The Catholic Concept of Revelation Since Vatican Ii and Its Impact on the Christian View of the ‘Other’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAG. 3 / Attualita Ta Grave Questione Del Successore Di Papa Giovanni Roma

FUnitd / giovedi 6 giugno 1963 PAG. 3 / attualita ta grave questione del successore di Papa Giovanni Roma il nuovo ILDEBRANDO ANTONIUTTI — d Spellman. E' considerate un • ron- zione statunltense dl Budapest dopo ITALIA Cardinale di curia. E' ritenuto un, calliano ». - --_., ^ <. la sua partecipazione alia rivolta del • moderate*, anche se intlmo di Ot 1956 contro il regime popolare. Non CLEMENTE MICARA — Cardinale taviani. E' nato a Nimis (Udine) ALBERT MEYER — Arcivescovo si sa se verra at Conclave. Sono not) di curia, Gran Cancelliere dell'Uni- nel 1898.' Per molti anni nunzio a d) Chicago. E' nato a Milxankee nel 1903. Membro di varie congregaziont. i recenti sondaggl della Santa Sede verslta lateranense. E* nato a Fra- Madrid; sostenuto dai cardinal! spa- per risotvere il suo caso. ficati nel 1879. Noto come • conserva- gnoli. JAMES MC. INTYRE — Arclve- tore >; ha perso molta dell'influenza EFREM FORNI — Cardinale di scovo di Los Angeles. E' nato a New che aveva sotto Pic XII. E' grave. York net 1886. Membro della con mente malato. , curia. E' nato a Milano net 1889. E' OLANDA stato nominate nel 1962. gregazione conclstoriale. GIUSEPPE PIZZARDO — Cardina JOSEPH RITTER — Arcivescovo BERNARD ALFRINK — Arcivesco le di curia, Prefetto delta Congrega- '« ALBERTO DI JORIO — Cardinale vo di Utrecht. Nato a Nljkeik nel di curia. E' nato a Roma nel 1884. di Saint Louis. E' nato a New Al zione dei seminar). E' nato a Savona bany nel 1892. 1900. Figura di punta degli innovator! nel 1877. SI e sempre situate all'estre. Fu segretario nel Conclave del 1958. sia nella rivendicazione dell'autono- ma destra anche nella Curia romana. -

137-144 Szuromi 12/10/12 1:39 PM Page 137

137-144 Szuromi 12/10/12 1:39 PM Page 137 SZUROMI SZABOLCS ANZELM O.Praem. A katolikus papság ókeresztény sajátosságai és ezek hatása a középkori (IX–XII. század) papképzés formáira* I. A DIAKÓNUS–PRESBITER–PÜSPÖK HIERARCHIKUS RENDSZERÉNEK I. LÉPÉSRÔL LÉPÉSRE TÖRTÉNÔ KIALAKULÁSA Az újszövetségi papság nem vezethetô le más, még a levitikus papság formájából sem, hi- szen ez a feladatkör pap-Jézus Krisztus szolgálatára épül, amiben egyúttal Ô maga az áldo- zat is. Ez a szolgálat folytatódik az apostoli hivatásban, amely hivatalokra tagolódva jele- nik meg a papi ordón belül, és amelynek minden fokozata függ az apostoli szolgálattól.1 Ha megvizsgáljuk a IV–V. századtól a XI. századig terjedô kánonjogi forrásokat, lát- hatjuk a diakónus, pap és püspök klerikusi fokozatokra vonatkozó elôírások lépésrôl lé- pésre történô letisztázódását2, valamint a püspök sajátos kormányzati, tanítói és megszen- telôi hatalmának meghatározó jellegét.3 A Canones Apostolici4 vagy más néven 85 apostoli kánon (IV. század vége)5 és a Statuta Ecclesiae Antiqua (476–485)6 szövegébôl egyértelmûen kitûnik, hogy a korai idôszakban a szent rend egyes fokozataihoz kötôdô sajátosságok még nem kerültek egyértelmû meghatározásra. Sôt, amennyiben megvizsgáljuk az egy- házatyák által ugyanezen idôszakban íródott forrásokat, világosan kitûnik, hogy azok sem tartalmaznak világos meghatározást a szent rend egyes fokozatainak egyedi sajátosságára vonatkozóan. Még a késôbbi – azaz pl. a XI. századi gregoriánus kánongyûjteményekben is – tisztán kivehetô az eredeti forrásoknak ez a tulajdonsága. Ezekben a munkákban el- sôdlegesen Szent Ciprián (†258), Szent Ambrus (†397), Szent Jeromos (†419/420), és Szent Ágoston (†430) írásainak részleteit olvashatjuk.7 A legfontosabb teológiai (ekklézio- * Elhangzott Rómában 2012. március 16-án. -

Antichrist Conspiracy Inside the Devil’S Lair

Antichrist Conspiracy Inside the Devil’s Lair Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing? The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD, and against his anointed, saying, Let us break their bands asunder, and cast away their cords from us. He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh: the Lord shall have them in derision. (Psalms 2:1-4 AV) Revised Fourteenth Edition Copyright © 1999, 2005 by Edward Hendrie The author hereby grants a limited license to copy and disseminate this book in whole or in part, provided that there is no material alteration to the text and any excerpts identify the book and give notice that they are excerpts from the larger work. All other rights are reserved. All Scripture references are to the Authorized (King James) Version of the Holy Bible, unless otherwise indicated. Email: ed[at]antichristconspiracy[dot]com (My email address is written that way in order to defeat spam spiders from obtaining the address online and sending out spam email to the address. To email me simply replace the [at] with @ and the [dot] with .) Web site: http://www.antichristconspiracy.com “To the only wise God our Saviour, be glory and majesty, dominion and power, both now and ever. Amen.” Jude 1:25. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................1 1. Conspiracy.............................................................2 2. Satan’s Religion.........................................................5 3. God’s Word............................................................6 4. Creation and Salvation Through God’s Word..................................8 5. God Preserves His Word..................................................8 6. The Roman Catholic Attack on God’s Word...................................9 7. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Vatican II Sect Vs. the Catholic Church on Non-Catholics Receiving Holy Communion

239 19. The Vatican II sect vs. the Catholic Church on non-Catholics receiving Holy Communion Pope Pius VIII, Traditi Humilitati (# 4), May 24, 1829: “Jerome used to say it this way: he who eats the Lamb outside this house will perish as did those during the flood who were not with Noah in the 1 ark.” Benedict XVI giving Communion to the public heretic, Bro. Roger Schutz,2 the Protestant founder of Taize on April 8, 2005 In the preceding sections on the heresies of Vatican II and John Paul II, we covered that they both teach the heresy that non-Catholics may lawfully receive Holy Communion. It’s important to summarize the Vatican II sect’s official endorsement of this heretical teaching here for handy reference: Vatican II Vatican II document, Orientalium Ecclesiarum # 27: “Given the above-mentioned principles, the sacraments of Penance, Holy Eucharist, and the anointing of the sick may be conferred on eastern Christians who in good faith are separated from the Catholic Church, if they make the request of their own accord and are properly disposed.”3 Non-Catholics receiving Communion 240 Paul VI solemnly confirming Vatican II Antipope Paul VI, at the end of every Vatican II document: “EACH AND EVERY ONE OF THE THINGS SET FORTH IN THIS DECREE HAS WON THE CONSENT OF THE FATHERS. WE, TOO, BY THE APOSTOLIC AUTHORITY CONFERRED ON US BY CHRIST, JOIN WITH THE VENERABLE FATHERS IN APPROVING, DECREEING, AND ESTABLISHING THESE THINGS IN THE HOLY SPIRIT, AND WE DIRECT THAT WHAT HAS THUS BEEN ENACTED IN SYNOD BE PUBLISHED TO GOD’S GLORY.. -

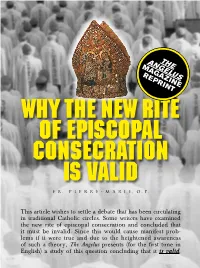

Why the New Rite of Episcopal Consecration Is Valid Fr

ANGELUSTHE MAGAZINE REPRINT WHY THE NEW RITE OF EPISCOPAL CONSECRATION IS VALID Fr. Pierre-Marie, O.P. This article wishes to settle a debate that has been circulating in traditional Catholic circles. Some writers have examined the new rite of episcopal consecration and concluded that it must be invalid. Since this would cause manifest prob- lems if it were true and due to the heightened awareness of such a theory, The Angelus presents (for the first time in English) a study of this question concluding that it is valid. 2 This article was translated exclusively by Angelus Press from Sel de la Terre (No.54., Autumn 2005, pp.72-129). Fr. Pierre-Marie, O.P., is a member of the traditional Dominican monastery at Avrillé, France, several of whose members were ordained by Archbishop Lefebvre and which continues to receive its priestly ordinations from the bishops serving the Society of Saint Pius X which Archbishop Lefebvre founded. He is a regular contributor to their quarterly review, Sel de la Terre (Salt of the Earth). The English translations contained in the various tables were prepared with the assistance of H.E. Bishop Richard Williamson, Dr. Andrew Senior (professor at St. Mary’s College, St. Mary’s, Kansas), and Fr. Scott Gardner, SSPX. ollowing the Council, in 1968 a new rite for Orders or is merely “a sacramental,” an ecclesiastical the ordination of bishops was promulgated. ceremony wherein the powers of the episcopate, It was, in fact, the first sacrament to undergo its “bound” in the simple priest, are “freed” for the “aggiornamento,” or updating. -

The Word of God – CSFN Spiritual Formation Notebook #1

Spiritual Formation Notebooks CSFN No. 1 The Word of God in the Life and Writings of Blessed Mary of Jesus the Good Shepherd Frances Siedliska S. Noela Wojtatowicz CSFN The Word of God in the Life and Writings of Blessed Mary of Jesus the Good Shepherd Frances Siedliska S. Noela Wojtatowicz CSFN Rome 2014 2 Author: Sr. Noela Wojtatowicz CSFN Original title: O Słowie Bożym w życiu i pismach bł. Marii od Pana Jezusa Dobrego Pasterza English title: The Word of God in the Life and Writings of Blessed Mary of Jesus the Good Shepherd Frances Siedliska Translator: Stanisław Kacsprzak Cover: Nikodem Rybak 3 CONTENTS FOREWORD………………………………………………………………………………… 5 INTRODUCTION TO THE SUBJECT OF SPIRITUALITY………………………….... 6 1. The Word of God Manifesting Himself in the Bible as a Reality and as a Person……….…9 2. Holy Scripture and the Development of Biblical Studies in Blessed Frances Siedliska’s Times…………………………………………………………………………………….……10 3. Particular Encounters with the Word of God during the Course of Blessed Frances Siedliska’s Life………………………………………………………………….………..…..15 4. Experience of the Word of God in the Life of Blessed Frances Siedliska – the So-Called Mystagogical Function………………………………………………………………………. 17 5. The Word of God as the Most Important Criterion in Reading and Interpreting Events in Blessed Frances Siedliska’s Life…………………………………………...............................19 6. The Word of God as a Priority Reference and “Means” in Describing and Explaining Blessed Frances Siedliska’s Spiritual Experiences…………………………………………...24 A FINAL WORD……………………………………………………………………………62 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………….……………...65 BIBLE QUOTATION STATISTICS IN THE WRITINGS OF BLESSED FRANCES SIEDLISKA…………………………………………………….……………………………66 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………...……….……...67 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE……………………………………………….…………………..72 4 FOREWORD Dear Sisters, We joyfully present Notebook One from the series Notebooks on the Spiritual Formation of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth which treat of the spirituality of Blessed Mary of Jesus the Good Shepherd. -

Tilburg University Herinnering En Belofte. Vijftig Jaar Vaticanum II

Tilburg University Herinnering en belofte. Vijftig jaar Vaticanum II Schelkens, K. Publication date: 2013 Document Version Version created as part of publication process; publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Schelkens, K. (editor) (2013). Herinnering en belofte. Vijftig jaar Vaticanum II. Acco. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. sep. 2021 HERINNERING EN BELOFTE: 50 JAAR VATICANUM II NIKÈ-REEKS Theologische, liturgische en pastorale publicaties Faculteit Theologie en Religiewetenschappen en Liturgisch Instituut, KatholieKe Universiteit Leuven Redactiecomité: Prof. D. Pollefeyt (voorzitter), L. Boeve, J. De Tavernier, J. Geldhof, L. Kenis, G. Van Belle en J. Verstraeten NR. ??? Karim Schelkens (red.) Herinnering en belofte: 50 jaar Vaticanum II Acco Leuven / Voorburg INHOUD Inleiding 7 Ooggetuige Jan Grootaers aan het woord over Vaticanum II Interview door Emmanuel Van Lierde 13 Een rijKe erfenis. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

„Principele Scortesco”. Cine Era? (Cu O Incursiune În Peisajul Catolic Tradiţionalist Din Apus)

1 Un român exilat misterios: „Principele Scortesco”. Cine era? (cu o incursiune în peisajul catolic tradiţionalist din Apus) P. dr. Remus Mircea Birtz, OBSS Summary This study presents some data about the Romanian Traditional Catholic writers, the painter Paul Scorţescu / Scortesco / Scortzesco (1893, Yassy – 1976, Paris), his brother the diplomatic minister Theodor Scorţescu / Scortzesco (1895, Yassy – 1979, Buenos-Aires), known in the Romanian literature, and Miss Myra Davidoglou (1923, Bucharest – 2001, France) a graphic artist too. Some historical and genealogical data about the Scortzesco Moldavian-Romanian noble family are given, and a short landscape of the Traditional Catholic Resistance. It is proven that the well-known statement of Paul Scortzesco about the 1963 Conclave cannot be true, however without denying the election of Cardinal Giuseppe Siri as Pope (Gregory XVII) in the 1958 Conclave. Some biographical data about the Scortzescos can and must be certainly corrected, when new informations from the yet unknown Romanian Exile Culture will be available. Key words: Paul Scorţescu / Scortesco / Scortzesco (1893-1976), Theodor Scorţescu / Scortzesco (1895-1979), Myra Davidoglou (1923-2001), Cardinal Giuseppe Siri (Gregory XVII), Roman Catholic Resistance, Sedevacantism, Romanian Exile. N.B. Studiul a fost prezentat la Simpozionul De la elitele Securităţii la securitatea elitelor organizat de Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai, în 31.III. – 1.IV. 2017, distinsă cu Premiul I, fiind aşteptată publicarea lui în volumul omonim, aflat sub tipar. Dacă Rezistenţa Catolică din România împotriva comunismuluia fost şi este deja amplu investigată şi descrisă, Rezistenţa Catolică din Apusul Europei este practice necunoscută cititorilor români, desi membri marcanţi ai Acesteia au fost şi credincioşi catolici români exilaţi. -

Like Sheep Without a Shepherd”: Sixty Years of Sede Vacante

“Like Sheep without a Shepherd”: Sixty Years of Sede Vacante by Mario Derksen presented on October 11, 2018 When Pope Pius XII died on October 9, 1958, no one could have fathomed the calamities that would befall the Church in the years to come. What we have witnessed in the past six decades is unprecedented, and surely if anyone at the time had been told that in just a few short years, the world would see an apparent Catholic Church that has made peace with the errors of the modern world and transformed the Holy Mass into a Protestant worship service, he would not have believed it. If such a one had been told that the so-called Catholic Church of the next few decades would indoctrinate children and adults in Naturalism and the so-called “rights of man” and engage in efforts to seek the truth conjointly with heretics, Jews, Muslims, and heathens, he would have considered such a prediction insane. So stark is the contrast between the Catholic Church the world knew until the passing of Pope Pius XII and the institution that has since claimed that name, that in 1968, only ten years after Pius XII’s death, the Australian writer Frank Sheed published a book with the telling title, Is it the same Church?.1 The Novus Ordo cardinal Karol Wojtyla, who would later call himself “Pope John Paul II,” wrote in his 1977 book Sign of Contradiction that “the Church succeeded, during the second Vatican Council, in re-defining her own nature.”2 This was apparently also the position of the Vatican, whose Substitute Secretary of State, the Novus Ordo cardinal Giovanni Benelli, in 1976 had been the first to use the term “Conciliar Church” to refer to the new religion that the council had brought about. -

Sunday July 21 , 2019

to live a sacramental life to share our faith SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM 2:00 pm on first and third Sundays. Pre-Baptism class is at 2:00 pm on second Sunday. All by appointment. Sponsors need letter from their pastor. SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION 2:30 - 3:30 pm on Saturday. Anytime upon request. (call for appointment.) SACRAMENT OF MARRIAGE No date should be set prior to seeing a priest or deacon six months before desired date. TO SERVE IN LOVE SACRAMENT OF THE SICK Please contact the Parish office at 614.885.7814. HOLY MASS SCHEDULE SEE BULLETIN FOR HOLY DAYS SATURDAYSATURDAY 8:158:15 am, am,4:00 4:00pm pm SUNDAY 8:30 am, 10:30 am, 12:30 pm SUNDAY 8:30 am, 10:30 am, 12:30 pm DAILY 6:30 am MON.-FRI. DAILY 8:156:30 am amMON., MON WED., - FRI THURS., FRI., SAT. 7:008:15 pm amTUE. MON, WED, THURS, FRI, SAT 7:00 pm TUE 614.885.7814 SAINTMICHAEL-CD.ORG facebook.com/stmichaelworthington 5750 NORTH HIGH STREET WORTHINGTON, OHIO 43085 PDF DOCUMENT ONCE DTP! SAINT MICHAEL JULY 21, 2019 PARISH STAFF 16TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME PARISH CONTACT DAILY MASS INTENTIONS AND READINGS INFORMATION SUNDAY, JULY 21 TELEPHONES 8:30 a.m. Special Intention of The Miller Family Parish Office: 885-7814 10:30 a.m. For the People St. Michael Fax: 885-8060 12:30 p.m. Barbara Montgomery Moore (Michael & Nora Kazor) School Office: 885-3149 Rel. Ed.: 888-5384 Monday, July 22 Cafeteria: 885-8268 6:30 a.m.