H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of a Free Press in Prerevolutionary Virginia: Creating

Dedication To my late father, Curtis Gordon Mellen, who taught me that who we are is not decided by the advantages or tragedies that are thrown our way, but rather by how we deal with them. Table of Contents Foreword by David Waldstreicher....................................................................................i Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................iii Chapter 1 Prologue: Culture of Deference ...................................................................................1 Chapter 2 Print Culture in the Early Chesapeake Region...........................................................13 A Limited Print Culture.........................................................................................14 Print Culture Broadens ...........................................................................................28 Chapter 3 Chesapeake Newspapers and Expanding Civic Discourse, 1728-1764.......................57 Early Newspaper Form...........................................................................................58 Changes: Discourse Increases and Broadens ..............................................................76 Chapter 4 The Colonial Chesapeake Almanac: Revolutionary “Agent of Change” ...................97 The “Almanacks”.....................................................................................................99 Chapter 5 Women, Print, and Discourse .................................................................................133 -

TRADITIONS of WAR This Page Intentionally Left Blank Traditions of War

TRADITIONS OF WAR This page intentionally left blank Traditions of War OCCUPATION, RESISTANCE, AND THE LAW KARMA NABULSI 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Karma Nabulsi 1999 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 1999 First published in paperback 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Nabulsi, Karma. -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Sarah C. Maza Curriculum Vitae Education: Employment

1 Sarah C. Maza Curriculum Vitae Department of History, Harris Hall Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, 60208-2220 Office: 847 491 7033/3406 e-mail: [email protected] Education: Princeton University, M.A.in History, 1975; Ph.D. in History, 1978 Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, France, Licence-ès-Lettres, 1973 Employment: Director, Nicholas D. Chabraja Center for Historical Studies, Northwestern University, 2012-2015, 2016-2019. Jane Long Professor in the Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University, 1998- Chair, Department of History, Northwestern University, 2001-2004, 2008-09; Associate Chair, 2016-17. Professor, Northwestern University, 1990- Directeur d'Études Associé, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, Spring 1988 and Spring 2011 Associate Professor, Northwestern University, 1984-1990 Assistant Professor, Northwestern University, 1978-1984 Major Prizes and Honors: Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2013- 2 President, American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2005-2006. 2004 George Mosse Prize of the American Historical Association for The Myth of the French Bourgeoisie. 1997 Chester Higby Prize of the American Historical Association for “Luxury, Morality and Social Change,” Journal of Modern History 1993 David Pinkney Prize of the Society for French Historical Studies for Private Lives and Public Affairs Grants and Fellowships: Rockefeller Center in Bellagio Writing Residency for Scholars, November 2019 Dorothy and Clarence Ver Steeg Distinguished Research Fellowship, Northwestern -

Thomson, Graeme M. (2014) Heirs of the Revolution: the Founding Heritage in American Presidential Rhetoric Since 1945

Thomson, Graeme M. (2014) Heirs of the revolution: the founding heritage in American presidential rhetoric since 1945. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5103/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Heirs of the Revolution: The Founding Heritage in American Presidential Rhetoric Since 1945 Graeme Michael Thomson MA MLitt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow October 2013 2 Abstract The history of the United States’ revolutionary origins has been a persistently prevalent source of reference in the public speeches of modern American presidents. Through an examination of the character and context of allusions to this history in presidential rhetoric since 1945, this thesis presents an explanation for this ubiquity. America’s founding heritage represents a valuable – indeed, an essential – source for the purposes of presidential oratory. An analysis of the manner in which presidents from Harry Truman to Barack Obama have invoked and adapted specific aspects of this heritage in their public rhetoric exposes a distinctly usable past, employed in different contexts and in advancing specific messages. -

Andrew J. Bacevich

ANDREW J. BACEVICH Department of International Relations Boston University 152 Bay State Road Boston, Massachusetts 02215 Telephone (617) 358-0194 email: [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Boston University Professor of History and International Relations, College of Arts & Sciences Professor, Kilachand Honors College EDUCATION Princeton University, M. A., American History, 1977; Ph.D. American Diplomatic History, 1982 United States Military Academy, West Point, B.S., 1969 FELLOWSHIPS Columbia University, George McGovern Fellow, 2014 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame Visiting Research Fellow, 2012 The American Academy in Berlin Berlin Prize Fellow, 2004 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Visiting Fellow of Strategic Studies, 1992-1993 The John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University National Security Fellow, 1987-1988 Council on Foreign Relations, New York International Affairs Fellow, 1984-1985 PREVIOUS APPOINTMENTS Boston University Director, Center for International Relations, 1998-2005 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer; Executive Director, Foreign Policy Institute, 1993-1998 School of Arts and Sciences, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer, Department of Political Science, 1995-19 United States Military Academy, West Point Assistant Professor, Department of History, 1977-1980 1 PUBLICATIONS Books and Monographs Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country. New York: Metropolitan Books (2013); audio edition (2013). The Short American Century: A Postmortem. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (2012). (editor) Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War. New York: Metropolitan Books (2010); audio edition (2010); Chinese edition (2011); Korean edition (2013). The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism. -

THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY of JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU the Impossibilityof Reason

qvortrup.cov 2/9/03 12:29 pm Page 1 Was Rousseau – the great theorist of the French Revolution – really a Conservative? THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY OF JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU This original study argues that the author of The Social Contract was a constitutionalist much closer to Madison, Montesquieu and Locke than to revolutionaries. Outlining his profound opposition to Godless materialism and revolutionary change, this book finds parallels between Rousseau and Burke, as well as showing that Rousseau developed the first modern theory of nationalism. The book presents an inte- grated political analysis of Rousseau’s educational, ethical, religious and political writings. The book will be essential readings for students of politics, philosophy and the history of ideas. ‘No society can survive without mutuality. Dr Qvortrup’s book shows that rights and responsibilities go hand in hand. It is an excellent primer for any- one wishing to understand how renewal of democracy hinges on a strong civil society’ The Rt. Hon. David Blunkett, MP ‘Rousseau has often been singled out as a precursor of totalitarian thought. Dr Qvortrup argues persuasively that Rousseau was nothing of the sort. Through an array of chapters the book gives an insightful account of Rousseau’s contribution to modern philosophy, and how he inspired individuals as diverse as Mozart, Tolstoi, Goethe, and Kant’ John Grey, Professor of European Political Thought,LSE ‘Qvortrup has written a highly readable and original book on Rousseau. He approaches the subject of Rousseau’s social and political philosophy with an attractively broad vision of Rousseau’s thought in the context of the development of modernity, including our contemporary concerns. -

Britain and Corsica 1728-1796: Political Intervention and the Myth of Liberty

BRITAIN AND CORSICA 1728-1796: POLITICAL INTERVENTION AND THE MYTH OF LIBERTY Luke Paul Long A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13232 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence Britain and Corsica 1728-1796: Political intervention and the myth of liberty Luke Paul Long This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews September 2017 1 Contents Declarations…………………………………………………………………………….5 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………7 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….8 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………...9 Chapter 1: Britain and Corsica: the development of British opinion and policy on Corsica, 1728-1768 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………24 Historiographical debates surrounding Britain and Corsica…………………………..25 History of Corsica and Genoa up until 1720………………………………………….29 The History of Corsica 1730-1748- first British involvement………………………..31 Rousseau and Paoli: the growth in the ‘popularity’ of the Corsican cause…………...37 Catherine Macaulay’s A short sketch of a democratical form of government (1767)...45 James Boswell and his Account of Corsica (1768)…………………………………...51 Journal of a tour to that island and memoirs of Pascal Paoli…………………………...58 Conclusion: Rousseau -

Curriculum Vitae of Linda Colley

LINDA COLLEY PROFESSIONAL ADDRESS: Department of History, Princeton University, 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ. 08544. Tel: (001) 609-258-8076 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.lindacolley.com 1. UNIVERSITY CAREER: 2003-: Princeton University: Shelby M.C. Davis 1958 Professor of History 1998-2003: London School of Economics: Leverhulme Senior Research Professor and University Professor in History 1982-98: Yale University: 1998: Sterling [University] Professorship offered. Declined so as to accept LSE position. 1992-98: Richard M. Colgate Professor of History 1990-92: Professor of History 1985-90: Tenured Associate Professor of History 1982-85: Assistant Professor of History 1972-82: Cambridge University: 1979-82: Fellow and Lecturer in History, Christ’s College. 1978-9: Joint Lectureship in History, King’s and Newnham Colleges 1977: Ph.D. Degree: “The Tory Party 1727-1760” 1975-78: Eugenie Strong Research Fellowship, Girton College 1975: M.A. Degree 1972-75: Graduate research in history at Darwin College 1969-72: Bristol University: 1972: First class B.A. Honours degree in History 1972: George Hare Leonard Prize in History 1972: Graham Robertson Travelling Fellowship 1971: University Scholarship 1 2. PUBLICATIONS: a) Books Forthcoming: The Gun, The Ship and the Pen: War, Constitutions and the Making of the Modern World, to be published by Norton in March 2021 Acts of Union and Disunion, Profile Books, 2014, pp. 188. Now in its third printing, this is an expanded version of fifteen talks I was commissioned to write and deliver for BBC Radio 4 in January 2014, to provide historical background for members of the British public on the formation and divisions of the UK in readiness for the referendum that year on Scottish independence and for the referendum on withdrawal from the European Union, and to situate the making of the UK over time in wider international contexts. -

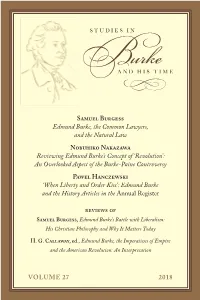

Studies in Burke and His Time, Volume 23

STUDIES IN BURKE AND HIS TIME AND HIS STUDIES IN BURKE I N THE N EXT I SS UE ... S TEVEN P. M ILLIE S STUDIES IN The Inner Light of Edmund Burke A N D REA R A D A S ANU Edmund Burke’s Anti-Rational Conservatism R O B ERT H . B ELL The Sentimental Romances of Lawrence Sterne AND HIS TIME J.D. C . C LARK A Rejoinder to Reviews of Clark’s Edition of Burke’s Reflections R EVIEW S O F M ICHAEL B ROWN The Meal at the Saracen’s Head: Edmund Burke F . P. L OCK Edmund Burke Volume II: 1784 – 1797 , andSamuel the Scottish Burgess Literati S EAN P ATRICK D ONLAN , Edmund Burke’s Irish Identities Edmund Burke, the Common Lawyers, M ICHAEL F UNK D ECKAR D and the Natural Law N EIL M C A RTHUR , David Hume’s Political Theory Wonder and Beauty in Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry E LIZA B ETH L A MB ERT , Edmund Burke of Beaconsfield NobuhikoR O B ERT HNakazawa. B ELL FoolReviewing for Love: EdmundThe Sentimental Burke’s Romances Concept of ofLaurence ‘Revolution’: Sterne An Overlooked AspectS TEVEN of theP. MBurke-PaineILLIE S Controversy The Inner Light of Edmund Burke: A Biographical Approach to Burke’s Religious Faith and Epistemology STUDIES IN Pawel Hanczewski ‘When Liberty and Order Kiss’: Edmund Burke VOLUME 22 2011 and the History Articles in the Annual Register REVIEWreviewsS OofF AND HIS TIME SamuelF.P. Burgess,LOCK, Edmund Edmund Burke: Burke’s Vol. Battle II, 1784–1797; with Liberalism: DANIEL I. -

Report of Contracting Activity

Vendor Name Address Vendor Contact Vendor Phone Email Address Total Amount 1213 U STREET LLC /T/A BEN'S 1213 U ST., NW WASHINGTON DC 20009 VIRGINIA ALI 202-667-909 $3,181.75 350 ROCKWOOD DRIVE SOUTHINGTON CT 13TH JUROR, LLC 6489 REGINALD F. ALLARD, JR. 860-621-1013 $7,675.00 1417 N STREET NWCOOPERATIVE 1417 N ST NW COOPERATIVE WASHINGTON DC 20005 SILVIA SALAZAR 202-412-3244 $156,751.68 1133 15TH STREET NW, 12TH FL12TH FLOOR 1776 CAMPUS, INC. WASHINGTON DC 20005 BRITTANY HEYD 703-597-5237 [email protected] $200,000.00 6230 3rd Street NWSuite 2 Washington DC 1919 Calvert Street LLC 20011 Cheryl Davis 202-722-7423 $1,740,577.50 4606 16TH STREET, NW WASHINGTON DC 19TH STREET BAPTIST CHRUCH 20011 ROBIN SMITH 202-829-2773 $3,200.00 2013 H ST NWSTE 300 WASHINGTON DC 2013 HOLDINGS, INC 20006 NANCY SOUTHERS 202-454-1220 $5,000.00 3900 MILITARY ROAD NW WASHINGTON DC 202 COMMUNICATIONS INC. 20015 MIKE HEFFNER 202-244-8700 [email protected] $31,169.00 1010 NW 52ND TERRACEPO BOX 8593 TOPEAK 20-20 CAPTIONING & REPORTING KS 66608 JEANETTE CHRISTIAN 785-286-2730 [email protected] $3,120.00 21C3 LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT LL 11 WATERFORD CIRCLE HAMPTON VA 23666 KIPP ROGERS 757-503-5559 [email protected] $9,500.00 1816 12TH STREET NW WASHINGTON DC 21ST CENTURY SCHOOL FUND 20009 MARY FILARDO 202-745-3745 [email protected] $303,200.00 1550 CATON CENTER DRIVE, 21ST CENTURY SECURITY, LLC #ADBA/PROSHRED SECURITY BALTIMORE MD C. MARTIN FISHER 410-242-9224 $14,326.25 22 Atlantic Street CoOp 22 Atlantic Street SE Washington DC 20032 LaVerne Grant 202-409-1813 $2,899,682.00 11701 BOWMAN GREEN DRIVE RESTON VA 2228 MLK LLC 20190 CHRIS GAELER 703-581-6109 $218,182.28 1651 Old Meadow RoadSuite 305 McLean VA 2321 4th Street LLC 22102 Jim Edmondson 703-893-303 $13,612,478.00 722 12TH STREET NWFLOOR 3 WASHINGTON 270 STRATEGIES INC DC 20005 LENORA HANKS 312-618-1614 [email protected] $60,000.00 2ND LOGIC, LLC 10405 OVERGATE PLACE POTOMAC MD 20854 REZA SAFAMEJAD 202-827-7420 [email protected] $58,500.00 3119 Martin Luther King Jr. -

H-France Review Volume 16 (2016) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 16 (2016) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 16 (October 2016), No. 245 David A. Bell, Shadows of Revolution: Reflections on France, Past and Present. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. Xii + 444 pp. Illustrations and Index. $29.95 U.S. (cl). ISBN 978-0-19- 026268-6. Review by Lloyd Kramer, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. David Bell has been an influential contributor to recent scholarship on the history of old regime French lawyers, the emergence of French nationalism, the development of Napoleonic-era “total war,” and the meaning of Napoleon’s life and actions.[1] This important work has established his reputation for careful research and for insightful, analytical overviews of major historical issues. This new book, however, offers a very different kind of historical writing. Shadows of Revolution: Reflections on France, Past and Present consists almost entirely of book reviews and historical commentaries that he has written for nonacademic magazines and newspapers over the last twenty-five years. This collection thus sets aside the usual infrastructure of historical scholarship (there are no footnotes, bibliography, or archival sources), yet it conveys a remarkable range of historical knowledge. Dispensing with the footnoted research of academic writing, Bell describes his fascination with France, his critical-minded engagement with complex cultural issues, and his belief that modern French history remains an important subject for readers who live in other nations and also live happily without ever reading historical scholarship. “Public intellectual” is the common, amorphous term for authors who write regularly for public audiences.