Layla and Majnun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My God's Not Dead, He's Surely Alive He's Living on the Inside Roaring

My God’s not dead, He’s surely ALIVE He’s living on the inside ROARING like a lion 1994 Twenty Years of the House of Prayer 2014 - God’s not Dead Syria Jesus abandoned the changes that have The news this month We have included a taken place in Ireland has been dominated piece from a blog we in recent years and how by the wars in Palestine came across from a our society is becoming and Israel and in Syria monastery in County more Godless than ever and Iraq. We have been Meath. The prior was before. E horrified by images from told of an auction taking Twenty Years Syria of Christians, men, place near the monastery Our theme of twenty women and children, which included some years of the House of D being beheaded and religious artefacts. On Prayer also continues crucified because they going to investigate, he with two articles. One refuse to abandon was horrified to find that reflects on the early days I their faith and convert there was a tabernacle here in the House and to Islam. Harrowing with two Hosts still another talks about the images have been inside! music and how the Music T beamed across the world God’s Not Dead Ministry has evolved of children, beheaded, A couple of articles this over the years in to what maimed and their heads month are on the theme is now SonLight. O put on sticks for all to of ‘God’s Not Dead.’ Ballad of a Viral Video see. This is nothing We recently watched a A servant recounts short of barbaric!! It film of this title here at her thoughts on the R greatly upset me to see the House of Prayer and viral video of Fr. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected]

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Introduction Studying the roots of a particular literary history enables us to better understand the allusions the literature transmits and why we appreciate them. It also allows us to foresee how the literature may progress.1 I will try to keep this attitude in the reader’s mind in offering this brief summary of medieval Persian literature, a formidable task considering the variety and wealth of the texts and documentation on the subject.2 In this study we will pay special attention to the development of the Persian literature over the last millennia, focusing in particular on the initial development and background of various literary genres in Persian. Although the concept of literary genres is rather subjective and unstable,3 reviewing them is nonetheless a useful approach for a synopsis, facilitating greater understanding, deeper argumentation, and further speculation than would a simple listing of dates, titles, and basic biographical facts of the giants of Persian literature. Also key to literary examination is diachronicity, or the outlining of literary development through successive generations and periods. Thriving Persian literature, undoubtedly shaped by historic events, lends itself to this approach: one can observe vast differences between the Persian literature of the tenth century and that of the eleventh or the twelfth, and so on.4 The fourteenth century stands as a bridge between the previous and the later periods, the Mongol and Timurid, followed by the Ṣafavids in Persia and the Mughals in India. Given the importance of local courts and their support of poets and writers, it is quite understandable that literature would be significantly influenced by schools of thought in different provinces of the Persian world.5 In this essay, I use the word literature to refer to the written word adeptly and artistically created. -

From Gastarbeiter to Muslim: Cosmopolitan

FROM GASTARBEITER TO MUSLIM: COSMOPOLITAN LITERARY RESPONSES TO POST-9/11 ISLAMOPHOBIA A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 JOSEPH TWIST SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Contents List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures ........................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Declaration................................................................................................................................ 6 Copyright Statement ................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction: Thinking ‘We’ in Contemporary German Literature Islamophobia and the German Literary Landscape ................................................................... 8 ‘Being-with’: Contemporary Cosmopolitan Theory and the Philosophy of Jean-Luc Nancy. 26 Beyond Monotheism: A Cosmopolitan Understanding of the Divine ..................................... 46 Sufism and Singularity: The Deconstruction of Islam ............................................................ -

Compare and Analyzing Mythical Characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh

WALIA journal 31(S4): 121-125, 2015 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2015 WALIA Compare and analyzing mythical characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh Mohammadtaghi Fazeli 1, Behrooze Varnasery 2, * 1Department of Archaeology, Shushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shushtar, Iran 2Department of Persian literature Shoushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shoushtar Iran Abstract: The content difference in both works are seen in rhetorical Science, the unity of epic tone ,trait, behavior and deeds of heroes and Kings ,patriotism in accordance with moralities and their different infer from epic and mythology . Their similarities can be seen in love for king, obeying king, theology, pray and the heroes vigorous and physical power. Comparing these two works we concluded that epic and mythology is more natural in the Epic of the king than Garshaseb Nameh. The reason that Ferdowsi illustrates epic and mythological characters more natural and tangible is that their history is important for him while Garshaseb Nameh looks on the surface and outer part of epic and mythology. Key words: The epic of the king;.Epic; Mythology; Kings; Heroes 1. Introduction Sassanid king Yazdgerd who died years after Iran was occupied by muslims. It divides these kings into *Ferdowsi has bond thought, wisdom and culture four dynasties Pishdadian, Kayanids, Parthian and of ancient Iranian to the pre-Islam literature. sassanid.The first dynasties especially the first one Garshaseb Nameh has undoubtedly the most shares have root in myth but the last one has its roots in in introducing mythical and epic characters. This history (Ilgadavidshen, 1999) ballad reflexes the ethical and behavioral, trait, for 4) Asadi Tusi: The Persian literature history some of the kings and Garshaseb the hero. -

The Hornet, 1923 - 2006 - Link Page Previous Volume 56, Issue 30 Next Volume 56, Issue 32

New president reveals plans BY GERRI SARABIA "The Sprang Thang was a way of area, "Even if they fix a terrific News Editor getting people to mingle in a meal you can't enjoy it eating in a friendly and casual setting," he dungeon filled with smoke and Johnathan Brostrom is the newly said. "Just bringing students noise." Therefore, he intends on elected Fullerton College Asso- together to eat and listen to music is continuing whatever must be done ciated Student President for fall a big social event here on campus. to improve the situation. semester 1978. For the past year It's a form of communication in the If Brostrom continues to maintain and a half he has served as a sense that everyone is partaking the system, FC students should be senator, and as a pro-tem vice and sharing in a mutually enjoyable looking forward to an organized and president. activity." productive A.S. Student Govern- Brostrom's active interest in Brostrom's list of top priority ment next fall, as in the present school government began after issues for next fall include a administration, led by President attending "Sacramento Seminar," cognitive mapping service and the Howard Perkins. a government research class offered continued improvement and revi- sion of the school cafeteria. Perkins has worked on represen- by FC instructor John Schultz. ting the A.S. Senate to get the six "The cognitive mapping service temporary buildings moved any- "It was a great opportunity for is a process through which students me to gain a whole new perspective where on campus except the Quad will be matched to their teacher's or parking areas, and on the plans on politics," said Brostrom. -

Reading the Story of Majnun Layla Through Qassim Haddad's Poem

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 6, Ver. 8 (June. 2017) PP 57-67 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Reading the Story of Majnun Layla through Qassim Haddad’s Poem Dzia Fauziah, Maman Lesmana Arabic Studies Program, Faculty of Humanities Universitas Indonesia Abstract: Majnun Layla is a popular classic story in the Middle East. It is said that this story inspired Shakespeare to write the story of Romeo and Juliet in Europe. The story spread to several cultures in the world and was rewritten in poetry, romance, drama and film genres. This paper aims to examine the story from the genre of modern poetry written by Qassim Haddad, a Bahrain poet. This research uses library data, both print and electronic, as research corpus and reference. The method used in this paper is the qualitative method, which prioritises words rather than numbers and emphasises quality over quantity. The data is presented in the form of analytical descriptive, starting from the description of its structure, until the analysis of its contents. In the analysis, semiotic structuralism is also used, which emphasises the text and its intrinsic elements. From the results of this study, it is found that there are not many images of the MajnunLayla’s love story revealed in the poem because of it is a monologue form and not a narrative, and there are many phrases that are less understandable because the poem is rich in figurative words and unclear connotations. This paper recommends the story to be inspired well, it should be written in the form of a diaphanous and easily digestible poem, rather than prismatic andcomplicated.It is expected to be written in the form of a free and prosaic poem, with simple typography and does not necessarily use too many enjambments. -

Songs by Artist

Karaoke List Songs by Artist Artist Title 10 Cc Donna 10 Cc Dreadlock Holiday 10 Cc Im Mandy Fly Me 10 Cc I'm Not In Love 10 Cc Rubber Bullets 10 Cc Things We Do For Love 10 Cc Wall Street Shuffle 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years Wasteland 10, 000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs Because Of The Night 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal Because The Night 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping 10Cc Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc I'm Not In Love 10Cc We Do For Love 112 Come See Me 112 Cupid 112 Dance With Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 112 Peaches & Cream 112 Peaches And Cream 112 U Already Know 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Stones We Are One 19 Somethin' Mark Wills 1910 Fruitgum Co 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1,2,3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1975 Chocolate 1975 City 1975 Sex... 1975 Sex.... 1975, The Chocolate Song List Generator® Printed 7/23/2014 Page 1 of 661 Licensed to Greg Reil Karaoke List Songs by Artist Artist Title 1975, The Sex 1975, The The City 1Barenaked Ladies Be My Yoko Ono 1Barenaked Ladies Brian Wilson (2000 Version) 1Barenaked Ladies Call And Answer 1Barenaked Ladies Enid 1Barenaked Ladies Get In Line (Duet Version) 1Barenaked Ladies Get In Line (Solo Version) 1Barenaked Ladies It's All Been Done 1Barenaked Ladies Jane 1Barenaked Ladies Never Is Enough 1Barenaked Ladies Old Apartment, The 1Barenaked Ladies One Week 1Barenaked Ladies Shoe Box 1Barenaked Ladies Straw Hat 1Barenaked Ladies What A Good Boy 1Barenaked Ladies When I Fall 1Beatles, The Come Together 1Beatles, The Day Tripper 1Beatles, The Good Day Sunshine 1Beatles, The Help! 1Beatles, The I Saw Her Standing There 1Beatles, The Love Me Do 1Beatles, The Nowhere Man 1Beatles, The P.S. -

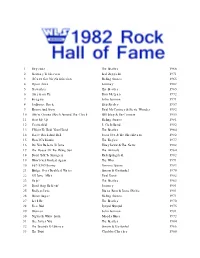

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud