Migration and Borders in Coronation Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Career Development Module

Onwards & Upwards A Toolkit for Careers Advisors Working with Mature Students in Higher Education Onwards & Upwards A Toolkit for Careers Advisors Working with Mature Students in Higher Education Careers Service Cooperative Education & Careers Division University of Limerick www.ul.ie/careers Written by Patsy Ryan, Careers Advisor - University of Limerick April 2007 Onwards & Upwards Summary This toolkit serves as a framework for those working with adult learners who are planning to study at third level. It comprises two modules, Educational Guidance and Career Development, which highlight and examine the core aspects of educational and career preparation through a number of tutorials which include course and career investigation, grant applications, skills identification, CV and application form preparation, interview advice and overall self-awareness. Each tutorial comprises an introductory text and presentation slides, while others have assignments and additional materials to support tutorial activities. Both modules offer practical exercises, which enable students to relate to and customise the learning to meet their own needs. Students also gain the opportunity to give oral presentations and submit assignments and reports, activities that are typical of most educational and career paths today. The toolkit guides and advises tutors throughout all aspects of the modules, while allowing for flexibility in each tutorial given the diverse needs of all groups. Through regular feedback and updating, the toolkit continues as an invaluable aid in supporting adult learning. This report can be downloaded at: http://www.ul.ie/careers/careers/mature/toolkit.shtml. Summary Toolkit Overview iii Onwards & Upwards Acknowledgements Thanks to the students on the Mature Student Access Certificate Course at the University of Limerick who provided feedback on the modules for this toolkit and who were such a joy to work with. -

Collectors Club Special Price List

LEGEND PRODUCTS CLUB MEMBER'S ONLY 2003 Collector's Club Price List & Order Form Please tick any item and mail it to us MY CLUB MEMBER NO.IS Customer Name: Customer Address Order Date: Delivery Date Req The 'Roost' 1 garden Villas, Cefn Y Bedd, Wrexham LL12 9UT.UK TEL(44) (0)1978 760800 SPECIAL COLLECTORS CLUB PAINTINGS Description Price Each £ Qty. Ordered Description Qty .Ordered Price Each £ ARTFUL DODGER 19.00 CLEOPATRA BLACK/GOLD/ 19.00 FAGIN 19.00 POPE JOHN PAUL ALL GOLD 30.00 PICKWICK 19.00 WI. SHAKESPEARE GREEN/GOLD 19.00 SAIRY GAMP 19.00 THE COOK GREEN/WHITE 19.00 BILL SYKES 19.00 CHR'S. COLUMBAS white/gold 19.00 BUMBLES 19.00 GULF WAR VETERAN 19.00 CLOWN 1 19.00 CLOWN 2 19.00 CLOWN 3 19.00 CLUB SPECIAL MODELS 6" pieces CLOWN 4 19.00 ROBINSON CRUSOE 22.50 CLOWN 5 19.00 HUCK FINN 19.00 CLOWN 6 19.00 SEAFARER CRIMSON /GREY 19.00 CLOWN 7 19.00 DICK TURPIN 19.00 CLOWN 8 19.00 ROBERT BURNS BLACK /SILVER 19.00 LENA 19.00 80.00 LOUIS 19.00 American history BRIGAND 19.00 NAVAJO WITH WAR PAINT 19.00 BEDOUIN 19.00 CRAZY HORSE & WAR PAINT 19.00 AFGHAN 19.00 SITTING BULL & WAR PAINT 19.00 INDIAN PRINCE 19.00 WESTERNER BLUE &YELLOW 19.00 AHMED 19.00 SIKH 19.00 MEXICAN 19.00 Larger 7" & 8" pieces LIMITED EDITIONS MARK ANTHONY7" PURPLE/GOLD 22.50 No 105 JACK CARDS 26.00 THE JUDGE GREY/WHITE 8" 32.50 No 106 QUEEN CARDS 26.00 No 107 KING CARDS 26.00 BARBARY BUCCANEER (DOUBLE) 35.00 EASTERN HAWK (DOUBLE) 35.00 KING ARTHUR 29.00 ROMANY ROGUE (DOUBLE) 35.00 QUEEN GUINEVERE 29.00 THE INDIAN HORSEMAN (DOUBLE) 35.00 MERLIN THE MAGICIAN 29.00 LEGEND SPECIAL 250 80.00 ORONATION ST. -

Convenient Fictions

CONVENIENT FICTIONS: THE SCRIPT OF LESBIAN DESIRE IN THE POST-ELLEN ERA. A NEW ZEALAND PERSPECTIVE By Alison Julie Hopkins A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2009 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge those people who have supported me in my endeavour to complete this thesis. In particular, I would like to thank Dr Alison Laurie and Dr Lesley Hall, for their guidance and expertise, and Dr Tony Schirato for his insights, all of which were instrumental in the completion of my study. I would also like to express my gratitude to all of those people who participated in the research, in particular Mark Pope, facilitator of the ‘School’s Out’ programme, the staff at LAGANZ, and the staff at the photographic archive of The Alexander Turnbull Library. I would also like to acknowledge the support of The Chief Censor, Bill Hastings, and The Office of Film and Literature Classification, throughout this study. Finally, I would like to thank my most ardent supporters, Virginia, Darcy, and Mo. ii Abstract Little has been published about the ascending trajectory of lesbian characters in prime-time television texts. Rarer still are analyses of lesbian fictions on New Zealand television. This study offers a robust and critical interrogation of Sapphic expression found in the New Zealand television landscape. More specifically, this thesis analyses fictional lesbian representation found in New Zealand’s prime-time, free-to-air television environment. It argues that television’s script of lesbian desire is more about illusion than inclusion, and that lesbian representation is a misnomer, both qualitatively and quantitively. -

Report Title Here Month Here

Alcohol & Soaps Drinkaware Media Analysis September 2010 © 2010 Kantar Media 1 CONTENTS •Introduction 3 •Executive Summary 5 •Topline results 7 •Coronation Street 16 •Eastenders 23 •Emmerdale 30 •Hollyoaks 37 •Appendix 44 Please use hyperlinks to quickly navigate this document. © 2010 Kantar Media 2 INTRODUCTION •Kantar Media Precis was commissioned to conduct research to analyse the portrayal of alcohol and tea in the four top British soap operas aired on non-satellite television, Coronation Street, Eastenders, Emmerdale and Hollyoaks. The research objectives were as follows: •To explore the frequency of alcohol use on British soaps aired on non-satellite UK television •To investigate the positive and negative portrayal of alcohol •To explore the percentage of interactions that involve alcohol •To explore the percentage of each episode that involves alcohol •To assess how many characters drink over daily guidelines •To explore the relationship between alcohol and the characters who regularly/excessively consume alcohol •To look further into the link between the location of alcohol consumption and the consequences depicted •To identify and analyse the repercussions, if any, of excessive alcohol consumption shown •To explore the frequency of tea use on British soaps aired on non-satellite UK television •Six weeks of footage was collected for each programme from 26th July to 6th September 2010 and analysed for verbal and visual instances of alcohol and tea. •In total 21.5 hours was collected and analysed for Emmerdale, 15.5 hours for Coronation Street, 15.5 hours for Hollyoaks and 13 hours for Eastenders. © 2010 Kantar Media 3 INTRODUCTION cont. •A coding sheet was formulated in conjunction with Drinkaware before the footage was analysed which enabled us to track different types of beverages and their size (e.g. -

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Dr Kate McNicholas Smith, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Professor Imogen Tyler, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Abstract The last decade has witnessed a proliferation of lesbian representations in European and North American popular culture, particularly within television drama and broader celebrity culture. The abundance of ‘positive’ and ‘ordinary’ representations of lesbians is widely celebrated as signifying progress in queer struggles for social equality. Yet, as this article details, the terms of the visibility extended to lesbians within popular culture often affirms ideals of hetero-patriarchal, white femininity. Focusing on the visual and narrative registers within which lesbian romances are mediated within television drama, this article examines the emergence of what we describe as ‘the lesbian normal’. Tracking the ways in which the lesbian normal is anchored in a longer history of “the normal gay” (Warner 2000), it argues that the lesbian normal is indicative of the emergence of a broader post-feminist and post-queer popular culture, in which feminist and queer struggles are imagined as completed and belonging to the past. Post-queer popular culture is depoliticising in its effects, diminishing the critical potential of feminist and queer politics, and silencing the actually existing conditions of inequality, prejudice and stigma that continue to shape lesbian lives. Keywords: Lesbian, Television, Queer, Post-feminist, Romance, Soap-Opera Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Increasingly…. to have dignity gay people must be seen as normal (Michael Warner 2000, 52) I don't support gay marriage despite being a Conservative. -

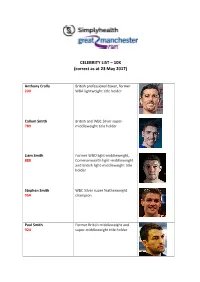

Correct As at 23 May 2017)

CELEBRITY LIST – 10K (correct as at 23 May 2017) Anthony Crolla British professional boxer, former 230 WBA lightweight title holder Callum Smith British and WBC Silver super- 789 middleweight title holder Liam Smith Former WBO light-middleweight, 888 Commonwealth light-middleweight and British light-middleweight title holder Stephen Smith WBC Silver super featherweight 954 champion Paul Smith Former British middleweight and 924 super-middleweight title holder Scott Quigg Former WBA super-bantamweight 410 super-bantamweight title holder Zelfa Barrett Undefeated British Super 567 Featherweight boxer Hosea Burton British light heavyweight champion 654 Marcus Morrison Former WBC International Silver 666 middleweight title Bryan Robson Former England and Man Utd 7 captain Sally Dynevor Sally Webster in Coronation Street, 27104 running for Beechwood Cancer Care Andy Burnham Recently elected Mayor of Greater 300 Manchester Carl Austin-Behan Outgoing Lord Mayor of Manchester 9805 Kym Marsh Michelle Connor in Coronation 500 Street Bruno Langley Todd Grimshaw in Coronation Street 550 Colson Smith Craig Tinker in Coronation Street 800 Joe Gill Finn Barton in Emmerdale 600 Andy Meyrick Professional British racing driver 750 Cherylee Houston Izzy Armstrong in Coronation Street 20520 Toby Hadoke Actor and stand-up comedian 18904 Denise Welch Actress and presenter 333 Lincoln Townley British contemporary artist 444 George Rainsford Ethan Hardy in Casualty 1008 Ray MacAllan Mr Selfridge, Casualty, The Haunting 1007 Sarah Anthony Actress 1003 Chelsea -

Lot 1368 1368

FROM LISMORTAGH STUD LOT 1368 1368 Gone West Elusive Pimpernel Elusive Quality Touch of Greatness (USA) Sadler's Wells BAY FILLY (IRE) Cara Fantasy Gay Fantasy May 17th, 2013 Norwich Top Ville Sally Webster (IRE) Dame Julian (1997) The Parson Emily Bishop Flying Pearl E.B.F. Nominated. This filly is unbroken. Sold with Veterinary Certificate. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam SALLY WEBSTER (IRE): 2 wins , £13,051: winner of a N.H. Flat Race at 4 years and placed twice; also winner over hurdles at 6 years and placed twice; dam of 2 runners and 6 foals; Sophie Webster (IRE) (2008 f. by Moscow Society (USA)): placed 3 times in point-to- points, 2015. Rosie Webster (IRE) (2010 f. by Turtle Island (IRE)): unraced to date. She also has a filly foal by Getaway (GER). 2nd dam EMILY BISHOP (IRE): unraced; dam of 2 winners from 9 runners and 10 foals inc.; Banellie (IRE): 2 wins over hurdles and £13,552 and placed 5 times. Catechist (IRE): 2 wins in point-to-points and placed once. Emily Rose (IRE): placed twice over hurdles; also winner of a point-to-point, broodmare. Grigori Rasputin (IRE): winner of a point-to-point. Wellpict One (IRE): placed twice in N.H. Flat Races; also placed once over hurdles. Hello Stranger (IRE): placed once in a point-to-point at 6 years. 3rd dam FLYING PEARL: unraced; dam of 2 runners and 5 foals: Emily Bishop (IRE): see above. 4th dam CHANTRY PEARL: ran a few times; dam of 3 winners from 6 runners and 10 foals; Jewelled Turban: 4 wins at 2 and 3 years and placed 6 times. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Episode 1 Confessions of a Gay Rugby Player What Goes on Tour Stay on Tour! by Robert India Улица Коронации

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Episode 1 Confessions of a Gay Rugby Player What Goes on Tour Stay on Tour! by Robert India Улица коронации. Carrying out Tony's bidding, Robbie leaves Carla bound and gagged while luring Hayley into his trap. Gail gives her account of Joe's final hours as her defence gets underway. David and Nick pin their. As Carla pleads for Hayley's release, Tony continues to douse Underworld in petrol. Maria flees to the Rovers and informs everyone about her ordeal. Roy desperately tries to gain access to the . Mike and Fred are joined by Tommy and Danny in a game of poker. Martin refuses to consider Katy's suggestion. Ken and Deirdre are put out by the arrival of Blanche's friend Wanda. Maria plans to . IMDb's Summer TV Roundup. We've rounded up our most anticipated new and returning TV shows you can't miss, all premiering in summer 2021. Related News. Maya Rudolph on Burnout, Beyoncé and the Magic Link Between Music and Comedy 05 May 2021 | Variety 5 Things We Learned From the New ‘Sesame Street’ Documentary 27 April 2021 | The Wrap Exclusive: Trailer arrives for British comedy ‘Me, Myself & Di’ 22 April 2021 | HeyUGuys. Salute to Asian and Pacific American Filmmakers. From The Way of the Dragon to Minari , we take a look back at the cinematic history of Asian/Pacific American filmmakers. Around The Web. Provided by Taboola. Editorial Lists. Related lists from IMDb editors. User Lists. Related lists from IMDb users. Share this Rating. Title: Улица коронации (1960– ) Want to share IMDb's rating on your own site? Use the HTML below. -

REUNITED! LEARNS 7-DAY Can Charity the TRAGIC Love Her Son? TRUTH TVGUIDE!

PADDY WITH REUNITED! LEARNS 7-DAY Can Charity THE TRAGIC love her son? TRUTH TVGUIDE! Liz & TORN Johnny APART! Toyah esses Bethany KIDNAP TERROR! KIM’S 23 us! AGONY! SARAH’S MICK’S BODY DEVASTATING SHOCKING FOUND! DIAGNOSIS! DISCOVERY! 9 770966 849166 Issue 23 • 9 - 15 June 2018 Elsewhere, we have even more of them soap stars. We Yo u r s t a r s have a lovely chinwag with ell, that was Windass to finish off the EastEnders’ Kim herself, this week! quite a ride super-villain. I loved the Tameka Empson (and she is in Corrie way the story came full- a lady who loves a chinwag!) 4 lastt week, wasn’t it? circle – with Anna, his first – as well as a chat with her Buut through the former on-screen love maany shocks interest Charles Venn, (and shots, “That was quite about Jacob’s sizzling ass Phelan a ride in Corrie!” encounter with Sam in wentw a bit Casualty. Plus, Street trrigger-happy!), victim in the Street, being actor Richard Hawley mym favourite bit the one to do the deed. (hasn’t he been amazing – which caused We catch up with Debbie recently?) gives us his mem to let out a Rush (who plays Anna) take on Johnny’s trouble Georgia big cheer – was on p14, where she tells all Steven Murphy, Editor [email protected] Taylor thhe return of Anna on her triumpant return. “The fallout of Toyah’s lies is catastrophic!” The BIG 22 10 stories... Coronation Street I’ll miss this place 4 Toyah’s baby bombshell! – but I feel I’ll carry part of it witthme 16 Liz offers a shoulder to cry on always.... -

OCTOBER 2010 Issue 144

SOUTH EDITION - OCTOBER 2010 Issue 144 October 2010 www.thetraderonline.es • Tel 902733622 1 IInlandnland & CCoastaloastal FFREEREE / GGRATISRATIS rader Authorised Dealer CCombinedombined rreadershipeadership ooff ooverver 335OOO5OOO Tel 902733633 T wwww.thetraderonline.es w w . t h e t r a d e r o n l i n e . e s SSOUTHOUTH EDITIONEDITION OCTOBEROCTOBER 22010010 Train Travel with Paul Little... ¨London to Spain in a Spanish Property with Mark Paddon Surveyor...‘man day is possible. It has cost me a little over £100 and been on the ground’ assessment for the end of 2010, based on fun to do. p.10 real sales and real buyer /vendor trends. p.16 Criminal Code Valencian reform could government Reduce jail terms REFORMS to Spain’s Criminal Code is likely to see around 3,000 prison sentences re- to freeze viewed in the Valencia region alone. AAshsh ccloudloud ccostsosts ValenciaValencia airportairport The new law, which comes into effect on taxes in 2011 December 23, will see maximum and mini- a quarterquarter ofof a millionmillion euroseuros THE Valencian regional government has an- mum sentences altered for certain offences nounced it will freeze taxes in 2011, which including drug-traffi cking, property corrup- will mean savings of 48 million euros for the tion cases, selling pirate goods, and crimes VALENCIA airport suffered 29,700 passengers due to on a fl ight after airline au- general public. relating to road safety. losses reaching nearly a fl y to and from the Manises thorities declared the atmos- Income tax rebates of the past two years Where the reformed Criminal Code means quarter of a million euros terminal were stranded or phere safe for fl ying. -

Westminsterresearch Lesbian Brides

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Lesbian brides: post-queer popular culture McNicholas Smith, K. and Tyler, I. This is an accepted manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Feminist Media Studies, 17 (3), pp. 315-331. The final definitive version is available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1282883 © 2017 Taylor & Francis The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Dr Kate McNicholas Smith, Lancaster University Professor Imogen Tyler, Lancaster University Abstract The last decade has witnessed a proliferation of lesbian representations in European and North American popular culture, particularly within television drama and broader celebrity culture. The abundance of ‘positive’ and ‘ordinary’ representations of lesbians is widely celebrated as signifying progress in queer struggles for social equality. Yet, as this article details, the terms of the visibility extended to lesbians within popular culture often affirms ideals of hetero-patriarchal, white femininity. Focusing on the visual and narrative registers within which lesbian romances are mediated within television drama, this article examines the emergence of what we describe as ‘the lesbian normal’. Tracking the ways in which the lesbian normal is anchored in a longer history of “the normal gay” (Warner 2000), it argues that the lesbian normal is indicative of the emergence of a broader post-feminist and post-queer popular culture, in which feminist and queer struggles are imagined as completed and belonging to the past. -

Kym Marsh Tells OK!’S Annabel Zammit She’S Looking Forward to the Next Phase in Her Life As She Celebrates Her Milestone Birthday with Her Son David

The birTHDAy girL invites us to her pARTY ‘LIFe rEAlly dOEs BEGIn at 40 – I’M In a gREAt pLACE’ ‘Coronation street’ star kym marsh teLLs OK!’s annabeL zammit she’s Looking forward to the next phase in her Life as she CELebrates her miLestone birthday with her son DAVID tilt walkers, magicians and a jazz band greeted 250 guests on a sunny Manchester evening as they arrived at a Sparty to celebrate Kym Marsh’s 40th birthday and her son David’s 21st. The actress’s Coronation Street co-stars – including Simon Gregson, Antony Cotton, Mikey North, Daniel Brocklebank and Sair Khan – were among those in attendance at the bash at private members’ lounge On The 7th, which is a stone’s throw from the Corrie studio in Manchester’s Media City. The lavish venue, which was decorated with gold, silver and white balloons, also had a cinema and play room for guests’ younger children and several games rooms for adults, including a graffiti room and a beer pong room, where Real Housewives Of Cheshire star and Kym’s close friend Dawn Ward could later be found alongside Kym taking up the challenge with fellow guests! A happy Kym, who looked stunning in a black prom dress by Forever Unique, told OK! she had no qualms about turning 40. ‘I’ve got a really good idea of what my life looks like for the foreseeable future and I think that’s comforting. I’m happy with work and I’m comfortable and happy in my personal life too.