Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Bugula Neritina (Bryozoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biology Two DOL38 - 41

III. Phylum Platyhelminthes A. General characteristics All About Worms! 1. flat worms a. distinct head & tail ends 2. bilateral symmetry 3. habitat = free-living aquatic or parasitic *a. Parasite = heterotroph that gets its nutrients from the living organisms in/on which they live Ph. Platyhelminthes Ph. Nematoda Ph. Annelida 4. motile 5. carnivores or detritivores 6. reproduce sexually & asexually Biology Two DOL38 - 41 7/4/2016 B. Anatomy 3. Simple nervous system 1. have 3 body layers w/ true tissues a. brain-like ganglia in head & organs b. 2 longitudinal nerves with a. inner = endoderm transverse nerves across body b. middle = mesoderm 4. Lack respiratory, circulatory systems c. outer = ectoderm 5. Parasitic forms lack digestive & excretory systems 2. are acoelomates - lack a coelom around internal organs a. use diffusion to supply needs from host organisms a. digestive tract is formed of endoderm 6. Planaria anat. 7. Tapeworm anat. a. flat body w/ arrow-shaped head & a. head = scolex tapered tail 1) has hooks to help hold onto host b. light-sensitive eyespots on head 2) has suckers to ingest food c. body covered in cilia & mucus to aid b. body segments = proglottids movement 1) new ones form right behind head d. digestive tract only open at mouth 2) each segment produces gametes 1) in center of ventral surface 3) each houses excretory organs 2) used for feeding, excretion C. Physiology 1. Digestion (free-living) a. pharynx extends out of mouth b. sucks food into intestines for digestion c. excretory pores & mouth/pharynx remove wastes 2. Reproduction varies a. Sexual for free-living (& some parasites) 1) hermaphrodites a) cross-fertilize or self-fertilize internally b. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

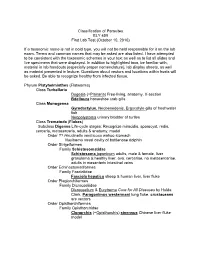

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Kinomes of Selected Parasitic Helminths - Fundamental and Applied Implications

KINOMES OF SELECTED PARASITIC HELMINTHS - FUNDAMENTAL AND APPLIED IMPLICATIONS Andreas Julius Stroehlein BSc (Bingen am Rhein, Germany) MSc (Berlin, Germany) ORCID ID 0000-0001-9432-9816 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2017 Melbourne Veterinary School, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper ii SUMMARY ________________________________________________________________ Worms (helminths) are a large, paraphyletic group of organisms including free-living and parasitic representatives. Among the latter, many species of roundworms (phylum Nematoda) and flatworms (phylum Platyhelminthes) are of major socioeconomic importance worldwide, causing debilitating diseases in humans and livestock. Recent advances in molecular technologies have allowed for the analysis of genomic and transcriptomic data for a range of helminth species. In this context, studying molecular signalling pathways in these species is of particular interest and should help to gain a deeper understanding of the evolution and fundamental biology of parasitism among these species. To this end, the objective of the present thesis was to characterise and curate the protein kinase complements (kinomes) of parasitic worms based on available transcriptomic data and draft genome sequences using a bioinformatic workflow in order to increase our understanding of how kinase signalling regulates fundamental biology and also to gain new insights into the evolution of protein kinases in parasitic worms. In addition, this work also aimed to investigate protein kinases with regard to their potential as useful targets for the development of novel anthelmintic small-molecule agents. This thesis consists of a literature review, four chapters describing original research findings and a general discussion. -

Identifying Monophyletic Groups Within Bugula Sensu Lato (Bryozoa, Buguloidea)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Biblioteca Digital da Produção Intelectual da Universidade de São Paulo (BDPI/USP) Universidade de São Paulo Biblioteca Digital da Produção Intelectual - BDPI Centro de Biologia Marinha - CEBIMar Artigos e Materiais de Revistas Científicas - CEBIMar 2015-05 Identifying monophyletic groups within Bugula sensu lato (Bryozoa, Buguloidea) http://www.producao.usp.br/handle/BDPI/49614 Downloaded from: Biblioteca Digital da Produção Intelectual - BDPI, Universidade de São Paulo Zoologica Scripta Identifying monophyletic groups within Bugula sensu lato (Bryozoa, Buguloidea) KARIN H. FEHLAUER-ALE,JUDITH E. WINSTON,KEVIN J. TILBROOK,KARINE B. NASCIMENTO & LEANDRO M. VIEIRA Submitted: 5 December 2014 Fehlauer-Ale, K.H., Winston, J.E., Tilbrook, K.J., Nascimento, K.B. & Vieira, L.M. (2015). Accepted: 8 January 2015 Identifying monophyletic groups within Bugula sensu lato (Bryozoa, Buguloidea). —Zoologica doi:10.1111/zsc.12103 Scripta, 44, 334–347. Species in the genus Bugula are globally distributed. They are most abundant in tropical and temperate shallow waters, but representatives are found in polar regions. Seven species occur in the Arctic and one in the Antarctic and species are represented in continental shelf or greater depths as well. The main characters used to define the genus include bird’s head pedunculate avicularia, erect colonies, embryos brooded in globular ooecia and branches comprising two or more series of zooids. Skeletal morphology has been the primary source of taxonomic information for many calcified bryozoan groups, including the Buguloidea. Several morphological characters, however, have been suggested to be homoplastic at dis- tinct taxonomic levels, in the light of molecular phylogenies. -

Individual Autozooidal Behaviour and Feeding in Marine Bryozoans

Individual autozooidal behaviour and feeding in marine bryozoans Natalia Nickolaevna Shunatova, Andrew Nickolaevitch Ostrovsky Shunatova NN, Ostrovsky AN. 2001. Individual autozooidal behaviour and feeding in marine SARSIA bryozoans. Sarsia 86:113-142. The article is devoted to individual behaviour of autozooids (mainly connected with feeding and cleaning) in 40 species and subspecies of marine bryozoans from the White Sea and the Barents Sea. We present comparative descriptions of the observations and for the first time describe some of autozooidal activities (e.g. cleaning of the colony surface by a reversal of tentacular ciliature beating, variants of testing-position, and particle capture and rejection). Non-contradictory aspects from the main hypotheses on bryozoan feeding have been used to create a model of feeding mechanism. Flick- ing activity in the absence of previous mechanical contact between tentacle and particle leads to the inference that polypides in some species can detect particles at some distance. The discussion deals with both normal and “spontaneous” reactions, as well as differences and similarities in autozooidal behaviour and their probable causes. Approaches to classification of the diversity of bryozoan behav- iour (functional and morphological) are considered. Behavioural reactions recorded are classified using a morphological approach based on the structure (tentacular ciliature, tentacles and entire polypide) performing the reaction. We suggest that polypide protrusion and retraction might be the basis of the origin of some other individual activities. Individual autozooidal behaviour is considered to be a flexible and sensitive system of reactions in which the activities can be performed in different combinations and successions and can be switched depending on the situation. -

The Transcriptome of Trichuris Suis – First Molecular Insights Into a Parasite with Curative Properties for Key Immune Diseases of Humans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University The Transcriptome of Trichuris suis – First Molecular Insights into a Parasite with Curative Properties for Key Immune Diseases of Humans Cinzia Cantacessi1*, Neil D. Young1, Peter Nejsum2, Aaron R. Jex1, Bronwyn E. Campbell1, Ross S. Hall1, Stig M. Thamsborg2, Jean-Pierre Scheerlinck1,3, Robin B. Gasser1* 1 Department of Veterinary Science, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 2 Departments of Veterinary Disease Biology and Basic Animal and Veterinary Science, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 3 Centre for Animal Biotechnology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia Abstract Background: Iatrogenic infection of humans with Trichuris suis (a parasitic nematode of swine) is being evaluated or promoted as a biological, curative treatment of immune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and ulcerative colitis, in humans. Although it is understood that short-term T. suis infectioninpeoplewithsuchdiseases usually induces a modified Th2-immune response, nothing is known about the molecules in the parasite that induce this response. Methodology/Principal Findings: As a first step toward filling the gaps in our knowledge of the molecular biology of T. suis, we characterised the transcriptome of the adult stage of this nematode employing next-generation sequencing and bioinformatic techniques. A total of ,65,000,000 reads were generated and assembled into -

Unit One Introduction to Marine Invertebrates

Unit One Introduction to Marine Invertebrates Activity 1 - Live Sea Animals . .3 Activity 2- Making an Undersea World . ..6 Objectives: To help students: Touch and identify common beach creatures such as sponges, jellyfishes, anemones, worms, crabs, barnacles, shrimps, amphipods, mollusks, sea stars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers (Activity 1). Understand the meaning of “invertebrate”: a soft-bodied animal without bones (Activity 1). Talk to a diver and/or marine biologist and observe their equipment (Activity 2). Decorate the classroom like an undersea world (Activity 2). Train “animals”(paper bag puppets) for an underwater circus (Activity 2). 1 . -- ., ., -<:.y:: ,.‘. :,” ; . .* . ‘. ..* 7 .*. ‘. ---=j.‘.’ : , ’ . UNIT ONE: Introduction to Marine Invertebrates. The ideal way to approach the study of invertebrates in all their diversity is through observation of live animals. All living things can be classified as belonging to either the plant Activity 1 kingdom orthe animal kingdom. Vertebrates and invertebrates are Live Sea Animals the two major subdivisions of the animal kingdom. Vertebrates are animals with backbones: humans, horses, elephants, mice, fishes, etc. Invertebrates are animals without backbones: sponges, sea stars,insects, worms, jellyfishes. Ninety-five percent of all animal species are invertebrates. There is a great assortment of colors, shapes and sizes among invertebrates found in Alaskan waters. Lacking backbones, they have various ways of supporting their bodies. Some,such as ane- 1 mones, rely on the water itself to give them shape and support. Sponges have a support system of Background: needlelike structures, which form In teaching children about marine entwining mesh. Crabs, an biology, nothing compares in shrimps,and beach hoppers have external skeletons, or “exoskele- excitement and value to the obser- vation of living creatures. -

Colony-Wide Water Currents in Living Bryozoa

COLONY-WIDE WATER CURRENTS IN LIVING BRYOZOA by Patricia L Cook British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Rd., London, SW7 5BD, Gt.Brltain. Résumé Les divers types de courants d'eau des colonies de Bryozoaires sont décrits et analysés. Pour les formes encroûtantes, il en existe au moins trois à l'heure actuelle. Pour les petites colonies de Cyclostomes (Lichenopora), il n'existe qu'un courant centripète se dirigeant vers l'extérieur. Chez certaines Chéilostomes (Hippoporidra) et Cténostomes (Alcyonidium nodosum), des «monticules» sont formés par des groupes de zoïdes dont les couronnes de tentacules sont absentes, réduites ou ne se nourrissent pas. Les « monticules » sont le siège de courants passifs, dirigés vers l'extérieur. Chez d'autres Chéilostomes (Schizoporella, Hippo- porina et Cleidochasma) et des Cténostomates (Flustrellidra hispida), des groupes de zoïdes à couronnes de tentacules hétéromorphes constituent des « cheminées » produisant des courants actifs se dirigeant vers l'extérieur. Des suggestions sont faites concernant une suite d'observations sur les colonies vivantes. Introduction Observation of living colonies is increasingly becoming an essential feature in the study of Bryozoa. Not only is it the primary method of discovering the function of zooids or parts of zooids, it is the first step in testing the established inferences about analogous and homologous structures in preserved material. The study of the functions of whole colonies and the degree and kind of integrative factors contributing to colony-control of these functions is in its early stages. These primary observations can only be made on living colonies. The wide variation in astogeny and ontogeny of structures and their functions in Bryozoa require much further work on many species before any general patterns may become obvious. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Marine Macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 19 An annotated checklist of the marine macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T. Drumm • Katherine P. Maslenikov Robert Van Syoc • James W. Orr • Robert R. Lauth Duane E. Stevenson • Theodore W. Pietsch November 2016 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic Papers NMFS and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientific Editor* Administrator Richard Langton National Marine National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology Economics and Social Analysis Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is pub- lished by the Scientific Publications Of- *Bruce Mundy (PIFSC) was Scientific Editor during the fice, National Marine Fisheries Service, scientific editing and preparation of this report. NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115. The Secretary of Commerce has The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original determined that the publication of research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora and fauna studies, and data- this series is necessary in the transac- intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, engineering, and economics. tion of the public business required by law of this Department. -

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J. R. Finnerty Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “BILATERIA” (=TRIPLOBLASTICA) Bilateral symmetry (?) Mesoderm (triploblasty) Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “COELOMATA” True coelom Coelomata gut cavity endoderm mesoderm coelom ectoderm [note: dorso-ventral inversion] Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA PROTOSTOMIA “first mouth” blastopore contributes to mouth ventral nerve cord The Blastopore ! Forms during gastrulation ectoderm blastocoel blastocoel endoderm gut blastoderm BLASTULA blastopore The Gut “internal, epithelium-lined cavity for the digestion and absorption of food sponges lack a gut simplest gut = blind sac (Cnidaria) blastopore gives rise to dual- function mouth/anus through-guts evolve later Protostome = blastopore contributes to the mouth Deuterostome = blastopore becomes the anus; mouth is a second opening Protostomy blastopore mouth anus Deuterostomy blastopore -

Zoology Lab Manual

General Zoology Lab Supplement Stephen W. Ziser Department of Biology Pinnacle Campus To Accompany the Zoology Lab Manual: Smith, D. G. & M. P. Schenk Exploring Zoology: A Laboratory Guide. Morton Publishing Co. for BIOL 1413 General Zoology 2017.5 Biology 1413 Introductory Zoology – Supplement to Lab Manual; Ziser 2015.12 1 General Zoology Laboratory Exercises 1. Orientation, Lab Safety, Animal Collection . 3 2. Lab Skills & Microscopy . 14 3. Animal Cells & Tissues . 15 4. Animal Organs & Organ Systems . 17 5. Animal Reproduction . 25 6. Animal Development . 27 7. Some Animal-Like Protists . 31 8. The Animal Kingdom . 33 9. Phylum Porifera (Sponges) . 47 10. Phyla Cnidaria (Jellyfish & Corals) & Ctenophora . 49 11. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) . 52 12. Phylum Nematoda (Roundworms) . 56 13. Phyla Rotifera . 59 14. Acanthocephala, Gastrotricha & Nematomorpha . 60 15. Phylum Mollusca (Molluscs) . 67 16. Phyla Brachiopoda & Ectoprocta . 73 17. Phylum Annelida (Segmented Worms) . 74 18. Phyla Sipuncula . 78 19. Phylum Arthropoda (I): Trilobita, Myriopoda . 79 20. Phylum Arthropoda (II): Chelicerata . 81 21. Phylum Arthropods (III): Crustacea . 86 22. Phylum Arthropods (IV): Hexapoda . 90 23. Phyla Onycophora & Tardigrada . 97 24. Phylum Echinodermata (Echinoderms) . .104 25. Phyla Chaetognatha & Hemichordata . 108 26. Phylum Chordata (I): Lower Chordates & Agnatha . 109 27. Phylum Chordata (II): Chondrichthyes & Osteichthyes . 112 28. Phylum Chordata (III): Amphibia . 115 29. Phylum Chordata (IV): Reptilia . 118 30. Phylum Chordata (V): Aves . 121 31. Phylum Chordata (VI): Mammalia . 124 Lab Reports & Assignments Identifying Animal Phyla . 39 Identifying Common Freshwater Invertebrates . 42 Lab Report for Practical #1 . 43 Lab Report for Practical #2 . 62 Identification of Insect Orders . 96 Lab Report for Practical #3 .