2019-012704Crv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFO to San Francisco in 45 Minutes for Only $6.55!* in 30 Minutes for Only $5.35!*

Fold in to the middle; outside right Back Panel Front Panel Fold in to the middle; outside left OAK to San Francisco SFO to San Francisco in 45 minutes for only $6.55!* in 30 minutes for only $5.35!* BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) from OAK is fast, easy and BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) provides one of the world’s inexpensive too! Just take the convenient AirBART shuttle Visitors Guide best airport-to-downtown train services. BART takes you bus from OAK to BART to catch the train to downtown San downtown in 30 minutes for only $5.35 one-way or $10.70 Francisco. The entire trip takes about 45 minutes and costs round trip. It’s the fast, easy, inexpensive way to get to only $6.55 one-way or $13.10 round trip. to BART San Francisco. The AirBART shuttle departs every 15 minutes from the The BART station is located in the SFO International Terminal. 3rd curb across from the terminals. When you get off the It’s only a five minute walk from Terminal Three and a shuttle at the Coliseum BART station, buy a round trip BART 10 minute walk from Terminal One. Both terminals have ticket from the ticket machine. Take the escalator up to the Powell Street-Plaza Entrance connecting walkways to the International Terminal. You can westbound platform and board a San Francisco or Daly City also take the free SFO Airtrain to the BART station. bound train. The BART trip to San Francisco takes about 20 minutes. Terminal 2 (under renovation) Gates 40 - 48 Gates 60 - 67 Terminal 3 Terminal 1 Gates 68 - 90 Gates 20 - 36 P Domestic Want to learn about great deals on concerts, plays, Parking museums and other activities during your visit? Go to www.mybart.org to learn about fantastic special offers for BART customers. -

PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION March 28, 2017 Agenda ID# 15631

STATE OF CALIFORNIA EDMUND G. BROWN JR., Governor PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION 505 VAN NESS AVENUE SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94102 March 28, 2017 Agenda ID# 15631 TO PARTIES TO RESOLUTION ST-203 This is the Resolution of the Safety and Enforcement Division. It will be on the April 27, 2017, Commission Meeting agenda. The Commission may act then, or it may postpone action until later. When the Commission acts on the Resolution, it may adopt all or part of it as written, amend or modify it, or set it aside and prepare its own decision. Only when the Commission acts does the resolution become binding on the parties. Parties may file comments on the Resolution as provided in Article 14 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure (Rules), accessible on the Commission’s website at www.cpuc.ca.gov. Pursuant to Rule 14.3, opening comments shall not exceed 15 pages. Late-submitted comments or reply comments will not be considered. An electronic copy of the comments should be submitted to Colleen Sullivan (email: [email protected]). /s/ ELIZAVETA I. MALASHENKO ELIZAVETA I. MALASHENKO, Director Safety and Enforcement Division SUL:vdl Attachment CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I certify that I have by mail this day served a true copy of Draft Resolution ST-203 on all identified parties in this matter as shown on the attached Service List. Dated March 28, 2017, at San Francisco, California. /s/ VIRGINIA D. LAYA Virginia D. Laya NOTICE Parties should notify the Safety Enforcement Division, California Public Utilities Commission, 505 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94102, of any change of address to ensure that they continue to receive documents. -

ACT BART S Ites by Region.Csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7

Services Transit Outreach Materials Distribution Light Rail Station Maintenance and Inspection Photography—Capture Metadata and GPS Marketing Follow-Up Programs Service Locations Dallas, Los Angeles, Minneapolis/Saint Paul San Francisco/Oakland Bay Area Our Customer Service Pledge Our pledge is to organize and act with precision to provide you with excellent customer service. We will do all this with all the joy that comes with the morning sun! “I slept and dreamed that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy. “Tagore Email: [email protected] Website: URBANMARKETINGCHANNELS.COM Urban Marketing Channel’s services to businesses and organizations in Atlanta, Dallas, San Francisco, Oakland and the Twin Cities metro areas since 1981 have allowed us to develop a specialty client base providing marketing outreach with a focus on transit systems. Some examples of our services include: • Neighborhood demographic analysis • Tailored response and mailing lists • Community event monitoring • Transit site management of information display cases and kiosks • Transit center rider alerts • Community notification of construction and route changes • On-Site Surveys • Enhance photo and list data with geocoding • Photographic services Visit our website (www.urbanmarketingchannels.com) Contact us at [email protected] 612-239-5391 Bay Area Transit Sites (includes BART and AC Transit.) Prepared by Urban Marketing Channels ACT BART S ites by Region.csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7 UnSANtit -

AQ Conformity Amended PBA 2040 Supplemental Report Mar.2018

TRANSPORTATION-AIR QUALITY CONFORMITY ANALYSIS FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT Metropolitan Transportation Commission Association of Bay Area Governments MARCH 2018 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Jake Mackenzie, Chair Dorene M. Giacopini Julie Pierce Sonoma County and Cities U.S. Department of Transportation Association of Bay Area Governments Scott Haggerty, Vice Chair Federal D. Glover Alameda County Contra Costa County Bijan Sartipi California State Alicia C. Aguirre Anne W. Halsted Transportation Agency Cities of San Mateo County San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission Libby Schaaf Tom Azumbrado Oakland Mayor’s Appointee U.S. Department of Housing Nick Josefowitz and Urban Development San Francisco Mayor’s Appointee Warren Slocum San Mateo County Jeannie Bruins Jane Kim Cities of Santa Clara County City and County of San Francisco James P. Spering Solano County and Cities Damon Connolly Sam Liccardo Marin County and Cities San Jose Mayor’s Appointee Amy R. Worth Cities of Contra Costa County Dave Cortese Alfredo Pedroza Santa Clara County Napa County and Cities Carol Dutra-Vernaci Cities of Alameda County Association of Bay Area Governments Supervisor David Rabbit Supervisor David Cortese Councilmember Pradeep Gupta ABAG President Santa Clara City of South San Francisco / County of Sonoma San Mateo Supervisor Erin Hannigan Mayor Greg Scharff Solano Mayor Liz Gibbons ABAG Vice President City of Campbell / Santa Clara City of Palo Alto Representatives From Mayor Len Augustine Cities in Each County City of Vacaville -

Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report

Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report May 7, 2015 Prepared jointly by CDM Smith and the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District, Office of Civil Rights 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Section 1: Introduction 6 Section 2: Project Description 7 Section 3: Methodology 14 Section 4: Service Analysis Findings 23 Section 5: Fare Analysis Findings 27 Appendix A: 2011 Warm Springs Survey 33 Appendix B: Proposed Service Options Description 36 Public Participation Report 4 1 2 Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report Executive Summary In June 2011, staff completed a Title VI Analysis for the Warm Springs Extension Project (Project). Per the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Title VI Circular (Circular) 4702.1B, Title VI Requirements and Guidelines for Federal Transit Administration Recipients (October 1, 2012), the District is required to conduct a Title VI Service and Fare Equity Analysis (Title VI Equity Analysis) for the Project's proposed service and fare plan six months prior to revenue service. Accordingly, staff completed an updated Title VI Equity Analysis for the Project’s service and fare plan, which evaluates whether the Project’s proposed service and fare will have a disparate impact on minority populations or a disproportionate burden on low-income populations based on the District’s Disparate Impact and Disproportionate Burden Policy (DI/DB Policy) adopted by the Board on July 11, 2013 and FTA approved Title VI service and fare methodologies. Discussion: The Warm Springs Extension will add 5.4-miles of new track from the existing Fremont Station south to a new station in the Warm Springs district of the City of Fremont, extending BART’s service in southern Alameda County. -

2015 Station Profiles

2015 BART Station Profile Study Station Profiles – Non-Home Origins STATION PROFILES – NON-HOME ORIGINS This section contains a summary sheet for selected BART stations, based on data from customers who travel to the station from non-home origins, like work, school, etc. The selected stations listed below have a sample size of at least 200 non-home origin trips: • 12th St. / Oakland City Center • Glen Park • 16th St. Mission • Hayward • 19th St. / Oakland • Lake Merritt • 24th St. Mission • MacArthur • Ashby • Millbrae • Balboa Park • Montgomery St. • Civic Center / UN Plaza • North Berkeley • Coliseum • Oakland International Airport (OAK) • Concord • Powell St. • Daly City • Rockridge • Downtown Berkeley • San Bruno • Dublin / Pleasanton • San Francisco International Airport (SFO) • Embarcadero • San Leandro • Fremont • Walnut Creek • Fruitvale • West Dublin / Pleasanton Maps for these stations are contained in separate PDF files at www.bart.gov/stationprofile. The maps depict non-home origin points of customers who use each station, and the points are color coded by mode of access. The points are weighted to reflect average weekday ridership at the station. For example, an origin point with a weight of seven will appear on the map as seven points, scattered around the actual point of origin. Note that the number of trips may appear underrepresented in cases where multiple trips originate at the same location. The following summary sheets contain basic information about each station’s weekday non-home origin trips, such as: • absolute number of entries and estimated non-home origin entries • access mode share • trip origin types • customer demographics. Additionally, the total number of car and bicycle parking spaces at each station are included for context. -

Chapter 3: Environmental Setting and Consequences

CHAPTER 3: ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING AND CONSEQUENCES CHAPTER 3: ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING AND CONSEQUENCES This chapter presents information on the environmental setting in the project area as well as the environmental consequences of the No-Electrification and Electrification Program Alternatives. Environmental issue categories are organized in alphabetical order, consistent with the CEQA checklist presented in Appendix A. The project study area encompasses the geographic area potentially most affected by the project. For most issues involving physical effects this is the project “footprint,” or the area that would be disturbed for or replaced by the new project facilities. This area focuses on the Caltrain corridor from the San Francisco Fourth and King Station in the City and County of San Francisco to the Gilroy Station in downtown Gilroy in Santa Clara County and also includes the various locations proposed for traction power facilities and power connections. Air quality effects may be felt over a wider area. 3.1 AESTHETICS 3.1.1 VISUAL OR AESTHETIC SETTING The visual or aesthetic environment in the Caltrain corridor is described to establish the baseline against which to compare changes resulting from construction of project facilities and the demolition or alteration of existing structures. This discussion focuses on representative locations along the railroad corridor, including existing stations (both modern and historic), tunnel portals, railroad overpasses, locations of the proposed traction power facilities and other areas where the Electrification Program would physically change above-ground features, affecting the visual appearance of the area and views enjoyed by area residents and users. For purposes of this analysis, sensitive visual receptors are defined as corridor residents and business occupants, recreational users of parks and preserved natural areas, and students of schools in the vicinity of the proposed project. -

PRIMARY RECORD NRHP Status Code:7 Other Listings: Review Code: � Reviewer: Survey #: Date: 44- DOE

State of California - The Resource Agency Primary #:____________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI#:_________________________________ Trinomial: PRIMARY RECORD NRHP Status Code:7 Other Listings: Review Code: Reviewer: Survey #: Date: 44- DOE #: *Resource Name or #:5 Chilton Av P1. Other Identifier: *P2 Location: not for publication Z unrestricted *a . County San Francisco and (P2c, P2e, and P21b or P2d. Attach a Location Map as Necessary) b. USGS 7.5' Quad: YEAR: T ;R ; of of Sec B.M. c. Address: 5 Chilton AV City: San Francisco State: CA Zip Code: 94131 d. UTM: (Give more than one for large and/or linear resources) Zone: ; mE/ mN e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc., as appropriate) 6738 031 & 032 (formerly lot 25) *133a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) See Continuation Sheet *P3b Resource Attributes: (List attributes and codes) HP02 5 P4 Resources Present: Z Building D Structure 0 Object 0 Site 0 District 0 Element of a District 0 Other 135b. Description of Photo: *P6. Date Constructed/Age and Source: U Historic 0 PreHistoric 0 Both 0 Neither Year Built: 1908 - Documented p7 Owner and Address: Name: KINNEAR LESLEY / EAKIN-SZENTMIKLOSSY FMLY TR Address: 5 CHILTON AVE San Francisco,CA 94131 *P8 Recorded By: N. Moses Corrette City Planner San Francisco Planning Department 1650 Mission Street, Suite 400 San Francisco, CA 94103 *9 Date Recorded: 08/10/2009 -

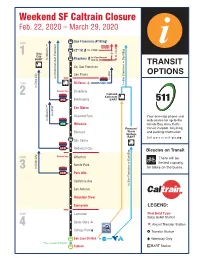

Weekend SF Caltrain Closure Feb

Weekend SF Caltrain Closure Feb. 22, 2020 – March 29, 2020 San Francisco (4th/King) ZONE st nd to 3rd/20th 22 St 8 1 Daly T 9 City to San Bruno/ BART to Mission/1 Bayshore Arleta So. San Francisco TRANSIT San Bruno OPTIONS to Downtown San Francisco to SFO SFO ZONE Millbrae to San Francisco or East Bay to Daly City Weekend Only Broadway 2 Oakland Coliseum 292 Burlingame BART st San Mateo via SFO Hayward Park Your one-stop phone and to Mission/1 web source for up-to-the 398 Hillsdale minute Bay Area traffic, Fremont/ transit, carpool, bicycling Belmont Warm and parking information Springs BART San Carlos ECR Redwood City Bicycles on Transit Weekend Only ZONE Atherton There will be limited capacity Menlo Park 3 to Daly City for bikes on the buses. ECR Palo Alto California Ave to San Francisco or East Bay San Antonio Mountain View Sunnyvale LEGEND: ZONE Lawrence Red Bold Type - Baby Bullet Station Santa Clara 4 Airport Transfer Station College Park ◊ • Transfer Station San Jose Diridon 181 ◊ Weekday Only Free weekend Shuttle Tamien BART Station Caltrain will NOT provide weekend service to San Francisco or 22nd Street stations February 22, 2020 to March 29, 2020. Trains will terminate at Bayshore Station. Free bus service will be available for Caltrain riders from Bayshore Station to 22nd Street and San Francisco stations. Listed below are some transit options that might work better for you. Connect with BART (bart.gov) at the Use SamTrans Bus Service (Limited Millbrae Transit Center Number of Bikes Allowed) Estimated Travel Time (From Millbrae BART From/To Downtown San Francisco Station): Route 292 (samtrans.com/292) • Approx. -

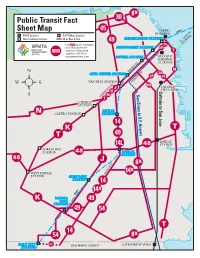

Transit Fact Sheet and Muni Tips With

8x Public Transit Fact 30 Sheet Map 45 FERRY BUILDING BART BART Stations BART/Muni Stations AND AKL GE ID Muni Subway Stations Muni Bus & Rail EMBARCADERO STATION - O F. 49 S. Y BR For route, schedule, 14 BA fare and accessible MONTGOMERY STATION 14x services information T anytime: Call 311 or visit www.sfmta.com POWELL STATION TRANSBAY TERMINAL (AC TRANSIT) N MARKET ST. CIVIC CENTER STATION 30 8x 45 VAN NESS STATION MISSION ST. D x N 14 U CALTRAIN O J R Caltrain to San Jose San to Caltrain 4TH & KING G K ER D SamTrans to S.F. Airport N N U T CHURCH STATION 16TH ST. N CASTRO STATION STATION 14 K T T 49 22ND ST. 14L 48 STATION FOREST HILL STATION 48 24TH ST. STATION 48 J 8x 14x WEST PORTAL MISSION ST. STATION GLEN PARK STATION 14 14x BART BALBOA K PARK 49 STATION 49 54 T 14 54 8x DALY CITY 14L SAN MATEO COUNTY BAYSHORE STATION STATION San Francisco Public Transit Options FACT SHEET AND MUNI ROUTE TIPS Muni bus routes providing alternate, parallel service to BART service within San Francisco are indicated with numbers, while Muni rail lines are indicated with letters. Adult full Muni fare is $2. Youth and Senior/Disabled fare is 75 cents. Exact change or Clipper Cards are required on Muni vehicles; Muni Metro tickets can be purchased at the Metro vend- ing machines in the subway stations for use at subway fare gates. To reach San Francisco International Airport or other peninsula destinations use SamTrans or Caltrain service. -

Item # Agenda ID # 16651 (Rev. 2) PROPOSED RESOLUTION Safety

SED/RTSB/EIM/RNC/DAR/JEB/PD2 Item # Agenda ID # 16651 (Rev. 2) PROPOSED RESOLUTION PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Safety and Enforcement Division Resolution ST‐216 Rail Transit Safety Branch September 27, 2018 REDACTED RESOLUTION RESOLUTION ST‐216 GRANTING APPROVAL OF THE FINAL REPORT ON THE 2017 TRIENNIAL ON‐SITE SECURITY REVIEW OF BAY AREA RAPID TRANSIT DISCTRICT SUMMARY This resolution approves the California Public Utilities Commission Safety and Enforcement Division final report titled, ʺ2017 Triennial On‐Site Security Review of Bay Area Rapid Transit District,ʺ dated November 12, 2017. The report compiles the results of Commission Staff review of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District’s security program. Only background information and review procedures are included in the redacted report; findings and recommendations are not. BACKGROUND Commission General Order No. 164‐D, ʺRules and Regulations Governing State Safety Oversight of Rail Fixed Guideway Systemsʺ requires Commission Staff (Staff) to conduct on‐site security review of the transit agencies operating rail fixed guideway systems triennially. From 1996 to 2008, the Commission’s Rail Transit Safety staff partnered with the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in performing rail transit security reviews. However, in the latter half of 2008, Commission 228548656 - 1 - SED/RTSB/EIM/RNC/DAR/JEB/PD2 Resolution ST‐216 Agenda ID # 16651 September 27, 2018 PROPOSED RESOLUTION Staff took over the responsibility of security reviews from the TSA. Staff conducted an on‐site security review of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) security program in October 2017. BART provides rail transit services 365 days of the year throughout the counties of San Francisco, Alameda, San Mateo, and Contra Costa. -

Grace Morley, the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Early En- Vironmental Agenda of the Bay Region (193X-194X)»

Recibido: 15/7/2018 Aceptado: 22/11/2018 Para enlazar con este artículo / To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.14198/fem.2018.32.04 Para citar este artículo / To cite this article: Parra-Martínez, José & Crosse, John. «Grace Morley, the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Early En- vironmental Agenda of the Bay Region (193X-194X)». En Feminismo/s, 32 (diciembre 2018): 101-134. Dosier monográfico: MAS-MES: Mujeres, Arquitectura y Sostenibilidad - Medioambiental, Económica y Social, coord. María-Elia Gutiérrez-Mozo, DOI: 10.14198/fem.2018.32.04 GRACE MORLEY, THE SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF ART AND THE EARLY ENVIRONMENTAL AGENDA OF THE BAY REGION (193X-194X) GRACE MCCANN MORLEY Y EL MUSEO DE ARTE DE SAN FRANCISCO EN LOS INICIOS DE LA AGENDA MEDIOAMBIENTAL DE LA REGIÓN DE LA BAHÍA (193X-194X) primera José PARRA-MARTÍNEZ Universidad de Alicante [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0003-0142-0608 John CROSSE Retired Assistant Director, City of Los Angeles, Bureau of Sanitation, California [email protected] Abstract This paper addresses the instrumental role played by Dr Grace L. McCann Morley, the founding director of the San Francisco Museum of Art (1935-58), in establishing a pioneering architectural exhibition program which, as part of a coherent public agenda, not only had a tremendous impact on the education and enlightenment of her community, but also reached some of the most influential actors in the United States who, like cultural critic Lewis Mumford, were exposed and seduced by the so-called Second Bay Region School and its emphasis on social, political and environ- mental concerns.