How the Fallout from Post-9/11 Surveillance Programs Can Inform Privacy Protections for COVID-19 Contact Tracing Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case3:08-Cv-04373-JSW Document174-2 Filed01/10/14 Page1 of 7 Exhibit 2

Case3:08-cv-04373-JSW Document174-2 Filed01/10/14 Page1 of 7 Exhibit 2 Exhibit 2 1/9/14 Case3:08-cv-04373-JSWNew Details S Document174-2how Broader NSA Surveil la n Filed01/10/14ce Reach - WSJ.com Page2 of 7 Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF Order a reprint of this article now format. U.S. NEWS New Details Show Broader NSA Surveillance Reach Programs Cover 75% of Nation's Traffic, Can Snare Emails By SIOBHAN GORMAN and JENNIFER VALENTINO-DEVRIES Updated Aug. 20, 2013 11:31 p.m. ET WASHINGTON—The National Security Agency—which possesses only limited legal authority to spy on U.S. citizens—has built a surveillance network that covers more Americans' Internet communications than officials have publicly disclosed, current and former officials say. The system has the capacity to reach roughly 75% of all U.S. Internet traffic in the hunt for foreign intelligence, including a wide array of communications by foreigners and Americans. In some cases, it retains the written content of emails sent between citizens within the U.S. and also filters domestic phone calls made with Internet technology, these people say. The NSA's filtering, carried out with telecom companies, is designed to look for communications that either originate or end abroad, or are entirely foreign but happen to be passing through the U.S. -

A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers

A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yochai Benkler, A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers, 8 Harv. L. & Pol'y Rev. 281 (2014). Published Version http://www3.law.harvard.edu/journals/hlpr/files/2014/08/ HLP203.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12786017 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers Yochai Benkler* In June 2013 Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Barton Gellman be- gan to publish stories in The Guardian and The Washington Post based on arguably the most significant national security leak in American history.1 By leaking a large cache of classified documents to these reporters, Edward Snowden launched the most extensive public reassessment of surveillance practices by the American security establishment since the mid-1970s.2 Within six months, nineteen bills had been introduced in Congress to sub- stantially reform the National Security Agency’s (“NSA”) bulk collection program and its oversight process;3 a federal judge had held that one of the major disclosed programs violated the -

Meeting the Privacy Movement

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE----- Charset: utf-8 Version: GnuPG v2 hQIMA5xNM/DISSENT7ieVABAQ//YbpD8i8BFVKQfbMy I3z8R8k/ez3oexH+sGE+tPRIVACYMOVEMENTRvU+lSB MY5dvAkknydTOF7xIEnODLSq42eKbrCToDMboT7puJSlWr W Meeting the Privacy Movement d 76hzgkusgTrdDSXure5U9841B64SwBRzzkkpLra4FjR / D z e F Dissent in the Digital Age 0 M 0 0 m BIPhO84h4cCOUNTERREVOLUTION0xm17idq3cF5zS2 GXACTIVISTSXvV3GEsyU6sFmeFXNcZLP7My40pNc SOCIALMOVEMENTgQbplhvjN8i7cEpAI4tFQUPN0dtFmCu h8ZOhP9B4h5Y681c5jr8fHzGNYRDC5IZCDH5uEZtoEBD8 FHUMANRIGHTSwxZvWEJ16pgOghWYoclPDimFCuIC 7K0dxiQrN93RgXi/OEnfPpR5nRU/Qv7PROTESTaV0scT nwuDpMiAGdO/byfCx6SYiSURVEILLANCEFnE+wGGpKA0rh C9Qtag+2qEpzFKU7vGt4TtJAsRc+5VhNSAq8OMmi8 n+i4W54wyKEPtkGREENWALDk41TM9DN6ES7sHtA OfzszqKTgB9y10Bu+yUYNO2d4XY66/ETgjGX3a7OY/vbIh Ynl+MIZd3ak5PRIVACYbNQICGtZAjPOITRAS6E ID4HpDIGITALAGEBhcsAd2PWKKgHARRISON4hN4mo7 LIlcr0t/U27W7ITTIEpVKrt4ieeesji0KOxWFneFpHpnVcK t4wVxfenshwUpTlP4jWE9vaa/52y0xibz6az8M62rD9F/ XLigGR1jBBJdgKSba38zNLUq9GcP6YInk5YSfgBVsvTzb VhZQ7kUU0IRyHdEDgII4hUyD8BERLINmdo/9bO/4s El249ZOAyOWrWHISTLEBLOWINGrQDriYnDcvfIGBL 0q1hORVro0EBDqlPA6MOHchfN+ck74AY8HACKTIVISMy 8PZJLCBIjAJEdJv88UCZoljx/6BrG+nelwt3gCBx4dTg XqYzvOSNOWDENTEahLZtbpAnrot5APPELBAUMzAW Qn6tpHj1NSrAseJ/+qNC74QuXYXrPh9ClrNYN6DNJGQ +u8ma3xfeE+psaiZvYsCRYPTOGRAPHYwkZFimy R9bjwhRq35Fe1wXEU4PNhzO5muDUsiDwDIGITAL A Loes Derks van de Ven X o J 9 1 H 0 w J e E n 2 3 S i k k 3 W Z 5 s XEGHpGBXz3njK/Gq+JYRPB+8D5xV8wI7lXQoBKDGAs -----END PGP MESSAGE----- Meeting the Privacy Movement Dissent in the Digital Age by Loes Derks van de Ven A thesis presented to the -

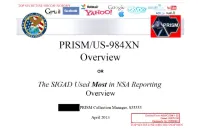

PRISM/US-984XN Overview

TOP SFCRF.T//SI//ORCON//NOFORX a msn Hotmail Go« „ paltalk™n- Youffl facebook Gr-iai! AOL b mail & PRISM/US-984XN Overview OR The SIGAD Used Most in NSA Reporting Overview PRISM Collection Manager, S35333 Derived From: NSA/CSSM 1-52 April 20L-3 Dated: 20070108 Declassify On: 20360901 TOP SECRET//SI// ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEÛEK ® msnV Hotmail ^ paltalk.com Youi Google Ccnmj<K8t« Be>cnö Wxd6 facebook / ^ AU • GM i! AOL mail ty GOOglC ( TS//SI//NF) Introduction ILS. as World's Telecommunications Backbone Much of the world's communications flow through the U.S. • A target's phone call, e-mail or chat will take the cheapest path, not the physically most direct path - you can't always predict the path. • Your target's communications could easily be flowing into and through the U.S. International Internet Regional Bandwidth Capacity in 2011 Source: Telegeographv Research TOP SECRET//SI// ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEQBN Hotmail msn Google ^iïftvgm paltalk™m YouSM) facebook Gm i ¡1 ^ ^ M V^fc i v w*jr ComnuMcatiw Bemm ^mmtmm fcyGooglc AOL & mail  xr^ (TS//SI//NF) FAA702 Operations U « '«PRISM/ -A Two Types of Collection 7 T vv Upstream •Collection of ;ommujai£ations on fiber You Should Use Both PRISM • Collection directly from the servers of these U.S. Service Providers: Microsoft, Yahoo, Google Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube Apple. TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEÛEK Hotmail ® MM msn Google paltalk.com YOUE f^AVi r/irmiVAlfCcmmjotal«f Rhnnl'MirBe>coo WxdS6 GM i! facebook • ty Google AOL & mail Jk (TS//SI//NF) FAA702 Operations V Lfte 5o/7?: PRISM vs. -

SURVEILLE NSA Paper Based on D2.8 Clean JA V5

FP7 – SEC- 2011-284725 SURVEILLE Surveillance: Ethical issues, legal limitations, and efficiency Collaborative Project This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no. 284725 SURVEILLE Paper on Mass Surveillance by the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States of America Extract from SURVEILLE Deliverable D2.8: Update of D2.7 on the basis of input of other partners. Assessment of surveillance technologies and techniques applied in a terrorism prevention scenario. Due date of deliverable: 31.07.2014 Actual submission date: 29.05.2014 Start date of project: 1.2.2012 Duration: 39 months SURVEILLE WorK PacKage number and lead: WP02 Prof. Tom Sorell Author: Michelle Cayford (TU Delft) SURVEILLE: Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Commission Services) Executive summary • SURVEILLE deliverable D2.8 continues the approach pioneered in SURVEILLE deliverable D2.6 for combining technical, legal and ethical assessments for the use of surveillance technology in realistic serious crime scenarios. The new scenario considered is terrorism prevention by means of Internet monitoring, emulating what is known about signals intelligence agencies’ methods of electronic mass surveillance. The technologies featured and assessed are: the use of a cable splitter off a fiber optic backbone; the use of ‘Phantom Viewer’ software; the use of social networking analysis and the use of ‘Finspy’ equipment installed on targeted computers. -

The Criminalization of Whistleblowing

THE CRIMINALIZATION OF WHISTLEBLOWING JESSELYN RADACK & KATHLEEN MCCLELLAN1 INTRODUCTION The year 2009 began a disturbing new trend: the criminalization of whistleblowing. The Obama administration has pursued a quiet but relentless campaign against the news media and their sources. This Article focuses on the sources who, more often than not, are whistleblowers. A spate of “leak” prosecutions brought under the Espionage Act2 has shaken the world of whistleblower attorneys, good- government groups, transparency organizations, and civil liberties advocates. The Obama administration has prosecuted fi ve criminal cases 1. Jesselyn Radack is National Security and Human Rights Director at the Government Accountability Project (GAP), a non-profi t organization dedicated to promoting corporate and government accountability by protecting whistleblowers, advancing occupational free speech, and empowering citizen activists. Kathleen McClellan is National Security and Human Rights Counsel at GAP. 2. Espionage Act of 1917, Pub. L. 65-24, 40 Stat. 217 (June 15, 1917). 57 58 THE LABOR & EMPLOYMENT LAW FORUM [Vol. 2:1 under the Espionage Act, which is more than all other presidential administrations combined.3 These “leak” prosecutions send a chilling message to public servants, as they are contrary to President Barack Obama’s pledge of openness and transparency.4 The vast majority of American citizens do not take issue with the proposition that some things should be kept secret, such as sources and methods, nuclear designs, troop movements, and undercover identities.5 However, the campaign to fl ush out media sources smacks of retaliation and intimidation. The Obama administration is right to protect information that might legitimately undermine national security or put Americans at risk. -

Damming the Leaks: Balancing National Security, Whistleblowing and the Public Interest

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln Memorial University, Duncan School of Law: Digital Commons... LINCOLN MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW _____________________________________ VOLUME 3 FALL 2015 _____________________________________ DAMMING THE LEAKS: BALANCING NATIONAL SECURITY, WHISTLEBLOWING AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST Jason Zenor1 In the last few years we have had a number of infamous national security leaks and prosecutions. Many have argued that these people have done a great service for our nation by revealing the wrongdoings of the defense agencies. However, the law is quite clear- those national security employees who leak classified information are subject to lengthy prison sentences or in some cases, even execution as a traitor. In response to the draconian national security laws, this article proposes a new policy which fosters the free flow of information. First, the article outlines the recent history of national security leaks and the government response to the perpetrators. Next, the article outlines the information policy of the defense industry including the document classification system, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), whistleblower laws and the Espionage Act. Finally, the article outlines a new policy that will advance government transparency by promoting whistleblowing that serves the public interest, while balancing it with government efficiency 1 Assistant Professor, School of Communication, Media and the Arts, State University of New York-Oswego. DAMMING THE LEAKS 62 by encouraging proper channels of dissemination that actually respond to exposures of government mismanagement. “The guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security for our Republic.” Justice Hugo Black2 “The oath of allegiance is not an oath of secrecy [but rather] an oath to the Constitution.” Edward Snowden3 I. -

The Surveillance State and National Security a Senior

University of California, Santa Cruz 32 Years After Orwellian “1984”: The Surveillance State and National Security A Senior Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of BACHELORS OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGY AND LEGAL STUDIES by Ean L. Brown March 2016 Advisor: Professor Hiroshi Fukurai This work is dedicated to my dad Rex along with my family and friends who inspired me to go the extra mile. Special thanks to Francesca Guerra of the Sociology Department, Ryan Coonerty of the Legal Studies Department and Margaret Shannon of Long Beach City College for their additional advising and support. 2 Abstract This paper examines the recent National Security Agency (NSA) document leak by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden and analyzes select programs (i.e. PRISM, Dishfire, and Fairview) to uncover how the agency has maintained social control in the digital era. Such governmental programs, mining domestic data freely from the world’s top technology companies (i.e. Facebook, Google, and Verizon) and listening in on private conversations, ultimately pose a significant threat to the relation of person and government, not to mention social stability as a whole. The paper will also examine the recent government document leak The Drone Papers to detail and conceptualize how NSA surveillance programs are used abroad in Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen. Specifically, this work analyzes how current law is slowly eroding to make room for the ever-increasing surveillance on millions of innocent Americans as well as the changing standard of proof through critical analysis of international law and First and Fourth Amendment Constitutional law. -

SSO Corporate Portfolio Overview

SSO Corporate Portfolio Overview Derived From: NSA/CSSM 1-52 Dated: 20070108 Declassify On: 20361201 What is SSO's Corporate Portfolio? What data can we collect? Where do I go for more help? Agenda 2 What is SSO's Corporate Portfolio? What is SSO Corporate access collection? (TS//SI//NF) Access and collection of telecommunications on cable, switch network, and/or routers made possible by the partnerships involving NSA and commercial telecommunications companies. 3 Brief discussion of global telecommunications infrastructure. How access points in the US can collect on communications from "bad guy" countries (least cost routing, etc.) 4 Unique Aspects Access to massive amounts of data Controlled by variety of legal authorities Most accesses are controlled by partner Tasking delays (TS//SI//NF) Key Points: 1) SSO provides more than 80% of collection for NSA. SSO's Corporate Portfolio represents a large portion of this collection. 2) Because of the partners and access points, the Corporate Portfolio is governed by several different legal authorities (Transit, FAA, FISA, E012333), some of which are extremely time-intensive. 3) Because of partner relations and legal authorities, SSO Corporate sites are often controlled by the partner, who filters the communications before sending to NSA. 4) Because we go through partners and do not typically have direct access to the systems, it can take some time for OCTAVE/UTT/Cadence tasking to be updated at site (anywhere from weekly for some BLARNEY accesses to a few hours for STORMBREW). 5 Explanation of how we can collect on a call between (hypothetically) Iran and Brazil using Transit Authority. -

By Gil Carlson

No longer is there a separation between Earthly technology, other worldly technology, science fiction stories of our past, hopes and aspirations of the future, our dimension and dimensions that were once inaccessible, dreams and nightmares… for it is now all the same! By Gil Carlson (C) Copyright 2016 Gil Carlson Wicked Wolf Press Email: [email protected] To discover the rest of the books in this Blue Planet Project Series: www.blue-planet-project.com/ -1- Air Hopper Robot Grasshopper…7 Aqua Sciences Water from Atmospheric Moisture…8 Avatar Program…9 Biometrics-At-A-Distance…9 Chembot Squishy SquishBot Robots…10 Cormorant Submarine/Sea Launched MPUAV…11 Cortical Modem…12 Cyborg Insect Comm System Planned by DARPA…13 Cyborg Insects with Nuclear-Powered Transponders…14 EATR - Energetically Autonomous Tactical Robot…15 EXACTO Smart Bullet from DARPA…16 Excalibur Program…17 Force Application and Launch (FALCON)…17 Fast Lightweight Autonomy Drones…18 Fast Lightweight Autonomous (FLA) indoor drone…19 Gandalf Project…20 Gremlin Swarm Bots…21 Handheld Fusion Reactors…22 Harnessing Infrastructure for Building Reconnaissance (HIBR) project…24 HELLADS: Lightweight Laser Cannon…25 ICARUS Project…26 InfoChemistry and Self-Folding Origami…27 Iron Curtain Active Protection System…28 ISIS Integrated Is Structure…29 Katana Mono-Wing Rotorcraft Nano Air Vehicle…30 LANdroid WiFi Robots…31 Lava Missiles…32 Legged Squad Support System Monster BigDog Robot…32 LS3 Robot Pack Animal…34 Luke’s Binoculars - A Cognitive Technology Threat Warning…34 Materials -

En En Report

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2009 - 2014 Plenary sitting A7-0139/2014 21.2.2014 REPORT on the US NSA surveillance programme, surveillance bodies in various Member States and their impact on EU citizens’ fundamental rights and on transatlantic cooperation in Justice and Home Affairs (2013/2188(INI)) Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Rapporteur: Claude Moraes RR\1020713EN.doc PE526.085v03-00 EN United in diversityEN PR_INI CONTENTS Page MOTION FOR A EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION.............................................3 EXPLANATORY STATEMENT ............................................................................................45 ANNEX I: LIST OF WORKING DOCUMENTS ...................................................................52 ANNEX II: LIST OF HEARINGS AND EXPERTS...............................................................53 ANNEX III: LIST OF EXPERTS WHO DECLINED PARTICIPATING IN THE LIBE INQUIRY PUBLIC HEARINGS .............................................................................................61 RESULT OF FINAL VOTE IN COMMITTEE.......................................................................63 PE526.085v03-00 2/63 RR\1020713EN.doc EN MOTION FOR A EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION on the US NSA surveillance programme, surveillance bodies in various Member States and their impact on EU citizens’ fundamental rights and on transatlantic cooperation in Justice and Home Affairs (2013/2188(INI)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the Treaty on European Union (TEU), in particular Articles -

SSO FAIRVIEW Overview

TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN SSO FAIRVIEW Overview TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN AGENDA • (U) FAIRVIEW DEFINED • (U) OPERATIONAL AUTHORITIES/CAPABILITIES • (U) STATS: WHO IS USING DATA WE COLLECTED • (U) FAIRVIEW WAY AHEAD AND WHAT IT MEANS FOR YOU • (U) QUESTIONS TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN International Cables (TS//SI//NF) (TS//SI//NF) TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN Brief discussion of global telecommunications infrastructure. How access points in the US can collect on communications from “bad guy” countries (least cost routing, etc.) TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN WHERE SSO IS ACCESSING YOUR TARGET (TS//SI//NF) SSO TARGET UNILATERAL PROGRAMS CABLE MAIL, VOIP, TAP CLOUD SERVICES CORP PARTNER RAM-A RAM-I/X RAM-T RAM-M DGO SSO WINDSTOP BLARNEY SSO CORP MYSTIC AND PRISM FAIRVIEW STORMBREW OAKSTAR TOPI PINWALE XKEYSCORE TURMOIL (TS//SI//NF) TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN FAIRVIEW DEFINED • (TS//SI//NF) Large SSO Program involves NSA and Corporate Partner (Transit, FAA and FISA) • (TS//SI//REL FVEY) Cooperative effort associated witH mid- point collection (cable, switch, router) • (TS//SI//NF) THe partner operates in tHe U.S., but Has access to information tHat transits tHe nation and tHrougH its corporate relationships provide unique accesses to otHer telecoms and ISPs (TS//SI//NF) 5 (TS//SI//NF) TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN Unique Aspects (C) Access to massive amounts of data (C) Controlled by variety of legal authorities (C) Most accesses are controlled by partner (C) Tasking delays TOP SECRET//SI/OC//NOFORN (TS//SI//NF) Key Points: 1) SSO provides more than 80% of collection for NSA.