(2015), Volume 3, Issue 7, 1538-1544

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Minority Media and Community Agenda Setting a Study on Muslim Press in Kerala

Minority Media and Community Agenda Setting A Study On Muslim Press In Kerala Muhammadali Nelliyullathil, Ph.D. Dean, Faculty of Journalism and Head, Dept. of Mass Communication University of Calicut, Kerala India Abstract Unlike their counterparts elsewhere in the country, Muslim newspapers in Kerala are highly professional in staffing, payment, and news management and production technology and they enjoy 35 percent of the newspaper readership in Kerala. They are published in Malayalam when Indian Muslim Press outside Kerala concentrates on Urdu journalism. And, most of these newspapers have a promising newsroom diversity employing Muslim and non-Muslim women, Dalits and professionals from minority and majority religions. However, how effective are these newspapers in forming public opinion among community members and setting agendas for community issues in public sphere? The study, which is centered on this fundamental question and based on the conceptual framework of agenda setting theory and functional perspective of minority media, examines the role of Muslim newspapers in Kerala in forming a politically vibrant, progress oriented, Muslim community in Kerala, bringing a collective Muslim public opinion into being, Influencing non-Muslim media programming on Muslim issues and influencing the policy agenda of the Government on Muslim issues. The results provide empirical evidences to support the fact that news selection and presentation preferences and strategies of Muslim newspapers in Kerala are in line with Muslim communities’ news consumption pattern and related dynamics. Similarly, Muslim public’s perception of community issues are formed in accordance with the news framing and priming by Muslim newspapers in Kerala. The findings trigger more justifications for micro level analysis of the functioning of the Muslim press in Kerala to explore the community variable in agenda setting schema and the significance of minority press in democratic political context. -

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

Reporting Techniques & Skills

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Reporting Techniques & Skills Study Material for Students 1 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Reporting Techniques & Skills CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman, producer, director, etc. Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping : Reporting Techniques & Skills INTRODUCTION The book deals with techniques of reporting. The students will learn the skills of gathering news and reporter’s art of writing the news. The book explains the basic formula of writing the news and the kinds of leads. Students will also learn different types of reporting and the importance of clarity and accuracy in writing news. -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

RLI-Electronic Insurance Coverage Report-Kerala

RELIANCE LIFE INSURANCE TIES UP WITH INSURANCE REPOSITORIES TO OFFER ELECTRONIC INSURANCE POLICIES MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT KERALA COVERAGE SYNOPSIS RLI-ELECTRONIC INSURANCE POLICIES COVERAGE DETAILS KOCHI S.No. Publications Language Circulation Date 1. Deccan Chronicle English 35000 28/11/2013 2. HBL English 25000 02/12/2013 3. HBL English 25000 02/12/2013 4. HBL English 25000 04/12/2013 5. Financial Express English 12000 28/11/2013 6. Malayala Manorama Malayalam 305600 06/12/2013 7. Matrubhoomi Malayalam 145698 05/12/2013 8. Veekshanam Malayalam 38454 03/12/2013 9. Deshabhimaani Malayalam 41677 08/12/2013 10. Chandrika Malayalam 42708 03/12/2013 11. Vaarthamanam Malayalam 35000 05/12/2013 12. Siraj Malayalam 25456 08/12/2013 13. Kerala Kaumudi Malayalam 22836 03/12/2013 14. Metro Vaartha Malayalam 75000 14/12/2013 TOTAL 854429 KOCHI MEDIA COVERAGE Publication Deccan Chronicle Date 28th November, 2013 Page No 12 Edition Kochi Headline RLIC TIES UP WITH REPOSITORIES Publication Hindu Business Line Date 2nd December, 2013 Page No 01 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH REPOSITORIES Publication Hindu Business Line Date 2nd December, 2013 Page No 05 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH INSURANCE REPOSITORIES Publication Hindu Business Line Date 4th December, 2013 Page No 17 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH INSURANCE REPOSITORIES Publication The Financial Express Date 28th November, 2013 Page No 08 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH FIVE INSURANCE REPOSITORIES Publication Malayala Manorama -

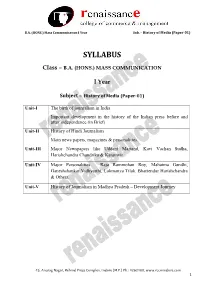

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

Government Advertising As an Indicator of Media Bias in India

Sciences Po Paris Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India by Prateek Sibal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master in Public Policy under the guidance of Prof. Julia Cage Department of Economics May 2018 Declaration of Authorship I, Prateek Sibal, declare that this thesis titled, 'Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for Masters in Public Policy at Sciences Po, Paris. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Signed: Date: iii Abstract by Prateek Sibal School of Public Affairs Sciences Po Paris Freedom of the press is inextricably linked to the economics of news media busi- ness. Many media organizations rely on advertisements as their main source of revenue, making them vulnerable to interference from advertisers. In India, the Government is a major advertiser in newspapers. Interviews with journalists sug- gest that governments in India actively interfere in working of the press, through both economic blackmail and misuse of regulation. However, it is difficult to gauge the media bias that results due to government pressure. This paper determines a newspaper's bias based on the change in advertising spend share per newspa- per before and after 2014 general election. -

List of Environment Columnist

List of Environment Columnist Name Organisation E-mail Ben Anthony South Asia bureau chief, Christian [email protected] Science Monitor, Delhi Chetan Chauhan Assistant editor-environment, The chetan@hindustantimes Hindustan Times, Delhi .com Jaideep Hardikar Special correspondent, DNA, Nagpur, jaideep.hardikar@gmail. Maharashtra com Urmi Goswami Special correspondent, The Economic [email protected] Times, Delhi, m Nitin Sethi Assistant editor-national bureau, The [email protected] Times of India, Delhi, Minakshi Arora Chairperson and coordinator, India water.community@gmai Water Portal, Delhi, l.com Richa Malhotra Science writer, Current Science, [email protected] Bangalore, Karnataka, Jupinderjit Singh Bureau chief, The Tribune, Jammu, [email protected] J&K Sunita Narayan Writes for Business Standard, [email protected] www.indiatogether.org , and Down to www.indiatogether.org , Earth. Director General of CSE Varun Dutt Financial Chronicle, Faculty of Carneqie Mellon University Darryl D’Monte DNA, Outlook Magazine, [email protected] www.indiatogether.org and m www.infochangeindia.org , is Chairperson of the Forum of Environmental Journalists of India Savita Hiremath Writes for New Indian Express and [email protected] www.indiatogether.org , independent journalist based in Bangalore. Dr. Sujatha Byravan Writes for The Indian Express, and [email protected] www.indiatogether.org . Based in Chennai, she is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Development Finance in IFMR P N Venugopal writes for http://questfeatures.org/ , [email protected] Down to Earth, The Hindu, m www.indiatogether.org and is independent journalist based in Kochi, Kerala. Kanchi Kohli writes for the Sunday-Guardian and [email protected] www.indiatogether.org . -

Prospectus-2020

JOURNALISM DEPARTMENT WITH A DIFFERENCE The Institute of Communication and Journalism (ICJ) was founded in 1995 to provide best-in- class Journalism and Mass Communication education, in the Self-Financing Stream directly under the Mahatma Gandhi University. Over the past 25 years, the ICJ rose to the ranks of the most sought-after media management course, moulding high quality media professionals. With its unique design of the course which focuses on honing practical skills and delving deep into each subject on a theoretical level, contemporary application of knowledge and analysis, the MAJMC course equips the students to pursue Journalism careers across the media spectrum. The ICJ was proudly considered the flagship Department of the MG University since its founding. The design is underpinned by strong industry support and knowledge brought in by a formidable range of advisors and professionals from the media, and faculty with rich working experience in the field. Apart from the state-of-the-art facilities in broadcasting, telecasting, video production, print media and web-journalism training, we are also developing a unique innovative approach to the enterprise and media management in the creative industry. The full-time P.G course, the Master of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication (MAJMC), offered by the MG University in 4 Semesters through our Department is designed for students wishing to pursue Journalism careers at a high level of engagement. Practical oriented coaching is our strength. For enhanced visibility and performance standards for key job-oriented Departments, under the initiative of the M.G University, the Centre for Professional and Advanced Studies – CPAS was established by the Government of Kerala. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Palakkad PALAKKAD

Palakkad PALAKKAD / / / s Category in s s e e Final e Y which Y Reason for Y ( ( ( Decision in 9 his/her 9 Final 9 1 1 appeal 1 - - house is - Decision 6 3 1 - - (Increased - 0 included in 1 (Recommen 1 3 3 relief 3 ) ) ) Sl Name of disaster Ration Card the Rebuild ded by the Relief Assistance e e o o o e r Taluk Village r amount/Red r N N N o No. affected Number App ( If not o Technically Paid or Not Paid o f f f uced relief e e in the e Competent b b b amount/No d Rebuild App d Authority/A d e e e l l change in a Database fill a ny other m e e i relief p p the column a reason) l p p amount) C A as `Nil' ) A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 Palakkad Akathethara T M SURENDREN 1946162682 yes Paid 2 Palakkad Akathethara DEVU 1946022862 yes Paid 3 Palakkad Akathethara PRASAD K 1946022923 yes Paid 4 Palakkad Akathethara MANIYAPPAN R 1946022878 yes Paid 5 Palakkad Akathethara SHOBHANA P 1946021881 yes Paid Not Paid 6 Palakkad Akathethara Seetha 1946022739 yes Duplication 7 Palakkad Akathethara SEETHA 1946022739 yes Paid 8 Palakkad Akathethara KRISHNAVENI K 1946158835 yes Paid 9 Palakkad Akathethara kamalam 1946022988 yes Paid 10 Palakkad Akathethara PRIYA R 1946132777 yes Paid 11 Palakkad Akathethara CHELLAMMA 1946022421 yes Paid Page 1 Palakkad 12 Palakkad Akathethara Chandrika k 1946022576 yes Paid 13 Palakkad Akathethara RAJANI C 1946134568 yes Paid KRISHNAMOORT 14 Palakkad Akathethara 1946022713 yes Paid HY N 15 Palakkad Akathethara Prema 1946023035 yes Paid 16 Palakkad Akathethara PUSHPALATHA 1946022763 yes Paid 17 Palakkad Akathethara KANNAMMA