Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. X (2006), Pp. 31-57

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces' and Indonesia's

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier To cite this article: Friederike Trotier (2017): The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 Published online: 22 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 Download by: [93.198.244.140] Date: 22 February 2017, At: 10:11 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) often serve as Indonesia; GANEFO; Asian an example of the entanglement of sport, Cold War politics and the games; Southeast Asian Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s. Indonesia as the initiator plays games; International a salient role in the research on this challenge for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Olympic Committee (IOC). The legacy of GANEFO and Indonesia’s further relationship with the IOC, however, has not yet drawn proper academic attention. -

Off the Beaten Track: Women's Sport in Iran, Please Visit Smallmedia.Org.Uk Table of Contents

OFF THE BEATEN TRACK: WOMEn’s SPORT IN IRAN Islamic women’s sport appears to be a contradiction in terms - at least this is what many in the West believe. … In this respect the portrayal of the development and the current situation of women’s sports in Iran is illuminating for a variety of reasons. It demonstrates both the opportunities and the limits of women in a country in which Islam and sport are not contradictions.1 – Gertrud Pfister – As the London 2012 Olympics approached, issues of women athletes from Muslim majority countries were splashed across the headlines. When the Iranian women’s football team was disqualified from an Olympic qualifying match because their hejab did not conform to the uniform code, Small Media began researching the history, structure and representation of women’s sport in Iran. THIS ZINE PROVIDES A glimpsE INto THE sitUatioN OF womEN’S spoRts IN IRAN AND IRANIAN womEN atHLETES. We feature the Iranian sportswomen who competed in the London 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, and explore how the western media addresses the topic of Muslim women athletes. Of course, we had to ground their stories in context, and before exploring the contemporary situation, we give an overview of women’s sport in Iran in the pre- and post- revolution eras. For more information or to purchase additional copies of Off the Beaten Track: Women's Sport in Iran, please visit smallmedia.org.uk TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Historical Background 5 Early Sporting in Iran 6 The Pahlavi Dynasty and Women’s Sport 6 Women’s Sport -

Japan Tohoku Aomori U

Getting to Hirosaki City Sapporo Airplane Hokkaido Chitose Shin-Chitose Airport Tokyo Airport 1hr15min (Haneda) Aomori Airport Nagoya Airport 1hr15min Hirosaki (Komaki) Bus 55min Osaka Airport 1hr35min (Itami) Sapporo Airport 45min (Shin-Chitose) Shin-Hakodate Hokuto Hakodate Airport Shinkansen(JR) J a p a n Hakodate T o h o k u Hayabusa A o m o r i Hokkaido Shinkansen T o k y o Shin-Aomori Minimum 2hr59min Limited Hirosaki H i r o s a k i Express Hayabusa Tsugaru Sendai Minimum 1hr27min Minimum Shin-Hakodate Hayabusa 30min Hokuto Minimum 1hr1min Aomori Hirosaki Railway(JR) Mt. Iwaki Aomori Airport Limited Express Tsugaru Hirosaki Aomori Pref. Hachinohe Shin-Aomori Minimum 35min Lake Towada Limited Express Tsugaru World Heritage Site A k i t a Odate Minimum 2hr Shirakami-Sanchi Hirosaki castle was moved to temporary position for renovating its stonewall. Although visitors can Express Bus Akita Pref. enter the inside of the castle from 2016.4, it will be back to the original position in 2021. Tokyo(Shinagawa The Nocturne Iwate Pref. and Hamamatsu-cho) 9hr15min Akita Iwate Morioka A gateway of World Natural Heritage “Shirakami-sanchi “, T Hirosaki Hirosaki-City is located 60km from Lake Towada and the The Nocturne Japan Sea Hanamaki o Yokohama ho Oirase Gorge. Like Kyoto, Nara, Kanazawa, there was a division 9hr45min Airport k of army, and it did not suffer war damage. Now, both in name Japan Tohoku Aomori u The Castle O and reality, 2,600 the most beautiful cherry blossom trees in S e n d a i S 4hr20min u hi Japan, a castle that is the oldest citadel remains of Japan, L n The Yodel i triple moats, three turrets and five gates are considered as a n M o r i o k a k e 2hr15min a symbol of the city. -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

The Tohoku Traveler Was Created As a Public Service for the Members of the Misawa Community

TOHOKUTOHOKU TRAVELERTRAVELER “.....each day is a journey, and the journey itself home” Basho 1997 TOHOKU TRAVELER STAFF It is important to first acknowledge the members of the Yokota Officers’ Spouses’ Club and anyone else associated with the publication of their original “Travelogue.” Considerable information in Misawa Air Base’s “Tohoku Traveler” is based on that publication. Some of these individuals are: P.W. Edwards Pat Nolan Teresa Negley V.L. Paulson-Cody Diana Hall Edie Leavengood D. Lyell Cheryl Raggia Leda Marshall Melody Hostetler Vicki Collins However, an even amount of credit must also be given to the many volunteers and Misawa Air Base Family Support Flight staff members. Their numerous articles and assistance were instrumental in creating Misawa Air Base’s regionally unique “Tohoku Traveler.” They are: EDITING/COORDINATING STAFF Tohoku Traveler Coordinator Mark Johnson Editors Debra Haas, Dottie Trevelyan, Julie Johnson Layout Staff Laurel Vincent, Sandi Snyder, Mark Johnson Photo Manager/Support Mark Johnson, Cherie Thurlby, Keith Dodson, Amber Jordon Technical Support Brian Orban, Donna Sellers Cover Art Wendy White Computer Specialist Laurel Vincent, Kristen Howell Publisher Family Support Flight, Misawa Air Base, APO AP 96319 Printer U.S. Army Printing and Publication Center, Korea WRITERS Becky Stamper Helen Sudbecks Laurel Vincent Marion Speranzo Debra Haas Lisa Anderson Jennifer Boritski Dottie Trevelyan Corren Van Dyke Julie Johnson Sandra Snyder Mark Johnson Anne Bowers Deborah Wajdowicz Karen Boerman Satoko Duncan James Gibbons Jody Rhone Stacy Hillsgrove Yuriko Thiem Wanda Giles Tom Zabel Hiraku Maita Larry Fuller Joe Johnson Special Note: The Misawa Family Support Flight would like to thank the 35 th Services Squadron’s Travel Time office for allowing the use of material in its “Tohoku Guide” while creating this publication. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition in Modern Japanese Ceramics of the Postwar Period Comparison of a Vase by Hamada Shōji and a Jar by Kitaōji Rosanjin Grant Akiyama Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Grant Akiyama, BS Dr. Hope Marie Childers, Thesis Advisor Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the patience and wisdom of my advisor, Dr. Hope Marie Childers. I thank Dr. Meghen Jones for her insights and expertise; her class on East Asian crafts rekindled my interest in studying Japanese ceramics. Additionally, I am grateful to the entire Division of Art History. I thank Dr. Mary McInnes for the rigorous and unique classroom experience. I thank Dr. Kate Dimitrova for her precision and introduction to art historical methods and theories. I thank Dr. Gerar Edizel for our thought-provoking conversations. I extend gratitude to the libraries at Alfred University and the collections at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum. They were invaluable resources in this research. I thank the Curator of Collections and Director of Research, Susan Kowalczyk, for access to the museum’s collections and records. I thank family and friends for the support and encouragement they provided these past five years at Alfred University. I could not have made it without them. Following the 1950s, Hamada and Rosanjin were pivotal figures in the discourse of American and Japanese ceramics. -

HEART & MATTER: FERMENTATION in a TIME of CRISIS Aaron C

HEART & MATTER: FERMENTATION IN A TIME OF CRISIS Aaron C. Delgaty A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Christopher T. Nelson Margaret J. Wiener Peter Redfield Townsend Middleton Brad Weiss © 2020 Aaron C. Delgaty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron C. Delgaty: Heart & Matter: Fermentation in a Time of Crisis (Under the direction of Christopher T. Nelson) In Heart & Matter, I explore contemporary artisan movements from the perspectives of the artisans that animate these movements, considering how people draw on this emergent category of alternate labor and identity to navigate crises of social, economic, and personal precariousness within the artisan industry. Moving from North Carolina to Okinawa, Tokyo to Chicago, my collaborators shared the quotidian anxiety of how to keep their crafts - and the businesses, livelihoods, and identities tied up in those crafts – relevant, viable, and even successful. Toward survival, my interlocutors engaged in practices of resilience, innovation, and collaboration, elemental threads that wove their working philosophies of craft. At the visceral intersection of ethnography and apprenticeship, I trace a working ethos of emergent artisanship that captures the hopes and anxieties, the successes and failures, the everyday lives and works of craftspeople confronting uncertain frontiers of vocation and taste. By way of introduction, Every Scar a Lesson outlines and demonstrates my primary methodology, an itinerant series of participant observations from the perspective of formal and informal apprenticeship, or what I call a wandering apprenticeship. -

Lacquerware Chemistry

Chemistry the key to our future Lacquerware Sake cup of Wajima-nuri Wajima-nuri 輪島塗Lacquerware The lacquerwares made in Wajima City, Ishikawa Japanese lacquerware is believed to have a history Prefecture are called wajima-nuri, or wajima of around 6800 years, and the oldest lacquerware lacquerware, which is prepared by repeatedly has been excavated in Ishikawa. Some of the covering wood or paper with lacquer. The lacquer reasons why lacquering has flourished around used for such craftworks is sap taken and processed Wajima area may have been that essential materials from Japanese lacquer trees. This natural resin for making lacquerware (tree that provides paint mainly consists of urushiol and may cause lacquer and wood for woodworks as well as good allergy. It also contains a catalyst called laccase, diatomite) were abundantly available, and that there and helps the lacquer to were also active markets thanks to the seaports be oxidized in the air and nearby. polymerize to make a real Here is how a lacquerware is made. Making of a hard coating. The climate wajima-nuri starts with obtaining a quality wooden in Japan, especially in basis. Any fragile parts are reinforced by putting Wajima, provides the desired fabric pieces using lacquer. As primer coating, humidity and temperature for mixture of lacquer and jinoko (powdered diatomite) Sap from urushi tree this polymerization reaction. is applied for more than twice, and raw lacquer is applied to further reinforce breakable points. Then middle and finish coatings of lacquer are applied before various decorative techniques, for example, makie (painting in colored lacquer) or chinkin (sunken gold). -

Nord-Honshū (Tōhoku)

TM Nord-Honshū (Tōhoku) Tōhoku Vorwort Selbst Besuchern, die schon in Japan waren, ist die Region Tōhoku, die den nördlichen Teil der Hauptinsel Honshū umfasst, oft gänzlich unbekannt. Dabei findet man hier all das, was Japan so faszinierend macht, und zudem ohne Besuchermassen. Bis vor kurzem war der Norden Honshūs tatsächlich schwierig zu bereisen – die öffentlichen Verkehrsmittel waren nicht so gut ausgebaut wie im südlichen Teil von Honshū, und auch die englisch- sprachige Ausschilderung ließ noch zu wünschen übrig. Dies alles ist nun im Vorfeld der Olympischen Sommerspiele in Tokio 2020 in Angriff genommen worden. Tōhoku begeistert mit großartigen Landschaften wie den Heiligen Drei Bergen Dewa San- zan in Yamagata, der berühmten Bucht von Matsushima nahe der Stadt Sendai, oder mit der Mondlandschaft um den Vulkan Osorezan. Für kulturell Interessierte bieten die UNESCO Weltkulturerbe-Stätten von Hiraizumi einen Einblick in vergangene Feudalzei- ten. Zahlreiche Feste wie das berühmte Nebuta Matsuri in Aomori oder das Reiter-Festi- val Soma Nomaoi locken jedes Jahr zigtausende Besucher in die Region. FASZINIEREND — BUNT — JAPAN Kurz: es gibt hier Vieles zu entdecken in einer bisher wenig besuchten Region Japans. Das findet inzwischen auch Lonely Planet: für das Jahr 2020 steht Tōhoku an dritter Stelle WIR FLIEGEN SIE HIN! unter den vom Lonely Planet an Top 10 gesetzten Regionen weltweit. Mit diesem Booklet möchten wir Ihren Appetit wecken – schauen Sie selbst, was Tōhoku Ihnen alles zu bieten GOEntdecken Sie Japans viele Facetten und tauchen Sie hat! ein in unvergessliche Erlebnisse. Viel Freude beim Entdecken wünscht Ihnen das JNTO Frankfurt-Team! Erleben Sie Japan bereits bei uns an Bord — 4x täglich und nonstop mit ANA von Deutschland nach Tokio und darüber hinaus. -

HST Catalogue

170 1 LIST – – JAPANESE INTEREST H ANSHAN TANG B OOKS LTD Unit 3, Ashburton Centre 276 Cortis Road London SW 15 3 AY UK Tel (020) 8788 4464 Fax (020) 8780 1565 Int’l (+44 20) [email protected] www.hanshan.com 4 Boehm, Christian: THE CONCEPT OF DANZO. ‘Sandalwood Images’ in Japanese Buddhist Sculpture of the 8th to 14th Centuries. London, 2012. 264 pp. 165 colour and b/w illustrations. 29x21 cm. Boards. £59.95 A detailed study examining Japanese Buddhist sculpture known as Danzo (sandalwood images) and Dangan (portable sandalwood shrines) dating from the 8th to 14th centuries. Includes Chinese examples dating from the 6th to 13th centuries which were imported into Japan and which played a major role in the establishment of the indigenous Japanese danzo tradition. 28 Little, Stephen & Lewis, Edmund J: VIEW OF THE PINNACLE. Japanese Lacquer Writing Boxes: The Lewis Collection of Suzuribako. Honolulu, 2012. xxvii, 228 pp. Colour plates (many full page) throughout. 28x21 cm. Cloth. £80.00 A beautifully-illustrated and well-written study with detailed descriptions of over 80 suzuribako (writing boxes) dating from the 14th to 20th centuries from the fine collection of Edmund and Julia Lewis. Delicious. 31 Metropolitan Museum of Art: DESIGNING NATURE. The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art. New York, 2012. 215 pp. Colour plates throughout. 27x24 cm. Wrappers. £20.00 Catalogue of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York examining the Rinpa (Rimpa) aesthetic in Japanese art, celebrated for its bold rendering of natural motifs, references to literature and poetry and experimentation with calligraphy. -

Medium Specificity and Materiality

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2015 THESIS Dirty Tricks The relevance of skill, expression and authenticity in contemporary clay-based art by Trevor Fry December 2015 STATEMENT This volume is presented as a record of the work undertaken for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF FIGURES .......................................................................................... v SUMMARY.......................................................................................................... ix INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1. THE MAGIC OF CLAY .................................................................................. 9 1.1 Phenomenology and post-structuralism, Edmund de Waal and Rosalind Krauss .......... 19 1.2 De Waal and the magic of clay ........................................................................................ 20 1.3 The deskilled present ....................................................................................................... 30 1.3.1 Urs Fischer’s lumpy spectacles ................................................................................ 33 1.4 Rosalind Krauss ............................................................................................................... 42 1.4.1 Medium specificity .................................................................................................... -

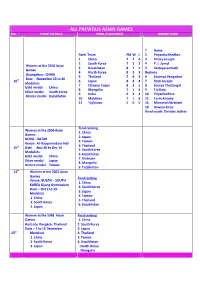

Vb W Previous Ag

ALL PREVIOUS ASIAN GAMES No. EVENT DETAILS FINAL STANDINGS INDIAN TEAM ? Name Rank Team Pld W L 2 Priyanka Khedkar 1 China 7 7 0 3 Princy Joseph 2 South Korea 7 5 2 4 P. J. Jomol Women at the 2010 Asian 3 Kazakhstan 8 7 1 5 Kattuparambath Games 4 North Korea 8 5 3 Reshma Guangzhou - CHINA 5 Thailand 7 4 3 6 Soumya Vengadan Date November 13 to 26 16th 6 Japan 8 4 4 7 Shibi Joseph Medalists 7 Chinese Taipei 8 3 5 8 Soorya Thottangal Gold medal China 8 Mongolia 7 1 6 9 Tiji Raju Silver medal South Korea 9 India 6 2 4 10 Priyanka Bora Bronze medal Kazakhstan 10 Maldives 7 1 6 12 Terin Antony 11 Tajikistan 5 0 5 16 Minomol Abraham 18 Aswani Kiran Head coach: Devidas Jadhav Final ranking Women at the 2006 Asian 1. China Games 2. Japan DOHA - QATAR 3. Taiwan Venue Al-Rayyan Indoor Hall 4. Thailand 15th Date Nov 26 to Dec 14 5. South Korea Medalists 6. Kazakhstan Gold medal China 7. Vietnam Silver medal Japan 8. Mongolia Bronze medal Taiwan 9. Tadjikistan 14th Women at the 2002 Asian Games Final ranking Venue: BUSAN – SOUTH 1. China KOREA Gijang Gymnasium 2. South Korea Date :- Oct 2 to 13 3. Japan Medalists 4. Taiwan 1 China 5. Thailand 2 South Korea 6. Kazakhstan 3 Japan Women at the 1998 Asian Final ranking Games 1. China Host city Bangkok, Thailand 2. South Korea Date :- 7 to 15 December 3. Japan 13th Medalists 4.