Urgency of Mapping up the Punjab Borderlines and Partition Violence and Mass Migrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Wise Demand of Ctis of Gujranwala Division No

College Wise Demand of CTIs of Gujranwala Division No. of No. of Total No. of CTIs required Subject Sr. CMIS teachers students in the Subject Name of the College Division District in which CTI already No Code in the Minority Disable is required Working in Open Total Subject 5% 3% Subject Govt. P/G College (Boys), Sateelite Town, 1 341101 Gujranwala Gujranwala Commerce 0 528 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala. Computer 2 341102 Govt. Degree College (B) Qila Didar Singh Gujranwala Gujranwala 0 91 1 0 0 1 Science 3 341103 Govt. Postgraduate Islamia College Gujranwala Gujranwala Gujranwala Botany 0 100 1 0 0 1 Govt. FMF Post Graduate College Peoples Colony, Health & 4 341104 Gujranwala Gujranwala 0 134 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala Physical Govt. Post Graduate College (W) Model Town ComputerEducation 5 341106 Gujranwala Gujranwala 0 386 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala Science Govt. Post Graduate College (W) Model Town Pakistan 6 341106 Gujranwala Gujranwala 0 1050 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala Study Govt. Post Graduate College (W) Model Town 7 341106 Gujranwala Gujranwala Open 0 0 0 0 1 1 Gujranwala Govt. Post Graduate College (W) Model Town 8 341106 Gujranwala Gujranwala Fine Arts 0 95 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala Govt. Post Graduate College (W) Model Town Home 9 341106 Gujranwala Gujranwala 0 120 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala Economics Govt. Post Graduate College (W) Model Town 10 341106 Gujranwala Gujranwala Persian 0 350 1 0 0 1 Gujranwala Computer 11 341107 Govt. College For Women, Gujranwala City Gujranwala Gujranwala 0 425 1 0 0 1 Science 12 341107 Govt. -

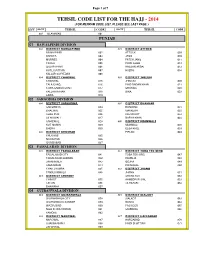

Tehsil Code List for the Hajj

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ - 2014 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Village List of Gujranwala , Pakistan

Census 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-18 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST I PUNJAB Lahore Divisiona .,.(...t..G.ElCY- OF THE PROVINCIAL TEN DENT CENSUS, JUr.8 1952 ,NO BAHAY'(ALPUR Prleo Ps. 6·8-0 FOREWORD This Village List has been pr,epared from the material collected in con" nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be avaflable and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showing its area to the nearest square mile. and Its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsil the Revenue Kanungo holqos are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo holqa and the remaining Villages comprising the ha/qas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column o. Rokhs (tree plantations) and other similar areas even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast numbers have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries. -

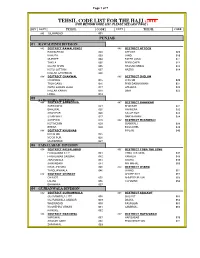

Tehsil Code List 2014

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ -2016 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface Bureau of Statistics has been issuing this publication since 1972. The present edition is the 43rd in the series. It provides important statistics in respect of social, economic and financial sectors of the economy at aggregate as well as sectoral levels. This publication contains data on almost all sectors of the Provincial economy with their break-up by Tehsil, District & Division as far as possible. Eight tables on Monthly Electricity and Gas Consumption, Number of Zoo, Number of Bulldozers, Small and Mini Dams, Recognized Slaughter Houses and two provisional tables on population census 2017 are also added in this issue. It includes some national data on important subjects like Major Crops, Foreign Trade, Labour Force & Employment, National Accounts, Population, Price and Transport etc. It contains a 'Statistical Abstract' which gives a comparative picture of information on almost all Socio- Economic sectors of Pakistan and the Punjab. Key findings of Multiple Indicator Cluster Servey (MICS): 2014 of some of the Socio-Economic Indicators are also included in this edition viz-a-viz Education, Health, Housing and Socio-Economic Development by district. Every effort has been made to include the latest available data in this publication. It is hoped that this publication will be useful to the policy makers, planners, researchers, govt. departments and other users of Socio-Economic data in public as well as private sector. I am thankful to various Provincial Departments / Agencies / Federal Ministries / Divisional/District offices for supplying the required data. Without their co-operation, it would have not been possible to release this publication in time. -

Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis C Virus Genotypes in Different Geographical Regions of Punjab Province in Pakistan and A

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector International Journal of Infectious Diseases 17 (2013) e247–e253 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis C virus genotypes in different geographical regions of Punjab Province in Pakistan and a phylogenetic analysis a, a a b a a c Hafsa Aziz *, Abida Raza , Shahnaz Murtaza , Yasir Waheed , Ali Khalid , Javaid Irfan , Zahoor Samra , c Muhammad Amin Athar a Diagnostic Laboratories, Nuclear Medicine Oncology and Radiotherapy Institute, Hanna Road, G-8/3, Islamabad, Pakistan b NUST Center of Virology and Immunology, National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan c Institute of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan A R T I C L E I N F O S U M M A R Y Article history: Background: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a causative agent of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and Received 11 April 2012 hepatocellular carcinoma. In Pakistan, more than 10 million people are living with HCV. Very little is Received in revised form 29 August 2012 known about the genotype distribution in Punjab Province, the largest province of Pakistan. Accepted 26 September 2012 Pretreatment genotype identification is very important, as different HCV genotypes respond differently Corresponding Editor: Mark Holodniy, to interferon therapy. California, USA Methods: In this study we performed HCV genotyping for 1537 HCV-infected patients from different districts of Punjab Province, Pakistan. Sequencing of partial HCV NS5B sequences from 14 samples Keywords: belonging to genotypes 3 and 1 was also done. -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs. -

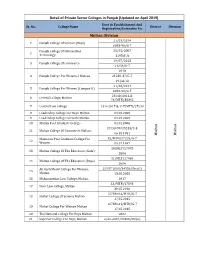

Detail of Private Sector Colleges in Punjab (Updated on April 2019) Date of Establishment and Sr

Detail of Private Sector Colleges in Punjab (Updated on April 2019) Date Of Establishment And Sr. No. College Name District Division Registration/Extension No. Multan Division 21/03/2014 1 Punjab College Of Science (Boys) 6083-90/G-7 Punjab College Of Information 25/05/2007 2 Technology 1193/P.A 29/07/2013 3 Punjab College Of Commerce 21238/G-7 2013 4 Punjab College For Women-I Multan 21230-37/G-7 29-Jul-13 21/03/2014 5 Punjab College For Women (Campus-Ii) 6092-99/G-7 28/10/2016 & 6 Central College, Multan 76/MTN/38342 7 Central Law College 13-9-2017 & 117/MTN/27249 8 Leadership College For Boys Multan. 01.05.2005 9 Leadership College For Girls Multan. 01.05.2005 10 Multan Post Graduate College 01.01.2006 27/53-90/29213/C-3 11 Multan College Of Commerce, Multan. 06.10.1991 Multan Multan Mamoona Post Graduate College For 82/MTN/27225/G-7 12 Women 01.07.1997 10/MLT/27978 13 Multan College Of The Educators (Girls) 2004 11/MLT/27969 14 Multan College Of The Educators (Boys) 2004 Ali Garh Model College For Women, 2/137-2008/34336/Dir.(G) 15 Multan. 13.08.2008 16 Mohammedan Law College, Multan. 2017 13/MTN/17845 17 Noor Law College, Multan 30.05.2016 1273No14/MTN/G-7 18 Nishat College Of Science Multan 17.05.2015 1273No14/MTN/G-7 19 Nishat College For Women Multan 17.05.2015 20 The National College For Boys Multan 2002 21 Superior College For Boys, Multan 2/42-2007/37488/Dir(G) 22 Superior College For Girls, Multan 2/43-2007/37495/Dir(G) International Degree College Of RP/2287 DATED 18-06-1986 23 Commerce Multan. -

Chief Election Commissioner

CHIEF ELECTION COMMISSIONER AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR ELECTION COMMISSION SECRETARIAT BLOCK NO.6 (LOWER GROUND)NEW SECRETARIAT COMPLEX CHATTER DELIMITATION COMMISSION AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR MIRPUR DISTRICT S. No. Number and name of Extent of the Constituency Constituency 1. LA-I, MIRPUR – I. The Whole Tehsil of Dadyal 2. LA-II, MIRPUR – II. The following Patwar Circles of Mirpur Tehsil:- 1. Palak 2. Pind Khurd 3. Dheri Phali 4. Dheri Barwan. 5. Chakswari 6. Panyam 7. Boa 8. Tang Dew 9. Kaneli. 10. Mawah 11. Bajjar 12. Herdochi 13. Islam Garh. 14. Kalyal Bainsi 15. Potha Bainsi. 3. LA-III, MIRPUR – III. The following Patwar Circles of Mirpur Tehsil:- 1. Khanpur 2. Kharak 3. Rathoa Muhammad Ali. 4. Thothal 5. Sangot 6. Mirpur Muncipal area. 4. LA-IV, MIRPUR – IV. The following Patwar Circles of Mirpur Tehsil:- 1. Khari Khas 2. Aziz Pur 3. Lehri 4. Sonkia. 5. Bhalyala 6. Khurd 7. Pindi-Suberwal 8. Afzal Pur. 9. Samwal shrif 10. Pulmanda 11. Sahang 12. Bani. 13. Balwara 14. Jatlan 15. Jouian 16. Janian. 17. Pakharal 18. Naugran 19. Dhalmahmood 20. Raipur. BHIMBER DISTRICT 5. LA-V, BHIMBER – I. The Whole Tehsil of Barnala. 6. LA-VI, BHIMBER – II. The Whole Tehsil of Samahni. 7. LA-VII, BHIMBER – III. The Whole Tehsil of Bhimber. KOTLI DISTRICT 8. LA-VIII, KOTLI – I. The following Patwar Circles of Kotli Tehsil:- 1. Kotli Khas 2. Roli 3. Dhanwan 4. Goi 5.Kakanni Baghah. 6. Phagwari 7.Dhamol 8.Gulhar Shrif 9.ChowkiTeenda 10. Jhanjora 11.Dundli. 9. LA-IX, KOTLI – II. (i) The Whole Tehsil of Fatehpur (Nakyal). -

List of Agro Based Industry in the District Lahore

LIST OF AGRO BASED INDUSTRY IN THE DISTRICT LAHORE Sr. Agro Based Complete Address Fax No./ E-mail Phone No./Mobile Name of Factory/Mill Website No. Industry (Tehsil/District) Address No. supremfloor@supreem 1 Supreme flour Mill 22 Km Multan Road Lahore - 04235979103-4 .com.pk 042-37417541, 2 Ferdous flour Mill Band Road Bakar Mandi Lahore - - 042-37417535 Ghulamhussain0009@ 0323-9000349, 3 Good Luck flour Mill Defiance Road Mohnal wal Lahore - gmail.com 0323-900689 4 Sajid flour Mill Defiance Road Mohnal wal Lahore - - 0333-4785186 yaqomiafloorMill@gmai 0300-4104232, 5 Yaqomia flour Mill Pool LubanaMultan Road Lahore - l.com 04237511216-17-18 6 zimidaar flour Mill Sundar Indusial Sundar Raiwind - - 0300-8445300 Sundar Indusial Sundar Raiwind 0321-4855526, 7 Arabia flour Mill - - Road Lahore 042-35063394 8 Farman flour Mill Sham Ky Bhattia Multan road Lahore - - 0321-4203006 18Km Multan Road Near Shabab 9 Hajvery flour Mill - - 3238117777 Stoudo Block No.394 Sundar Indusial State abullahfloorMill@yahoo 0300-8499467, 10 Flour Mills Abdullah flour Mill - Sundar Raiwind Road .com 04235298519 Sundar Indusial State Sundar 11 Bahoo flour Mill - - 0308-6666888 Raiwind Road Block No.37 Sundar Indusial State 0321-7777466, 12 Al-Muhktar flour Mill www.mukhtar.pk - Sundar Raiwind Road 0300-8465151 Sundar Indusial State Sundar 13 Taaj flour Mill - - 0301-6577037 Raiwind Road Lahore Mouza sultan kay Sundar Raiwind 14 Ajwa flour Mill - - 0300-6561208 Road lahore Malik M.Rafoq S/o Abdul Aziz 15 Malik flour Mill - - 0320-3414121 Sundar Raiwind Road Lahore 16 Number Daar flour Mill - - 0333-4508002 17 Raiwind Flour Mills Sunder Road Raiwind Dist Lahore - - 042-5390998 18 Behria Flour Mills Lahore Road Raiwind Dist Lahore - - 0300-8482012 19 G.L Flour Mills Lahore Road Raiwind Dist Lahore - - 0303-4563077 Sr. -

17Th Sep, 2014

Daily Emergency and Response Situational Information Report –17th Sep, 2014 17th Sep i Daily Emergency and Response Situational Information Report –17th Sep, 2014 NOTE - iMMAP compiles these reports from the specified data sources and endeavors to get the most up-to-date and accurate figures available. iMMAP and USAID do not take any ownership or responsibility of the data accuracy in this report. Abbreviations AJK Azad Jammu and Kashmir AWD Acute Watery Diarrhea ARI Acute Respiratory infections BD Bloody Diarrhea CDCP Citizen’s Damage Compensation Programme CMAM Community Management of Acute Malnutrition CVH Chronic Viral Hepatitis CL Cutaneous Leishmaniasis EPI Expanded Programme for Immunization FDMA Fata Disaster Management Authority FSC Food Security Cluster FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FFW Food For Work FFT Food For Training GFD General Food Distribution GB Gilgit Baltistan IDP Internally Displaced Persons IOM International Organization for Migration KPK Khyber Pakhtunkhwa MUAC Mid - Upper Arm Circumference MAL Confirmed Malaria MAM Moderate Acute Malnutrition NFIs Non-Food Items NWA North Waziristan Agency NSC Nutrition Stabilization Centers OAD Other Acute Diarrhea OTH Other diseases PDMA Provincial Disaster Management Authority PRCS Pakistan Red Crescent Society PS Protection Services PLC Protective Learning and Center PN Pneumonia PUO Pyrexia Unknown Origin UC Union Council UNFPA United Nations Population Fund Agency CSOs Civil Society Organizations PV Plasmodium Vivax PF Plasmodium Falciparum Conversion 1 MT = 1,000 -

An Analysis of Development Budget of the Punjab, 2018-19

Geographic Spread of Resources: An Analysis of Development Budget of the Punjab, 2018-19 Geographic Spread of Resources: An Analysis of Development Budget of the Punjab, 2018-19 Table of Contents Geographic Spread of Resources: .......................................................................................................... 1 An Analysis of Development Budget of the Punjab, 2018-19 ................................................................ 1 Geographic Spread of Resources: An Analysis of Development Budget of the Punjab, 2018-19 ......... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Rationale of this Study ....................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Background ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Revenue Development Budget ........................................................................................................... 6 Revenue Development Budget-District Wise ..................................................................................