Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies, Vol

Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies, Vol. 6 November 2016 ISSN 2048-0601 © British Association for Chinese Studies Gorbachev’s Glasnost and the Debate on Chinese Socialism among Chinese Sovietologists, 1985-1999 Jie Li University of Edinburgh Abstract Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost (openness) was a popular topic in 1980s China. Existing scholarship remarks that Chinese Soviet-watchers admired Gorbachev’s programme as a model for China’s democratisation in the 1980s. However, after 1991, because of their impact on China’s pro-democracy movement, as perceived by the Chinese government, the same Chinese scholars consistently criticised Gorbachev and his liberalisation policies for being the fundamental catalysts in bringing down the USSR. This paper suggests that the attractiveness of Gorbachev’s glasnost policy to 1980s Chinese Sovietologists was not because it symbolised Western-style democracy; instead, they embraced glasnost as a type of government-led democracy. The impact of Gorbachev’s policies after the mid-1980s can also be seen in Chinese scholars’ use of them to support the reformist General Secretary Zhao Ziyang in his power struggle against the Party conservatives leading up to the Tiananmen Incident. This paper further posits that Chinese scholars’ scorn for Gorbachev after Tiananmen was not primarily owing to his role in promoting democratisation; rather, it was because of Gorbachev’s soft line approach towards dissent when communism in Europe was on the verge of collapse. By drawing attention to Gorbachev’s soft line approach, Chinese critics justified China’s use of the Tiananmen crackdown and the brutal measures adopted by Deng Xiaoping to preserve socialist rule and social stability. -

The Chinese Liberal Camp in Post-June 4Th China

The Chinese Liberal Camp [/) OJ > been a transition to and consolidation of "power elite capital that economic development necessitated further reforms, the in Post-June 4th China ism" (quangui zibenzhuyr), in which the development of the provocative attacks on liberalism by the new left, awareness of cruellest version of capitalism is dominated by the the accelerating pace of globalisation, and the posture of Jiang ~ Communist bureaucracy, leading to phenomenal economic Zemin's leadership in respect to human rights and rule of law, OJ growth on the one hand and endemic corruption, striking as shown by the political report of the Fifteenth Party []_ social inequalities, ecological degeneration, and skilful politi Congress and the signing of the "International Covenant on D... cal oppression on the other. This unexpected outcome has Economic, Social and Cultural Rights" and the "International This paper is aa assessment of Chinese liberal intellectuals in the two decades following June 4th. It provides an disheartened many democracy supporters, who worry that Covenant on Civil and Political Rights."'"' analysis of the intellectual development of Chinese liberal intellectuals; their attitudes toward the party-state, China's transition is "trapped" in a "resilient authoritarian The core of the emerging liberal camp is a group of middle economic reform, and globalisation; their political endeavours; and their contributions to the project of ism" that can be maintained for the foreseeable future. (3) age scholars who can be largely identified as members of the constitutional democracy in China. However, because it has produced unmanageably acute "Cultural Revolution Generation," including Zhu Xueqin, social tensions and new social and political forces that chal Xu Youyu, Qin Hui, He Weifang, Liu junning, Zhang lenge the one-party dictatorship, Market-Leninism is not actu Boshu, Sun Liping, Zhou Qiren, Wang Dingding and iberals in contemporary China understand liberalism end to the healthy trend of politicalliberalisation inspired by ally that resilient. -

Chinese People's Perceptions of and Preparedness for Democracy

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2013 Chinese People's Perceptions of and Preparedness for Democracy Xiangyun Lan Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lan, Xiangyun, "Chinese People's Perceptions of and Preparedness for Democracy" (2013). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2030. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2030 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHINESE PEOPLE'S PERCEPTIONS OF AND PREPAREDNESS FOR DEMOCRACY by Xiangyun Lan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of SCIENCE In Sociology Approved: Peggy Petrzelka Douglas Jackson-Smith Maj or Professor Committee Member Amy K. Bailey Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 20]3 ii Copyright © Xiangyun Lan 2013 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Chinese People's Perceptions of and Preparedness for Democracy by Xiangyun Lan, Master of Science Utah State University, 2013 Major Professor: Dr. Peggy Petrzelka Department: Sociology, Social Work and Anthropology Democratization in China history has always involved exploration and debates on the concept of democracy. This is an ongoing course, continuing currently in China. This - - - thesis seeks to understand Chinese people' s perceptions of democracy and their considerations of the strategies to democratize modem China.l do.so through analyzing a recent widespread internet debate on democracy and democratization stimulated by Han's Three Essays, three blog essays posted by Han Han, an influential public intellectual in China. -

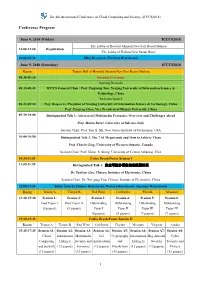

Conference Program

The 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Security (ICCCS2018) Conference Program June 8, 2018 (Friday) ICCCS2018 The Lobby of Howard Johnson New Port Resort Haikou 14:00-21:00 Registration The Lobby of Haikou New Yantai Hotel 18:00-21:30 BBQ Reception (Western Restaurant) June 9, 2018 (Saturday) ICCCS2018 Room Tianjin Hall of Howard Johnson New Port Resort Haikou 08:30-09:10 Opening Ceremony Opening Remarks 08:35-08:45 ICCCS General Chair: Prof. Xingming Sun, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China Welcome Speech 08:45-09:10 Prof. Beiqun Li, President of Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China Prof. Xianfeng Chen, Vice President of Hainan University, China 09:10-10:00 Distinguished Talk 1: Adversarial Multimedia Forensics: Overview and Challenges Ahead Prof. Mauro Barni, University of Salerno, Italy Session Chair: Prof. Yun Q. Shi, New Jersey Institute of Technolgoy, USA 10:00-10:50 Distinguished Talk 2: The 7 AI Megatrends and How to Achieve Them Prof. Charles Ling, University of Western Ontario, Canada Session Chair: Prof. Victor. S. Sheng, University of Central Arkansas, USA 10:50-11:05 Coffee Break/Poster Session I 11:05-11:55 Distinguished Talk 3: 安全可控多模态信息隐藏体系 Dr. Yunbiao Guo, Chinese Institute of Electronics, China Session Chair: Dr. Xin’gang You, Chinese Institute of Electronics, China 12:00-13:30 Buffet Lunch (Chinese Restaurant, Western Restaurant, Japanese Restaurant) Room Tianjin A Tianjin B Red Wine California Florida Missouri 13:30-15:30 Session 1: Session 2: Session -

Download Full Textadobe

JapanFocus http://japanfocus.org/articles/print_article/3285 Charter 08, the Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism Feng Chongyi The publication of Charter 08 in China at the end of 2008 was a major event generating headlines all over the world. It was widely recognized as the Chinese human rights manifesto and a landmark document in China’s quest for democracy. However, if Charter 08 was a clarion call for the new march to democracy in China, its political impact has been disappointing. Its primary drafter Liu Xiaobo, after being kept in police custody over one year, was sentenced on Christmas Day of 2009 to 11 years in prison for the “the crime of inciting subversion of state power”, nor has the Chinese communist party-state taken a single step toward democratisation or improving human rights during the year.1 This article offers a preliminary assessment of Charter 08, with special attention to its connection with liberal forces in China. Liu Xiaobo The Origins of Charter 08 and the Crystallisation of Liberal and Democratic Ideas in China Charter 08 was not a bolt from the blue but the result of careful deliberation and theoretical debate, especially the discourse on liberalism since the late 1990s. In its timing, Charter 08 anticipated that major political change would take place in China in 2009 in light of a number of important anniversaries. These included the 20th anniversary of the June 4th crackdown, the 50th anniversary of the exile of the Dalai Lama, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, and the 90th anniversary of the May 4th Movement. -

A RE-EVALUATION of CHIANG KAISHEK's BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930S

A RE-EVALUATION OF CHIANG KAISHEK’S BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930s A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy DOOEUM CHUNG ProQuest Number: 11015717 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015717 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract Abstract This thesis considers the Chinese Blueshirts organisation from 1932 to 1938 in the context of Chiang Kaishek's attempts to unify and modernise China. It sets out the terms of comparison between the Blueshirts and Fascist organisations in Europe and Japan, indicating where there were similarities and differences of ideology and practice, as well as establishing links between them. It then analyses the reasons for the appeal of Fascist organisations and methods to Chiang Kaishek. Following an examination of global factors, the emergence of the Blueshirts from an internal point of view is considered. As well as assuming many of the characteristics of a Fascist organisation, especially according to the Japanese model and to some extent to the European model, the Blueshirts were in many ways typical of the power-cliques which were already an integral part of Chinese politics. -

The Impact of China's 1989 Tiananmen Massacre

The Impact of China’s 1989 Tiananmen Massacre The 1989 pro-democracy movement in China constituted a huge challenge to the survival of the Chinese communist state, and the efforts of the Chinese Communist party to erase the memory of the massacre testify to its importance. This consisted of six weeks of massive pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing and over 300 other cities, led by students, who in Beijing engaged in a hunger strike which drew wide public support. Their actions provoked repression from the regime, which – after internal debate – decided to suppress the movement with force, leading to a still-unknown number of deaths in Beijing and a period of heightened repression throughout the country. This book assesses the impact of the movement, and of the ensuing repression, on the political evolution of the People’s Republic of China. The book discusses what lessons the leadership learned from the events of 1989, in particular whether these events consolidated authoritarian government or facilitated its adaptation towards a new flexibility which may, in time, lead to the transformation of the regime. It also examines the impact of 1989 on the pro-democracy movement, assessing whether its change of strategy since has consolidated the movement, or if, given the regime’s success in achieving economic growth and raising living standards, it has become increasingly irrelevant. It also examines how the repression of the movement has affected the economic policy of the Party, favoring the development of large State Enterprises and provoking an impressive social polarisation. Finally, Jean-Philippe Béja discusses how the events of 1989 are remembered and have affected China’s international relations and diplomacy; how human rights, law enforcement, policing, and liberal thought have developed over two decades. -

Nationalism in Chinese Foreign Policy: the Case of China's Response to the United States in 1989-2000

Nationalism in Chinese Foreign Policy: the Case of China's Response to the United States in 1989-2000 Junfei Wu London School of Economics and Political Science University of London PhD Thesis UMI Number: U615311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615311 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F « i 2 2 3 qmui Library 0r1B*Ltyaryo<Po*«ca' Economc Soence ,^nel Declaration by Candidate I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been acknowledged. Signature: Date: 2 - ^ \ CCfjSL' Abstract This thesis is concerned with nationalism in Chinese foreign policy. Adopting methods of comparative studies and formalised language analysis, through the case study of China’s response to US engagement, this thesis explores the nationalist momentum in Chinese foreign policy during 1989-2000 and how the CCP loosely controls Chinese IR scholars’ nationalist writings. The thesis argues that China is not a revisionist state despite the rise of the new nationalism. -

The "End of Politics" in Beijing Author(S): Bruce Gilley Source: the China Journal, No

Contemporary China Center, Australian National University The "End of Politics" in Beijing Author(s): Bruce Gilley Source: The China Journal, No. 51 (Jan., 2004), pp. 115-135 Published by: Contemporary China Center, Australian National University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3182149 Accessed: 19/10/2010 00:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ccc. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Contemporary China Center, Australian National University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The China Journal. http://www.jstor.org THE "END OF POLITICS" IN BEIJING* Bruce Gilley The cancellation of the annualleadership retreat at Beidaihe was among the most celebrated acts of Hu Jintao in his first year as General Secretaryof the Chinese Communist Party. -

The Power of Social Media in China: the Government, Websites

The Power of Social Media in China: The Government, Websites and Netizens on Weibo WANG TONG A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Social Sciences in the Department of Political Science, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE ©2012 Acknowledgments “Travel or study, either your body or your soul must be on the way.” Inspired by the motto of my life, two years ago, I decided to take a break from my work in Beijing as a journalist to attend graduate school. For me, the last two years have been a challenging intellectual journey in a foreign country, with many sleepless nights, and solitary days in the library. But I have no regrets for having chosen the difficult path, not least because I have learned a lot from the bittersweet experience. Gradually but surprisingly, I have cultivated an appreciation for the abstract, and have developed a contemplative mind. I believe the value of these hard-acquired skills goes far beyond academic life. I express great respect and gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Zheng Yongnian. Without his patient guidance and advice, I would not have been able to even make a modicum of scholastic achievements. I am particularly thankful to him for encouraging me to freely explore my research topic, for his indefatigable guidance on how to approach academic literature and conceptual framework, and for his immensely useful advice that I should maintain an independent mind when reading. He taught me to think like a scholar and, most importantly, his unparalleled insights into contemporary China studies have deeply influenced me during my thesis writing process. -

Biomolecules

biomolecules Article Comparative Analysis of MicroRNA and mRNA Profiles of Sperm with Different Freeze Tolerance Capacities in Boar (Sus scrofa) and Giant Panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) 1, 2, 1, 1 1 1 Ming-Xia Ran y, Ying-Min Zhou y, Kai Liang y, Wen-Can Wang , Yan Zhang , Ming Zhang , Jian-Dong Yang 1, Guang-Bin Zhou 1 , Kai Wu 2, Cheng-Dong Wang 2, Yan Huang 2, Bo Luo 2, Izhar Hyder Qazi 1,3 , He-Min Zhang 2,* and Chang-Jun Zeng 1,* 1 College of Animal Sciences and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China 2 China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda, Wolong 473000, China 3 Department of Veterinary Anatomy & Histology, Faculty of Bio-Sciences, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Sakrand 67210, Sindh, Pakistan * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.-M.Z.); [email protected] (C.-J.Z.); Tel./Fax: +86-28-86291010 These authors contribute equally to this work. y Received: 21 August 2019; Accepted: 29 August 2019; Published: 1 September 2019 Abstract: Post-thawed sperm quality parameters vary across different species after cryopreservation. To date, the molecular mechanism of sperm cryoinjury, freeze-tolerance and other influential factors are largely unknown. In this study, significantly dysregulated microRNAs (miRNAs) and mRNAs in boar and giant panda sperm with different cryo-resistance capacity were evaluated. From the result of miRNA profile of fresh and frozen-thawed giant panda sperm, a total of 899 mature, novel miRNAs were identified, and 284 miRNAs were found to be significantly dysregulated (195 up-regulated and 89 down-regulated).