Eyes Wide Open

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2018-19

National Crime Agency Annual Report and Accounts 2018-19 HC 2397 National Crime Agency Annual Report and Accounts 2018-19 Annual Report presented to Parliament pursuant to paragraph 8(2) of Schedule 2 to the Crime and Courts Act 2013. Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000. Accounts presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her Majesty. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 22 July 2019. HC 2397 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to National Crime Agency, Command Suite, Unit 1, Spring Gardens, Tinworth Street, London, SE11 5EN. ISBN 978-1-5286-1296-8 CCS0519221654 07/19 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Foreword by the Home Secretary 7 Part Two – Accountability Report Part One – Performance Report Corporate Governance Report 43 Directors’ Report 43 Statement by the Director General 9 Statement of Accounting Officer’s Who we are and what we do 10 responsibilities 44 How -

Serious and Organised Crime Strategy

Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Cm 8715 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of Her Majesty October 2013 Cm 8715 £21.25 © Crown copyright 2013 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www. nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us [email protected] You can download this publication from our website at https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications ISBN: 9780101871525 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2593608 10/13 33233 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Contents Home Secretary Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Introduction 13 Our Strategic Response 25 PURSUE: Prosecuting and disrupting serious and 27 organised crime PREVENT: Preventing people from engaging 45 in serious and organised crime PROTECT: Increasing protection against 53 serious and organised crime PREPARE: Reducing the impact of serious and 65 organised crime Annex A: Accountability, governance and funding 71 Annex B: Departmental roles and responsibilities for 73 tackling serious and organised crime 4 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Home Secretary Foreword 5 Home Secretary Foreword The Relentless Disruption of Organised Criminals Serious and organised crime is a threat to our national security and costs the UK more than £24 billion a year. -

Through a PRISM, Darkly(PDF)

NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Through a PRISM, Darkly Mark Rumold Staff Attorney, EFF NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Electronic Frontier Foundation NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 What we’ll cover today: • Background; what we know; what the problems are; and what we’re doing • Codenames. From Stellar Wind to the President’s Surveillance Program, PRISM to Boundless Informant • Spying Law. A healthy dose of acronyms and numbers. ECPA, FISA and FAA; 215 and 702. NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 the background NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 changes technologytimelaws …yet much has stayed the same NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 The (Way) Background • Established in 1952 • Twin mission: – “Information Assurance” – “Signals Intelligence” • Secrecy: – “No Such Agency” & “Never Say Anything” NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 The (Mid) Background • 1960s and 70s • Cold War and Vietnam • COINTELPRO and Watergate NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 The Church Committee “[The NSA’s] capability at any time could be turned around on the American people and no American would have any privacy left, such is the capability to monitor everything. Telephone conversations, telegrams, it doesn't matter. There would be no place to hide.” Senator Frank Church, 1975 NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Reform • Permanent Congressional oversight committees (SSCI and HPSCI) • Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) – Established requirements for conducting domestic electronic surveillance of US persons – Still given free reign for international communications conducted outside U.S. NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Changing Technology • 1980s - 2000s: build-out of domestic surveillance infrastructure • NSA shifted surveillance focus from satellites to fiber optic cables • BUT: FISA gives greater protection for communications on the wire + surveillance conducted inside the U.S. -

Table of Contents Acknowledgements

The Data Privacy/National Security Balancing Paradigm as Applied In The U.S.A. and Europe: Achieving an Acceptable Balance Paul Raphael Murray, B.A. H.Dip in Ed. LL.B. LL.M Ph.D. (NUI) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy at Trinity College, Dublin School of Law August 2017 Declaration and Online Access I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Paul Raphael Murray Acknowledgements I would like to record my thanks to my Supervisor, Professor Neville Cox, School of Law, and Dean of Graduate Studies, Trinity College, Dublin, for his help and guidance. i ii Abstract The Data Privacy/National Security Balancing Paradigm as Applied In The U.S.A. and Europe: Achieving an Acceptable Balance Paul Raphael Murray The overall research question addressed in this thesis is the data privacy/national security balancing paradigm, and the contrasting ways in which this operates in Europe and the U.S. Within this framework, the influences causing the balance to shift in one direction or another are examined: for example, the terrorist attacks on two U.S. cities in 2001 and in various countries in Europe in the opening decade of the new millennium, and the revelations by Edward Snowden in 2013 of the details of U.S. -

Electronic Security Squadron

6915th ELECTRONIC SECURITY SQUADRON USAFSS turned over Hof Air Station, Germany, to the United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) and inactivated the 6915 SS. 1971 6915th Hof , West Germany (Closed 1971) 6915th ESS Bad Aibling, Ger. 1 Aug '79-30 Sept '93 LINEAGE STATIONS Bad Aibling Station, West Germany ASSIGNMENTS COMMANDERS LTC Arthur R. Marshall HONORS Service Streamers Campaign Streamers Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamers Decorations EMBLEM EMBLEM SIGNIFICANCE MOTTO NICKNAME OPERATIONS The 6915th Electronic Security Squadron is located at Bad Aibling Station, West Germany, in the heart of Bavaria, 35 miles southeast of Munich. The 6915th is a tenant unit, as Bad Aibling Station is "owned" by the Department of Defense. All facets of life on station are joint service. The 6915th enjoys a good relationship with the other services, both on the job and in the community. The mission is a challenging one with electronic equipment that is on the leading edge of technology. All work spaces are new or recently renovated and there are several new facility upgrades projected over the next years. In any workplace except the orderly room, a member's supervisor and coworkers could be Army, Navy, Air Force or civilian, making for a unique and interesting work environment. Although Bad Aibling Station is a small community, 6915th members enjoy a wide range of off duty activities. BAS has the full compliment of sports and leisure facilities with skiing, sight seeing, local German fests and many other outdoor activities offered off-station most of the year. In September 1987, the 6915th hosted their first Air Force Dining-Out. -

A Failure of Intelligence: the Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe

Pace International Law Review Volume 14 Issue 2 Fall 2002 Article 7 September 2002 Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe Kevin J. Lawner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Recommended Citation Kevin J. Lawner, Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe, 14 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 435 (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol14/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-SEPT. 11TH INTERNATIONAL SURVEILLANCE ACTIVITY - A FAILURE OF INTELLIGENCE: THE ECHELON INTERCEPTION SYSTEM & THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO PRIVACY IN EUROPE Kevin J. Lawner* I. Introduction ....................................... 436 II. Communications Intelligence & the United Kingdom - United States Security Agreement ..... 443 A. September 11th - A Failure of Intelligence .... 446 B. The Three Warning Flags ..................... 449 III. The Echelon Interception System .................. 452 A. The Menwith Hill and Bad Aibling Interception Stations .......................... 452 B. Echelon: The Abuse of Power .................. 454 IV. Anti-Terror Measures in the Wake of September 11th ............................................... 456 V. Surveillance Activity and the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe .............................. 460 A. The United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union... 464 B. -

A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers

A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yochai Benkler, A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers, 8 Harv. L. & Pol'y Rev. 281 (2014). Published Version http://www3.law.harvard.edu/journals/hlpr/files/2014/08/ HLP203.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12786017 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers Yochai Benkler* In June 2013 Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Barton Gellman be- gan to publish stories in The Guardian and The Washington Post based on arguably the most significant national security leak in American history.1 By leaking a large cache of classified documents to these reporters, Edward Snowden launched the most extensive public reassessment of surveillance practices by the American security establishment since the mid-1970s.2 Within six months, nineteen bills had been introduced in Congress to sub- stantially reform the National Security Agency’s (“NSA”) bulk collection program and its oversight process;3 a federal judge had held that one of the major disclosed programs violated the -

Utah Data Center, As Well As Any Search Results Pages

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY CENTRAL SECURITY SERVICE FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, MARYLAND 20755-6000 FOIA Case: 84688A 2 May 2017 JOHN GREENEWALD Dear Mr. Greenewald : This responds to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request of 14 June 2016 for Intellipedia pages on Boundless Information and/or BOUNDLESS INFORMANT and/or Bull Run and/or BULLRUN and/or Room 641A and/ or Stellar Wind and/ or Tailored Access Operations and/ or Utah Data Center, as well as any search results pages. A copy of your request is enclosed. As stated in our previous response, dated 15 June 2016, your request was assigned Case Number 84688. For purposes of this request and based on the information you provided in your letter, you are considered an "all other" requester. As such, you are allowed 2 hours of search and the duplication of 100 pages at no cost. There are no assessable fees for this request. Your request has been processed under the FOIA. For your information, NSA provides a service of common concern for the Intelligence Community (IC) by serving as the executive agent for Intelink. As such, NSA provides technical services that enable users to access and share information with peers and stakeholders across the IC and DoD. -

The NSA Is on the Line -- All of Them

The NSA is on the line -- all of them An intelligence expert predicts we'll soon learn that cellphone and Internet companies also cooperated with the National Security Agency to eavesdrop on us. By Kim Zetter, Salon.com May. 15, 2006 | When intelligence historian those safeguards had little effect in preventing Matthew Aid read the USA Today story last at least three telecommunications companies Thursday about how the National Security from repeating history. Agency was collecting millions of phone call records from AT&T, Bell South and Verizon for Aid, who co-edited a book in 2001 on signals a widespread domestic surveillance program intelligence during the Cold War, spent a designed to root out possible terrorist activity in decade conducting more than 300 interviews the United States, he had to wonder whether with former and current NSA employees for his the date on the newspaper wasn't 1976 instead new history of the agency, the first volume of of 2006. which will be published next year. Jeffrey Richelson, a senior fellow at the National Aid, a visiting fellow at George Washington Security Archive, calls Aid the top authority on University's National Security Archive, who has the NSA, alongside author James Bamford. just completed the first book of a three-volume history of the NSA, knew the nation's Aid spoke with Salon about how the NSA has bicentennial marked the year when secrets learned to maneuver around Congress and the surrounding another NSA domestic Department of Justice to get what it wants. He surveillance program, code-named Project compared the agency's current data mining to Shamrock, were exposed. -

Draft Environmnetal Impact Statement for the Green Bank Observatory

Draft November 9, 2017 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Green Bank Observatory, Green Bank, West Virginia National Science Foundation November 9, 2017 Cover Sheet Draft Environmental Impact Statement Green Bank Observatory, Green Bank, West Virginia Responsible Agency: The National Science Foundation (NSF) For more information, contact: Ms. Elizabeth Pentecost Division of Astronomical Sciences Room W9152 2415 Eisenhower Avenue Alexandria, VA 22314 Public Comment Period: November 9, 2017 through January 8, 2018 (extended beyond typical 45-day review period to allow for the holidays) To Submit a Comment: • Send email with subject line “Green Bank Observatory” to: [email protected] • Send mail addressed to: Ms. Elizabeth Pentecost, RE: Green Bank Observatory Division of Astronomical Sciences Room W9152 2415 Eisenhower Avenue Alexandria, VA 22314 Abstract: The NSF has produced a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) to analyze the potential environmental impacts associated with potential funding changes for Green Bank Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia. The five Alternatives analyzed in the DEIS are: A) collaboration with interested parties for continued science- and education-focused operations with reduced NSF funding (the Agency- preferred Alternative); B) collaboration with interested parties for operation as a technology and education park; C) mothballing of facilities; D) demolition and site restoration; and the No-Action Alternative. The environmental resources considered in the DEIS are biological -

Jus Algoritmi: How the NSA Remade Citizenship

Extended Abstract Jus Algoritmi: How the NSA Remade Citizenship John Cheney-Lippold 1 1 University of Michigan / 500 S State St, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States of America / [email protected] Introduction It was the summer of 2013, and two discrete events were making analogous waves. First, Italy’s Minister for Integration, Cécile Kyenge was pushing for a change in the country’s citizenship laws. After a decades-long influx of immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe, the country’s demographic identity had become multicultural. In the face of growing neo-nationalist fascist movements in Europe, Kyenge pushed for a redefinition of Italian citizenship. She asked the state to abandon its practice of jus sanguinis, or citizenship rights by blood, and to adopt a practice of jus soli, or citizenship rights by landed birth. Second, Edward Snowden fled the United States and leaked to journalists hundreds of thousands of classified documents from the National Security Agency regarding its global surveillance and data mining programs. These materials unearthed the classified specifics of how billions of people’s data and personal details were being recorded and processed by an intergovernmental surveillant assemblage. These two moments are connected by more than time. They are both making radical moves in debates around citizenship, though one is obvious while the other remains furtive. In Italy, this debate is heavily ethnicized and racialized. According to jus sanguinis, to be a legitimate part of the Italian body politic is to have Italian blood running in your veins. Italian meant white. Italian meant ethnic- Italian. Italian meant Catholic. -

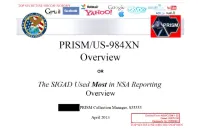

PRISM/US-984XN Overview

TOP SFCRF.T//SI//ORCON//NOFORX a msn Hotmail Go« „ paltalk™n- Youffl facebook Gr-iai! AOL b mail & PRISM/US-984XN Overview OR The SIGAD Used Most in NSA Reporting Overview PRISM Collection Manager, S35333 Derived From: NSA/CSSM 1-52 April 20L-3 Dated: 20070108 Declassify On: 20360901 TOP SECRET//SI// ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEÛEK ® msnV Hotmail ^ paltalk.com Youi Google Ccnmj<K8t« Be>cnö Wxd6 facebook / ^ AU • GM i! AOL mail ty GOOglC ( TS//SI//NF) Introduction ILS. as World's Telecommunications Backbone Much of the world's communications flow through the U.S. • A target's phone call, e-mail or chat will take the cheapest path, not the physically most direct path - you can't always predict the path. • Your target's communications could easily be flowing into and through the U.S. International Internet Regional Bandwidth Capacity in 2011 Source: Telegeographv Research TOP SECRET//SI// ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEQBN Hotmail msn Google ^iïftvgm paltalk™m YouSM) facebook Gm i ¡1 ^ ^ M V^fc i v w*jr ComnuMcatiw Bemm ^mmtmm fcyGooglc AOL & mail  xr^ (TS//SI//NF) FAA702 Operations U « '«PRISM/ -A Two Types of Collection 7 T vv Upstream •Collection of ;ommujai£ations on fiber You Should Use Both PRISM • Collection directly from the servers of these U.S. Service Providers: Microsoft, Yahoo, Google Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube Apple. TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEÛEK Hotmail ® MM msn Google paltalk.com YOUE f^AVi r/irmiVAlfCcmmjotal«f Rhnnl'MirBe>coo WxdS6 GM i! facebook • ty Google AOL & mail Jk (TS//SI//NF) FAA702 Operations V Lfte 5o/7?: PRISM vs.