Middle Byzantine Pottery in Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illumination Underfoot the Design Origins of Mamluk Carpets by Peter Samsel

Illumination Underfoot The Design Origins of Mamluk Carpets by Peter Samsel Sophia: The Journal of Traditional Studies 10:2 (2004), pp.135-61. Mamluk carpets, woven in Cairo during the period of Mamluk rule, are widely considered to be the most exquisitely beautiful carpets ever created; they are also perhaps the most enigmatic and mysterious. Characterized by an intricate play of geometrical forms, woven from a limited but shimmering palette of colors, they are utterly unique in design and near perfect in execution.1 The question of the origin of their design and occasion of their manufacture has been a source of considerable, if inconclusive, speculation among carpet scholars;2 in what follows, we explore the outstanding issues surrounding these carpets, as well as possible sources of inspiration for their design aesthetic. Character and Materials The lustrous wool used in Mamluk carpets is of remarkably high quality, and is distinct from that of other known Egyptian textiles, whether earlier Coptic textiles or garments woven of wool from the Fayyum.3 The manner in which the wool is spun, however – “S” spun, rather than “Z” spun – is unique to Egypt and certain parts of North Africa.4,5 The carpets are knotted using the asymmetrical Persian knot, rather than the symmetrical Turkish knot or the Spanish single warp knot.6,7,8 The technical consistency and quality of weaving is exceptionally high, more so perhaps than any carpet group prior to mechanized carpet production. In particular, the knot counts in the warp and weft directions maintain a 1:1 proportion with a high degree of regularity, enabling the formation of polygonal shapes that are the most characteristic basis of Mamluk carpet design.9 The red dye used in Mamluk carpets is also unusual: lac, an insect dye most likely imported from India, is employed, rather than the madder dye used in most other carpet groups.10,11 Despite the high degree of technical sophistication, most Mamluks are woven from just three colors: crimson, medium blue and emerald green. -

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter Suzanne C. Walsh A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art History. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Jaroslav Folda Dr. Eduardo Douglas Dr. Dorothy Verkerk Abstract Suzanne C. Walsh: The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter (Under the direction of Dr. Jaroslav Folda) The Saint Louis Psalter (Bibliothèque National MS Lat. 10525) is an unusual and intriguing manuscript. Created between 1250 and 1270, it is a prayer book designed for the private devotions of King Louis IX of France and features 78 illustrations of Old Testament scenes set in an ornate architectural setting. Surrounding these elements is a heavy, multicolored border that uses a repeating pattern of a leaf encircled by vines, called a rinceau. When compared to the complete corpus of mid-13th century art, the Saint Louis Psalter's rinceau design has its origin outside the manuscript tradition, from architectural decoration and metalwork and not other manuscripts. This research aims to enhance our understanding of Gothic art and the interrelationship between various media of art and the creation of the complete artistic experience in the High Gothic period. ii For my parents. iii Table of Contents List of Illustrations....................................................................................................v Chapter I. Introduction.................................................................................................1 -

The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field

CHAPTER 11 The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field We touched on the grottesche as a mode of aggregating decorative fragments into structures which could display the artist’s mastery of design and imagi- native invention.1 The grottesche show the far-reaching transformation which had occurred in the conception and handling of ornament, with the exaltation of antiquity and the growth of ideas of artistic style, fed by a confluence of rhe- torical and Aristotelian thought.2 They exhibit a decorative style which spreads through painted façades, church and palace decoration, frames, furnishings, intermediary spaces and areas of ‘licence’ such as gardens.3 Such proliferation shows the flexibility of candelabra, peopled acanthus or arabesque ornament, which can be readily adapted to various shapes and registers; the grottesche also illustrate the kind of ornament which flourished under printing. With their lack of narrative, end or occasion, they can be used throughout a context, and so achieve a unifying decorative mode. In this ease of application lies a reason for their prolific success as the characteristic form of Renaissance ornament, and their centrality to later historicist readings of ornament as period style. This appears in their success in Neo-Renaissance style and nineteenth century 1 The extant drawings of antique ornament by Giuliano da Sangallo, Amico Aspertini, Jacopo Ripanda, Bambaia and the artists of the Codex Escurialensis are contemporary with—or reflect—the exploration of the Domus Aurea. On the influence of the Domus Aurea in the formation of the grottesche, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, Leiden: Brill, 1969); idem, “Ghirlandaio et l’antique”, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 39 (1962), 419– 55; idem, Le Logge di Raffaello: Maestro e bottega di fronte all’antica (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1977, 2nd ed. -

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington Principal Investigators: Jennifer B. Leynes Kelly E. Wiles Prepared by: RGA, Inc. 259 Prospect Plains Road, Building D Cranbury, New Jersey 08512 Prepared for: Morris County Department of Planning and Public Works, Division of Planning and Preservation Date: October 15, 2015 BOROUGH OF MADISON MUNICIPAL OVERVIEW: THE BOROUGH OF MADISON “THE ROSE CITY” TOTAL SQUARE MILES: 4.2 POPULATION: 15,845 (2010 CENSUS) TOTAL SURVEYED HISTORIC RESOURCES: 136 SITES LOST SINCE 19861: 21 • 83 Pomeroy Road: demolished between 2002-2007 • 2 Garfield Avenue: demolished between 1987-1991 • Garfield Avenue: demolished c. 1987 • Madison Golf Club Clubhouse: demolished 2007 • George Wilder House: demolished 2001 • Barlow House: demolished between 1987-1991 • Bottle Hill Tavern: demolished 1991 • 13 Cross Street: demolished between 1987-1991 • 198 Kings Road: demolished between 1987-1991 • 92 Greenwood Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • Wisteria Lodge: demolished 1988 • 196 Greenwood Avenue: demolished between 2002-2007 • 194 Rosedale Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • C.A. Bruen House: demolished between 2002-2006 • 85 Green Avenue: demolished 2015 • 21, 23, 25 and 63 Ridgedale Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape/Bottle Hill Historic District: demolished c. 2013 • 21 and 23 Cook Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape: demolished between 1995-2002 RESOURCES DOCUMENTED BY HABS/HAER/HALS: • Bottle Hill Tavern (117 Main -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

Lot Description LOW Estimate HIGH Estimate 2000 German Rococo Style Silvered Wall Mirror, of Oval Form with a Wide Repoussé F

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate German Rococo style silvered wall mirror, of oval form with a wide repoussé frame having 2000 'C' scroll cartouches, with floral accents and putti, 27"h x 20.5"w $ 300 - 500 Polychrome Murano style art glass vase, of tear drop form with a stick neck, bulbous body, and resting on a circular foot, executed in cobalt, red, orange, white, and yellow 2001 wtih pulled lines on the neck and large mille fleur designs on the body, the whole cased in clear glass, 16"h x 6.75"w $ 200 - 400 Bird's nest bubble bowl by Cristy Aloysi and Scott Graham, executed in aubergine glass 2002 with slate blue veining, of circular form, blown with a double wall and resting on a circular foot, signed Aloysi & Graham, 6"h x 12"dia $ 300 - 500 Monumental Murano centerpiece vase by Seguso Viro, executed in gold flecked clear 2003 glass, having an inverted bell form with a flared rim and twisting ribbed body, resting on a ribbed knop rising on a circular foot, signed Seguso Viro, 20"h x 11"w $ 600 - 900 2004 No Lot (lot of 2) Art glass group, consisting of a low bowl, having an orange rim surmounting the 2005 blue to green swirl decorated body 3"h x 11"w, together with a French art glass bowl, having a pulled design, 2.5"h x 6"w $ 300 - 500 Archimede Seguso (Italian, 1909-1999) art glass sculpture, depicting the head of a lady, 2006 gazing at a stylized geometric arch in blue, and rising on an oval glass base, edition 7 of 7, signed and numbered to underside, 7"h x 19"w $ 1,500 - 2,500 Rene Lalique "Tortues" amber glass vase, introduced 1926, having a globular form with a 2007 flared mouth, the surface covered with tortoises, underside with molded "R. -

The Grotesque in El Greco

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME © Författare: Lena Beckman Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Höstterminen 2019 Handledare: Johan Eriksson ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala Universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Lena Beckman Titel och Undertitel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Engelsk titel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Handledare Johan Eriksson Ventileringstermin: Hösttermin (år) Vårtermin (år) Sommartermin (år) 2019 2019 Content: This study attempts to investigate the grotesque in four paintings of the artist Domenikos Theotokopoulos or El Greco as he is most commonly called. The concept of the grotesque originated from the finding of Domus Aurea in the 1480s. These grottoes had once been part of Nero’s palace, and the images and paintings that were found on its walls were to result in a break with the formal and naturalistic ideals of the Quattrocento and the mid-renaissance. By the end of the Cinquecento, artists were working in the mannerist style that had developed from these new ideas of innovativeness, where excess and artificiality were praised, and artists like El Greco worked from the standpoint of creating art that were more perfect than perfect. The grotesque became an end to reach this goal. While Mannerism is a style, the grotesque is rather an effect of the ‘fantastic’.By searching for common denominators from earlier and contemporary studies of the grotesque, and by investigating the grotesque origin and its development through history, I have summarized the grotesque concept into three categories: between form, beyond language and beside the sublime. -

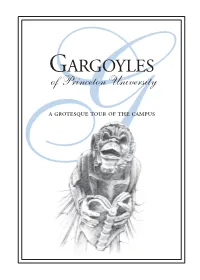

Gargoyles of Princeton University Ga Grotesque Tour of the Campus

GARGOYLES of Princeton University Ga grotesque tour of the campus 1 2 Here we were taught by men and Gothic towers democracy and faith and righteousness and love of unseen things that do not die. H. E. Mierow ’14 or centuries scholars have asked why gargoyles inhabit their most solemn churches and institutions. Fantastic explanations have come downF from the Middle Ages. Some art historians believe that gargoyles were meant to depict evil spirits over which the Christian church had triumphed. One theory suggests that these devils were frozen in stone as they fled the church. Supposedly, Christ set these spirits to work as useful examples to men instead of sending them straight to damnation. Others say they kept evil spirits away. Psychologists suggest that gargoyles represent the fears and superstitions of medieval men. As life became more secure, the gargoyles became more comical and whimsical. This little book introduces you to some men, women, and beasts you may have passed a hundred times on the campus but never noticed. It invites you to visit some old favorites. A pair of binoculars will bring you face-to-face with second- and third- story personalities. Why does Princeton have gargoyles and grotesques? Here is one excuse: … If the most fanciful and wildest sculptures were placed on the Gothic cathedrals, should they be out of place on the walls of a secular educational establishment? (“Princeton’s Gargoyles,” New York Sun, May 13, 1927) Note: Taking some technical license, the creatures and carvings described in this publication are referred to as “gargoyles” and “grotesques.” Typically, gargoyles are defined as such only when they also serve to convey water away from a building. -

Graded-In Textiles

Graded-In Textiles For a list of each of our partner commpany’s patterns with Boss • Indicate GRADED-IN TEXTILE on your order and Boss Design Design Grades visit www.bossdesign.com. To order memo will order the fabric and produce the specified furniture. samples visit the websites or call the numbers listed below. • Boss Design reserves the right to adjust grades to accommodate price changes received from our suppliers. • Refer to our website www.bossdesign.com for complete pattern memo samples: www.arc-com.com or 800-223-5466 lists with corresponding Boss Design grades. Fabrics priced above our grade levels and those with exceptionally large repeats are indicated with “CALL”. Please contact Customer Service for pricing. • Orders are subject to availability of the fabric from the supplier . • Furniture specified using multi-fabric applications or contrasting welts be up charged. memo samples: www.architex-ljh.com or 800-621-0827 may • Textiles offered in the Graded-in Textiles program are non- standard materials and are considered Customer’s Own Materials (COM). Because COMs are selected by and used at the request of a user, they are not warranted. It is the responsibility of the purchaser to determine the suitability of a fabric for its end use. memos: www.paulbraytondesigns.com or 800-882-4720 • In the absence of specific application instructions, Boss Design will apply the fabric as it is sampled by the source and as it is displayed on their website. memo samples: www.camirafabrics.com or 616 288 0655 • MEMO SAMPLES MUST BE ORDERED DIRECTLY FROM THE FABRIC SUPPLIER. -

Corinth, 1987: South of Temple E and East of the Theater

CORINTH, 1987: SOUTH OF TEMPLE E AND EAST OF THE THEATER (PLATES 33-44) ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens were conductedin 1987 at Ancient Corinth south of Temple E and east of the Theater (Fig. 1). In both areas work was a continuationof the activitiesof 1986.1 AREA OF THE DECUMANUS SOUTH OF TEMPLE E ROMAN LEVELS (Fig. 1; Pls. 33-37:a) The area that now lies excavated south of Temple E is, at a maximum, 25 m. north-south by 13.25 m. east-west. The earliest architecturalfeature exposed in this set of trenches is a paved east-west road, identified in the 1986 excavation report as the Roman decumanus south of Temple E (P1. 33). This year more of that street has been uncovered, with a length of 13.25 m. of paving now cleared, along with a sidewalk on either side. The street is badly damaged in two areas, the result of Late Roman activity conducted in I The Greek Government,especially the Greek ArchaeologicalService, has again in 1987 made it possible for the American School to continue its work at Corinth. Without the cooperationof I. Tzedakis, the Director of the Greek ArchaeologicalService, Mrs. P. Pachyianni, Ephor of Antiquities of the Argolid and Corinthia, and Mrs. Z. Aslamantzidou, epimeletria for the Corinthia, the 1987 season would have been impossible. Thanks are also due to the Director of the American School of Classical Studies, ProfessorS. G. Miller. The field staff of the regular excavationseason includedMisses A. A. Ajootian,G. L. Hoffman, and J. -

Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets Carol Bier, the Textile Museum

Graduate Theological Union From the SelectedWorks of Carol Bier February, 1996 Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets Carol Bier, The Textile Museum Available at: https://works.bepress.com/carol_bier/49/ 1 IU1 THE TEXTILE MUSEUM Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets CAROL BIER Curator, Eastern Hemisphere Collections The Textile Museum Studio photography by Franko Khoury MAJOR RUG-PRODUCING REGIONS OF THE WORLD Rugs from these regions share stylistic and technical features that enable us to identify major regional groupings as shown. Major Regional Groupings BSpanish (l5th century) ..Egypto-Syrian (l5th century) ItttmTurkish _Indian Persian Central Asian :mumm Chinese ~Caucasian 22 Major rug-producing regions of the world. Map drawn by Ed Zielinski ORIENTAL CARPETS reached a peak in production language, one simply weaves a carpet. in the late nineteenth century, when a boom in market Wool i.s the material of choice for carpets woven demand in Europe and America encouraged increased among pastoral peoples. Deriving from the fleece of a *24 production in Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus.* Areas sheep, it is a readily available and renewable resource. east of the Mediterranean Sea at that time were Besides fleece, sheep are raised and tended in order to referred to as. the Orient (in contrast to the Occident, produce dairy products, meat, lard and hide. The body which referred to Europe). To study the origins of these hair of the sheep yields the fleece. I t is clipped annually carpets and their ancestral heritage is to embark on a or semi-annually; the wool is prepared in several steps journey to Central Asia and the Middle East, to regions that include washing, grading, carding, spinning and of low rainfall and many sheep, to inhospitable lands dyeing. -

View Fast Facts

FAST FACTS Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe “Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe.” Gale, 2019, www.gale.com. Writings by Edgar Allan Poe • Tamerlane and Other Poems (poetry) 1827 • Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (poetry) 1829 • Poems (poetry) 1831 • The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, North America: Comprising the Details of a Mutiny, Famine, and Shipwreck, During a Voyage to the South Seas; Resulting in Various Extraordinary Adventures and Discoveries in the Eighty-fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude (novel) 1838 • Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (short stories) 1840 • The Raven, and Other Poems (poetry) 1845 • Tales by Edgar A. Poe (short stories) 1845 • Eureka: A Prose Poem (poetry) 1848 • The Literati: Some Honest Opinions about Authorial Merits and Demerits, with Occasional Words of Personality (criticism) 1850 Major Themes The most prominent features of Edgar Allan Poe's poetry are a pervasive tone of melancholy, a longing for lost love and beauty, and a preoccupation with death, particularly the deaths of beautiful women. Most of Poe's works, both poetry and prose, feature a first-person narrator, often ascribed by critics as Poe himself. Numerous scholars, both contemporary and modern, have suggested that the experiences of Poe's life provide the basis for much of his poetry, particularly the early death of his mother, a trauma that was repeated in the later deaths of two mother- surrogates to whom the poet was devoted. Poe's status as an outsider and an outcast--he was orphaned at an early age; taken in but never adopted by the Allans; raised as a gentleman but penniless after his estrangement from his foster father; removed from the university and expelled from West Point--is believed to account for the extreme loneliness, even despair, that runs through most of his poetry.