Ten Years in Afghanistan's Pech Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Updated 02.03.2021 an Annotated List of Afghanistan Longhorn Beetles

Updated 02.03.2021 An annotated list of Afghanistan Longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) M.A. Lazarev The list is based on the publication by M. A. Lazarev, 2019: Catalogue of Afghanistan Longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) with two descriptions of new Phytoecia (Parobereina Danilevsky, 2018) from Central Asia. - Humanity space. International almanac, 8 (2): 104-140.It is regularly updated as new taxa are described (marked with red). Family CERAMBYCIDAE Latreille, 1802 subfamily Prioninae Latreille, 1802 tribe Macrotomini J. Thomson, 1861 genus Anomophysis Quentin & Villiers, 1981: 374 type species Prionus spinosus Fabricius, 1787 inscripta C.O. Waterhouse, 1884: 380 (Macrotoma) Heyrovský, 1936: 211 - Wama; Tippmann, 1958: 41 - Kabul, Ost-Afghanistan, 1740; Sarobi, am Kabulflus, 900 m; Mangul, Bashgultal, Nuristan, Ost-Afghanistan, 1250 m; Fuchs, 1961: 259 - Sarobi 1100 m, O.- Afghanistan; Fuchs, 1967: 432 - Afghanistan, 25 km N von Barikot, 1800 m, Nuristan; Nimla, 40 km SW von Dschelalabad; Heyrovský, 1967: 156 - Zentral-Afghanistan, Prov. Kabul: Kabul; Kabul-Zahir; Ost- Afghanistan, Prov. Nengrahar: “Nuristan”, ohne näheren Fundort; Kamu; Löbl & Smetana, 2010: 90 - Afghanistan. plagiata C.O. Waterhouse, 1884: 381 (Macrotoma) vidua Lameere, 1903: 167 (Macrotoma) Quentin & Villiers, 1981: 361, 376, 383 - Afghanistan: Kaboul; Sairobi; Darah-i-Nour, Nangahar; Löbl & Smetana, 2010: 90 - Afghanistan; Kariyanna et al., 2017: 267 - Afghanistan: Kaboul; Rapuzzi et al., 2019: 64 - Afghanistan. tribe Prionini Latreille, 1802 genus Dorysthenes Vigors, 1826: 514 type species Prionus rostratus Fabricius, 1793 subgenus Lophosternus Guérin-Méneville, 1844: 209 type species Lophosternus buquetii Guérin- Méneville, 1844 Cyrtosternus Guérin-Méneville, 1844: 210 type species Lophosternus hopei Guérin-Méneville, 1844 huegelii L. Redtenbacher, 1844: 550 (Cyrtognathus) falco J. -

26 August 2010

SIOC – Afghanistan: UNITED NATIONS CONFIDENTIAL UN Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan Security Situation Report, Week 34, 20 – 26 August 2010 JOINT WEEKLY SECURITY ANALYSIS Countrywide security incidents continued to increase compared to the previous week with the NER, NR, SR and SER, recording higher levels of security incidents. In the ER a minor downward trend continues to be observed over the last three weeks, in the WR and CR records dropped. The dynamics along the south and south-eastern belt of the country vary again with the SR reasserting as the most volatile area. Security incidents were more widespread countrywide with the following provinces being the focus of the week: Kunduz, Baghlan in the NER; Faryab in the NR, Hirat in the WR, Kandahar and Helmand in the SR; Ghazni and Paktika in the SER and Kunar in the ER. Overall the majority of the incidents are initiated by insurgents and those related to armed conflict – armed clashes, IED attacks and stand off attacks - continue to account for the bulk of incidents. Reports of insurgents’ infiltration, re-supply and propaganda are recorded in the NR, SR, SER, ER and CR. These reports might corroborate assumptions that insurgents would profit from the Ramadan time to build up for an escalation into the election and pre-election days. The end of the week was dominated by the reporting of the violent demonstration against the IM base in Qala-i-Naw city following a shoot out at the entrance of the base. Potential for manipulation by the local Taliban and the vicinity of the UN compound to the affected area raised concerns on the security of the UN staff and resulted in the evacuation of the UN building. -

21St-Century Agriculture

21st-Century Agriculture U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE • BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL INFORMATION PROGRAMS The Bureau of International Information Programs of the U.S. Department of State publishes a monthly electronic journal under the eJournal USA logo. These journals examine major issues facing the United States and the international community, as well as U.S. society, values, thought, and institutions. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE / MARCH 2010 VOLUME 15 / NUMBER 3 One new journal is published monthly in English and is http://www.america.gov/publications/ejournalusa.html followed by versions in French, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. Selected editions also appear in Arabic, Chinese, and Persian. Each journal is catalogued by volume and International Information Programs: number. Coordinator Daniel Sreebny The opinions expressed in the journals do not necessarily Executive Editor Jonathan Margolis reflect the views or policies of the U.S. government. The Creative Director Michael Jay Friedman U.S. Department of State assumes no responsibility for the content and continued accessibility of Internet sites to which the journals link; such responsibility resides Editor-in-Chief Richard W. Huckaby solely with the publishers of those sites. Journal articles, Managing Editor Charlene Porter photographs, and illustrations may be reproduced and Web Producer Janine Perry translated outside the United States unless they carry Designer Chloe D. Ellis explicit copyright restrictions, in which case permission must be sought from the copyright holders noted in the journal. Copy Editor Jeanne Holden The Bureau of International Information Programs Photo Editor Maggie Johnson Sliker maintains current and back issues in several electronic Cover Design David Hamill formats, as well as a list of upcoming journals, at Reference Specialist Anita Green http://www.america.gov/publications/ejournals.html. -

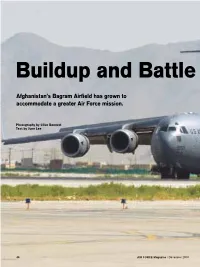

Buildup and Battle

Buildup and Battle Afghanistan’s Bagram Airfield has grown to accommodate a greater Air Force mission. Photography by Clive Bennett Text by June Lee 46 AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 Buildup and Battle A C-17 Globemaster III rolls to a stop on a Bagram runway after a resupply mission. Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, has been a hotspot for NATO and US operations in Southwest Asia and there are no signs of the pace letting up. AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 47 n Afghanistan, Bagram Airfield Ihosts several thousand airmen and other troops, deployed from all over the world. The 455th Air Expedition- ary Wing at Bagram provides air support to coalition and NATO Inter- national Security Assistance Forces on the ground. |1| The air traffic control tower is one of the busiest places on Bagram Airfield, with more than 100 movements taking place in a day. Civilian air traffic control- lers keep an eye on the runway and the skies above Afghanistan. |2| An F-15E from the 48th Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath, UK, taxis past revetments for the start of another mission. All F-15s over Afghanistan fly two-ship sorties. |3| A CH-47 Chinook from the Georgia Army National Guard undergoes line main- tenance by Army Spc. Cody Staley and Spc. Joe Dominguez (in the helicopter). 1 2 3 48 AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 1 22 3 4 5 |1| A1C Aaron Simonson gives F-16 C-17 at Bagram wait to be unloaded. EFS, Hill AFB, Utah, and the 79th pilot Capt. Nathan Harrold the ap- These mine-resistant ambush-pro- EFS, Shaw AFB, S.C. -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

Transregional Intoxications Wine in Buddhist Gandhara and Kafiristan

Borders Itineraries on the Edges of Iran edited by Stefano Pellò Transregional Intoxications Wine in Buddhist Gandhara and Kafiristan Max Klimburg (Universität Wien, Österreich) Abstract The essay deals with the wine culture of the Hindu Kush area, which is believed to be among the oldest vinicultural regions of the world. Important traces and testimonies can be found in the Gandharan Buddhist stone reliefs of the Swat valley as well as in the wine culture of former Kafiristan, present-day Nuristan, in Afghanistan, which is still in many ways preserved among the Kalash Kafirs of Pakistan’s Chitral District. Kalash represent a very interesting case of ‘pagan’ cultural survival within the Islamic world. Keywords Kafiristan. Wine. Gandhara. Kalash. Dionysus, the ancient wine deity of the Greeks, was believed to have origi- nated in Nysa, a place which was imagined to be located somewhere in Asia, thus possibly also in the southern outskirts of the Hindu Kush, where Alexander and his Army marched through in the year 327 BCE. That wood- ed mountainous region is credited by some scholars with the fame of one of the most important original sources of the viticulture, based on locally wild growing vines (see Neubauer 1974). Thus, conceivably, it was also the regional viniculture and not only the (reported) finding of much of ivy and laurel which had raised the Greeks’ hope to find the deity’s mythical birth place. When they came across a village with a name similar to Nysa, the question appeared to be solved, and the king declared Dionysus his and the army’s main protective deity instead of Heracles, thereby upgrading himself from a semi-divine to a fully divine personality. -

Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus

Country Policy and Information Note Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus Version 5.0 May 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

D.D.C. Apr. 20, 2007

Case 1:06-cv-01707-GK Document 20 Filed 04/20/2007 Page 1 of 22 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) RUZATULLAH, et al.,) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 06-CV-01707 (GK) ) ROBERT GATES, ) Secretary, United States Department of ) Defense, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) RESPONDENTS’ REPLY TO PETITIONERS’ REPLY AND OPPOSITION TO RESPONDENTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS THE SECOND AMENDED PETITION Respondents respectfully submit this reply brief in response to Petitioners’ Reply and Opposition to Respondents’ Motion to Dismiss the Second Amended Petition. In their opening brief, respondents demonstrated that this Court has no jurisdiction to hear the present habeas petition because the petition, filed by two alien enemy combatants detained at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan, falls squarely within the jurisdiction-limiting provision of the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (“MCA”), Pub. L. No. 109-366, 120 Stat. 2600 (2006). Respondents also demonstrated that petitioners do not have a constitutional right to habeas relief because under Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950), aliens detained abroad, such as petitioners, who have no significant voluntary connections with this country, cannot invoke protections under the Constitution. Subsequent to respondents’ motion to dismiss, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit decided Boumediene v. Bush, 476 F.3d 981 (D.C. Cir.), cert. denied, 127 S.Ct. 1478 (2007), which removes all doubt that the MCA divests federal courts of jurisdiction to review petitions for writs of habeas corpus filed by aliens captured abroad and detained as enemy Case 1:06-cv-01707-GK Document 20 Filed 04/20/2007 Page 2 of 22 combatants in an overseas military base. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Nuristan Province

Nuristan Province - Reference Map ! nm Qala ! Dahi Payan Main Shahr ! Lajaward Hassar Sang Awo Shahr ! Mokhawai u" ! Payen Dahi Bala Main Shahr Mokhawai ! Bala ! Khoram nm Legend ! Peow Dahi Zer nm ! ! Abrowi ! Seya Koh ! Irakh ! Dahan Royandara Rastawi ! Sele ! Etroye Posida ^! ! ! Bala Capital ! Espal Parwarda Kemyan ! ! Gawkush ! nm! ! Adaypas Dahan Zaytun !! ! Ab Pewa ! Provincial Center ! Hayot ! nm District Center Bam Now Shokho Sarlola ! ! Daha ! Sarower ! ! nm Zaran ! Dahi Jangalak ! Sawarq Khakhan ! ! ! Village Sarai Dasht nm nm Hazhdagher nmnm ! Administrative Boundaries Walf ! ! Koran wa Maghnawol Rabata Wulf Monjan ! ! Qala Robaghan ! !! ! International ! Tooghak Tagow Ayoum ! ! ! nm Sakazar nm nm Warsaj !u" ! Parwaz Yangi ! Paroch ! nm Dasht ! p Parghish Bot Province Razar ! ! PAKISTAN Yawi Yamak ! ! 36° N 36° Aylaqe nm T a k h a r Dara Dehe Tah Ab-anich Distirict ! Shaikh ! Pa'in Ghamand Milat ! ! Pastakan ! nm ! ! Kalt Shahran Khyber Dahi-taa Tal Payan ! Kandal Dahane Aw ! ! Dasht Pain Transportation ! ! Gar ! Meyan ! Pastkan ! Bala Keran Shahr nm (iskasik) Pakhtunkhwa Aska Sek Dahi Samanak Dahi Maina ! ! Amba Chashma Yesbokh ! ! Primary Road Dahi Bala Aylaqe Yesbokh ! Rawkan ! nm nm Chitral Secondary Road Welo ! nm nm nm ! Dewana Other Road Shah ! Ghaz ! ! Pari Baba Weshte nm nm nm u"! o Airport nm ! ! nm u" p Sar Airfield B a d a k h s h a n Jangal Khost Wa Atat So ! Meyan Dahi ! Fereng Pashawer Elevation (meter) Yaow ! River/Lake Ghadak Koran Wa Monjan ! ! Panam nm Peshawur ! ! nm nm River/Stream > 5000 ! Afzok Qala -

Självständigt Arbete (15 Hp)

Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Självständigt arbete (15 hp) Författare Program/Kurs Engström, Joel OP SA 18-21 Handledare Antal ord: 11986 Mariam Bjarnesen Beteckning Kurskod 1OP415 A LONE SEAL – WHAT FAILURE CAN TELL US. ABSTRACT: Special operations are conducted more than ever in modern warfare. Since the 1980s they have developed and grown in numbers. But with more attempts of operations and bigger numbers, comes failures. One of these failures is operation Red Wings where a unit of US Navy SEALs at- tempted a recognisance and raid operation in the Hindu Kush. The purpose of this paper was to see how that failure could be analysed from an existing theory of Special operations. This was to ensure that other failures can be avoided but mainly to understand what really happened on that mountain in 2005. The method used was a case study of a single case to give an answer with quality and depth. The study found that Mcravens theory and principles of how to succeed a special operation was not applied during the operation. The case of operation Red Wings showed remarkable valour and motivation, but also lacked severely when it came to simplicity, surprise, and speed. Nyckelord: T.ex.: Specialoperationer, McRaven, Operation Red Wings, Specialförband. Sida 1 av 41 Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Innehållsförteckning 1. INLEDNING ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 PROBLEMFORMULERING ..............................................................................................................