Glen Park Community Plan San Francisco, California PBS&J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACT BART S Ites by Region.Csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7

Services Transit Outreach Materials Distribution Light Rail Station Maintenance and Inspection Photography—Capture Metadata and GPS Marketing Follow-Up Programs Service Locations Dallas, Los Angeles, Minneapolis/Saint Paul San Francisco/Oakland Bay Area Our Customer Service Pledge Our pledge is to organize and act with precision to provide you with excellent customer service. We will do all this with all the joy that comes with the morning sun! “I slept and dreamed that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy. “Tagore Email: [email protected] Website: URBANMARKETINGCHANNELS.COM Urban Marketing Channel’s services to businesses and organizations in Atlanta, Dallas, San Francisco, Oakland and the Twin Cities metro areas since 1981 have allowed us to develop a specialty client base providing marketing outreach with a focus on transit systems. Some examples of our services include: • Neighborhood demographic analysis • Tailored response and mailing lists • Community event monitoring • Transit site management of information display cases and kiosks • Transit center rider alerts • Community notification of construction and route changes • On-Site Surveys • Enhance photo and list data with geocoding • Photographic services Visit our website (www.urbanmarketingchannels.com) Contact us at [email protected] 612-239-5391 Bay Area Transit Sites (includes BART and AC Transit.) Prepared by Urban Marketing Channels ACT BART S ites by Region.csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7 UnSANtit -

2012 San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Status Report Presented to the CITIZENS’ GENERAL OBLIGATION BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE

2012 San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Status Report Presented to the CITIZENS’ GENERAL OBLIGATION BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE May 2018 McLaren Bike Park Opening Prepared by: Antonio Guerra, Capital Finance Manager, Recreation and Parks 415‐581‐2554, [email protected] Ananda Hirsch, Capital Manager, Port of San Francisco 415‐274‐0442, [email protected] 2012 San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Status Report Presented to the CITIZENS’ GENERAL OBLIGATION BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE May 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Program Budget Project Revenues 2 Project Expenditures 4 Project Schedules 6 Project Status Summaries 8 Citywide Programs 2930 Citywide Parks 3334 Executive Summary San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Bond Program Budget $M Neighborhood Parks In November 2012, 71.6% of voters approved Proposition B for a Angelo J. Rossi Playground 8.2 $195 million General Obligation Bond, known as the 2012 San Balboa Park 7 Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond (the “bond”). Garfield Square 11 George Chri s topher Playground 2.8 This funding will continue a decade of investment in the aging Gilman Playground 1.8 infrastructure of our park system. Specifically, the bond Glen Ca nyon Park 12 allocates: Hyde & Turk Mini Park 1 Joe DiMaggio Playground 5.5 Margaret S. Hayward Playground 14 $99 million for Neighborhood Parks, selected based on Moscone Recreation Center 1.5 community feedback, their physical condition, the variety of Mountain Lake Park 2 amenities offered, -

Glen Park News Spring 2014

SPRING 2014 VOLUME 32, NO. 1 Muni Reworks 35-Eureka Line New Playground Comes Alive Reroute Plan he San Francisco Municipal Transportaion Agency appears T ready to back off its controver- sial rerouting plan to run the 35-Eureka by bus along Diamond Zachary Street and eliminate Clark direct bus service to another portion of Glen Park altogether, after neighbors rallied to stop the proposed change. Muni’s original proposal, unveiled last winter, called for eliminating the 35-Eureka’s current loop along Moffitt, Bemis and Addison streets and extend the route south along Diamond Street to serve the Glen Park BART station. The 35-Eureka proposal is part of the San Francisco Municipal Transpor- tation Agency’s Transit Effectiveness Project, which aims make the public transit system more efficient, reliable, safe and comfortable for its riders, in part by overhauling routes. The goal behind the 35-Eureka Glen Park children and parents enjoy the playground during opening week. Photo by Liz Mangelsdorf change is to provide a direct Muni link between the Castro and Noe Val- ids being kids, they would not draw was the canyon. Now, it feels like ley neighborhoods and the Glen Park wait for the official inaugura- the playground is a destination, too.” BART station. K tion of the renovated Glen Can- The $5.8 million Glen Canyon Park While many residents are in favor yon Park Playground. They poured in playground improvements were funded of connecting the bus to BART, there before the speeches were over, before by the voter-backed 2008 Clean and was fierce opposition to the Diamond by the ribbon was cut. -

File No. 131042 Amended in Board 11/5/13 Resolution No

AMENDED IN BOARD 11/5/13 FILE NO. 131042 RESOLUTION NO. 391-13 1 [Park, Recreation, and Open Space Advisory Committee - Membership List] 2 3 Resolution approving and modifying the Recreation and Park Commission's list of 4 recommended organizations for membership in the Park, Recreation, and Open Space 5 Advisory Committee. 6 7 WHEREAS, San Francisco Park Code, Article 13, Section 13.01, established the Park, 8 Recreation and Open Space Advisory Committee. That Ordinance provides that the 9 Recreation and Park Commission shall prepare, and the Board of Supervisors shall approve 1O or modify, a list of organizations qualified to nominate individuals for Park, Recreation and 11 Open Space Advisory Committee membership; now, therefore, be it 12 RESOLVED, That the list of recommended organizations qualified to nominate 13 individuals for Park Recreation and Open Space Advisory Committee membership are: 14 California Native Plant Society- Verba Buena Chapter, Friends of Duboce Park, Friends of 15 Mountain Lake Park, Friends of Recreation and Parks, Golden Gate Audubon Society - San 16 Francisco Conservation Committee, People Organizing to Demand Environmental Rights, 17 Proposition E Implementation Committee, San Francisco Beautiful, Neighborhood Park 18 Council, Committee for Better Parks and Recreation in Chinatown, San Francisco Friends of 19 the Urban Forest, San Francisco Group of the Sierra Club, San Francisco League of 20 Conservation Voters, San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners, San Francisco Tomorrow, 21 Save the Redwoods League, -

Monthly Capital Report October 2018

San Francisco Recreation and Parks Capital & Planning Division Monthly Report September 30, 2018 Toks Ajike Director of Planning and Capital Management Prepared by: Antonio Guerra, Capital Finance Manager The City and County of San Francisco launched the PeopleSoft financial and procurement system on July 3, 2017. This new financial system replaces the over 20-year old FAMIS system and completely changes the way the department processes and reports on financial transactions and procurement. As such, there have been some changes in the standard monthly capital report. This report contains the following: Active project balances and non-reconciled closed projects Unlike previous monthly reports, this report does not show FY 2018-19 actuals due to changes in the People Soft BI reporting syastem. The Department hopes to have this data in time for the November 2018 monthly report. Recreation and Parks Monthly Capital Report ‐ September 30, 2018 Project Description Budget Actuals Encumbered Balance PW Mansell St Strtscp 1,718,517.08 1,668,345.86 3,777.25 46,393.97 PW TGHill Rockslide Rsp 3,111.05 2,526.45 0.00 584.60 RP 11th & Natoma Acquistion 9,866,104.26 9,830,256.41 0.00 35,847.85 RP 11th Street And Natoma Park 210,000.00 9.30 9,620.00 200,370.70 RP 1268p‐marina Harbor Bioswal 780,177.00 56,377.81 0.00 723,799.19 RP 1290P‐Shoreview Park 3,932.00 53,183.82 0.00 ‐49,251.82 RP 1291P‐Ggp Senior Center 48,538.16 27,875.12 13,051.20 7,611.84 RP 17th & Folsom Park Acq 3,190.00 0.00 0.00 3,190.00 RP 17Th And Folsom 4,976,560.11 4,921,987.49 88,978.69 -

Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan Environmental Assessment

1. Introduction The Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan and Environmental Assessment is a cooperative effort between the Presidio Trust (Trust), the National Park Service (NPS), and the Golden Gate National Parks Association (GGNPA). The Presidio Trust is a wholly- owned federal government corporation whose purposes are to preserve and enhance the Presidio as a national park, while at the same time ensuring that the Presidio becomes financially self-sufficient by 2013. The Trust assumed administrative jurisdiction over 80 percent of the Presidio on July 1, 1998, and the NPS retains jurisdiction over the coastal areas. The Trust is managed by a seven-person Board of Directors, on which a Department of Interior representative serves. NPS, in cooperation with the Trust, provides visitor services and interpretive and educational programs throughout the Presidio. The Trust is lead agency for environmental review and compliance under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). GGNPA is administering project funds and coordinating phase one of the project. The San Francisco International Airport has provided $500,000 to fund the first phase of the Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan under the terms and conditions outlined within the Cooperative Agreement for the Restoration of Mountain Lake, 24 July 1998. The overall goal of the Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan is to improve the health of the lake and adjacent shoreline and terrestrial environments within the 14.25-acre Project Area. This document analyzes three site plan alternatives (Alternatives 1, 2, and 3) and a no action alternative. It is a project-level EA that is based upon the Presidio Trust Act and the 1994 General Management Plan Amendment for the Presidio of San Francisco (GMPA) prepared by the NPS, a planning document that provides guidelines regarding the management, use, and development of the Presidio. -

Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report

Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report May 7, 2015 Prepared jointly by CDM Smith and the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District, Office of Civil Rights 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Section 1: Introduction 6 Section 2: Project Description 7 Section 3: Methodology 14 Section 4: Service Analysis Findings 23 Section 5: Fare Analysis Findings 27 Appendix A: 2011 Warm Springs Survey 33 Appendix B: Proposed Service Options Description 36 Public Participation Report 4 1 2 Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report Executive Summary In June 2011, staff completed a Title VI Analysis for the Warm Springs Extension Project (Project). Per the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Title VI Circular (Circular) 4702.1B, Title VI Requirements and Guidelines for Federal Transit Administration Recipients (October 1, 2012), the District is required to conduct a Title VI Service and Fare Equity Analysis (Title VI Equity Analysis) for the Project's proposed service and fare plan six months prior to revenue service. Accordingly, staff completed an updated Title VI Equity Analysis for the Project’s service and fare plan, which evaluates whether the Project’s proposed service and fare will have a disparate impact on minority populations or a disproportionate burden on low-income populations based on the District’s Disparate Impact and Disproportionate Burden Policy (DI/DB Policy) adopted by the Board on July 11, 2013 and FTA approved Title VI service and fare methodologies. Discussion: The Warm Springs Extension will add 5.4-miles of new track from the existing Fremont Station south to a new station in the Warm Springs district of the City of Fremont, extending BART’s service in southern Alameda County. -

2015 Station Profiles

2015 BART Station Profile Study Station Profiles – Non-Home Origins STATION PROFILES – NON-HOME ORIGINS This section contains a summary sheet for selected BART stations, based on data from customers who travel to the station from non-home origins, like work, school, etc. The selected stations listed below have a sample size of at least 200 non-home origin trips: • 12th St. / Oakland City Center • Glen Park • 16th St. Mission • Hayward • 19th St. / Oakland • Lake Merritt • 24th St. Mission • MacArthur • Ashby • Millbrae • Balboa Park • Montgomery St. • Civic Center / UN Plaza • North Berkeley • Coliseum • Oakland International Airport (OAK) • Concord • Powell St. • Daly City • Rockridge • Downtown Berkeley • San Bruno • Dublin / Pleasanton • San Francisco International Airport (SFO) • Embarcadero • San Leandro • Fremont • Walnut Creek • Fruitvale • West Dublin / Pleasanton Maps for these stations are contained in separate PDF files at www.bart.gov/stationprofile. The maps depict non-home origin points of customers who use each station, and the points are color coded by mode of access. The points are weighted to reflect average weekday ridership at the station. For example, an origin point with a weight of seven will appear on the map as seven points, scattered around the actual point of origin. Note that the number of trips may appear underrepresented in cases where multiple trips originate at the same location. The following summary sheets contain basic information about each station’s weekday non-home origin trips, such as: • absolute number of entries and estimated non-home origin entries • access mode share • trip origin types • customer demographics. Additionally, the total number of car and bicycle parking spaces at each station are included for context. -

100 Things to Do in San Francisco*

100 Things to Do in San Francisco* Explore Your New Campus & City MORNING 1. Wake up early and watch the sunrise from the top of Bernal Hill. (Bernal Heights) 2. Uncover antique treasures and designer deals at the Treasure Island Flea Market. (Treasure Island) 3. Go trail running in Glen Canyon Park. (Glen Park) 4. Swim in Aquatic Park. (Fisherman's Wharf) 5. Take visitors to Fort Point at the base of the Golden Gate Bridge, where Kim Novak attempted suicide in Hitchcock's Vertigo. (Marina) 6. Get Zen on Sundays with free yoga classes in Dolores Park. (Dolores Park) 7. Bring Your Own Big Wheel on Easter Sunday. (Potrero Hill) 8. Play tennis at the Alice Marble tennis courts. (Russian Hill) 9. Sip a cappuccino on the sidewalk while the cable car cruises by at Nook. (Nob Hill) 10. Take in the views from seldom-visited Ina Coolbrith Park and listen to the sounds of North Beach below. (Nob Hill) 11. Brave the line at the Swan Oyster Depot for fresh seafood. (Nob Hill) *Adapted from 7x7.com 12. Drive down one of the steepest streets in town - either 22nd between Vicksburg and Church (Noe Valley) or Filbert between Leavenworth and Hyde (Russian Hill). 13. Nosh on some goodies at Noe Valley Bakery then shop along 24th Street. (Noe Valley) 14. Play a round of 9 or 18 at the Presidio Golf Course. (Presidio) 15. Hike around Angel Island in spring when the wildflowers are blooming. 16. Dress up in a crazy costume and run or walk Bay to Breakers. -

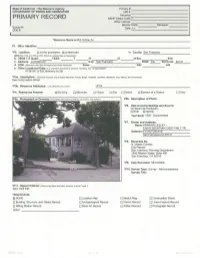

PRIMARY RECORD NRHP Status Code:7 Other Listings: Review Code: � Reviewer: Survey #: Date: 44- DOE

State of California - The Resource Agency Primary #:____________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI#:_________________________________ Trinomial: PRIMARY RECORD NRHP Status Code:7 Other Listings: Review Code: Reviewer: Survey #: Date: 44- DOE #: *Resource Name or #:5 Chilton Av P1. Other Identifier: *P2 Location: not for publication Z unrestricted *a . County San Francisco and (P2c, P2e, and P21b or P2d. Attach a Location Map as Necessary) b. USGS 7.5' Quad: YEAR: T ;R ; of of Sec B.M. c. Address: 5 Chilton AV City: San Francisco State: CA Zip Code: 94131 d. UTM: (Give more than one for large and/or linear resources) Zone: ; mE/ mN e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc., as appropriate) 6738 031 & 032 (formerly lot 25) *133a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) See Continuation Sheet *P3b Resource Attributes: (List attributes and codes) HP02 5 P4 Resources Present: Z Building D Structure 0 Object 0 Site 0 District 0 Element of a District 0 Other 135b. Description of Photo: *P6. Date Constructed/Age and Source: U Historic 0 PreHistoric 0 Both 0 Neither Year Built: 1908 - Documented p7 Owner and Address: Name: KINNEAR LESLEY / EAKIN-SZENTMIKLOSSY FMLY TR Address: 5 CHILTON AVE San Francisco,CA 94131 *P8 Recorded By: N. Moses Corrette City Planner San Francisco Planning Department 1650 Mission Street, Suite 400 San Francisco, CA 94103 *9 Date Recorded: 08/10/2009 -

2012 Park Bond Funds $5 Million in Conservation Measures

2012 San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Status Report Presented to the CITIZENS’ GENERAL OBLIGATION BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE May 2018 McLaren Bike Park Opening Prepared by: Antonio Guerra, Capital Finance Manager, Recreation and Parks 415‐581‐2554, [email protected] Ananda Hirsch, Capital Manager, Port of San Francisco 415‐274‐0442, [email protected] 2012 San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Status Report Presented to the CITIZENS’ GENERAL OBLIGATION BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE May 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Program Budget Project Revenues 2 Project Expenditures 4 Project Schedules 6 Project Status Summaries 8 Citywide Programs 30 Citywide Parks 34 Executive Summary San Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond Bond Program Budget $M Neighborhood Parks In November 2012, 71.6% of voters approved Proposition B for a Angelo J. Rossi Playground 8.2 $195 million General Obligation Bond, known as the 2012 San Balboa Park 7 Francisco Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond (the “bond”). Garfield Square 11 George Chri s topher Playground 2.8 This funding will continue a decade of investment in the aging Gilman Playground 1.8 infrastructure of our park system. Specifically, the bond Glen Ca nyon Park 12 allocates: Hyde & Turk Mini Park 1 Joe DiMaggio Playground 5.5 Margaret S. Hayward Playground 14 $99 million for Neighborhood Parks, selected based on Moscone Recreation Center 1.5 community feedback, their physical condition, the variety of Mountain Lake Park 2 amenities offered, -

Grace Morley, the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Early En- Vironmental Agenda of the Bay Region (193X-194X)»

Recibido: 15/7/2018 Aceptado: 22/11/2018 Para enlazar con este artículo / To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.14198/fem.2018.32.04 Para citar este artículo / To cite this article: Parra-Martínez, José & Crosse, John. «Grace Morley, the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Early En- vironmental Agenda of the Bay Region (193X-194X)». En Feminismo/s, 32 (diciembre 2018): 101-134. Dosier monográfico: MAS-MES: Mujeres, Arquitectura y Sostenibilidad - Medioambiental, Económica y Social, coord. María-Elia Gutiérrez-Mozo, DOI: 10.14198/fem.2018.32.04 GRACE MORLEY, THE SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF ART AND THE EARLY ENVIRONMENTAL AGENDA OF THE BAY REGION (193X-194X) GRACE MCCANN MORLEY Y EL MUSEO DE ARTE DE SAN FRANCISCO EN LOS INICIOS DE LA AGENDA MEDIOAMBIENTAL DE LA REGIÓN DE LA BAHÍA (193X-194X) primera José PARRA-MARTÍNEZ Universidad de Alicante [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0003-0142-0608 John CROSSE Retired Assistant Director, City of Los Angeles, Bureau of Sanitation, California [email protected] Abstract This paper addresses the instrumental role played by Dr Grace L. McCann Morley, the founding director of the San Francisco Museum of Art (1935-58), in establishing a pioneering architectural exhibition program which, as part of a coherent public agenda, not only had a tremendous impact on the education and enlightenment of her community, but also reached some of the most influential actors in the United States who, like cultural critic Lewis Mumford, were exposed and seduced by the so-called Second Bay Region School and its emphasis on social, political and environ- mental concerns.