The German Theatre Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Premieren Von August Bis Februar*

fotografiert von Ute Mahler und Werner Mahler Die Premieren von August bis Februar* 2014/15 * with English summaries Die Zeit There ist aus den is no Fugen Carolin Emcke und Thomas Ostermeier im Gespräch Wie lässt sich von Krieg und Gewalt erzählen? Gibt es dabei Grenzen des Verstehens? Ist es nicht nur möglich, sondern auch nötig, vom Leid anderer zu erzählen? Diesen Fragen geht Carolin Emcke in ihrem neuesten Buch »Weil es sagbar ist. Über Zeugenschaft und Gerechtigkeit« nach. Ihre Essays sind der Ausgangspunkt für ein Gespräch mit dem Künstlerischen Leiter der Schaubühne, Thomas need Ostermeier, über den Einbruch der Wirklichkeit in die Fiktion, blinde Flecken in Theater und Journa- lismus, tabuisierte gesellschaftliche Konflikte und die Möglichkeit, die Welt erzählend zu verändern. Carolin Emcke ist freie Publizistin und als Reporterin häufig in Krisengebieten unterwegs. Ihre jour- nalistische Arbeit wurde mit zahlreichen Preisen ausgezeichnet. Seit 2004 kuratiert und moderiert sie die monatliche Diskussionsreihe »Streitraum« an der Schaubühne. TO: Bei der Lektüre deines letzten Buches »Weil es am Ende des Stücks mit dem Gift umbringen, an dem bereits sagbar ist«, kamen mir drei Assoziationen in den Sinn. Die Hamlet und seine Mutter und alle anderen gestorben sind. Da erste war das Stück »Zerbombt«. Darin zeigt Sarah Kane eine sagt Hamlet voller Verzweiflung: Du darfst dich nicht umbringen. Paarbeziehung zwischen einem Journalisten und einer jungen Du musst doch meine Geschichte erzählen. Das ist gewisserma- Frau, die offenbar minderjährig ist, noch dazu etwas sprachbe- ßen die einzige Hoffnung, die hier bei Shakespeare bleibt. to be hindert, und von diesem Journalisten missbraucht wird. Damals Das Dritte, was mir einfiel, war »Die Perser« von Aischylos. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Stefka G Mihaylova Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Drama © Copyright 2013 Sarah Guthu University of Washington Abstract European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Thomas E Postlewait School of Drama This dissertation offers a cultural history of the arrival of the second wave of European modernist drama in America in the postwar period, 1950-1970. European modernist drama developed in two qualitatively distinct stages, and these two stages subsequently arrived in the United States in two distinct waves. The first stage of European modernist drama, characterized predominantly by the genres of naturalism and realism, emerged in Europe during the four decades from the 1890s to the 1920s. This first wave of European modernism reached the United States in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, coming to prominence through productions in New York City. The second stage of European modernism dates from 1930 through the 1960s and is characterized predominantly by the absurdist and epic genres. Unlike the first wave, the dramas of the second wave of European modernism were not first produced in New York. Instead, these plays were often given their premieres in smaller cities across the United States: San Francisco, Seattle, Cleveland, Hartford, Boston, and New Haven, in the regional theatres which were rapidly proliferating across the United States. -

Berthold Viertel

Katharina Prager BERTHOLD VIERTEL Eine Biografie der Wiener Moderne 2018 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Veröffentlicht mit der Unterstützug des Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : PUB 459-G28 Open Access: Wo nicht anders festgehalten, ist diese Publikation lizenziert unter der Creative-Com- mons-Lizenz Namensnennung 4.0; siehe http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung : Berthold Viertel auf der Probe, Wien um 1953; © Thomas Kuhnke © 2018 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Korrektorat : Alexander Riha, Wien Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Umschlaggestaltung : Michael Haderer, Wien ISBN 978-3-205-20832-7 Inhalt Ein chronologischer Überblick ....................... 7 Einleitend .................................. 19 1. BERTHOLD VIERTELS RÜCKKEHR IN DIE ÖSTERREICHISCHE MODERNE DURCH EXIL UND REMIGRATION Außerhalb Österreichs – Die Entstehung des autobiografischen Projekts 47 Innerhalb Österreichs – Konfrontationen mit »österreichischen Illusionen« ................................. 75 2. ERINNERUNGSORTE DER WIENER MODERNE Moderne in Wien ............................. 99 Monarchisches Gefühl ........................... 118 Galizien ................................... 129 Jüdisches Wien .............................. -

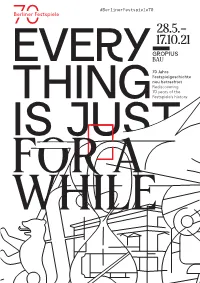

Everything Is Just for a While

#BerlinerFestspiele70 Berliner Festspiele70 28.5.– 17.10.21 GROPIUS BAU EVERY-70 Jahre Festspielgeschichte neu betrachtet Rediscovering 70 years of the THING Festspiele's history IS JUST FOR A WHILE Inhaltsverzeichnis / Table of contents INHALTS- VERZEICHNIS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Vorwort Preface 12 Eine Geschichte der Berliner Festspiele A History of the Berliner Festspiele 40 Videoinstallationen Video installations 54 Filme Films 88 Impressum Imprint Everything Is Just for a While EVERYTHING IS JUST FOR A WHILE 70 Jahre Festspielgeschichte neu betrachtet Rediscovering 70 years of the Festspiele's history Vorwort / Preface Labor und Experiment, Seismograf des Zeitgeist, Ausstellungsort und Debattierklub, Radical Art und Workshops für Jugendliche, Feuer werk und Sport, wochenlang afrikanische Kunst, Städteplanung A laboratory and an experiment, und Autor*innenförderung, Wissen a seismograph of the zeitgeist, an schaftskolleg und Festumzug mit exhibition space and a debating Wasserkorso und immer wieder society, radical art and workshops for Plattform der internationalen Kunst young people, fireworks and sporting szene – all das waren die Berliner events, weeks of African art, urban Festspiele in den vergangenen 70 planning and new writing, an Institute Jahren. Im Geburtstagsjahr zeigt of Advanced Studies and a celebra „Everything Is Just for a While” tory waterborne procession, a recur einen Zusammenschnitt aus rent platform for the international bis lang kaum bekannten Be wegt art scene – over the last 70 years the bildern, ein Spiegelkabinett der Berliner Festspiele have been all of Erin ner ungen. Die Videoinstalla these things. In their birthday year, tionen werden von einer Infowand “Everything Is Just for a While” pre gerahmt, die die Identität und die s ents a compilation of previously Geschichte der Berliner Festspiele littleknown film footage, a hall veranschaulichen. -

Marta Feuchtwanger Papers 0206

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt10003750 No online items Finding Aid for Marta Feuchtwanger papers 0206 Finding aid prepared by Michaela Ullmann USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California 90089-0189 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.usc.edu/locations/special-collections Finding Aid for Marta 02061223 1 Feuchtwanger papers 0206 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Title: Marta Feuchtwanger papers creator: Franklin, Carl M. (Carl Mason) creator: Waldo, Hilde creator: Feuchtwanger, Marta Identifier/Call Number: 0206 Identifier/Call Number: 1223 Physical Description: 98.57 Linear Feet173 boxes Date (inclusive): 1940-1987 Abstract: This archive contains the correspondence of Marta Feuchtwanger, wife of German-Jewish writer Lion Feuchtwanger, who survived her husband by almost thirty years. Marta Feuchtwanger remained an important figure in the exile community and devoted the remainder of her life to promoting the work of her husband. The collection contains Marta Feuchtwanger's personal correspondence, texts and manuscripts by her and others, royalty statements received for the works of her husband, correspondence with publishers, and newspaper clippings mentioning Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger and other exiles. The collection also includes correspondence regarding the establishment and administration of the Feuchtwanger Memorial Library and Villa Aurora. Storage Unit: 91g Storage Unit: 91h Scope and Content This archive contains the correspondence of Marta Feuchtwanger, wife of German-Jewish writer Lion Feuchtwanger, who survived her husband by almost thirty years. Marta Feuchtwanger remained an important figure in the exile community and devoted the remainder of her life after his death to promoting the work of her husband. -

Waldo Frank Papers Ms

Waldo Frank papers Ms. Coll. 823 Finding aid prepared by Donna Brandolisio. Last updated on April 14, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2014 April 30 Waldo Frank papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Administrative Information......................................................................................................................... 10 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 11 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................11 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 16 I. Correspondence.................................................................................................................................. 16 II. Writings...........................................................................................................................................131 -

Witold Gombrowicz Diary of a Playwright

The Polish Review, Vol. 60, No. 2, 2015 © The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Allen J. Kuharski Witold Gombrowicz Diary of a Playwright I am a saint. Yes, I am a saint . and an ascetic. —Witold Gombrowicz, Diary (1967)1 The state of [Witold Gombrowicz’s] oeuvre in 1989 was still imbalanced: in his own words, a “half- cooked steak.” Gombrowicz was certainly known, and above all as a playwright. His plays were staged in the larg- est theaters in Europe. Nevertheless, in most countries (excluding France, Germany, and the Netherlands) only a small part of his work was known, and the most overlooked and poorly- handled text was his Diary. —Rita Gombrowicz, Introduction to Kronos2 Gombrowicz Contra Theater Witold Gombrowicz’s Diary does not fulfill any of the obvious expectations of such a work by a major playwright. Gombrowicz never attended the performance of his works or collaborated in any way with producers, directors, actors, designers, or composers. As a result, there is a complete dearth of theatrical anecdote in the text, though he expresses profound vindication at the positive critical response in Paris and Stockholm to Ivona, Princess of Burgundia. References to other contem- porary playwrights such as Beckett, Brecht, or Weiss are fleeting and superficial. This is a revised version of an article published in Norwegian as “En dramatikers dagbok,” in Witold Gombrowicz: Dagboken 1959–1969 (Oslo: Flamme, Oslo, 2013), ix–xxxii; translated by Ina Vassbotn Steinman. 1. Witold Gombrowicz, Diary, trans. Lillian Vallee (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 714. 2. Rita Gombrowicz, “Na wypadek pożaru,” introduction to Witold Gombrowicz, Kronos (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2013), 12. -

Rev. of <I>Der Rote Hahn</I> by Gerhart Hauptmann, Staged at the Schiller Theater in West Berlin in 1979

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of of Theatre and Film 1980 Rev. of Der rote Hahn by Gerhart Hauptmann, staged at the Schiller Theater in West Berlin in 1979. William Grange University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theatrefacpub Part of the Acting Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Grange, William, "Rev. of Der rote Hahn by Gerhart Hauptmann, staged at the Schiller Theater in West Berlin in 1979." (1980). Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film. 28. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theatrefacpub/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 389 / THEATRE IN REVIEW DER ROTE HAHN. By Gerhart Hauptmann. Parallels to modern German society are here in Schiller Theater, Berlin, West Germany. Novem- abundance, but director Barlog is careful to avoid ber 26, 1979. anything obvious. Inge Meysel as Frau Fielitz, Wilhelm Borchert as von Wehrhahn, Arnfried Ler- Gerhart Hauptmann completed Der rote Hahn inche as Schmarowski, and above all Carl Raddatz as 1901 as a sequel to his highly successful Der Biber- the retarded child's father masterfully create a total pelz (1893), and the two plays share the same neigh- community feeling and simultaneously a feeling that borhood, many of the same characters, and much of the community is breaking up. -

The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany Author(S): Amy C

The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany Author(s): Amy C. Beal Source: American Music, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Winter, 2003), pp. 474-513 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3250575 Accessed: 22/11/2010 15:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=illinois. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Music. http://www.jstor.org AMY C. BEAL The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany Music Most Worthy-At the Office of War Information Even before World War II ended, American composers helped plan for the dissemination of American culture in postwar Europe. -

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain 8 Fairfax Mansions

Vol. XI No. 7 JULY, 1956 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN 8 FAIRFAX MANSIONS. Office ond Consulting Hours: FINCHLEY ROAD (Corner Ftirfix Rotd). Monday to Thursday 10 a.m.— I p.m. 3—6 p.m. LONDON. N.W.3 Friday 10 a.m.— I p.m. Telephone: MAIda Vale 9096/7 (General Office) MAIda Vale 44^9 (Employment Agency and Social Services Dept.) always been in the happy position of giving. Only JEWS FROM GERMANY & HEIRLESS PROPERTY in the most miserable period of their history did they have to tum to their brethren abroad for assistance, which was given with an open hand. A LETTER . Committee, fully met. This should, I think, It was a moral obligation incumbent on the Ger dispose of the suggestion that the CBF uses its man Jews who survived the Nazi catastrophe, to /// our .April issue we expressed our disappoint- share of the JTC funds for its own purposes and repay this debt, and part of the communal pro litem at the refusal by the Jewish Trust Corporation without regard to the needs of former German perty built up by many generations of German UTC) oj an application of the " Council of lews Jews. Jews, together with the unclaimed and heirless from Germany " for an increase from 10 per cent to There is another matter which should be men property, should serve this purpose. That the 12i per cent of its share in the heirless, unclaimed, tioned in Ihis connection. Jewish needs are very funds should also be used to alleviate the plight of and communal property in the former British Zone great and pressing, and the funds allotted by the Jewish Nazi victims from countries other than of Germany. -

‚Gutes' Theater

VS PLUS Zusatzinformationen zu Medien des VS Verlags ‚Gutes’ Theater Theaterfinanzierung und Theaterangebot in Großbritannien und Deutschland im Vergleich 2011 | Erstauflage Anhang Tabellen [Text eingeben] www.viewegteubner.de www.vs -verlag.de Inhaltsverzeichnis Tab. 1: Internationale Definitionen von Kultur, Kultursektor, Kulturindustrien....................................4 Tab. 2: Kulturfinanzierung, GB, 1998/99, in ₤ Mio. und %...................................................................5 Tab. 3: Zentralstaatliche Kulturförderung in GB, 1998/99, in ₤ Mio. und %......................................... 5 Tab. 4: Anteil Kultursponsoring am BIP, D vs. GB, 1999-2007............................................................5 Tab. 5 Production categories , TMA (Beschreibung der Sparten für die Umfrage), ab 1993 ...............6 Tab. 6a: Production categories , SOLT .................................................................................................... 7 Tab. 6b: Sub genres und other production criteria , SOLT ......................................................................7 Tab. 7: Verteilung der deutschen Theater nach Träger, 1990-2005 .......................................................8 Tab. 8: Verteilung Rechtsträger und -formen der deutschen öffentlichen Theaterunternehmen............ 8 Tab. 9: Londoner Theater (SOLT-Mitgliedschaft).................................................................................9 Tab. 10: Wichtigste Londoner Theater, A-Z, Sitzplatzkapazitäten, Eigentümer/ Betreiber..................