Lessons Learned from China's Wine Producing Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NINGXIA AUTONOMOUS REGION POST EVENT REPORT Introduction

ASIAN WINE – THE SILK ROUTE 2nd Forum and Tasting YINCHUAN – NINGXIA AUTONOMOUS REGION POST EVENT REPORT Introduction 2nd Asian wine Forum-Tasting Baudouin Havaux Replicating Vinopres S.A Chairman - CMB the cultural One of China’s most exciting new wine regions lies in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region in nor- thwest China. Two thousand years ago, Yinchuan lay on the Silk Road, along which goods and ideas interactions travelled between China and Europe: silk went west, and wool, gold, and silver came east. In more recent history, Ningxia was a poverty-stricken coal region whose dusty scrubland was in danger promoted by the of desertification. But, in the nineteen-nineties, the government began to invest seriously in its in- world’s historic frastructure, irrigating immense tracts of desert between the Yellow River and the Helan Mountains. Recently, local officials received a directive to build a “wine route” through the region, similar to Bordeaux’s Route des Vins. trade routes European winegrowers, hired by the government as consultants, had identified Ningxia’s continental climate with dry summers, and plentiful sunlight as ideal for vineyards. However, the region also experiences harsh, freezing winters, making it necessary for winemakers to bury their vines until The BRWSC strikes gold with its second event, hosted by Ningxia spring to protect them from the cold. After a first successful edition in the burgeoning Fangshan region of Beijing in 2016, Vinopres and the Beijing International Wine & Spirit Exchange teamed up this year with representatives from With a strong sense of flair and self-confidence, in less than 20 years, Ningxia has become the heart one of China’s most prominent, and talked-about wine regions – Ningxia – to host the 2018 Belt & of Chinese wine production, with over 100 registered wineries in production. -

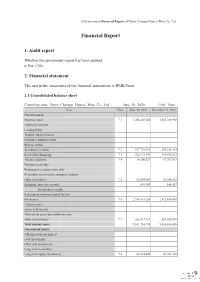

Section 9 Financial Report

2020 SemiannualFinancial Reportt of Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co., Ltd. Financial Report 1. Audit report Whether the semiannual report has been audited □ Yes √ No 2. Financial statement The unit in the statements of the financial annotations is RMB Yuan. 2.1 Consolidated balance sheet Compiling unit: Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co., Ltd. June 30, 2020 Unit: Yuan Item Note June 30, 2020 December 31, 2019 Current assets: Monetary fund 7.1 1,476,207,055 1,565,783,980 Settlement reserves Lending funds Tradable financial assets Derivative financial assets Bills receivable Accounts receivable 7.2 167,738,633 266,218,153 Receivables financing 7.3 222,918,741 316,470,229 Advance payment 7.4 10,200,527 67,707,537 Premium receivable Reinsurance accounts receivable Receivable reserves for reinsurance contract Other receivables 7.5 25,594,801 24,246,812 Including: Interest receivable 698,347 148,927 Dividends receivable Redemptory monetary capital for sale Inventories 7.6 2,936,133,260 2,872,410,407 Contract assets Assets held for sale Non-current assets due within one year Other current assets 7.7 262,917,721 267,424,938 Total current assets 5,101,710,738 5,380,262,056 Non-current assets: Offering loans and imprest Debt investments Other debt investments Long-term receivables Long-term equity investments 7.8 42,810,445 43,981,130 2020 SemiannualFinancial Reportt of Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co., Ltd. Item Note June 30, 2020 December 31, 2019 Other investments in equity instruments Other non-current financial assets Investment real estate 7.9 -

Vineyard Acreage Simulations in Consideration of Climatic Changes Affecting Rhineland-Palatinate (RLP)

38th World Congress of Vine and Wine (Part 1) BIO Web of Conferences Volume 5 (2015) Mainz, Germany 5-10 July 2015 Editor: Jean-Marie Aurand ISBN: 978-1-5108-0746-4 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ You are free to: Share – copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. Adapt – remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. The copyright is retained by the corresponding authors. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2015) For additional information, please contact EDP Sciences – Web of Conferences at the address below. EDP Sciences – Web of Conferences 17, Avenue du Hoggar Parc d'Activité de Courtabœuf BP 112 F-91944 Les Ulis Cedex A France Phone: +33 (0) 1 69 18 75 75 Fax: +33 (0) 1 69 28 84 91 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2634 Email: [email protected] -

Wines That Could Be Appreciable for the Local Consumers

Master’s Degree Programme in Languages, Economics and Institutions of Asia and North Africa (D.M. 270/2004) Final Thesis China Wine Revolution: Is China Becoming a World Wine Power? Supervisor Ch. Prof. Renzo Riccardo Cavalieri Graduand Luca Bonasegale Matriculation Number 866248 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 引⾔ 本论⽂的主题是中国的葡萄酒市场。经过多年相当稳定的经济发展,随着经济的持 续快速增长,中国的葡萄酒市场从20世纪80年代开始发展。多年来,中国⼀直被视为 ⼀个葡萄酒消费国,典型的买家是中产阶级和商⼈,他们主要消费的是瓶⼦精美价格 昂贵的外国葡萄酒。很多时候,购买⾼级葡萄酒只是为了在正式的会议上作为公关的 道具,把精美的瓶装酒作为珍贵的礼物送出,然⽽购买者并不了解葡萄酒⽂化。由于 这些原因,葡萄酒界的许多学者和专业⼈⼠最主要兴趣是从国外⾓度分析这个市场, 以便更好地理解如何允许外国葡萄酒品牌进⼊这个新的市场并开发新的商机。 当然,笔者认为也需要从中国的⾓度来分析市场。中国变化快, ⽽且近⼏年来这个市 场的发展变化如此之⼤,以⾄于称之为“中国葡萄酒⾰命”似乎没有错。中国已不仅仅 是葡萄酒消费国,同时也是世界第六葡萄酒⽣产国。这些变化在许多⽅⾯已经引起了 ⼈们的思考,⽐如对消费者⾏为变化的重新认识。从市场的⾓度来看是这样,在法律 框架内也是如此。因此,这篇论⽂将描述这些重要的变化,并提供有关中国葡萄酒业 ⾛向何处的相关信息,特别关注过去20年来的发展变化。在这场⾰命的发展中,不能 忽视进⼜、外国品牌和⼤多数外国技术援助所具有的重要性。特别要注意的是,在过 去的⼏年⾥,这个市场所⾯临的问题以及中国如何应对。 此研究的⽬的是提供⼀个详尽的讨论,来阐述中国葡萄酒市场怎么发展,并表明它 正在⾛向何⽅,以及中国葡萄酒市场未来将必须⾯对的挑战,以及如果它要成为⼀个 真正的葡萄酒超级⼤国必须采取的对策。 第⼀章将描述中国葡萄酒产业的发展,并分析葡萄酒的特点。葡萄酒在中国已经有 了千年的历史,但在中国消费者中却⼀直存在着相互⽭盾的看法。在过去,葡萄酒是 上层阶级或贵族的利基饮料。在中国⽂化中, ⽩酒等典型的酒精饮料⽐葡萄酒重要。由 于这个原因,可以说,中国酒业刚刚起步于1892,以成渝酒⼚为基础。 !I 多年来,为了提⾼质量,中国在外国专家和伙伴关系的帮助下发展了产业,法国在 这⽅⾯发挥了重要作⽤。因此,中国仿效法国的葡萄酒⽅法,试图⽣产出能为当地消 费者所喜爱的红酒。多年来,中国葡萄酒的最重要榜样是”Cabernet Sauvignon”,⽽其 它⼀般红葡萄酒,主要销往当地市场。随着时代和市场的要求,这⼀做法开始受到批 评,并且根据市场需求,对创新的要求也越来越⾼。 为了更好地理解中国葡萄酒,作者将详细描述这些变化,包括中国葡萄酒的技术特 征、所使⽤的葡萄品种和主要的中国新⽼葡萄种植区。如今,葡萄⼏乎在中国每个省 份都有栽培,但有些省份在葡萄酒市场上有着更为重要的作⽤。由于地中海的⽓候和 附近⼤城市的存在,⼭东省、⼭西省和河北省是最早⽣产葡萄酒的地区。⽆论如何, 随着时间的推移,这些地区已经不如宁夏、新疆和云南等地区受⼈重视。在这些地区, 当地和外国投资正在准备开辟⼀个新的中国葡萄酒天地,⽣产商必须在不同的⽓候和 ⼟壤条件下来种植葡萄。投资和努⼒是伟⼤的,⽽它们的结果今天可以看到。这些葡 -

Development of the Ningxia Wine Industry

BIO Web of Conferences 5, 01021 (2015) DOI: 10.1051/bioconf/20150501021 © Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2015 Toward sustainability: Development of the Ningxia wine industry Linhai Hao, Xueming Li, and Kailong Cao Bureau of Grape Industry Development, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China Abstract. Ningxia government’s key responsibilities for the grape and wine sector are sustainable economic development and natural resource management. While emerging as an industry leader in China, Ningxia has experienced many challenges, the major ones are increasing labor costs and seasonal worker shortages, production cost control, and a market dominated by domes- tic giants and increased imports. Ningxia government made policies to encourage the development of boutique wineries, high quality wines and wine tourism. On natural resource protection, a strict annual irrigation quota has led to the quick adoption of drip irrigation. New vineyards have been designed with a focus on mechanization. Fertilization program will be fine-tuned using the analysis of the soil and the mineral elements in leaves. Various personnel training programs have been organized every year. In summary, the potential of Ningxia wine region has already been proven, and Ningxia government will continually provide its support for the sustainable grape and wine development of the region. 1. Introduction 2. Progress Government support plays a key role in industry develop- The acreage of wine grapes in Ningxia increased from ment in China. For the grape and wine sector, the Ningxia 2.66 thousand ha in 2003 [2] to 6.7 thousand ha in government’s key responsibilities are sustainable economic 2005 [1], and reached 39.3 thousand ha in 2014. -

Redalyc.Research on the Quality of the Wine Grapes in Corridor Area Of

Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos ISSN: 0101-2061 [email protected] Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos Brasil CHENG, Guo; FA, Jie-Qiong; XI, Zhu-Mei; ZHANG, Zhen-Wen Research on the quality of the wine grapes in corridor area of China Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, vol. 35, núm. 1, enero-marzo, 2015, pp. 38-44 Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos Campinas, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=395940120006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative a ISSN 0101-2061 Food Science and Technology DDOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1678-457X.6455 Research on the quality of the wine grapes in corridor area of China Guo CHENG1, Jie-Qiong FA1, Zhu-Mei XI2, Zhen-Wen ZHANG1* Abstract The corridor area of Gansu Province is one of the most important wine grape growing regions in China, and this strip of land results in a significant difference in terms of terroir between its regions. Chemical composition and antioxidant capacity of the main wine grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivated in the corridor area of Gansu Province in northwest China were compared. Three regions (Zhangye, Wuwei, and Jiayuguan) were selected to explain the influence of soil and climate conditions on the quality of wine grapes. This study aims to investigate the effect of different regions on berry composition and antioxidant capacity, providing a general evaluation of red and white wine grapes quality in the corridor area of China. -

Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2015 Annual Report

Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2015 Annual Report Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2015 Annual Report 2016 Final 01 April, 2016 1 Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2015 Annual Report I. Important Notice, Contents and Definition The Board of Directors,the Board of Supervisors,directors, supervisors & senior managers of the Company collectively and individually accept full responsibility for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the information contained in this report and confirm that to the best of their knowledge and belief there are no unfaithful facts, significant omissions or misleading statements. Mr. Sun Liqiang (Chairman of the Company), Mr. Leng Bin (Chief Financial Officer) and Mr. Jiang Jianxun (Financial Director) assure the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial report in the annual report. All directors personally attended the meeting for deliberating the annual report. 1. The Company may face significant risks in production and operation, please refer to “8.expectation for the Company’s future development” sector of “5. Risks likely to occur” part in the chapter four named “Board of Directors’ Report”. We advise investors to read carefully and pay attention to the investment risks. 2. The business plan and target in the report do not represent the earnings forecast of the listed company in 2016, which depends on several factors including the changes of market conditions and the effort extent of managing team etc. with a great uncertainty, so the investors should be in a special attention. The Company’s preliminary scheme of profit distribution deliberated and passed by the board of the directors is as following: “Based on the Company total 685,464,000 shares on 31 December 2015,we plan to pay CNY 5 in cash as dividends for every 10 shares (including tax) to the Company’s all shareholders, send 0 bonus(including tax) and capital reserve will not be transferred to equity. -

When We Arrived at Copower Jade Winery, First Stop of Our Ningxia Visit

When we arrived at Copower Jade winery, first stop of our Ningxia visit, we were only in time to see local farmers picking the last batch of Petit Mangseng for their late-harvest sweet wine. Most vines, in early November, are already buried under the yellow earth. They will hibernate until the next spring. Helan mountain stood quietly afar wearing a snowy cap, overlooking the Loess Plateau under the sandstorm-stained winter sky – exactly as I remembered it two years ago. But everything else is changing fast in this up-and-coming fine wine region in China… Read Jane Anson’s report from 2017: Chinese Pioneers Ningxia geology: Things you may not know The wine planting area occupies the north tip of the Ningxia Autonomous Region, northwest China. Most of its vineyards are found in a narrow strip of land stretching 150km north to south. Viticulture became possible thanks to the Helan Mountain range to the west that provides shelter, and the Yellow River to the east, which serves as a water source. The region is generally steeper, more mountainous on the north and flatter on the south. Alluvial sand and gravel (rock) occupy the lands closer to the mountain, and clay on the plain. Vines waiting to be buried at Chateau Changyu Moser XV, with Helan Mountain as the backdrop. Ningxia has a reputation for its plentiful sunshine – over 3100 hours of sunshine and over 200 frost-free days per year, according to statistics from the Ningxia wine bureau – or the ‘Administrative Committee of the Grape Industry Zone of Helan Mountain East Foothills’. -

Download Transcript

Ep 50 Wines of Ningxia, China with Winemaker Lenz Moser of C... Sun, 5/23 10:57AM 1:06:39 SUMMARY KEYWORDS ningxia, wine, china, winemaking, wines, vineyards, cabernet sauvignon, chateau, austria, winemaker, absolutely, tannins, bit, people, cabernet, years, winery, vintage, moser, mondavi SPEAKERS Janina Doyle, Lenz Moser J Janina Doyle 00:07 Welcome to Eat Sleep Wine Repeat, a podcast for all you wine lovers, who, if you're like me just cannot get enough of the good stuff. I'm Janina Doyle, your host, Brand Ambassador, Wine Educator, and Sommelier. So stick with me as we dive deeper into this ever evolving wonderful world of wine. And wherever you are listening to this, cheers to you. Ep 50 Wines of Ningxia, China with WinemPaakgeer L1e onfz 3 M2oser of C... Transcribed by https://otter.ai J Janina Doyle 00:31 Hello to you all. So this episode is a slightly longer one, but it will be worth it because I am chatting with Austrian winemaking extraordinaire Lenz Moser. You will learn a little bit about how he and his winemaking father and grandfather changed the Austrian winemaking landscape. But the big focus is on China. Welcome to the wonderful growing world of Chinese wine. We're going to focus mainly on Ningxia, which is where his winery is, but you'll learn a little bit more about the other regions, vintages, the terroir of this region, how it's advancing. So much to learn about, and we're gonna be tasting some of the delicious wines of Chateau Changyu Moser XV as we go along. -

The 37Th World Congress of Vine and Wine, "Southern

The 37th World Congress of Vine and Wine, "Southern Vitiviniculture, a Confluence of Knowledge and Nature Mendoza, Argentina 9th to 14th November 2014 PROGRAMA CIENTÍFICO SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM PROGRAMME SCIENTIFIQUE PROGRAMA SCIENTIFICO WISSENSCHAFTLICHES PROGRAMM MONDAY 10th November TUESDAY 11th November WEDNESDAY 12th November 9:00 2014-770 The 9:00 2014-741 Construction of 9:00 2014-367 Alignment of 9:00 2014-561 Impact of 9:00 2014-312 Investigating 9:00 2014-590 Wine and preservation of genetic low-ethanol producing interests and actions as a climate change on some intramolecular isotopic tourism sectors: looking resources of the vine yeasts though partial success factor for German grapevine varieties grown inhomogeneities of for synergies requires cohabitation deletions and base pair wine cooperatives? for pisco production in organic oxy acids to reveal between institutional substitutions of the Peru adulterated wines and clonal selection, mass Saccharomyces cerevisiae juice-containing beverages selection and private PDC2 gene clonal selection 9:10 2014-282 Wine Analysis To Check Quality And Authenticity By Full- Automated 1H-NMR 9:20 2014-305 A Research on 9:20 2014-751 Genetic 9:20 2014-481 The entry of 9:20 2014-764 Increased 9:20 2014-451 The nursery the Affinity Coefficients of screening of mutant LSP into the Wine Industry temperature, water stress production: an instrument Red Globe Grape Variety Dekkera Bruxellensis Supply Chain and abscisic acid on the to evaluate the evolution with 140 R, 41 B strains with low- composition of of viticulture Rootstocks in 2012 and ethylphenol production winemaking wines Vitis 2013 Year 9:30 2014-555 Market Power in vinifera cv. -

Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2016 Semi-Annual Report

Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2016 Semi-annual Report Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2016 Semi-annual Report 2016-Final 03 August 2016 1 Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2016 Semi-annual Report Contents I、Important Notice, Contents and Definition................................................................................3 II、Brief Introduction for the Company ....................................................................................... 5 III、Summary of Accounting Data and Financial Indicators ......................................................7 IV、Board of Directors’ Report ....................................................................................................10 V、Major Issues ............................................................................................................................. 22 VI、Changes in Shares and the Shareholders’ Situation ........................................................... 31 VII、Relative situation for preferred shares.................................................................................35 VIII、Situation for Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management ............................................. 36 IX、Financial Report .....................................................................................................................37 X、Catalogue of Documents for Future Reference.....................................................................130 2 Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co. Ltd. 2016 Semi-annual Report I. Important Notice, Contents -

That Ningxia Style

REGIONAL ANALYSIS CHINA THAT NINGXIA STYLE Austrian wine entrepreneur Lenz M. Moser headed to China more than a decade ago, wanting to see what was going on. Now, he can’t stay away. Here he gives his impressions 5/15 MEININGER’S WBI 5/15 MEININGER’S of the Ningxia wine region. Chateau Changyu Moser XV, Ningxia come from a family of winemakers who have Carménère grapes from France – now known Ancient civilisation been making wine in Niederösterreich, in China as Cabernet Gernischt. IAustria for 15 generations. My grandfather, Although it can take a long time to build To understand the region – in the heart Professor Dr Lorenz Moser III, in the 1920s relationships, you build them for life. In 2013, of Asia, south of Mongolia – it helps to becamse the first ever winegrower to put Changyu built a new chateau in Ningxia. understand some history. Ningxia was part of vineyards on trellises, and my father started They spent $79m on it, including a museum the Western Xia (or the Xia-Xia Dynasty) from the Lenz Moser Winery where I worked as and massive barrel hall – and then named the eleventh to thirteenth centuries and was managing director for many years. I created it Chateau Changyu Moser XV. On our side, repeatedly invaded by the Mongols. Yet it also TxB International with partners with a fine we’ve helped Changyu create wines that benefited economically from being one of the wine portfolio. TxB has super-premium wines have a more European profile, and have been main trading centres along the ancient silk such as Michael Mondavi Family Wines, but instrumental in getting them into European road, which gave it the wealth to develop great it also creates fine wine brands from new and distribution.