Giuseppe Verdi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blandade Insatser I Tidig Verdi

Blandade insatser i tidig Verdi Giuseppe Verdi: I due Foscari Solister: Vladimir Stoyanov, Stefan Pop, Maria Katzarava, Giacomo Prestia, m.fl. Filharmonica Arturo Toscanini & Coro del Teatro Regio di Parma Dirigent: Paolo Arrivabeni Dynamic CDS7865 [2 CD] Giuseppe Verdi: Attila Solister: Ildebrando d’Arcangelo, Liudmyla Monastyrska, Stefano La Colla, George Petean, m.fl. Münchner Rundfunkorchester & Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks Dirigent: Ivan Repusic BR Klassik 900330 [2 CD] Efter att ha förlorat sin fru, sina två barn och fått uppleva ett praktfiasko i sin andra opera Un giorno di regno, gjorde Verdi en rejäl comeback med Nabucco 1842 som blev storsuccé. Därefter komponerade han hela 13 operor under de s.k. “Anni di galera”* (1843-50), som för Verdi innebar ett oupphörligt, intensivt arbete, där han tidvis till och med jobbade på flera verk samtidigt. Bland dessa verk har egentligen baraMacbeth varit given i standardrepertoaren, vilken de flesta av hans operor efter 1851 (från Rigoletto) tillhör. På 1970-talet fick operorna från “Anni di galera” en renässans på skivbolaget Philips (numera Decca), mycket tack vare den trogne Verdispecialisten Lamberto Gardelli. När det gäller operorna I due Foscari och Attila så har Gardellis upptagningar varit referensinspelningar för många; den förstnämnda nästan helt utan konkurrens och den andra har endastMutis inspelning på EMI/Warner kunnat mäta sig med om man enbart räknar med kommersiella inspelningar. I maj släpptes en inspelning av vardera operan, på skivmärkena Dynamic respektive BR Klassik. Dynamic har producerat en rad Verdi-inspelningar, där några ha varit acceptabla utan att på något sätt vara i närheten av dem från den gamla goda tiden. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 118, 1998-1999

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 1 I O Z AWA ' T W E N T Y- F I F 1 H ANNIVERSARY SEASO N 1 1 8th Season • 1 998-99 Bring your Steinway: < With floor plans from acre gated community atop 2,100 to 5,000 square feet, prestigious Fisher Hill you can bring your Concert Jointly marketed by Sotheby's Grand to Longyear. International Realty and You'll be enjoying full-service, Hammond Residential Real Estate. single-floor condominium living at Priced from $1,100,000. its absolutefinest, all harmoniously Call Hammond Real Estate at located on an extraordinary eight- (617) 731-4644, ext. 410. LONGYEAR at Jisner Jiill BROOKLINE Seiji Ozawa, Music Director 25TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Eighteenth Season, 1998-99 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R. Willis Leith, Jr., Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Deborah B. Davis Edna S. Kalman Vincent M. O'Reilly Gabriella Beranek Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read James E Cleary Nancy J. Fitzpatrick Mrs. August R. Meyer Hannah H. Schneider John F. Cogan, Jr. Charles K. Gifford, Richard P. Morse Thomas G. Sternberg Julian Cohen ex-ojficio Mrs. Robert B. Stephen R. Weiner William F. Connell Avram J. Goldberg Newman Margaret Williams- William M. Crozier, Jr. Thelma E. Goldberg Robert P. O'Block, DeCelles, ex-qfficio Nader F Darehshori Julian T. Houston ex-ojficio Life Trustees Vernon R. -

Ildar Abdrazakov Las Versiones Del Demonio

ENTREVISTA Ildar Abdrazakov Las versiones del demonio por Ingrid Haas ldar Abdrazakov es uno de los grandes bajos en la actualidad. A sus 39 años, goza ya de una carrera sólida y llena de éxitos en teatros tan importantes como la Scala de Milán, Iel Metropolitan Opera House de Nueva York, Washington Opera, Los Ángeles Ópera, Royal Opera House de Londres, Opéra Bastille de París, el Teatro Mariinsky, el Liceu de Barcelona, el Real de Madrid, la Ópera de Montecarlo, la Ópera de San Francisco, la Ópera Estatal de Viena y la Ópera Estatal de Baviera, entre otras. La voz de Abdrazakov ha conquistado a los públicos más exigentes y a directores de orquesta de la talla de Riccardo Muti, James Levine, Valery Gergiev, Gianandrea Noseda, Anthony Pappano, Riccardo Chailly y Bertrand de Billy, sólo por nombrar a algunos. “En las tres Con su cavernoso timbre, innegable musicalidad y gallarda versiones de presencia escénica, Abdrazakov ha cantado una amplia gama de Mefistófeles que he roles que van desde Fígaro en Le nozze di Figaro de Mozart, el rol cantado, mi Fausto titular y Leporello en Don Giovanni, Moïse en Moïse et Pharaon, ha sido siempre Assur en Semiramide, Don Basilio en Il Barbiere di Siviglia, las Ramón Vargas” tres de Rossini, Oroveso en Norma de Bellini, Méphistophélès Foto: Sergei Misenko en las versiones de Faust de Gounod y La damnation de Faust de Berlioz, el rol principal de Mefistofelede Boito, los Cuatro Sí, en efecto. Vine a cantar hace unos años a la Ciudad de México: Villanos de Les contes d’Hoffmann, Walter en Luisa Miller así un recital en la Sala Nezahualcóyotl y el Requiem de Verdi en como Oberto y Attila en las óperas homónimas de Verdi, Dosifei en Bellas Artes. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

1 CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se Incluye Un Listado Con Las

CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se incluye un listado con las representaciones de Aida, de Giuseppe Verdi, en la historia del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estreno absoluto: Ópera del Cairo, 24 de diciembre de 1871. Estreno en Barcelona: Teatro Principal, 16 abril 1876. Estreno en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 25 febrero 1877 Última representación en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 30 julio 2012 Número total de representaciones: 454 TEMPORADA 1876-1877 Número de representaciones: 21 Número histórico: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Fechas: 25 febrero / 3, 4, 7, 10, 15, 18, 19, 22, 25 marzo / 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 18, 22, 27 abril / 2, 10, 15 mayo 1877. Il re: Pietro Milesi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Carolina de Cepeda (febrero, marzo) Teresina Singer (abril, mayo) Radamès: Francesco Tamagno Ramfis: Francesc Uetam (febrero y 3, 4, 7, 10, 15 marzo) Agustí Rodas (a partir del 18 de marzo) Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Argimiro Bertocchi Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1877-1878 Número de representaciones: 15 Número histórico: 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Fechas: 29 diciembre 1877 / 1, 3, 6, 10, 13, 23, 25, 27, 31 enero / 2, 20, 24 febrero / 6, 25 marzo 1878. Il re: Raffaele D’Ottavi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Adele Bianchi-Montaldo Radamès: Carlo Bulterini Ramfis: Antoine Vidal Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Antoni Majjà Director: Eusebi Dalmau 1 7-IV-1878 Cancelación de ”Aida” por indisposición de Carlo Bulterini. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

The Royal Opera Celebrates 25 Years of Richard Eyre's Iconic Production

02/10/2019 The Royal Opera celebrates 25 years of Richard Eyre’s iconic production of La traviata La traviata, Act I, The Royal Opera © 2019 ROH. Photographed by Tristram Kenton. Verdi’s eternally popular La traviata returns to the Royal Opera House in December 2019. This Season we celebrate the 25th anniversary of the premiere of Richard Eyre’s magnificent production, which perfectly encapsulates the colour, glamour and splendour of 19th-century Paris against which the heroine’s tragedy unfolds. For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media From lyrical arias to vibrant choruses, La traviata contains some of Verdi’s finest and best-known music. Based on Alexandre Dumas fils’s novel and play La Dame aux camélias, itself based on the life of Dumas’ own lover Marie Duplessis, La traviata tells the story of the courtesan Violetta and the passionate love she feels for Alfredo Germont – a love that leads her to make the ultimate sacrifice. Verdi’s most romantic opera has delighted audiences around the world for more than 150 years and Richard Eyre’s wonderful production has been a staple of The Royal Opera’s repertory since 1994. It is revived nearly every Season and is an unmissable experience for opera fans and newcomers alike. For this long-running revival, five internationally-acclaimed singers perform the role of Violetta: the Armenian soprano Hrachuhi Bassenz, the Azerbaijani soprano Dinara Alieva, the Russian sopranos Kristina Mkhitaryan and Vlada Borovko (the latter a former Royal Opera Jette Parker Young Artist) and the Polish soprano Aleksandra Kurzak. -

Biography: Fabio Armiliato

Biography: Fabio Armiliato Internationally renewed tenor Fabio Armiliato is acclaimed by the public thanks to his unique vocal style, his impressive upper register and his dramatic abilities and charisma that infuses in his characters. He made his opera debut as Gabriele Adorno in Simon Boccanegra in his hometown Genoa, where he graduated at the Conservatory Niccolo Paganini, after which his career set off leading him to address many important roles for his register in the most prestigious theatres in the world. In 1993 debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York with Il Trovatore, followed by Aida, Cavalleria Rusticana, Don Carlo, Simon Boccanegra, Tosca, Fedora, Madama Butterfly. Especially his performance of Andrea Chènier at the Met is considered one of his most iconic roles, receiving the proclamation from the critics of “best Chénier of our times”. Equally importance Fabio Armiliato gave to the role of Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, sung amongst others at La Scala in Milan, at the Gran Teatre del Liceu and the New National Theatre in Tokyo. During the period from 1990 to 1996, he performed in the Opera of Antwerp on a cycle dedicated to Giacomo Puccini, in production directed by Robert Carsen interpreting Tosca, Don Carlo and Manon Lescaut. Armiliato is a refined interpreter of Mario Cavaradossi in Tosca with more than 150 performances of the title, he has been acclaimed in this role in the most prestigious Opera Houses including La Scala in Milan, conducted by Lorin Maazel, and the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden in London under the baton of Antonio Pappano in 2006. -

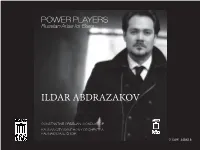

Ildar Abdrazakov

POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR KAUNAS CITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KAUNAS STATE CHOIR 1 0 13491 34562 8 ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL iconic characters The dynamics of power in Russian opera and its most DE 3456 (707) 996-3844 • © 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., © 2013 Delos Productions, 95476-9998 CA Sonoma, 343, Box P.O. (800) 364-0645 [email protected] www.delosmusic.com CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR ORBELIAN, CONSTANTINE ORCHESTRA CITY SYMPHONY KAUNAS CHOIR STATE KAUNAS Arias from: Arias Rachmaninov: Aleko the Tsar & Ludmila,Glinka: A Life for Ruslan Igor Borodin: Prince Boris GodunovMussorgsky: The Demon Rubinstein: Onegin, Iolanthe Eugene Tchaikovsky: Peace and War Prokofiev: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sadko 66:49 Time: Total Russian Arias for Bass ABDRAZAKOV ILDAR POWER PLAYERS ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV 1. Sergei Rachmaninov: Aleko – “Ves tabor spit” (All the camp is asleep) (6:19) 2. Mikhail Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “Farlaf’s Rondo” (3:34) 3. Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “O pole, pole” (Oh, field, field) (11:47) 4. Alexander Borodin: Prince Igor – “Ne sna ne otdykha” (There’s no sleep, no repose) (7:38) 5. Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov – “Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani” (At Kazan, where long ago I fought) (2:11) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon – “Na Vozdushnom Okeane” (In the ocean of the sky) (5:05) 7. Piotr Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Liubvi vsem vozrasty pokorny” (Love has nothing to do with age) (5:37) 8. Tchaikovsky: Iolanthe – “Gospod moi, yesli greshin ya” (Oh Lord, have pity on me!) (4:31) 9. -

25Th Anniversary

25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture 25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award Arts Patronage Montblanc de la Culture 25th Anniversary Arts Patronage Award 1992 25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award 2016 Anniversary 2016 CONTENT MONTBLANC DE LA CULTURE ARTS PATRONAGE AWARD 25th Anniversary — Preface 04 / 05 The Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award 06 / 09 Red Carpet Moments 10 / 11 25 YEARS OF PATRONAGE Patron of Arts — 2016 Peggy Guggenheim 12 / 23 2015 Luciano Pavarotti 24 / 33 2014 Henry E. Steinway 34 / 43 2013 Ludovico Sforza – Duke of Milan 44 / 53 2012 Joseph II 54 / 63 2011 Gaius Maecenas 64 / 73 2010 Elizabeth I 74 / 83 2009 Max von Oppenheim 84 / 93 2 2008 François I 94 / 103 3 2007 Alexander von Humboldt 104 / 113 2006 Sir Henry Tate 114 / 123 2005 Pope Julius II 124 / 133 2004 J. Pierpont Morgan 134 / 143 2003 Nicolaus Copernicus 144 / 153 2002 Andrew Carnegie 154 / 163 2001 Marquise de Pompadour 164 / 173 2000 Karl der Grosse, Hommage à Charlemagne 174 / 183 1999 Friedrich II the Great 184 / 193 1998 Alexander the Great 194 / 203 1997 Peter I the Great and Catherine II the Great 204 / 217 1996 Semiramis 218 / 227 1995 The Prince Regent 228 / 235 1994 Louis XIV 236 / 243 1993 Octavian 244 / 251 1992 Lorenzo de Medici 252 / 259 IMPRINT — Imprint 260 / 264 Content Anniversary Preface 2016 This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Montblanc Cultural Foundation: an occasion to acknowledge considerable achievements, while recognising the challenges that lie ahead. Since its inception in 1992, through its various yet interrelated programmes, the Foundation continues to appreciate the significant role that art can play in instigating key shifts, and at times, ruptures, in our perception of and engagement with the cultural, social and political conditions of our times. -

00003574.Pdf Pdf.Pdf

1 MARÍA MOLINER FECHAS Y HORARIOS Días 13, 15, 17, 19 y 21 de abril de 2016 20:00 horas (domingo a las 18:00 horas) Funciones de abono: 13, 15, 17, 19 y 21 de abril Duración aproximada: Primer acto: 55 minutos Intervalo 20 minutos Segundo acto: 50 minutos Funciones con audiodescripción: 15 y 17 de abril Función con visita táctil: 17 de abril Para más información, visite la página web: teatrodelazarzuela.mcu.es 2 ÓPERA DOCUMENTAL EN DOS ACTOS Y DIEZ ESCENAS LIBRETO DE LUCÍA VILANOVA MÚSICA DE ANTONI PARERA FONS Unión Musical Ediciones, SL (Madrid 2015) Encargo del Teatro de la Zarzuela Estreno absoluto Nueva producción del Teatro de la Zarzuela 3 MARÍA MOLINER REPARTO MARÍA MOLINER María José Montiel (días 13, 15, 17, 21) Cristina Faus (día 19) FERNANDO RAMÓN Y FERRANDO José Julián Frontal INSPECTORA DEL SEU / CARMEN CONDE Sandra Ferrández GOYANES Sebastià Peris SILLÓN B DE LA RAE Juan Pons EMILIA PARDO BAZÁN Celia Alcedo ISIDRA DE GUZMÁN Y DE LA CERDA María José Suárez GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA Lola Casariego ALMANAQUE Gerardo López, David Oller, Toni Marsol CABALLEROS OSCUROS / Sara Rosique*, Ana María Ramos*, VOCES ACUSADORAS Daniel Huerta*, Mario Villoria* * Miembro del Coro del Teatro de la Zarzuela ACTRICES Carolina Andrés, Lucía Barrado, Eva Boucherite, Aurora Carbonell, Lucía Díaz, Gadea Quintana, Elena Lombao, Rocío Marín, Carmen Soler, Vanesa Vega ACTORES Álex Larumbe, Guillermo Sanjuán Agradecimientos a: Editorial Gredos, Gobierno de Aragón, Real Academia Española Joaquín Dacosta, Leo Castaldi, Paloma Bomé, Inmaculada de -

Marco Boemi Conductor Website

Straussengasse 14 /1 1050 Vienna – Austria Ivan Paley: [email protected] Stefan Astner: [email protected] Marco Boemi Conductor Website: www.viemuc.com Marco Boemi is a conductor and pianist who also graduated law at the Sapienza University of Rome. He performed at the Rome Opera, Teatro alla Scala Milan, The Teatro Regio in Turin, Suntory Hall Tokyo, Bayerische Staatsoper, Wiener Musikverein, Paris Opera Bastille and many other major venues. His extensive symphonic and operatic repertoire includes authors like Verdi, Puccini, Beethoven, Mahler, Wagner, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Rachmaninov, Gershwin and Bernstein. During his, more than 20 years long, career he cooperated with many notable singers, such as Pavarotii, Taddei, Kabaivanska, Netrebko, Obratzova, Gruberova, Borodina, Shicoff, Bruson, Ricciarelli, Burchuladze, Abdrazakov and others and also conducted London Philhamonic Orchestra, all the major Japanese orchestras, World Youth Orchestra, Verdi Orchestra and many others. He gives masterclasses for young pianists, singers and conductors and is considered an expert in Lied music. He has recorded for Decca, TDK, Universal with artist such as Colombara, La Scola, Sabbatini, Armiliato and Dessì. In the year 2013 he conducted Verdi´s “Atilla” for the world opening of the Astana Opera. Later on, a Gala concert with Ildar Abdrazakov at the Royal Opera House Muscat, a Gala concert with Netrebko in Kazan, “La traviata” in Verona, “Il trovatore” in Treviso, “Turandot” in Bogotá, as well as “Don Pasquale” in Helsinki were conducted by Boemi. In April 2016, he has again conducted a Gala concert with © Gianni Netrebko and Eyvazov in Los Angeles. Other highlights of the last seasons include “Aida” in Livorno, Pisa and Rovigo, “Il tabarro / I Pagliacci” in Helsinki, “Nabucco” in Lima and “Porgy and Bess” at the Tatar State Opera in Kazan.