05, p.23 Issue no: 23, Jun 05-11, p.04 -

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946 By Janam Mukherjee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) In the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Barbara D. Metcalf, Chair Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Stuart Kirsch Associate Professor Christi Merrill 1 "Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiseling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme - the figures of the deprived, the destitute and the abandoned converging on us from all directions. The first chalk marks of famine that had passed from the fingers to engrave themselves on the heart persist indelibly." 2 Somnath Hore 1 Somnath Hore. "The Holocaust." Sculpture. Indian Writing, October 3, 2006. Web (http://indianwriting.blogsome.com/2006/10/03/somnath-hore/) accessed 04/19/2011. 2 Quoted in N. Sarkar, p. 32 © Janam S. Mukherjee 2011 To my father ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my father, Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee, without whom this work would not have been written. This project began, in fact, as a collaborative effort, which is how it also comes to conclusion. His always gentle, thoughtful and brilliant spirit has been guiding this work since his death in May of 2002 - and this is still our work. -

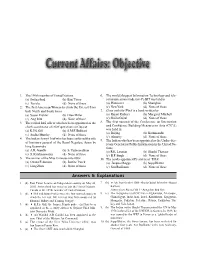

Higher Secondary: SET

RRB PSC Higher Secondary: SET 1. The 190th member of United Nations 6. The world’s biggest Information Technology and tele- (a) Switzerland (b) East Timor communications trade fair-Ce BIT was held in (c) Tuvalu (d) None of these (a) Hannover (b) Shanghai 2. The first American Woman to climb the Everest from (c) New York (d) None of these both North and South faces 7. Gone with the Wind is a book written by (a) Susan Ershler (b) Ellen Miller (a) Rajani Kothari (b) Margaret Mitchell (c) Ang Rita (d) None of these (c) Sheila Gujral (d) None of these 3. The retired IAS officer who has been appointed as the 8. The first summit of the Conference on Interaction chief co-ordinator of relief operations in Gujarat and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) (a) K.P.S. Gill (b) S.M.F. Bokhari was held in (a) Beijing (b) Kathmandu (c) Sudha Murthy (d) None of these (c) Almatty (d) None of these 4. The Indian Army Chief who has been conferred the title 9. The Indian who has been appointed as the Under-Sec- of honorary general of the Royal Nepalese Army by retary General for Public Information in the United Na- king Gyanendra tions. (a) A.R. Gandhi (b) S. Padmanabhan (a) R.K. Laxman (b) Shashi Tharoor (c) S. Krishnaswamy (d) None of these (c) B.P. Singh (d) None of these 5. The winner of the Miss Universe title 2002 10. The newly appointed President of ‘FIFA’ (a) Oxana Fedorova (b) Justine Pasek (a) Jacques Rogge (b) Sepp Blatter (c) Ling Zhou (d) None of these (c) Sen Ruffianne (d) None of these Answers & Explanations 1. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Churchill's Dark Side

Degree Programme: Politics with a Minor (EUUB03) Churchill’s Dark Side To What Extent did Winston Churchill have a Dark Side from 1942-1945? Abstract 1 Winston Churchill is considered to be ‘one of history's greatest leaders; without his 1 leadership, the outcome of World War II may have been completely different’0F . This received view has dominated research, subsequently causing the suppression of Churchill’s critical historical revisionist perspective. This dissertation will explore the boundaries of the revisionist perspective, whilst the aim is, simultaneously, to assess and explain the extent Churchill had a ‘dark side’ from 1942-1945. To discover this dark side, frameworks will be applied, in addition to rational and irrational choice theory. Here, as part of the review, the validity of rational choice theory will be questioned; namely, are all actions rational? Hence this research will construct another viewpoint, that is irrational choice theory. Irrational choice theory stipulates that when the rational self-utility maximisation calculation is not completed correctly, actions can be labelled as irrational. Specifically, the evaluation of the theories will determine the legitimacy of Churchill’s dark actions. Additionally, the dark side will be 2 3 assessed utilising frameworks taken from Furnham et al1F , Hogan2F and Paulhus & 4 Williams’s dark triad3F ; these bring depth when analysing the presence of a dark side; here, the Bengal Famine (1943), Percentage Agreement (1944) and Operation 1 Matthew Gibson and Robert J. Weber, "Applying Leadership Qualities Of Great People To Your Department: Sir Winston Churchill", Hospital Pharmacy 50, no. 1 (2015): 78, doi:10.1310/hpj5001-78. -

Current Affairs Questions and Answers for February 2010: 1. Which Bollywood Film Is Set to Become the First Indian Film to Hit T

ho”. With this latest honour the Mozart of Madras joins Current Affairs Questions and Answers for other Indian music greats like Pandit Ravi Shankar, February 2010: Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayak and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt who have won a Grammy in the past. 1. Which bollywood film is set to become the first A. R. Rahman also won Two Academy Awards, four Indian film to hit the Egyptian theaters after a gap of National Film Awards, thirteen Filmfare Awards, a 15 years? BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe. Answer: “My Name is Khan”. 9. Which bank became the first Indian bank to break 2. Who becomes the 3rd South African after Andrew into the world’s Top 50 list, according to the Brand Hudson and Jacques Rudoph to score a century on Finance Global Banking 500, an annual international Test debut? ranking by UK-based Brand Finance Plc, this year? Answer: Alviro Petersen Answer: The State Bank of India (SBI). 3. Which Northeastern state of India now has four HSBC retain its top slot for the third year and there are ‘Chief Ministers’, apparently to douse a simmering 20 Indian banks in the Brand Finance® Global Banking discontent within the main party in the coalition? 500. Answer: Meghalaya 10. Which country won the African Cup of Nations Veteran Congress leader D D Lapang had assumed soccer tournament for the third consecutive time office as chief minister on May 13, 2009. He is the chief with a 1-0 victory over Ghana in the final in Luanda, minister with statutory authority vested in him. -

Les Ombres Du Bengale

1947-2017 L’Inalco commémore le 70ème anniversaire des indépendances en Asie du Sud (Inde, Pakistan, le Pakistan oriental devenu en 1971 l’actuel Bangladesh) « les Ombres du Bengale » raconte un épisode méconnu de la seconde guerre mondiale : la famine de 1943 au Bengale Occidental et dans l’actuel Bangladesh au cours de laquelle entre 3 et 5 millions de personnes sont mortes de faim. Des historiens anglais et indiens pointent la responsabilité du gouvernement britannique dirigé par Winston Churchill dans cette tragédie. En présence des réalisateurs Joy Banerjee et Partho Bhattacharya Présentation par Anne Viguier, Maître de conférences en histoire, département Asie du Sud et Himalaya, Inalco Jeudi 9 novembre 2017 Contacts 18h30 [email protected] [email protected] dans l’auditorium du Pôle des Langues et Civilisations Entrée libre 65 rue des Grands Moulins - 75013 Paris Métro 14 et RER C Bibliothèque François Mitterrand Les Ombres du Bengale Un film de Joy Banerjee et Partho Bhattacharya Durée : 48 minutes. Version française et anglaise . Format de diffusion : full HD Contact : [email protected] Les Ombres du Bengale raconte un épisode méconnu de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale : la famine de 1943 au cours de laquelle entre 3 et 5 millions de personnes sont mortes de faim au Bengale occidental et dans l'actuel Bangladesh. Une tragédie dont témoignent des artistes comme Chittaprosad Bhattacharya et Zainul Abedin. Aujourd'hui, des historiens, chercheurs, écrivains, aussi bien Anglais qu' Indiens accusent l'Empire britannique d'être responsable de cette famine durant la colonisation du sous-continent. Certains pointent directement la responsabilité de Winston Churchill et parlent même de crime contre l'humanité...Cet épisode révèle une face cachée du Lion Britannique. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Solidarity Statement Against Police Brutality at Jamia Millia Islamia University and Aligarh Muslim University

Solidarity Statement Against Police Brutality at Jamia Millia Islamia University and Aligarh Muslim University We, the undersigned, condemn in the strongest possible terms the police brutality in Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi, and the ongoing illegal siege and curfew imposed on Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. On 15th December 2019 Delhi police in riot-gear illegally entered the Jamia Millia campus and attacked students who are peacefully protesting the Citizenship Amendment Act. The Act bars Muslims from India’s neighboring countries from the acquisition of Indian citizenship. It contravenes the right to equality and secular citizenship enshrined in the Indian constitution. On the 15th at JMIU, police fired tear gas shells, entered hostels and attacked students studying in the library and praying in the mosque. Over 200 students have been severely injured, many who are in critical condition. Because of the blanket curfew and internet blockage imposed at AMU, we fear a similar situation of violence is unfolding, without any recourse to the press or public. The peaceful demonstration and gathering of citizens does not constitute criminal conduct. The police action in the Jamia Millia Islamia and AMU campuses is blatantly illegal under the constitution of India. We stand in unconditional solidarity with the students, faculty and staff of Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University, and express our horror at this violent police and state action. With them, we affirm the right of citizens to peaceful protest and the autonomy of the university as a non-militarized space for freedom of thought and expression. The brutalization of students and the attack on universities is against the fundamental norms of a democratic society. -

Indian Writing in English

INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH Contents 1) English in India 3 2) Indian Fiction in English: An Introduction 6 3) Raja Rao 32 4) Mulk Raj Anand 34 5) R K Narayan 36 6) Sri Aurobindo 38 7) Kamala Markandaya’s Indian Women Protagonists 40 8) Shashi Deshpande 47 9) Arun Joshi 50 10) The Shadow Lines 54 11) Early Indian English Poetry 57 a. Toru Dutt 59 b. Michael Madusudan Dutta 60 c. Sarojini Naidu 62 12) Contemporary Indian English Poetry 63 13) The Use of Irony in Indian English Poetry 68 14) A K Ramanujan 73 15) Nissim Ezekiel 79 16) Kamala Das 81 17) Girish Karnad as a Playwright 83 Vallaths TES 2 English in India I’ll have them fly to India for gold, Ransack the ocean for oriental pearl! These are the words of Dr. Faustus in Christopher Marlowe’s play Dr Faustus. The play was written almost in the same year as the East India Company launched upon its trading adventures in India. Marlowe’s words here symbolize the Elizabethan spirit of adventure. Dr. Faustus sells his soul to the devil, converts his knowledge into power, and power into an earthly paradise. British East India Company had a similar ambition, the ambition of power. The English came to India primarily as traders. The East India Company, chartered on 31 December, 1600, was a body of the most enterprising merchants of the City of London. Slowly, the trading organization grew into a ruling power. As a ruler, the Company thought of its obligation to civilize the natives; they offered their language by way of education in exchange for the loyalty and commitment of their subjects. -

January 2021)

MONTHLY CURRENT AFFAIRS FACTS COMPILATION (JANUARY 2021) 2021 is the International Year - For the Elimination of Child Labor Of Fruits and Vegetables Of Peace and Trust Of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development Important Days of January World Braille Day - January 4 World Day of War Orphans - January 6 Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (NRI Day) - January 9 National Human Trafficking Awareness Day - January 11 World Hindi Day is observed annually on - January 10 National Youth Day - January 12 Armed Forces Veterans Day - January 14 Army Day - January 15 World Religion Day - January 17 National Road Safety Month 2021 - 18 January to 17 February Parakram Diwas - January 23 National Girl Child Day - January 24 International Day of Education - January 24 National Tourism Day - January 25 National Voters Day - January 25 Republic Day - January 26 International Customs Day - January 26 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust - January 27 Martyr’s Day or Shaheed Diwas - January 30 World Leprosy Day - Last Sunday of January (January 31, 2021) National India’s first pollinator park opens in - Uttarakhand India’s first city to have fulfilled 100% of its energy needs during day time with solar energy - Diu Corona virus vaccine developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca - Covishield The COVID-19 vaccine which was recently approved by WHO for immediate use - Pfizer BioNTech vaccine Two vaccines recently approved by the Drugs Controller General of India for “Restricted Emergency Use” in India - COVAXIN and COVISHIELD Which state government recently announced to set up a Tamil Academy to protect the Tamil language and culture? - Delhi The Indian city hosting the India-France joint Rafale Mega Air Exercise ‘SKYROS’ - Jodhpur The largest floating solar energy project in the world is to be constructed by the Govt.