The Alchemical Apocalypse of Isaac Newton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Relations of Salary to Title in American Universities Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9q2nf7df No online items Guide to the Relations of Salary to Title in American Universities Collection Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Relations of Salary SC0800 1 to Title in American Universities Collection Overview Call Number: SC0800 Creator: Stillman, John Maxson, 1852-1923. Title: Relations of salary to title in American universities collection Dates: 1906-1907 Physical Description: 0.5 Linear feet Summary: Stanford president David Starr Jordan issued a circular letter in October 1906 to college presidents and faculty on the issue "should the same salary be paid to men bearing the same title." Included in this collection are the letters received and John Maxson Stillman's resulting article, in typescript form and as published in SCIENCE (February 15, 1907). The majority of the letters are from faculty at Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley; other colleges represented include Cornell, University of Chicago, Harvard, University of Michigan, and University of Wisconsin. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Information about Access This collection is open for research. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

Splend S Lis R

Splend r SOlis Travesera de Gracia, 17-21 Tel. UK +44 (0)20 7193 4986 Tel. Spain +34 93 240 20 91 08021 Barcelona - Spain Tel. USA +1 305 831 4986 www.moleiro.com The Splendor Solis is the most beautiful treatise on alchemy ever made. Splendor Solis The British Library • London «First, unique and unrepeatable edition strictly limited to 987 copies» This codex, dated 1582, is the most • Shelf mark: Suppl. turc 242. beautiful treatise on alchemy ever • Date: 1582. made. The imagination and lyri- • Size: 230 x 330 mm. cism of its truly marvellous illus- • 100 pages, 22 full-page illuminations. trations are awe-inspiring even to lavishly embellished with gold. those not familiar with this subject. • Bound in crimson leather decorated The secrets of kabbalah, astrology with gold. and alchemic symbolism are revea- • Full-colour commentary volume (448 p.) led on 22 folios bearing full-page by Thomas Hofmeier (Historian of illustrations with a wealth of colo- Alchemy) Jörg Völlnagel (Art historian, ur and almost Baroque profusion research associate at the Staatliche of detail. Museen zu Berlin), Peter Kidd (Former curator of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at the Bodleian and British Libraries) and Joscelyn Godwin. Bound in crimson leather decorated with gold moleiro.com/online • moleiro.com Tel. USA +1 305 831 4986 • Tel. UK +44 (0)20 7193 4986 Introduction to the Splendor Solis Splendor Solis, bearing in mind that most about the conditions surrounding the pro- contemporary readers would have consid- duction of the illuminated manuscript: we commentary volume erable diffi culty understanding much of know of numerous sources that were drawn Jörg Völlnagel the content: upon by both the text and the illustrations, which were to have a lasting effect on the Art historian, research associate at the The Alchemy Splendor Solis. -

Dance, Music, Art, and Religion Edited by Tore Ahlback SCRIPTA INSTITUTI DONNERIANI ABOENSIS

Dance, Music, Art, and Religion Edited by Tore Ahlback SCRIPTA INSTITUTI DONNERIANI ABOENSIS XVI DANCE, MUSIC, ART, AND RELIGION Based on Papers Read at the Symposium on Dance, Music, and Art in Religions Held at Åbo, Finland, on the 16th-18th of August 1994 Edited by Tore Ahlbäck, Distributed by ALMQUIST & WIKSELL INTERNATIONAL STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN Dance, Music, Art, and Religion Dance, Music, Art, and Religion Based on Papers Read at the Symposium on Dance, Music, and Art in Religions Held at Åbo, Finland, on the 16th-18th August 1994 Edited by Tore Ahlbäck Published by The Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History Åbo Finland Distributed by Almqvist & Wiksell International Stockholm, Sweden ISSN 0582-3226 ISBN 951-650-834-0 Printed in Finland by Åbo Akademi University Printing Press Turku 1996 Contents Editorial Note 7 DESMOND AYIM-ABOAGYE Art, Music and Religious Experience in Libation Pouring of Akan Religion 9 UMAR HABILA DADEM DANFULANI Rituals as Dance and Dance as Rituals. The Drama of Kok Nji and Other Festivals in the Religious Experience of the Ngas, Mupun and Mwaghavul in Nigeria 27 VALERIE DEMARINIS With Dance and Drum. A Psychocultural Investigation of the Ritual Meaning-Making System of an Afro-Brazilian, Macumba Community in Salvador, Brazil 59 MONICA ENGELHART The Dancing Picture — The Ritual Dance of Native Australians 75 RAGNHILD BJERRE FINNESTAD Images as Messengers of Coptic Identity. An Example from Con- temporary Egypt 91 MARIANNE GÖRMAN The Necklace as a Divine Symbol and as a Sign of Dignity -

Introduction: the Nation and the Spectral Wandering Jew

Notes Introduction: The Nation and the Spectral Wandering Jew 1. According to legend, Christ was driven from Ahasuerus's doorstep where he stopped to rest. In response to the jew's action of striking him while shouting, 'Walk faster!', Christ replied, 'I go, but you will walk until I come again!' (Anderson, Legend: 11). By way of this curse, Christ figuratively transferred his burdensome cross to the jew. 2. As Hyam Maccoby explains, 'One of the strongest beliefs of medieval Christians was that the Second Coming of Christ could not take place until the Jews were con verted to Christianity. (Marvell's "till the conversion of the jews" means simply "till the millennium".) The Jews, therefore, had to be preserved; otherwise the Second Coming could not take place' (239). According to Michael Ragussis, British conversionist societies justified their activities by claiming to 'aid in this divine plan, and with a kind of reverse logic their establishment was viewed as a sign of the proximity of the Second Coming' (Figures: 5). 3. Roger of Wendover's Flores historiarwn and Matthew Paris's Chrmzica majora from . the early thirteenth century provide all of the details of the legend, but the transgressor in their versions is Pilate's doorkeeper, a Roman named Cartaphilus, and not a Jew (Anderson, Legend 16-21). \Vhile in certain Italian versions of this tale the accursed wanderer is a Jew (19), he is not described as Jewish in the British legend until the early seventeenth century. The conjunction between the entry of this legend and Jews into England is in keeping with N.J. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Newton's Dark Secrets

Original broadcast: November 15, 2005 BEFORE WATCHING Newton’s Dark Secrets 1 Ask students what they know about Sir Isaac Newton. List student answers on the board. Where and when did he live? What did he do? PROGRAM CONTENTS What is he most known for? NOVA presents the life and science of 2 Organize students into three Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), one of groups. As they watch, have each the greatest scientists who ever lived. group take notes on one of the following topics: Newton’s key scientific and mathematical discov- The program: eries, his religious journey, and his • chronicles Newton’s upbringing in the early part of the work in alchemy. Scientific Revolution. • recounts Newton’s attendance at Trinity College at Cambridge University in England, where he studied the latest scientific ideas, AFTER WATCHING and his return to his hometown of Woolsthorpe four years later when the plague struck Cambridge. 1 Have students who took notes on • reviews the advances Newton made in gravity, calculus, and the the same topic meet and present their notes. Ask the following composition of light while he was at Woolsthorpe. questions as different teams • relates Newton’s return to Cambridge, where he was appointed the share their notes: What were some Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a chair currently held by physicist of Newton’s mathematical and Stephen Hawking. scientific contributions? Which are • reports how Newton solved the problem of chromatic aberration in important in the world today? What role did religion play in his life? refracting telescopes by designing and building a reflecting telescope Why was he interested in alchemy? based on mirrors rather than lenses. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored

ALCHEMY REDISCOVERED AND RESTORED BY ARCHIBALD COCKREN WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXTRACTION OF THE SEED OF METALS AND THE PREPARATION OF THE MEDICINAL ELIXIR ACCORDING TO THE PRACTICE OF THE HERMETIC ART AND OF THE ALKAHEST OF THE PHILOSOPHER TO MRS. MEYER SASSOON PHILADELPHIA, DAVID MCKAY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1941 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren. This web edition created and published by Global Grey 2013. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS FOREWORD PART I. HISTORICAL CHAPTER I. BEGINNINGS OF ALCHEMY CHAPTER II. EARLY EUROPEAN ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER III. THE STORY OF NICHOLAS FLAMEL CHAPTER IV. BASIL VALENTINE CHAPTER V. PARACELSUS CHAPTER VI. ALCHEMY IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES CHAPTER VII. ENGLISH ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER VIII. THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN PART II. THEORETICAL CHAPTER I. THE SEED OF METALS CHAPTER II. THE SPIRIT OF MERCURY CHAPTER III. THE QUINTESSENCE (I) THE QUINTESSENCE. (II) CHAPTER IV. THE QUINTESSENCE IN DAILY LIFE PART III CHAPTER I. THE MEDICINE FROM METALS CHAPTER II. PRACTICAL CONCLUSION 'AUREUS,' OR THE GOLDEN TRACTATE SECTION I SECTION II SECTION III SECTION IV SECTION V SECTION VI SECTION VII THE BOOK OF THE REVELATION OF HERMES 1 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS said to be found in the Valley of Ebron, after the Flood. 1. I speak not fiction, but what is certain and most true. 2. What is below is like that which is above, and what is above is like that which is below for performing the miracle of one thing. -

The Sun Invincible Timothy J

The Sun Invincible Timothy J. O’Neill, FRC In this article, Timothy J. O’Neill, a member of the Rosicrucian Order, AMORC’s International Research Council, explores the esoteric meaning of the Sun in Alchemy and the Mystery Religions. he shaman, alchemist, and to be seen as the localization of the great blacksmith all share one surprising universal driving force of evolution and Tand outstanding characteristic: they life itself. are all masters of fire. And each of these fire As one of the great philosophical masters is expert in the art of transformation. and mystical traditions, alchemy can be From the awakening of human simply defined as the art of accelerating awareness, it was clear that fire and heat nature’s slow and gradual work of universal contain the mystery of change, death, and perfection as exemplified in the process of rebirth. That which is burned is often the biological evolution. In our context, it is grounds for new life, as anyone who has the solar fire of evolution which speeds watched the process of plant re-growth alchemy’s refined work of perfection. following a forest fire will understand. It As the alchemists quickly learned, was also apparent to earliest people that though, the unbridled heart of the solar the greatest source of fire—that embodied force burns too quickly and intensely in the Sun—was the origin or basis of all by itself. That is why, in the practice of life and being. The warmth of the flesh, alchemy, the Sun is rarely found apart from the heat of the internal organs, the passion, its natural companion, the moon, which excitement, and enthusiasm for life, all this is characterized by its moist, cooling, was likened to the gentle warmth of the vaporous currents. -

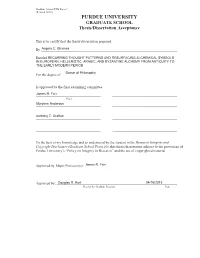

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013).