4. the Great Migration, 1871-1890

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Relief Programs in the 19Th Century: a Reassessment

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 19 Issue 3 September Article 8 September 1992 Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment Frank M. Loewenberg Bar-Ilan University, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social History Commons, Social Work Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Loewenberg, Frank M. (1992) "Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment FRANK M. LOEWENBERG Bar-Ilan University Israel School of Social Work The American model of the welfare state, incomplete as it may be, was not plucked out of thin air by the architects of the New Deal in the 1930s. Instead it is the product and logical evolution of a long histori- cal process. 19th century federal relief programsfor various population groups, including veterans, native Americans, merchant sailors, eman- cipated slaves, and residents of the District of Columbia, are examined in order to help better understand contemporary welfare developments. Many have argued that the federal government was not in- volved in social welfare matters prior to the 1930s - aside from two or three exceptions, such as the establishment of the Freed- man's Bureau in the years after the Civil War and the passage of various federal immigration laws that attempted to stem the flood of immigrants in the 1880s and 1890s. -

The History of Dunedin Income Growth Investment Trust

The History of Dunedin Income Growth Investment Trust PLC The first investment trust launched in Scotland, 1873 – 2018 Dunedin Income Growth Trust Investment Income Dunedin Foreword 1873 – 2018 This booklet, written for us by John Newlands, It is a particular pleasure for me, as Chairman of DIGIT describes the history of Dunedin Income Growth and as former employee of Robert Fleming & Co to be Investment Trust PLC, from its formation in Dundee able to write a foreword to this history. It was Robert in February 1873 through to the present day. Fleming’s vision that established the trust. The history Launched as The Scottish American Investment Trust, of the trust and its role in making professional “DIGIT”, as the Company is often known, was the first investment accessible is as relevant today as it investment trust formed in Scotland and has been was in the 1870s when the original prospectus was operating continuously for the last 145 years. published. I hope you will find this story of Scottish enterprise, endeavour and vision, and of investment Notwithstanding the Company’s long life, and the way over the past 145 years interesting and informative. in which it has evolved over the decades, the same The Board of DIGIT today are delighted that the ethos of investing in a diversified portfolio of high trust’s history has been told as we approach the quality income-producing securities has prevailed 150th anniversary of the trust’s formation. since the first day. Today, while DIGIT invests predominantly in UK listed companies, we, its board and managers, maintain a keen global perspective, given that a significant proportion of the Company’s revenues are generated from outside of the UK and that many of the companies in which we invest have very little exposure to the domestic economy. -

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19Ctheatrevisuality

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19ctheatrevisuality Henry Emden, City of Coral scene, Drury Lane, pantomime set model, 1903 © V&A Conference at the University of Warwick 27—29 June 2019 Organised as part of the AHRC project, Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, Jim Davis, Kate Holmes, Kate Newey, Patricia Smyth Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century Funded by the AHRC, this collaborative research project examines theatre spectacle and spectatorship in the nineteenth century by considering it in relation to the emergence of a wider trans-medial popular visual culture in this period. Responding to audience demand, theatres used sophisticated, innovative technologies to create a range of spectacular effects, from convincing evocations of real places to visions of the fantastical and the supernatural. The project looks at theatrical spectacle in relation to a more general explosion of imagery in this period, which included not only ‘high’ art such as painting, but also new forms such as the illustrated press and optical entertainments like panoramas, dioramas, and magic lantern shows. The range and popularity of these new forms attests to the centrality of visuality in this period. Indeed, scholars have argued that the nineteenth century witnessed a widespread transformation of conceptions of vision and subjectivity. The project draws on these debates to consider how far a popular, commercial form like spectacular theatre can be seen as a site of experimentation and as a crucible for an emergent mode of modern spectatorship. This project brings together Jim Davis and Patricia Smyth from the University of Warwick and Kate Newey and Kate Holmes from the University of Exeter. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

Perishable Shipment Tracker: Using Iot, Web Bluetooth and Blockchain to Raise Accountability and Lower Costs in the Perishable Shipment Process

Perishable Shipment Tracker: Using IoT, Web Bluetooth and Blockchain to Raise Accountability and Lower Costs in the Perishable Shipment Process The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Galibert, Roland. 2019. Perishable Shipment Tracker: Using IoT, Web Bluetooth and Blockchain to Raise Accountability and Lower Costs in the Perishable Shipment Process. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37364573 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Using Espruino, Blockchain and Amazon Web Services to Raise Accountability and Lower Costs in Perishable Shipping Roland L. Galibert A Thesis in the Field of Software Engineering for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2019 © 2019 Roland L. Galibert Abstract Just like many other fields of application, IoT and blockchain have not left the perishable shipment industry untouched, and these technologies have already improved the overall quality of perishable goods by bringing advances to the shipping process. However, there is still a great deal of room for improvement, especially with regard to making IoT sensors more cost-effective, improving the accuracy of IoT sensors, and raising -

The Political History of Nineteenth Century Portugal1

The Political History of Nineteenth Century Portugal1 Paulo Jorge Fernandes Autónoma University of Lisbon [email protected] Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses National University of Ireland [email protected] Manuel Baiôa CIDEHUS-University of Évora [email protected] Abstract The political history of nineteenth-century Portugal was, for a long time, a neglected subject. Under Salazar's New State it was passed over in favour of earlier periods from which that nationalist regime sought to draw inspiration; subsequent historians preferred to concentrate on social and economic developments to the detriment of the difficult evolution of Portuguese liberalism. This picture is changing, thanks to an awakening of interest in both contemporary topics and political history (although there is no consensus when it comes to defining political history). The aim of this article is to summarise these recent developments in Portuguese historiography for the benefit of an English-language audience. Keywords Nineteenth Century, History, Bibliography, Constitutionalism, Historiography, Liberalism, Political History, Portugal Politics has finally begun to carve out a privileged space at the heart of Portuguese historiography. This ‘invasion’ is a recent phenomenon and can be explained by the gradual acceptance, over the course of two decades, of political history as a genuine specialisation in Portuguese academic circles. This process of scientific and pedagogical renewal has seen a clear focus also on the nineteenth century. Young researchers concentrate their efforts in this field, and publishers are more interested in this kind of works than before. In Portugal, the interest in the 19th century is a reaction against decades of ignorance. Until April 1974, ideological reasons dictated the absence of contemporary history from the secondary school classroom, and even from the university curriculum. -

La Crème De La Crème

W E L C O M E T O T H E H O C K E N Friends of the Hocken Collections B U L L E T I N NU M B E R 26 : November 1998 La Crème de la Crème THE MOVE of the Hocken Library, reconsolidated with Hocken Archives, into the old Otago Co-operative Dairy Company building on Anzac Avenue, is an opportune time to examine some of the material on the dairy industry held within the Hocken collections. While the NZ dairy industry is now more often associated with Taranaki and the Wai- kato, Otago has a special place in the history of that industry. The first co-operative dairy factory in New Zealand was located on the Otago Peninsula, and the country’s first refrigerated butter export sailed on the s.s.Dunedin from Port Chalmers in 1882. Both were seminal events for the industry that was to become one of New Zealand’s most important export earners. The first moves away from simple domestic production of butter and cheese towards a more commercial operation in New Zealand were probably made either on Banks Peninsula or in Taranaki in the 1850s. In 1855, some five tons of butter and 34 tons of cheese were exported from Banks Peninsula to the rest of New Zealand and Australia, while at some time during the decade a ‘factory’ was established in Taranaki to collect milk from several suppliers to produce cheese for local sale. However, the birth of the co-operative system which came to typify the New Zealand dairy industry took place in Otago. -

1790S 1810S 1820S 1830S 1860S 1870S 1880S 1950S 2000S

Robert Fulton (1765-1815) proposes plans for steam-powered vessels to the 1790s U.S. Government. The first commercial steamboat completes its inaugural journey in 1807 in New York state. Henry Shreve (1785-1851) creates two new types of steamboats: the side-wheeler and the 1810s stern-wheeler. These boats are well suited for the shallow, fast-moving rivers in Arkansas. The first steamboat to arrive in Arkansas, March 31, 1820 Comet, docks at the Arkansas Post. Steamboats traveled the Arkansas, Black, Mississippi, Ouachita, and White Rivers, carrying passengers, raw 1820s materials, consumer goods, and mail to formerly difficult-to-reach communities. Steamboats, or steamers, were used during From the earliest days of the 19th Indian Removal in the1830s for both the shipment 1830s of supplies and passage of emigrants along the century, steamboats played a vital role Arkansas, White, and Ouachita waterways. in the history of Arkansas. Prior to the advent of steamboats, Arkansans were at the mercy of poor roads, high carriage Quatie, wife of Cherokee Chief John Ross, dies aboard Victoria on its way to Indian costs, slow journeys, and isolation. February 1, 1839 Territory and is buried in Little Rock Water routes were the preferred means of travel due to faster travel times and During the Civil War, Arkansas’s rivers offered the only reliable avenue upon which either Confederate or Union fewer hardships. While water travel was 1860s forces could move. Union forces early established control preferable to overland travel, it did not over the rivers in Arkansas. In addition to transporting supplies, some steamers were fitted with armor and come without dangers. -

WILLIAM SOLTAU DAVIDSON (1846-1924) Pioneer of the Frozen Meat Industry in New Zealand

WILLIAM SOLTAU DAVIDSON (1846-1924) Pioneer of the Frozen Meat Industry in New Zealand The economic success of New Zealand in the second half of the 19th century was due in no small part to the endeavours of this man. Along with Thomas Brydone he pioneered the frozen meat export trade that was to become the backbone of New Zealand's export economy. Although born in Canada, he came from a family that had its roots in Scottish banking and commence. His father David Davidson had been the Edinburgh manager of the Bank of Scotland. William was educated at the Edinburgh Academy in preparation for a commercial career, but he was essentially a man of action who did not want a life behind a desk. In 1865 he took a cadetship in the Canterbury and Otago Association, a Scottish pastoral association. He arrived at Port Chalmers on 30 December 1865 on the sailing ship Calaeno before travelling to Timaru to work on the famous Levels Estate. At this time this was a vast establishment of more than 150,000 acres extending into the South Island high country. Most of the estate staff were fellow Scots. Over the next ten years, William learned and became skilled at the many and varied tasks required of a station manager and in 1875 became the Association's inspector. By this time the Association's holdings had grown to over 500,000 acres. William was heavily involved in the freeholding of much of this land. A series of amalgamations of land companies including the original Canterbury and Otago Association had led to the establishment of the New Zealand and Australian Land Company which had a total land holding in both countries of three million acres by the mid 1870s. -

The Kinney Gang in 1873, 25-Year Old John Kinney Mustered out of the U.S

This is a short biography of outlaw John Kinney, submitted to SCHS by descendant Troy Kelly of Johnson City, NY. John W. Kinney was born in Hampshire, Massachusetts in 1847 (other sources say 1848 or 1853). He and his family moved to Iowas shortly after John was born. On April 13, 1867, Kinney enlisted in the U.S. Army at Chicago, Illinois. On April 13, 1873, at the rank of sergeant, Kinney was mustered out of the U.S. Army at Fort McPherson, Nebraska. Kinney chose not to stay around Nebraska, and he went south to New Mexico Territory. Kinney took up residence in Dona Ana County. He soon became a rustler and the leader of a gang of about thirty rustlers, killers, and thieves. By 1875, the John Kinney Gang was the most feared band of rustler in the territory. They rustled cattle, horses, and mules throughout New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and Mexico. However, the headquarters for the gang was around the towns of La Mesilla and Las Cruces, both of them located in Dona Ana County. Kinney himself was a very dangerous gunslinger. His apprentice in the gang was Jessie Evants. On New Year's Even in 1875, Kinney, Jessie Evans, and two other John Kinney Gang members name Jim McDaniels and Pony Diehl, got into a bar-room brawl in Las Cruces with some soldiers from nearby Fort Seldon [sic]. The soldiers beat the four rusterls in the fight, and the outlaws were tossed out of the establishment. Kinney himself was severely injured during the fight. Later that night, Kinney, Evans, McDaniels, and Diehl took to the street of Las Cruces and went in front of the saloon they had recently been tossed out of. -

BROTHERS OR ENEMIES the Ukrainian National Movement And

BROTHERS OR ENEMIES The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s “Moskal.” Mykola Hatchuk, Ukrainska abetka. Moscow: Universytetska dru- karnia, 1861. Courtesy of the National Library of Finland, Slavic collection. JOHANNES REMY Brothers or Enemies The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2016 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4875-0046-7 ♾ Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. _________________________________________________________________ Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Remy, Johannes, 1962–, author Brothers or enemies : the Ukrainian national movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s / Johannes Remy. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4875-0046-7 (cloth) 1. Nationalism – Ukraine – History − 19th century. 2. Ukrainian literature – Censorship – History − 19th century. 3. Imperialism − History − 19th century. 4. Ukraine – History − 19th century. 5. Ukraine − Politics and government − 19th century. 6. Ukraine – Relations − Russia – History − 19th century. 7. Russia – Relations – Ukraine − History − 19th century. I. Title. DK508.772.R44 2016 947.708 C2016-904895-0 _________________________________________________________________ This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publica- tions Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The Kowalsky Program for the Study of Eastern Ukraine at Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies has assisted the publication of this book. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario. -

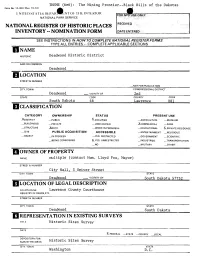

Iowner of Property

THEME (6e6): The Mining Frontier Black Hills of the Dakotas Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^^ UNITED STATES DHPARwIiNT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Deadwood Historic District AND/OR COMMON Deadwood LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Deadwood _ VICINITY OF 2nd STATE CODE COUNTY CODE South Dakota 46 Lawrence 081 Q CLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -X.COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT ._IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED X_YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME multiple (contact Hon. Lloyd Fox, Mayor) STREEF& NUMBER City Hall, 5 Seiver Street CITY, TOWN STATE Deadwood VICINITY OF South Dakota 57732 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Lawrence County Courthouse REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Deadwood South Dakota I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE ^.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORYSURVEY RECORDS FOR HistoricTT . Sites-, . Survey„ CITY, TOWN STATF. Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED MOVED DATF _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Deadwood was a boom town created in 1875 during the Black Hills gold rush. The district is situated in the central area of the town of Deadwood and lies in a steep and narrow valley.