CPIN Syria Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 27 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2014 The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process Ken Ifesinachi Ph.D Professor of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Raymond Adibe Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p1154 Abstract The inability of the Syrian government to internally manage the popular uprising in the country have increased international pressure on Syria as well as deepen international efforts to resolve the crisis that has developed into a full scale civil war. It was the need to end the violent conflict in Syria that informed the appointment of Kofi Annan as the U.N-Arab League Special Envoy to Syria on February 23, 2012. This study investigates the U.S and Russian governments’ involvement in the Syrian crisis and the UN Kofi Annan peace process. The two persons’ Zero-sum model of the game theory is used as our framework of analysis. Our findings showed that the divergence on financial and military support by the U.S and Russian governments to the rival parties in the Syrian conflict contradicted the mandate of the U.N Security Council that sanctioned the Annan plan and compromised the ceasefire agreement contained in the plan which resulted in the escalation of violent conflict in Syria during the period the peace deal was supposed to be in effect. The implication of the study is that the success of any U.N brokered peace deal is highly dependent on the ability of its key members to have a consensus, hence, there is need to galvanize a comprehensive international consensus on how to tackle the Syrian crisis that would accommodate all crucial international actors. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

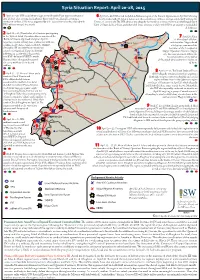

SYR SITREP Map April 20-28 2015

Syria Situation Report: April 20-28, 2015 1 April 24 – 26: ISIS raided three villages in the Shuyukh Plain region southwest of 6 April 22 – 26: ISIS seized the Jabal al-Muhassa region of the Eastern Qalamoun on April 22 following Ayn al-Arab after crossing the Euphrates River with boats, allegedly capturing a heavy clashes with JN, Jaysh al-Islam, and other rebel forces, cutting a strategic rebel supply route in the number of civilians. YPG forces supported by U.S.-led coalition airstrikes clashed with Damascus countryside. e ISIS advance was allegedly facilitated by assistance from local rebel brigade Jaysh ISIS militants to repel the assault. Tahrir al-Sham. Jaysh al-Islam and other rebel forces continue to clash with ISIS in an attempt to retake Jabal al-Muhassa. 2 April 22 – 26: JN and other rebel factions participating in the ‘Jaysh al-Fatah’ Operations Room announced the Qamishli 7 April 26: Ahrar ‘Battle to Liberate Qarmeed Camp’ on April 22 Ayn al-Arab al-Sham, Jaysh al-Islam, targeting a regime military base southeast of Idlib city, 1 Ras al-Ayn and ve other Aleppo-based sparking heavy clashes which included a VBIED rebel groups announced the detonation. JN and rebel forces seized total 7 formation of the ‘Conquest of control over Qarmeed Camp on April 26 Aleppo’ Operations Room in Aleppo following an assault which began with Aleppo Hasakah city. is announcement follows the two BMP-delivered SVBIED attacks. Idlib Sara 4 2 formal dissolution of the Jabhat Regime forces subsequently targeted al-Shamiyah rebel coalition in Aleppo on 11 2 ar-Raqqa the camp with barrel bombs and 2 14 APR. -

Safe Havens in Syria: Missions and Requirements for an Air Campaign

SSP Working Paper July 2012 Safe Havens in Syria: Missions and Requirements for an Air Campaign Brian T. Haggerty Security Studies Program Department of Political Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology [email protected] Copyright © July 15, 2012 by Brian T. Haggerty. This working paper is in draft form and intended for the purposes of discussion and comment. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies are available from the author at [email protected]. Thanks to Noel Anderson, Mark Bell, Christopher Clary, Owen Cote, Col. Phil Haun, USAF, Col. Lance A. Kildron, USAF, Barry Posen, Lt. Col. Karl Schloer, USAF, Sidharth Shah, Josh Itzkowitz Shifrinson, Alec Worsnop and members of MIT’s Strategic Use of Force Working Group for their comments and suggestions. All errors are my own. This is a working draft: comments and suggestions are welcome. Introduction Air power remains the arm of choice for Western policymakers contemplating humanitarian military intervention. Although the early 1990s witnessed ground forces deployed to northern Iraq, Somalia, and Haiti to protect civilians and ensure the provision of humanitarian aid, interveners soon embraced air power for humanitarian contingencies. In Bosnia, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) success in combining air power with local ground forces to coerce the Serbs to the negotiating table at Dayton in 1995 suggested air power could help provide an effective response to humanitarian crises that minimized the risks of armed intervention.1 And though NATO’s -

Observations on the Air War in Syria Lt Col S

Views Observations on the Air War in Syria Lt Col S. Edward Boxx, USAF His face was blackened, his clothes in tatters. He couldn’t talk. He just point- ed to the flames, still about four miles away, then whispered: “Aviones . bombas” (planes . bombs). —Guernica survivor iulio Douhet, Hugh Trenchard, Billy Mitchell, and Henry “Hap” Arnold were some of the greatest airpower theorists in history. Their thoughts have unequivocally formed the basis of G 1 modern airpower. However, their ideas concerning the most effective use of airpower were by no means uniform and congruent in their de- termination of what constituted a vital center with strategic effects. In fact the debate continues to this day, and one may draw on recent con- flicts in the Middle East to make observations on the topic. Specifi- cally, this article examines the actions of one of the world’s largest air forces in a struggle against its own people—namely, the rebels of the Free Syrian Army (FSA). As of early 2013, the current Syrian civil war has resulted in more than 60,000 deaths, 2.5 million internally displaced persons, and in ex- cess of 600,000 refugees in Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon.2 Presi- dent Bashar al-Assad has maintained his position in part because of his ability to control the skies and strike opposition targets—including ci- vilians.3 The tactics of the Al Quwwat al-Jawwiyah al Arabiya as- Souriya (Syrian air force) appear reminiscent of those in the Spanish Civil War, when bombers of the German Condor Legion struck the Basque market town of Guernica, Spain, on 26 April 1937. -

Losing Their Last Refuge: Inside Idlib's Humanitarian Nightmare

Losing Their Last Refuge INSIDE IDLIB’S HUMANITARIAN NIGHTMARE Sahar Atrache FIELD REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2019 Cover Photo: Displaced Syrians are pictured at a camp in Kafr Lusin near the border with Turkey in Idlib province in northwestern Syria. Photo Credit: AAREF WATAD/AFP/Getty Images. Contents 4 Summary and Recommendations 8 Background 9 THE LAST RESORT “Back to the Stone Age:” Living Conditions for Idlib’s IDPs Heightened Vulnerabilities Communal Tensions 17 THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE UNDER DURESS Operational Challenges Idlib’s Complex Context Ankara’s Mixed Role 26 Conclusion SUMMARY As President Bashar al-Assad and his allies retook a large swath of Syrian territory over the last few years, rebel-held Idlib province and its surroundings in northwest Syria became the refuge of last resort for nearly 3 million people. Now the Syrian regime, backed by Russia, has launched a brutal offensive to recapture this last opposition stronghold in what could prove to be one of the bloodiest chapters of the Syrian war. This attack had been forestalled in September 2018 by a deal reached in Sochi, Russia between Russia and Turkey. It stipulated the withdrawal of opposition armed groups, including Hay’at Tahrir as-Sham (HTS)—a former al-Qaeda affiliate—from a 12-mile demilitarized zone along the front lines, and the opening of two major HTS-controlled routes—the M4 and M5 highways that cross Idlib—to traffic and trade. In the event, HTS refused to withdraw and instead reasserted its dominance over much of the northwest. By late April 2019, the Sochi deal had collapsed in the face of the Syrian regime’s military escalation, supported by Russia. -

Aleppo and the State of the Syrian War

Rigged Cars and Barrel Bombs: Aleppo and the State of the Syrian War Middle East Report N°155 | 9 September 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Pivotal Autumn of 2013 ............................................................................................. 2 A. The Strike that Wasn’t ............................................................................................... 2 B. The Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant: from “al-Dowla” to “Daesh” .................... 4 C. The Regime Clears the Way with Barrel Bombs ........................................................ 7 III. Between Hammer and Anvil ............................................................................................ 10 A. The War Against Daesh ............................................................................................. 10 B. The Regime Takes Advantage .................................................................................... 12 C. The Islamic State Bides Its Time ............................................................................... 15 IV. A Shifting Rebel Spectrum, on the Verge of Defeat ........................................................ -

Assessing the French Perspectve on American

ASSESSING THE FRENCH PERSPECTVE ON AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR THROUGH THE 2016 BOMBINGS IN ALEPPO AND FRENCH NEWS MEDIA by KATHERINE GOLAB A THESIS Presented to the Department of Romance Languages and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2020 An Abstract of the Thesis of Katherine Golab for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Romance Languages to be taken June 2020 Title: Assessing the French Perspective on American Involvement in the Syrian Civil War Through the 2016 Bombings in Aleppo and French News Media Approved: Géraldine Poizat-Newcomb, Ph.D. Primary Thesis Advisor As two members of the United Nations’ “Big Five” countries, it is clear that France and the United States of America are both influential global powers. Since America’s independence, the two countries have shared a long and enduring political relationship, which has greatly shaped how each respective culture has influenced the other. Due to their shared history and interdependent power dynamics, current events play an important role in the maintenance of their relationship, which is also heavily present in their shared interests in the Syrian Civil War. This work includes the translation and analysis of 12 articles from four influential French news media organizations to document and explore the French perception of the United States through their news media outlets, in relation to the 2016 attacks on Aleppo. Since both countries have been actively involved in the conflict since its inception, this compilation and analysis sheds light on French-American cooperation, their political connections, and their social relationships. -

Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 25 Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, August, 2012 (Russian Ministry of Defense) Putin's Syrian Gambit Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 25 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2017 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. -

International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Violations in Syria

Helpdesk Report International humanitarian law and human rights violations in Syria Iffat Idris GSDRC, University of Birmingham 5 June 2017 Question Provide a brief overview of the current situation with regard to international humanitarian law and human rights violations in Syria. Contents 1. Overview 2. Syrian government and Russia 3. Armed Syrian opposition (including extremist) groups 4. Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) 5. Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) 6. International coalition 7. References The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk-based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Department for International Development and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of DFID, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Overview All parties involved in the Syrian conflict have carried out extensive violations of international humanitarian law and human rights. In particular, all parties are guilty of targeting civilians. Rape and sexual violence have been widely used as a weapon of war, notably by the government, ISIL1 and extremist groups. The Syrian government and its Russian allies have used indiscriminate weapons, notably barrel bombs and cluster munitions, against civilians, and have deliberately targeted medical facilities and schools, as well as humanitarian personnel and humanitarian objects. -

Control of the Syrian Airspace Russian Geopolitical Ambitions and Air Threat Assessment Can Kasapoğlu

NR. 14 APRIL 2018 Introduction Control of the Syrian Airspace Russian Geopolitical Ambitions and Air Threat Assessment Can Kasapoğlu Russia has mounted its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) footprint in the Levant and also boosted the Syrian Arab Air Defense Force’s capabilities. Syrian skies now remain a heavily contested combat airspace and a dangerous flashpoint. Moreover, there is another grave threat to monitor at low altitudes. Throughout the civil war, various non-state armed groups have acquired advanced man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS), which pose a menacing challenge not only to the deployed forces, but also to commercial aviation around the world. In the face of these threats, NATO needs to draw key lessons-learned from the contemporary Russian opera- tional art, and more importantly, to develop a new understanding in order to grasp the emerging reality in Syria. Simply put, control of the Syrian airspace is becoming an extremely crucial issue, and it will be a determining factor for the war-torn country’s future status quo. Russia’s integrated air defense footprint regard, advanced defensive strategic weapon in Syria was mounted gradually following systems, such as the S-400s and the S-300V4s, its intervention, which began in September were deployed to the Hmeimim Air Base. 2015. That year, the Armed Forces of the This formidable posture was reinforced Russian Federation established the Hmei- by high-end offensive assets, such as SS-26 mim Air Base in the Mediterranean gate- Iskander short-range ballistic missiles and way city of Latakia, adjacent to the Basel Su-35 air superiority fighters. -

The 12Th Annual Report on Human Rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013)

The 12th annual report On human rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013) January 2014 January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Genocide: daily massacres amidst international silence 8 Arbitrary detention and Enforced Disappearances 11 Besiegement: slow-motion genocide 14 Violations committed against health and the health sector 17 The conditions of Syrian refugees 23 The use of internationally prohibited weapons 27 Violations committed against freedom of the press 31 Violations committed against houses of worship 39 The targeting of historical and archaeological sites 44 Legal and legislative amendments 46 References 47 About SHRC 48 The 12th annual report on human rights in Syria (January 2013 – December 2013) Introduction The year 2013 witnessed a continuation of grave and unprecedented violations committed against the Syrian people amidst a similarly shocking and unprecedented silence in the international community since the beginning of the revolution in March 2011. Throughout the year, massacres were committed on almost a daily basis killing more than 40.000 people and injuring 100.000 others at least. In its attacks, the regime used heavy weapons, small arms, cold weapons and even internationally prohibited weapons. The chemical attack on eastern Ghouta is considered a landmark in the violations committed by the regime against civilians; it is also considered a milestone in the international community’s response to human rights violations Throughout the year, massacres in Syria, despite it not being the first attack in which were committed on almost a daily internationally prohibited weapons have been used by the basis killing more than 40.000 regime. The international community’s response to the crime people and injuring 100.000 drew the international public’s attention to the atrocities others at least.