Whatever Happened to Red Clydeside? Industrial Conflict and the Politics of Skill in the First World War*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Helen Crawfurd Helen Jack, Born in the Gorbals District

Helen Crawfurd Helen Jack, born in the Gorbals district of Glasgow in 1877, was the third child of William Jack, a Master Baker, and Heather Kyle Jack, of 61 Shore Street, Inverkip. Her father was a member of the Conservative Party and a member of the Presbyterian Church in Scotland. Helen shared her father's religious views and became a Sunday school teacher. Her siblings were William, James, John, Jean and Agnes. In 1898 Helen married Reverend Alexander Montgomerie Crawfurd, and they had one son, Alexander in 1913. His parish was in a slum area of Glasgow and she was deeply shocked by the suffering endured by the working classes. She wrote to a friend about the "appalling misery and poverty of the workers in Glasgow, physically broken down bodies, bowlegged, rickets." Helen Crawfurd also became very interested in the work of Josephine Butler, particularly The Education and Employment of Women. She became convinced that the situation would only change when women had the vote and in 1900 she joined the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), claiming that "if the Mothers of the race had some say, then things would be changed". She held regular meetings in her Glasgow house and took part in protest meetings but she became increasingly frustrated by the lack success of the movement. By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. -

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, the Ytih of DECEMBER, 1947 By

TOnmb, 38161 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the ytih of DECEMBER, 1947 by Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, i JANUARY, 1948 CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS David KIRKWOOD, Esq., J.P., M.P., Member of OF KNIGHTHOOD. Parliament for Dumbarton Burghs since 1922. St. James's Palace, S.W.I. For political and public services. 1st January, 1948. The Honourable William John McKELL, K.C., The KING 'has been graciously pleased to Governor-Gerieral of the Commonwealth of signify His Majesty's intention of conferring Australia. Peerages of the United Kingdom on=> the The Honourable Sir Malcolm Martjin« following:— MACNAGHTEN, K.B.E., lately Judge of the High Court of Justice. To be a Viscount:— George Heaton NICHOLLS, Esq., High Commis- The Righti Honourable John SCOTT, Baron sioner for the Union of South Africa in HYNDLEY, \ G.B.E., Chairman, National London, 1944-1947. Coal Board. Lately Controller-General, The Honourable '• .Sir Humphrey Francis Ministry of Fuel and Power, and Chairman, O'LEARY, K.C.M.G., Chief Justice of New Finance Corporation for Industry, Ltd. Zealand. To be Barons:— Sir Valentine George CRITTALL, J.P. For CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS political and public services. OF KNIGHTHOOD. Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir (William) Sholto DOUGLAS, G.C.B., M.C., D.F.C., St. James's Palace, S.W.I. Comma-nder-in-i&hief and Military Governor, ist January, 1948. Germany, 1946-1947. Sir, Harold Vincent MACKINTOSH, Bt, J.P.; The KING has been graciously pleased to D.L., Chairman, National Savings Com- signify His Majesty's intention of conferring mittee. -

INDEPENDENT LABOUR PARTY REBELS on RED CLYDESIDE Spotlight on Helen Crawfurd & James Maxton in 1910, Keir Hardie, Scottish L

INDEPENDENT LABOUR PARTY REBELS ON RED CLYDESIDE Spotlight on Helen Crawfurd & James Maxton In 1910, Keir Hardie, Scottish leader of the Independent Labour Party (established in 1893) urged a general strike, and especially strikes in the arms and transport industries, should war be declared.1 Outbreak of War When war broke out the Independent Labour Party (ILP) refused to vote in favour of war credits, unlike many of their Parliamentary Labour counterparts.2 Some of the leading campaigners against arms trade profiteering, such as Helen Crawfurd, James Maxton and Philip Snowden, were ILP members. In the second week of war, the ILP published a long resolution unequivocally condemning the belligerent government. It expressed friendship and compassion to workers of all nations: ‘GERMAN WORKERS OUR COMRADES.’ Yet there was no call for protest strikes in the early days of war, despite Hardie’s 1910 resolution.3 Of all the parties represented in Parliament, the ILP took the most anti-militarist stance, yet even it was ambivalent at times. The ILP’s news organ Forward, printed much opposition material under the heading 'Socialist War Points', but it also ran a regular pro-war column by a Clydebank doctor calling himself 'Rob Roy.' With few exceptions, the focus was mostly on capitalist profiteering rather than opposition to the killing industry as such. An example is an article in Forward accusing the government of deliberately starving the state-owned Woolwich Arsenal of work while giving contracts to private firms at higher cost: ‘Great Government Arsenal at Woolwich on Short Time. Profit Plums must be kept for Armament Ring. -

Filenote Enq 2008/5/2-Pcc

FILENOTE ENQ 2008/5/2-PCC 13 October 2008 ‘Fetters and Roses’ Dinner This was an informal name for a dinner given at the House of Commons on 9 January 1924 for Members of Parliament who had been imprisoned for political or religious reasons. This note is intended to assist identification of as many individuals as possible in a photograph which was donated to the Library, through the Librarian, by Deputy Speaker Mrs Sylvia Heal MP. The original of the photograph will be retained by Parliamentary Archives, while scanned copies are accessible online. A report in The Times the following day [page 12] lists 49 people who had accepted invitations. Some of these were current MPs, while others had been Members in the past and at least two [Mrs Ayrton Gould and Eleanor Rathbone] were to become Members in the future. I have counted 46 people in the photograph, not including the photographer, whose identity is unknown. Mr James Scott Duckers [who never became an MP, but stood as a Parliamentary candidate, against Churchill, in a by- election only a few weeks after the dinner] is described on the photograph as being ‘in the chair’. The Times report also points out that ‘it was explained in an advance circular that the necessary qualification is held by 19 members of the House of Commons, of whom 16 were expected to be present at the dinner’. This raises the question of who the absentees were. One possibility might be George Lansbury [then MP for Poplar, Bow & Bromley], who had been imprisoned twice, in 1913 [after a speech in the Albert Hall appeared to sanction the suffragettes’ arson campaign] and in 1921 [he was one of the Poplar councillors who had refused to collect the rates]. -

The Independent Labour Party and Foreign Politics 1918–1923

ROBERT E. DOWSE THE INDEPENDENT LABOUR PARTY AND FOREIGN POLITICS 1918-1923 The Independent Labour Party, which was founded in 1893 had, before the 1914-18 war, played a major part within the Labour Party to which it was an affiliated socialist society. It was the largest of the affiliated socialist societies with a pre-eminently working-class member ship and leadership. Because the Labour Party did not form an individual members section until 1918, the I.L.P. was one of the means by which it was possible to become an individual member of the Labour Party. But the I.L.P. was also extremely important within the Labour Party in other ways. It was the I.L.P. which supplied the leadership - MacDonald, Hardie and Snowden - of both the Labour Party and the Parliamentary Labour Party. It was the I.L.P., with its national network of branches, which carried through a long-term propaganda programme to the British electorate. Finally, it was the I.L.P. which gave most thought to policy and deeply affected the policy of the Labour Party. I.L.P. had, however, no consistent theory of its own on foreign policy before the war; rather the party responded in an ad hoc manner to situations presented to it. What thought there was usually con sisted of the belief that international working class strike action was capable of solving the major questions of war and peace. That the war affected the I.L.P.'s relationship with the Labour Party is well known; the Labour Party formed an individual members section and began to conduct a great deal of propaganda on its own behalf. -

Class Against Class the Communist

CLASS AGAINST CLASS THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF GREAT BRITAIN IN THE THIRD PERIOD, 1927-1932. By Matthew Worley, BA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, August 1998. C TEXT BOUND INTO THE SPINE Acknowledgments This thesis would not have beenpossible without the guidance, encouragementand advice of my supervisorChris Wrigley. Professor Wrigley's encyclopaedicknowledge and ever expanding library madethis project a joy to complete.Closer to home, the loving support and patient encouragementof Louise Aikman kept me focusedand inspired whenever the pressuresof study appearedtoo much to bear. Thanks are also due to Chris, Pete and Simon (for a lifetime's friendship), Scott King (for welcome distractions),Dominic and Andrea (for help and camaraderie), Pete and Kath (for holidays), John (for Manchester),my family (for everything) and Toby Wolfe. ii Contents Abstract iv Abbreviations A Introduction: The Communist Party of Great Britain I in the Third Period Chapter One: A Party in Transition 15 Chapter Two: Towards the Third Period 45 Chapter Three: The New Line 82 Chapter Four: The Party in Crisis 113 Chapter Five: Isolation and Reappraisal 165 Chapter Six: A Communist Culture 206 Chapter Seven: Crisis and Reorganisation 236 Conclusion: The Third Period Reassessed 277 Bibliography 281 iii Abstract This thesis provides an analysisof communismin Britain between 1927 and 1932.In theseyears, the CommunistParty of Great Britain (CPGB) embarkedupon a'new period' of political struggle around the concept of class against class.The increasingly draconianmeasures of the Labour Party and trade union bureaucracybetween 1924 and 1927 significantly restricted the scopeof communist influence within the mainstreamlabour As movement. -

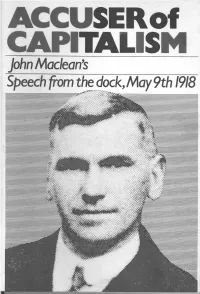

John Maclean's Speech from the Dock, May 9Th 1918 Maclean Cross-Examining a Witness

SM john Maclean's Speech from the dock, May 9th 1918 MacLean cross-examining a witness ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The editor gratefully acknowledges the encouragement of Nan Milton (Maclean); the assistance of staff at the Public Records Office and the National Library of Scotland; and the efforts of many comrades and friends which have made the publication of ACCUSER OF this pamphlet possible. He alone is responsible for the editorial content. CAPITALISM DRAMATIS PERSONAE John Maclean Defendant and 'accuser of capitalism'. Marxist and revolution ary internationalist. Born Pollokshaws, now part of Glasgow, August 24th 1879, of parents evicted from the Scottish Highlands during the 'Clearances'. Second youngest of seven children, three of whom died in infancy. Father died when he was aged eight. Appointed a pupil-teacher, 1896. Graduated from the Free Church Teachers Training College, 1900. Graduated MAin Political Economy from Glasgow University, 1904. Joined Social Democratic Federation (SDF), probably in 1903. Joined Glasgow Teachers' Socialist Society, 1905. Had by then rejected a Calvinistic upbringing for secularism, then atheism, then Marxism. Later described Robert Blatchford's Merrie England as his primary school of socialism, und Marx's Capital as his university. Opposed the sectarianism and jingoism of the SDF leadership, advocating affiliation to the Labour Party and internationalist opposition to war and colonialism. Active in the co-operative movement. Became famous for his public classes in Marxist economics, building some ofthem up to attendances of several hundred. Active in a number of industrial struggles on Clydeside, in Fife, Belfast and elsewhere prior to World War I. Led the internationalist Published by New Pari< Publications, Ltd., wing of the British Socialist Party (formerly the SDF) when 1Q-12 Atlantic Road, London SW9 SHY Printed by Clydeside Press, war was declared in August 1914. -

Finnish Reds and the Origins of British Communism

Articles 29/2 15/3/99 9:52 am Page 179 Kevin Morgan and Tauno Saarela Northern Underground Revisited: Finnish Reds and the Origins of British Communism I The ‘Mystery Man’ On 26 October 1920, a man was arrested leaving the London home of Britain’s first Communist MP. For months detectives had been pursuing this elusive quarry, ‘known to be the principal Bolshevik courier in this country’. He in his turn had taken enormous care to escape their attentions. To contacts at the Workers’ Dreadnought he was known only as Comrade Vie and even his nationality left undisclosed. To others, including Scot- land Yard, he was known variously as Anderson, Carlton, Karlsson and Rubenstein, but also simply as the ‘Mystery Man’. His real name, revealed only after several days’ interrogation, was Erkki Veltheim, a native of Finland.1 The period of Veltheim’s arrest was one of keen if not exag- gerated concern as to the spread into Britain of the virus of Bolshevism.2 The formation of a British Communist Party (CPGB), the holding of a first effective congress of the Communist International (CI) and the rallying of Labour in support of Soviet Russia, all conspired in the summer of 1920 to keep alive such hopes or fears of the coming revolutionary moment. Comrade Vie was not in this respect a reassuring figure. On him were found, as well as military readings and a budget for machine guns, two explosive documents headed ‘Our Work in the Army’ and ‘Advice for British Red Army Officers’. Sinister international associations were betrayed by a coded note on work in Ireland and letters addressed to Lenin and Zinoviev, leaders of the new Soviet state and the Comintern respectively. -

Carrigan, Daniel (2014) Patrick Dollan (1885-1963) and the Labour Movement in Glasgow

Carrigan, Daniel (2014) Patrick Dollan (1885-1963) and the Labour Movement in Glasgow. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5640 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] PATRICK DOLLAN(1885-1963) AND THE LABOUR MOVEMENT IN GLASGOW Daniel Carrigan OBE B.A. Honours (Strathclyde) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2014 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the life and politics of Patrick Dollan a prominent Independent Labour Party (ILP) member and leader in Glasgow. It questions the perception of Dollan as an intolerant, Irish-Catholic 'machine politician' who ruled the 'corrupt' City Labour movement with an 'iron fist', dampened working-class aspirations for socialism, sowed the seeds of disillusionment and stood in opposition to the charismatic left-wing MPs such as James Maxton who were striving to introduce policies that would eradicate unemployment and poverty. Research is also conducted into Dollan's connections with the Irish community and the Catholic church and his attitude towards Communism and communists to see if these issues explain his supposed ideological opposition to left-wing movements. -

The London Gazette, 24 August, 1945

4296 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 24 AUGUST, 1945 WEST RIDING (cont.)— COUNTY OF FORFAR— ' Ripon Division: Major Christopher YORK. Major Simon RAMSAY, M.C. Rather Valley Division: David GRIFFITHS, Esq. COUNTY OF GALLOWAY— Rothwell Division: Thomas Judson BROOKS, John Hamilton M'KiE, Esq. Esq., M.B.E. BURGH OF GLASGOW— Shipley Division: Arthur Creech JONES, Esq. Bridgeton Division: James MAXTON, Esq. Skipton Division: Captain George Burnaby Camlachie Division: Campbell STEPHEN, Esq. DRAY SON. Cathcart Division: Francis BEATTTE, Esq. Sovierby Division: John William BELCHER, Central Division: Lieutenant-Colonel James Esq. Riley Holt HUTCHISON. Spen Valley Division: Lieutenant-Colonel Gorbals Division: George BUCHANAN, Esq. Granville Maynard SHARP. Govan Division: Neil MACLEAN, Esq. Wenlworth Division: Wilfred PALING, Esq. Hillhead Division: The Right Honourable BOROUGH OF YORK— James Scott Cumberland REID, K.C. John CORLETT, Esq. Kelvingrove Division: John Lloyd WILLIAMS, Esq. SCOTLAND. Maryhill Division: William HANNAN, Esq. COUNTY OF ABERDEEN AND KINCARDINE— Partick Division: Arthur Stewart Leslie "Central Division: Harry Reginald SPENCE, YOUNG, Esq. Esq., O.B.E. Pollok Division: Commander Thomas Dunlop Eastern Division: Robert John Graham GALBRAITH. BOOTHBY, Esq. St. Rollox Division: William LEONARD, Esq. Kincardine and Western Division: Colin Shettleston Division: John McGovERN, Esq. Norman THORNTON-KEMSLEY, Esq. Springburn Division: John C. FORMAN, Esq. BURGH OF ABERDEEN— Tradeston Division: John RANKIN, Esq. North Division: Hector Samuel James BURGH OF GREENOCK— HUGHES, Esq., K.C. Hector MCNEIL, Esq. South Division: Sir James Douglas Wishart THOMSON, Bart. COUNTY OF INVERNESS, Ross AND CROMARTY— Inverness Division: Sir Murdoch MACDONALD, COUNTY OF ARGYLL— K.C.M.G. Major Duncan MOCALLUM, M:C, Ross and Cromarty Division: Captain John COUNTY OF AYR AND BUTE— MACLEOD. -

The National Independent Labour Party Affiliation Committee and The

University of Huddersfield Repository Laybourn, Keith and Shepherd, John Labour and Working-Class Lives: Essays to Celebrate the Life and Work of Chris Wrigley Original Citation Laybourn, Keith and Shepherd, John (2017) Labour and Working-Class Lives: Essays to Celebrate the Life and Work of Chris Wrigley. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1784995270 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/31915/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ 7 The disaffiliation crisis of 1932: The Labour Party, the Independent Labour Party and the 1 opinion of ILP members Keith Laybourn On the 9th and 10th of June 1928 the National Administrative Council of the ILP held a closed meeting to discuss its future relations with the Labour Party.